Abstract

This study analyses the influence of environmental and individual conditions on the quality and the speed of entrepreneurial re-entries in emerging economies after a business failure. We propose a conceptual framework supported by the institutional economic theory to study the influence of environmental conditions; and human and social capital to study the influence of individuals’ skills, experiences, and relationships. A retrospective multiple case study analysis was designed to test our conceptual model by capturing longitudinal information on occurred events, trajectory, and determinants of twenty re-entrepreneurs. Our results show that the entrepreneurial experience and type of venture influence the accelerating effect of re-entrepreneurship, as well as how environmental conditions moderate the quality and speed of entrepreneurial re-entries. We provoke a discussion and implications for multiple actors involved in the re-entry of entrepreneurs after a business failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a dynamic process that implies the conception, gestation, childhood, adolescence as well as the death of an entrepreneurial initiative (DeTienne 2010; Shepherd et al. 2019). Previous studies have recognised how individual, organisational, and contextual conditions determine the transition across all stages of the dynamic entrepreneurial process (McMullen and Shepherd 2006). An inadequate combination of these conditions will produce a business exit or failure (Kang and Uhlenbruck 2006; Khelil 2016; Mellahi and Wilkinson 2004). Although the business exit/failure literature continues to expand, the speed and the quality entrepreneurial re-entry after a business failure still requires conceptual and empirical debates (Fu et al. 2018; Hsu et al. 2017a; Ucbasaran et al. 2013) in both developing and emerging economies (Amankwah-Amoah 2018; Koçak et al. 2010; Ravindran and Baral 2014).

On the one hand, the first debate is about the role of context in entrepreneurial re-entries. Although entrepreneurship studies have recognised that context matters, a few studies have analysed how contextual conditions affect entrepreneurial re-entries (Fu et al. 2018, p. 466). As with any entrepreneurial activity, institutional conditions will determine the quality and quantity of new entrepreneurship re-entries, especially in emerging economies (Acs et al. 2017; Cardon et al. 2011; Mason and Brown 2013, 2014; Simmons et al. 2018; Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019; Lin and Wang 2019). Entrepreneurship ecosystems have become a popular topic of discussion among scholars and policymakers (Guerrero and Urbano 2017).

On the other hand, the second debate is associated with the role of individual human and social capitals on entrepreneurial re-entries. Although prior studies have made significant contributions to the individual characteristics, few studies provide insights about a positive impact of learning after failure in entrepreneurial re-entries (Cope 2011; p. 605). Based on learning and error mastery orientation (Funken et al. 2018), business failure produces positive/negative learning outcomes that influence entrepreneurial preparedness for future re-entry (Neumeyer et al. 2019; Nielsen and Sarasvathy 2011; Shepherd et al. 2019; Surdu et al. 2018). Re-entrepreneurs gain entrepreneurial experience and build relationships with different agents in the ecosystem and intermediaries to reduce institutional voids (Lee et al. 2011; Mair et al. 2012).

Inspired by these academic debates, this study analyses the influence of environmental and individual conditions on the quality and the speed of entrepreneurial re-entries in emerging economies after a business failure. By adopting the foundations of the institutional economics approach (North 1990), we examine the role of entrepreneurial ecosystem pillars (formal conditions) and societal perceptions of entrepreneurship (informal conditions) on the speed/quality of an entrepreneurial re-entry trajectory after failure in emerging economies. By adopting the theoretical foundations of human capital (Becker 1993) and social capital (Baron and Markman 2000), we examine the role of the individuals’ skills, experience and knowledge (human capital) and the individuals’ relationships with close people or networks (social capital) on the speed/quality of an entrepreneurial re-entry trajectory after failure in emerging economies. Based on these approaches, we proposed a conceptual framework and several propositions that were analysed using a retrospective case study approach of twenty Chilean re-entrepreneurs.

After this introduction, we first present the theoretical background about the determinants of the entrepreneurial re-entry after failure and offer propositions about the quality and speed of re-entries. We later introduce our methodological design. We then describe and analyse our findings. Finally, we offer a concluding discussion focused on the implications of our model for future research and practice.

Determinants of the quality and speed of entrepreneurial re-entries into emerging economies

Business failure, entrepreneurial re-entry and emerging economies

To analyse the trajectory of entrepreneurial re-entries, in emerging economies, it is crucial to understand causes and consequences of entrepreneurs’ prior failure experiences (Burton et al. 2016; Kang and Uhlenbruck 2006; Parker 2013; Parker and Van Praag 2012; Ucbasaran et al. 2013; Ucbasaran et al. 2006). Regarding the determinants, Mellahi and Wilkinson (2004, p. 32) explained organisational failures as the effects produced by ecological, environmental, organisational, and psychological conditions. Similarly, Kang and Uhlenbruck (2006, p. 49) argue that entrepreneurial decisions are dynamic/cyclic (i.e., entries, exits, re-entries, and permanence in a market) given the influence of diverse personal, organisational and environmental conditions. Inspired by these determinants, Khelil (2016, p. 84) proposed a typology of entrepreneurs based on the degree of influence of individual, organisational, and environmental conditions during business failure. Regarding the consequences, Cope (2011, p. 35) explained the link between the learning process and business failure outcomes in terms of individuals’ human and social capital. These learning dimensions predict individuals’ motivations for entrepreneurial re-entry. In this vein, Cardon et al. 2011, p. 83) explored the social norms generated by business failures such as the social stigma of failure, the legitimacy of working as an entrepreneur, the individuals’ view, and their financial problems. To complement, Jenkins et al. (2014, p. 22) examined entrepreneurs’ responses to firm failure in terms of their situation, their appraisal and their griefs. These appraisals and griefs tend to decline as the number of failures increases. Currently, Funken et al. (2018, p. 6) contribute with the understanding of the error mastery orientation that occurs whether or not problems result in entrepreneurial learning because of reflective processes and emotions.

There is a consensus in the literature about the dual role of individual and environmental condition in business failure. Based on previous studies, each business exit and re-entry is a unique story narrated by individual needs (financial rewards, human capital, and close relationships); by societal pressures (social norms about failure stigma, gender inequality, and legitimacy of entrepreneurs), and by environmental conditions (legislation, financial system, labour market conditions). However, how do individual and environmental conditions influence the quality and speed of entrepreneurs’ re-entry after business failure? By adopting a Schumpeterian perspective, Henrekson and Sanandaji (2019) defined quality in terms of innovative entrepreneurship (linked to the creation of jobs and economic transformation) and non-innovative entrepreneurship (self-employment initiatives). In this vein, Dencker et al. (2019) debated the re-definition of quality in terms of opportunity and necessity. Regarding speed, Lin and Wang (2019) and Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue (2019) understood re-entry speed as the time “n” that it takes to start a new business (in t+n) from the moment “t0” associated with a business failure/exit. Then, an accelerated/retarded re-entry will be influenced by individual and contextual conditions (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019).

In this study, therefore, we analyse the environmental and individual determinants of entrepreneurial re-entries in emerging economies after failure based on the theoretical foundations of (a) the institutional economy theory (North 1990) to examine the formal environmental conditions (ecosystem) and informal environmental conditions (social norms); and (b) the theoretical foundations of individual human capital (Becker 1993) and individual social capital (Baron and Markman 2000) to examine the role of individuals’ skills, experiences and relationships. Concretely, the theoretical foundations help to understand the speed of entrepreneurial re-entries (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019; Lin and Wang 2019) as well as the quality of the ventures created after a business failure (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019).

Proposed conceptual model and propositions

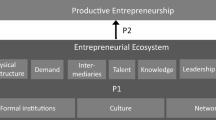

The first determinant of entrepreneurial re-entry into emerging economies after a business exit is the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Institutional economic theory has contributed with a better understanding about the role of formal conditions (support programs, regulations, tax reforms) on entrepreneurial activity in emerging economies (Aidis et al. 2008, 2012; Bruton et al. 2013; Levie et al. 2014; Vaillant and Lafuente 2007). Prior studies have explained exit/entry rates with the absence of supporting institutions (Chacar et al. 2010; Mair et al. 2007) as adequate fiscal regulations, banking frameworks (Haselmann and Wachtel 2010; Kerr and Nanda 2009; Stephen and Wilton 2006), labour market regulations (Fu et al. 2018), and market regulations or entry barriers (Javalgi et al. 2011; Lutz et al. 2010). Ongoing academic debates on environmental conditions have mainly been oriented to the ecosystems’ pillars that support high-growth entrepreneurship (Acs et al. 2017; Brown and Mason 2017). In this understanding, an entrepreneurial ecosystem comprises elements that foster entrepreneurial activity such as open markets, human capital, funding agents, infrastructure, mentors, regulatory frameworks, education systems, and scientific agents (Mason and Brown 2013, 2014; Stam 2014, 2015).

After failure, potential re-entrepreneurs possess a competitive advantage from knowing how the market and the entrepreneurial ecosystem work (Guerrero and Espinoza-Benavides 2020). Therefore, the entrepreneurial re-entry decision depends on market conditions that are crucial for identifying new opportunities in similar or different sectors (Atsan 2016), on the creation of mentorship programs with ex-entrepreneurs for reducing the personal barriers of new entrepreneurs (Cannon and Edmondson 2001, 2005; Cope 2011; Walsh 2017), on the regulatory framework that defines the procedures, duties and support programs for new entries o re-entries (Westhead et al. 2003), on the re-evaluation of financial practices for accessing public/private sources of capital (Chakrabarty and Bass 2013; Cuthbertson and Hudson 1996; Walsh and Cunningham 2016), on the tax policies for entrepreneurial new entries or re-entries (Gentry and Hubbard 2000), and on the attraction/retention of talented people that are required for building teams (Hsu et al. 2017b). As a consequence, entrepreneurial ecosystems influence the identification of opportunities and the quality of re-entries (Mair et al. 2007). In this respect, Fu et al. (2018) argue that labour market rigidity not only influences the re-entry of experienced entrepreneurs, but also the magnitude of this influence depends on the work status of the individual at the moment of re-entry. This means that potential re-entrepreneurs respond differently because the opportunity cost of those that are not employed (by necessity) differs from those that are exploring a new business opportunity (by opportunity). The quality of entrepreneurship is a relevant factor that explains the growth of a country’s competitiveness (Cardon et al. 2011; Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019; Rusu and Dornean 2019). On the other hand, environmental conditions also determine the re-entry speed after a business failure (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019). Favourable entrepreneurial ecosystems enhance accelerated re-entries of experienced entrepreneurs when they are familiar with the support conditions for new ventures (Chowdhury et al. 2019; Fu et al. 2018; Hsu et al. 2017b; Lin and Wang 2019; Simmons et al. 2016). Unfavourable entrepreneurial ecosystems characterised by unclear bankruptcy laws will retard new entries (Lee et al. 2011; Peng et al. 2010; Simmons et al. 2018).

In the assumption that re-entrepreneurs are involved in emerging economies characterised by fostering entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions, we propose the following:

-

P1: Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions determine entrepreneurial re-entries

-

P1a: Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions determine the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (necessity or opportunity) in emerging economies

-

P1b: Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions determine the speed of entrepreneurial re-entries (accelerated or retarded) in emerging economies

The second determinant of entrepreneurial re-entry into emerging economies after a business exit is the societal perception about entrepreneurship (social norms). Institutional economic theory has also contributed with a better understanding of the role of informal conditions (e.g., social norms, values, culture) on entrepreneurial activity in the context of emerging economies (Bruton et al. 2010). Social norms dictate legitimacy and individuals face social pressure if they do not act according to those norms (Meek et al. 2010); therefore, values and norms at group-level determine the individual-level decisions. For example, business failure exposes entrepreneurs to the stigma of negative social judgments and to the sanctions created by society for those who decide to re-enter the game (Cardon et al. 2011; Shepherd and Haynie 2011; Simmons et al. 2014; Singh et al. 2015). If those informal conditions influence behaviours and emotions (Funken et al. 2018), we expect that societal perceptions will clarify entrepreneurship dynamics (entry, permanence, exit, and re-entry) across countries for us. Hessels et al. (2011) analysed exit and entrepreneurial engagement in 24 countries across the globe. In their control variables, it is possible to identify a negative propensity to re-entry in advanced European economies (e.g., Denmark, Greece, Spain, and Sweden), a propensity to re-entry in the U.S. economy as well as in other emerging economies (e.g., Argentina, Croatia and Slovenia). It is also linked with the European investors’ stigma of not investing money in re-entrepreneurs as a sanction of failure without considering business exits as the opportunity to gain more experience that increase the probabilities of success (Cope 2011; Cope et al. 2004; Parker 2013; Yamakawa et al. 2015; Zacharakis and Meyer 1999). Therefore, the entrepreneurial re-entries are delayed or not considered in countries with these types of sanctions to business failure (Cardon et al. 2011). An alternative to identify societal perception about entrepreneurship is to explore the content of social media, the social status and respect for successful entrepreneurs, and the consideration of being an entrepreneur as a desirable profession (Bosma 2013). In this vein, social norms could influence the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries. Social norms associated with negative emotions reduce aspirations and orientations in entrepreneurial re-entry (Cardon et al. 2011; Jenkins et al. 2014). For optimistic and confident re-entrepreneurs, negative emotions are treated as the opportunity to capture the societal recognition (Khelil 2016). It explains that the quality of potential re-entrepreneurs will be influenced by how social norms are translated into negative emotions (by necessity) or recognition (by opportunity). In the same vein, the social stigma of business failure will condition the speed of entrepreneurial re-entries (Cardon et al. 2011; Cope 2011; Jenkins et al. 2014; Lin and Wang 2019). If social stigma affects negatively, re-entrepreneurs will assume the (social) costs of failure and this cost will retard new entrepreneurial entries (Lin and Wang 2019).

In the assumption that re-entrepreneurs are involved in emerging economies with social norms for business failure and entrepreneurship, we propose the following:

-

P2: Societal perceptions about entrepreneurship determine entrepreneurial re-entries

-

P2a: Societal perceptions about entrepreneurship determine the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (necessity or opportunity) in emerging economies

-

P2b: Societal perceptions about entrepreneurship determine the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (accelerated or retarded) in emerging economies

The third determinant of entrepreneurial re-entry into emerging economies after a business exit is the re-entrepreneur’s human capital. Human capital theory has contributed to the entrepreneurship literature with a better understanding about the role of skills, knowledge, abilities and experiences in entrepreneurial entry, permanence, exit, and re-entry (Fu et al. 2018; Hessels et al. 2011; Parker and Van Praag 2012; Stam et al. 2008). Prior studies have adopted the distinction of general and specific human capital proposed by (Becker 1993). General human capital is comprised of formal education and experiences that are useful for developing any occupation or economic activity; while specific human capital is comprised of knowledge, skills, and experiences that are useful for exploring/exploiting business opportunities (Amaral et al. 2011; Ucbasaran et al. 2010, 2013). Business failure literature recognises that the lack of specific human capital (e.g., skills, abilities and experiences associated with managing resources, knowing markets or sectors, measuring affordable risks, etc.) is aligned with the wrong business decisions taken by the entrepreneur (Atsan 2016; Ucbasaran et al. 2013).

After business failure/exit, it is expected that the re-entrepreneur will have improved their managerial, entrepreneurial, and funding skills (Amaral et al. 2011; Ucbasaran et al. 2006), as well as having gained experience to identify feasible opportunities, customers, competitors, suppliers, and known the attitudes of venture capital investors towards entrepreneurs with previous exits (Cope 2011; Cope et al. 2004; Jenkins et al. 2014). As a result, improved skills and experiences after business failure reinforce the quality and the speed of entrepreneurial re-entries (Amaral et al. 2011; Fu et al. 2018; Stam et al. 2008). Nevertheless, if psychological disappointments are not overcome after business failure/exit, human capital will be useful for looking for new occupational choices instead of entrepreneurial re-entries (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019; Sørensen and Sharkey 2014) or delaying entrepreneurial re-entries (Amaral et al. 2011). Along the same lines, more experienced individuals will be able to identify more opportunities than those that have not gained experience after failure (Funken et al. 2018; Jenkins et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2019). The quality of the business opportunities will vary depending on the human capital of re-entrepreneurs (Hessels et al. 2011). Similarly, the speed of re-entries will depend on the experience and networks acquired in previous entrepreneurial initiatives. Individuals with specialised entrepreneurial knowledge will invest less time in creating a new venture (Amaral et al. 2011; Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019; Lin and Wang 2019). On the contrary, individuals with less specialised entrepreneurial knowledge will invest more time in creating a new venture (Hsu et al. 2017a).

In the assumption that re-entrepreneurs have improved skills and experience before entry into their emerging markets, we propose the following:

-

P3: Human capital determines the entrepreneurial re-entry

-

P3a: Human capital determines the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (necessity or opportunity) in emerging economies

-

P3b: Human capital determines the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (accelerated or retarded) in emerging economies

The fourth determinant of entrepreneurial re-entry into emerging economies after a business failure is the re-entrepreneur’s social capital. The social capital theory has also contributed to the entrepreneurship literature with a better understanding of the role of networks on entrepreneurial dynamics (Davidsson and Honig 2003; Lechner and Dowling 2003; Neumeyer et al. 2019; Stam et al. 2008). By adopting this approach, the notion is that entrepreneurs are socially embedded agents who leverage vital resources from their social environment to develop and grow ventures (Baron and Markman 2000). After business exits, it is expected that entrepreneurs have more nodes linked by a set of relationships with close people (family and friends) and people from other organisations (government, banks, suppliers, investors, entrepreneurs, and associations) (Ucbasaran et al. 2013, 2009; Ucbasaran et al. 2010). If their nodes support re-entrepreneurs, they will obtain vital resources, market information, and, consequently, will be better prepared to identify and to take advantage of new opportunities.

Social capital intensity will provide a mechanism for absorbing previous business exit experiences and reinforcing the re-entrepreneur’s optimism for not delaying the entrepreneurial re-entry decision (Nielsen and Sarasvathy 2011). If re-entrepreneurs are actively involved in networks with other entrepreneurs, this social capital could produce normative effects or pressure to re-enter with better entrepreneurial initiatives (Stam et al. 2008). As a consequence, the type their entrepreneurial initiatives also vary depending on social capital (Cope 2011; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019). The quality and the speed of a new venture depends on the entrepreneur’s relationships with family (Khelil 2016; Lin and Wang 2019), potential investors (Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019), mentors, and agents of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Rusu and Dornean 2019). Social partners also contribute with elements for an accelerated/retarded re-entry (Baù et al. 2017).

In the assumption that the re-entrepreneurs’ social contacts and networks provide the opportunity for support and re-entrepreneurs do not re-enter alone into emerging markets, we propose the following:

-

P4: Social capital determines entrepreneurial re-entry in emerging economies

-

P4a: Social capital determines the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (necessity or opportunity) in emerging economies

-

P4b: Social capital determines the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (accelerated or retarded) in emerging economies

Research context and methodology

Methodological design

In previous studies, the most highlighted limitation in business exit/failure has been the lack of collected data given the stigmatisation of failure (Shepherd and Haynie 2011; Singh et al. 2015). Re-entry studies face similar difficulties, particularly in the context of emerging economies (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2018; Williams et al. 2019). Given the nature of this phenomenon, this study adopts a retrospective analysis of multiple entrepreneurial re-entry cases within an emerging economy. This methodology provides us with a broad perspective of entrepreneurial re-entries across the globe without details of the reasons for the exit, learning and transition process, motivations behind a re-entry, results in the current re-entry experience, as well as the role of individual, organisational and environmental conditions. For this purpose, we designed a retrospective multiple case study analysis that is a type of longitudinal case design in which all data, including first-person accounts, are collected when the majority of the events and activities under study have already occurred, and the outcomes of these events and activities are known (Street and Ward 2010). This means the most recent re-entries have occurred before the data collection process.

Research setting and data collection

We chose Chile as a proper emerging economy research setting for three reasons. First, Chile is the high-income economy across the globe with the highest percentage of entrepreneurs and re-entries (Bosma and Kelley 2019). Second, Chile is ranked as the top ten emerging economies in Latin-America during the last ten years (United Nations 2019). Third, Chile has made efforts in fostering entrepreneurship and in building an entrepreneurial ecosystem that is positioned in the top list of ecosystems across the globe (CORFO 2018; Herrmann et al. 2012).

The data collection process adopts the triangulation suggested by Yin (2003) that consists of combining multiple sources to gather data such as interviews as well as constant information with secondary sources such as official records, company websites, financial reports, and social media records. Regarding interviews, the criteria for selecting re-entrepreneurs were individuals that are currently involved in a re-entry after facing a business exit in the last three years; micro, small and medium-size new ventures; currently motivated by necessity or by an opportunity and covering a gender and industry distribution. Their identification was with the support of local development offices located across the country. We initially contacted 50 re-entrepreneurs but only 20 re-entrepreneurs decided to participate in our study. Table 1 shows the general profile of these re-entrepreneurs.

Following the proposed conceptual framework, we designed a protocol and a semi-structured interview that allowed us to capture information about the business failure and re-entry journey of this 20 re-entrepreneurs. The fieldwork was developed during the last semester of 2018. On average, each interview had a duration of two and a half hours and was recorded and transcribed. By confidentiality agreements, the identity of each re-entrepreneur was treated anonymously. The data was coded and analysed according to the impacts identified in the literature (Miles et al. 1994). The analysis of the encoded data involved the search for common patterns among cases (Eisenhardt 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007) in order to identify findings that were framed in the business failure and re-entry literature, thereby strengthening the internal validity of the research. By adopting the criteria proposed by Audretsch (2012); Dencker et al. (2019) and Henrekson and Sanandaji (2019), the quality was approximated through the re-entrepreneur’s motivations: the exploitation of new opportunities (ERO) or working for themselves (ERN). Furthermore, we included the business orientations: high-tech re-entries with a high-growth orientation (HTG), and non-high-tech re-entries without a high-growth orientation (NHTG). By adopting the criteria proposed by Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue (2019), the speed was approximated by the time between the business failure and the re-entry: the accelerated re-entry implies the creation of a new venture within the first year after failure, and the retarded re-entry implies the development of an entrepreneurial initiative after one year of the business failure (see Appendix).

Findings

Table 2 summarises a narrow dissection of the entrepreneurial re-entry trajectory of Chileans after their business failure. We found the following four patterns.

The first pattern is the NHTG by necessity. This group is composed of four re-entrepreneurs with technical education distributed by gender and currently enrolled in their second business after at least ten years of entrepreneurial experience [A, F, G, and I]. This group is very critical of themselves and the societal reactions to business failure, as well as very constructive regarding the role of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. This group recognised that their business exit causes were a consequence of the lack of skills (specific human capital), family issues that provoked a fragile relationship with partners (social norms) and not paying attention to competitors and market conditions (entrepreneurial ecosystem). During their failure they preferred to face the consequences alone to avoid the criticism of their family (social norms). In the Khelil (2016, p. 86) typology, this group has certain similitudes with the megalomaniac entrepreneurs that focus on individual constraint instead of environmental constraint. After failure, this group decided to focus on two crucial challenges: improving managerial/leadership skills and understanding legal agreements to avoid fragile relationships with potential investors (family and friends). Their entrepreneurial re-entry impacted them demonstrating self-fulfilment, a reduction of personal barriers/traumas, a growth orientation supported by partners, and social commitments with minor groups of their localities (kids and students). This group gains optimism and works for legitimising the work of entrepreneurs in society (Cardon et al. 2011). However, their self-evaluation demands improvements in specific skills like the management of resources and fundraising that are important for achieving projects and generate more added value for their stakeholders. They perceive favourable attitudes from families, employees and clients. They evaluate the mentorship and governmental support received from the ecosystem very well but recognise that the financial sector and the educational system should be reinforced. Their exposure to their prior failure and financial needs have moderated their failure’s appraisal and griefs (Jenkins et al. 2014). After self-learning during a few months (see Cope 2011), they decided on an accelerated re-entry into the same markets motived by personal challenges, and looking for business goals, financial rewards, and social recognition. Although this group can scale up their business, they chose a low profile to maintain the managerial/financial control. The environmental conditions directly influenced an accelerated re-entry in this group.

The second pattern is HTG by necessity. This group is composed of five re-entrepreneurs with higher education distributed by gender and currently enrolled in their third venture after at least nine years of entrepreneurial experience [B, C, D, H, and J]. Their entrepreneurial initiatives are high-tech and high-growth oriented. This group recognises that their business failure was influenced by the lack of skills (specific human capital), lack of financial health and an unskilled team (organisational), as well as by the inappropriate regulations in labour, finance and the market (ecosystem conditions). In the Khelil (2016, p. 86) typology, this group has certain similitudes with the dissatisfied lord entrepreneurs that focus on individual-social constraints motivated by their ambitious goals, team weaknesses and environmental barriers. After failure experiences, most challenges were to find a balance between the family and the business, the establishment of metrics for client follow up to reinvent the quality of products/services and facing the market competitors. Therefore, this group decided to improve their specific human capital (skills and business language) that was very useful for building teams and managing available resources. After self, relational and management learning (see Cope 2011), the re-entry pushing factors were personal-family goals and social impact in their localities. This group created new technological business models into similar/different markets with the support of their families. The entrepreneurial re-entry produced very positive results such as their fulfilment, the reduction of personal barriers, excellent indicators (better performance, growth, consolidation, generation of employment), and impact on vulnerable social groups. The failure impacts were positively related to individuals, finances and access to capital (Cardon et al. 2011). In terms of self-evaluation, they evaluate their generic and specific human capital very well. In terms of the business, they very positively evaluate the entry into new sectors, the sustainability of the business model as well as the consolidation but they still demand capital and more employees. In terms of society, they still perceive that the population does not thoroughly understand failure and re-entry. In terms of the ecosystem, the only positive perception is the mentorship received from the support infrastructures, but the rest of conditions are not well perceived (lack of talent, education and financial system). Their experience and exposure to prior failures have moderated their personal/business appraisals and griefs (Jenkins et al. 2014). The quality-speed was a trade-off (Dencker et al. 2019). On the one hand, necessity motivates an accelerated re-entry without assuming any risk or taking advantage of innovation. These findings are similar to Henrekson & Sanandaji’s no-Schumpeterian classification of entrepreneurs. On the other hand, the negative consequences of business failure at the family level limited the aspirations, the self-efficacy, and the entry’ speed. It implies the direct and the moderated effect of family on the accelerated/retarded re-entry (Lin and Wang 2019).

The third pattern is the NHTG by opportunity. This group is composed of three re-entrepreneurs with higher education, mostly woman and currently enrolled in forth business after at least three years of entrepreneurial experience [M, T and U]. Their failure antecedents were associated with social pressures associated with gender (social norms) and the lack of skills for managing liquidity (specific human capital) influenced by the limitations of the financial market (ecosystem conditions). Although having the same non-high-tech and high-growth orientation, they are more critical than the first group. In the Khelil (2016, p. 86) typology, this group has certain similitudes with the confused entrepreneurs that focus on social and environmental constraints (absence of financial support) with the exception that their ventures are not driven by necessity (unemployment) and, as well as with the megalomaniac entrepreneurs, they tend to overestimate their expertise (mostly in the cases of woman re-entrepreneurs). During the failure stage, they received support from families, some governmental programs, and from business angels. After self-learning, the venture and relational learning (see Cope 2011), they have a profound transformation to be persistent with the business challenges such as learning how to convert ideas into actions and face entry barriers in new markets, as well as learning about the nature and management of relationships to avoid losing friendships by business liabilities. After this learning period, they decided to re-enter, motivated by personal challenges, family goals, financial rewards and social recognition. The impacts of their entrepreneurial re-entry after failure were self-fulfilment, better performance with growth orientation and the producing of some social actions in their localities. The business failure transformed individual perception and the individual’s role in reducing the social stigmatisation of failure (Cardon et al. 2011). According to their self-evaluations, they recognise having excellent technical and market knowledge required for improving the quality of products/services and contributing to their clients’ satisfaction. However, they also recognise that they still need to work on managing liabilities. Moreover, their entrepreneurial ecosystem provides support and skilled personnel with minimal options for accessing credits. Socially, they have received the solidarity of close people but still perceive the stigmatisation of failure and re-entry from the rest of society. Indistinctly from the context, the notion behind this group is that network connectivity and distribution of social capital are significantly different by gender (Ibáñez et al. 2020). Similarly, Neumeyer et al. (2019) found that female entrepreneurs engaged in high-growth ventures showed a lower degree of bridging social capital than male entrepreneurs. If we transfer this to female re-entrepreneurs, the complexity increased with social norms where a man represents more aggressive/managed growth, while the woman represents more lifestyle and survival. Maybe it is evidencing the ecosystem inefficiencies that arise from multiple interactions between entrepreneurs and institutions (Simmons et al. 2018). This group takes time for preparing their re-entrepreneurial process influenced by the support of their families and their human capital. Given the higher educational level, the retarded entry is influenced by choosing the labour market as a mechanism to gain/save money. Baù et al. (2017) found similar findings in their predictions in re-entrepreneurship speed.

The last pattern is the HTG by opportunity. Eight re-entrepreneurs compose this group with higher education involved in manufacture and services. The younger people created more business in a short period and elder people created less business with more years of entrepreneurial experience. Therefore, this group has the highest experience and the most critical view of their entrepreneurial ecosystem [K, L, N, O, P, Q, R, and S]. Their failure antecedents were associated with individual constraints (lack of vision), organisational constraints (unskilled team, the lack of liquidity), and environmental constraints (contractual laws, exchange rates, and culture). During their business failure, they received support from close people (family and friends) and specialised people (networks). In the Khelil (2016, p. 86) typology, this group has certain similitudes with the bigtime gambler entrepreneurs that focus on the persistence on the venture health although that is very confused and they are disappointed with their perceived environmental barriers/obstacles. After failure, their main challenges were the persistence for taking the decisions on time and the attraction of talent and capital. After self-learning, the venture and relationships (Cope 2011), they learn to determine an affordable loss, to separate friendships and business, and trust more in their partners/experts. They decided to re-enter motivated by personal challenges, by financial rewards, by looking for managing talent and resources, and by societal recognition. The rewards obtained from their re-entries have been personal (self-fulfilment and well-being), financial (business success and regional trademarks), social (supporting minor groups), and at the ecosystem level (creating entrepreneurial networks and associations). They evaluated their (general and specific) human capital very well and are very satisfied with their high impact venture and their rapid speed growth. This group tried to reduce the majority of the negative impacts associated with failure (Cardon et al. 2011). Based on their evaluations, this group is very critical of the entrepreneurship ecosystem mentioning that the majority of the conditions should be improved (e.g., venture capital, business angel networks, access to bank credits, and the lack of skilled people); notably, they recognised that are still facing the social consequences of failure stigma (social norms). This group is characterised by investing more time to re-enter through the influence of multiple elements: (a) the family support, (b) their social capital, (c) their higher educational level, and their perception of the ecosystem. Also, the higher level of innovation/technology of their initiatives demands time and multiple sources of funding. Therefore, they are usually looking for opportunities in combination with paid employment.

There is a direct relationship between the speed and the quality across the four patterns of re-entrepreneurs. An accelerated speed is encouraged by non-technological re-entrepreneurs (NHGT necessity and NHGT opportunity) with more than ten years of experience as entrepreneurs. Schumpeterian entrepreneurs (HGT Necessity and HGT Opportunity) adopted a retarded re-entry with less than four years of experience. Therefore, the entrepreneurial experience is the most critical determinant of the speed/quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (Amaral et al. 2011; Ucbasaran et al. 2009).

Discussion and conclusion

Contrasting our findings with the literature (Table 3), we find arguments to reinforce our initial propositions and to revise the proposed conceptual model incorporating mechanisms that link business failure and entrepreneurial re-entries in emerging economies (Fig. 1).

We confirmed that failure is provoked by several limitations of the individual, weaknesses of the business, and environmental constraints (Khelil 2016). The initial reaction is associated with negative emotions because of social pressures (Cardon et al. 2011) and loss of resources or personal motivations (Jenkins et al. 2014). After an introspective period, individuals evaluate the causes of failures, identify business strengths/weaknesses, and could be prepared to take actions about them (Cope 2011). However, a learning process will be observed in individuals that adopted a failure mastery orientation that is a proactive and positive perspective for handling failure (Funken et al. 2018). This perspective explains why individuals are more likely to identify business opportunities than those that only adopt a negative and reactive perspective to handling failure (Mair et al. 2007). Nevertheless, in the context of emerging economies, the transformation of failure learning into an entrepreneurial re-entry action is moderated by institutional voids and supporting ecosystems (Simmons et al. 2018; Fu et al. 2018; Guerrero and Espinoza-Benavides 2020; Guerrero et al. 2020), by the prior social capital captured from the ecosystem (Neumeyer et al. 2019), and by the improved skills, knowledge, and experience gained after failure (Hsu et al. 2017b). The speed from business learning to re-entry (accelerated or retarded) and the quality of entrepreneurial re-entries (opportunity or necessity) will be moderated by the institutional conditions detected in the economy, as well as by the human and social capital that the re-entrepreneur possesses. As a result, our study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature with the revised conceptual model to explore the role of individual and environmental determinants in the trajectory from business failure to entrepreneurial re-entry in the context of emerging economies.

Our study has several limitations. First, a retrospective methodology has advantages and disadvantages. This strategy provides detailed information about the re-entry trajectory in a Latin-American emerging economy. Despite these insights, their generalisation demands the confirmation and the saturation of these findings in multiple cases in different emerging economies. A natural extension of this study could be replicated in multiple research settings, as well as extending the collection for testing our propositions. Second, aligned to the first limitation, we asked re-entrepreneurs about past events with an emotional impact. Emotions should be also considered in this type of study for multiple reasons (Cardon et al. 2011). Third, the complexity for accessing information conditioned some elements included in the theory development. We adopted similar metrics to previous studies to understand the re-entry’ speed and quality (Audretsch 2012; Dencker et al. 2019; Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2019; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019). However, time and space may be influenced by multiple agents (re-entrepreneurs, families, institutions, networks, venture capital, society). This limitation demands re-conceptualizing re-entry speed/quality by using mixed conceptual/methodological approaches (Shaw et al. 2018). We also could explore other research techniques for improving the reliably of the data collection process such as triangulation (Yin 2003), longitudinal studies, ethnography studies, as well as collecting quantitative data. However, the challenge will be the stigmatisation of failure that made people unwilling to share their experiences.

One main implication emerges from our finding. For policymakers involved in the design of policies and that also orchestrate entrepreneurship ecosystems (Table 3), there is a general assumption that entrepreneurship ecosystems in emerging economies help to reduce the effects of institutional voids. Although the policymakers’ efforts for configuring an entrepreneurial ecosystem, the Chilean ecosystem is evidencing weaknesses regarding the social stigmatisation of failure and inefficiencies in the interaction between re-entrepreneurs and institutions (see Simmons et al. 2018; Guerrero andd Espinoza-Benavides 2020). The legitimation starts with a re-definition of the rules of the game in the access to credits or capital (Guerrero et al. 2020). Actors should change the taboo of business failure and re-consider it as an experience instead of a sanction. For entrepreneurial mentors, it is essential to understand the trade-off between quality and speed of re-entry (Dencker et al. 2019). Our findings show that policymakers do not understand how to support entrepreneurs who faced a business failure and decide to create a new venture. By taking the opinion of the HTG by opportunity re-entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial mentors may create scenarios where entrepreneurs share their failure experiences. Mentors, re-entrepreneurs and policymakers may co-design initiatives to support and influence the quality/speed of re-entrepreneurs. For re-entrepreneurs, the trajectory from failure to re-entry should be considered as an individual and collective journey. Sharing experiences allows for changing the negative perception of failure and becoming role models for others that are facing similar situations. Indeed, this type of study also contributes to legitimise the socio-economic contributions of re-entrepreneurs who re-enter after a business failure.

References

Acs, Z. J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D. B., & O’Connor, A. (2017). The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9864-8.

Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2008). Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: A comparative perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 656–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.005.

Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. M. (2012). Size matters: Entrepreneurial entry and government. Small Business Economics, 39(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9299-y.

Amankwah-Amoah, J. (2018). Revitalising serial entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from a newly emerging economy. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 30(5), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2017.1313403.

Amankwah-Amoah, J., Boso, N., & Antwi-Agyei, I. (2018). The effects of business failure experience on successive entrepreneurial engagements: An evolutionary phase model. Group & Organization Management, 43(4), 648–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601116643447.

Amaral, A. M., Baptista, R., & Lima, F. (2011). Serial entrepreneurship: Impact of human capital on time to re-entry. Small Business Economics, 37(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9232-4.

Atsan, N. (2016). Failure experiences of entrepreneurs: Causes and learning outcomes. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.11.054.

Audretsch, D. B. (2012). Determinants of high-growth entrepreneurship.

Baron, R. A., & Markman, G. D. (2000). Beyond social capital: How social skills can enhance entrepreneurs success. Academy of Management Executive, 14(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2000.2909843.

Baù, M., Sieger, P., Eddleston, K. A., & Chirico, F. (2017). Fail but try again? The effects of age, gender, and multiple-owner experience on failed entrepreneurs’ Reentry. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 41(6), 909–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12233.

Becker, G. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (third edit). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press Retrieved from https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=9t69iICmrZ0C&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Human+capital+becker&ots=WxCvl_UvkS&sig=JORQvL46NrxiLbt6eS5cpinyBIo.

Bosma, N. (2013). The global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM) and its impact on entrepreneurship research. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 9(2), 143–248. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000033.

Bosma, N., & Kelley, D. (2019). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2018/2019 Global Report. (global entrepreneurship research association, Ed.). Global entrepreneurship research association.

Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9865-7.

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H. L. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x.

Bruton, G. D., Filatotchev, I., Si, S., & Wright, M. (2013). Entrepreneurship and strategy in emerging economies. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(3), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1159.

Burton, M. D., Sørensen, J. B., & Dobrev, S. D. (2016). A careers perspective on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12230.

Cannon, M. D., & Edmondson, A. C. (2001). Confronting failure: Antecedents and consequences of shared beliefs about failure in organizational work groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.85.

Cannon, M. D., & Edmondson, A. C. (2005). Failing to learn and learning to fail (intelligently): How great organizations put failure to work to innovate and improve. Long Range Planning, 38(3 SPEC. ISS.), 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2005.04.005.

Cardon, M. S., Stevens, C. E., & Potter, D. R. (2011). Misfortunes or mistakes?. Cultural sensemaking of entrepreneurial failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.06.004.

Chacar, A. S., Newburry, W., & Vissa, B. (2010). Bringing institutions into performance persistence research: Exploring the impact of product, financial, and labor market institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7), 1119–1140. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.3.

Chakrabarty, S., & Bass, A. E. (2013). Encouraging entrepreneurship: Microfinance, knowledge support, and the costs of operating in institutional voids. Thunderbird International Business Review, 55(5), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21569.

Chowdhury, F., Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2019). Institutions and entrepreneurship quality. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 51–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718780431.

Cope, J. (2011). Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 604–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.06.002.

Cope, J., Cave, F., & Eccles, S. (2004). Attitudes of venture capital investors towards entrepreneurs with previous business failure. Venture Capital, 6(2–3), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691060410001675965.

CORFO. (2018). Entrepreneurial ecosystem in Chile. Santiago - Chile.

Cuthbertson, K., & Hudson, J. (1996). The determinants of compulsory liquidation in the U.K. The Manchester School of Economic & Social Studies, 64(3), 298–308.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6.

Dencker, J., Bacq, S. C., Gruber, M., & Haas, M. (2019). Reconceptualizing necessity Entrepreneurship: A Contextualized Framework Of Entrepreneurial Processes Under The Condition Of Basic Needs. Academy of Management Review. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2017.0471

DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.24160888.

Fu, K., Larsson, A. S., & Wennberg, K. (2018). Habitual entrepreneurs in the making: How labour market rigidity and employment affect entrepreneurial re-entry. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0011-y.

Funken, R., Gielnik, M. M., & Der Foo, M. (2018). How can problems be turned into something good? The Role of Entrepreneurial Learning and Error Mastery Orientation. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice., 44, 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718801600.

Gentry, W. M., & Hubbard, R. G. (2000). Tax policy and entrepreneurial entry. American Economic Review, 90(2), 283–287. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.2.283.

Guerrero, M., & Peña-Legazkue, I. (2019). Renascence after post-mortem: The choice of accelerated repeat entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 52(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0015-7.

Guerrero, M., & Espinoza-Benavides, J. (2020). Does entrepreneurship ecosystem influence business re-entries after failure? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00694-7

Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2017). The dark side of entrepreneurial ecosystems in emerging economies: Exploring the case of Mexico. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2017(1), 12941. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2017.12941abstract.

Guerrero, M., Liñán, F., & Cáceres-Carrasco, F. R. (2020). The influence of ecosystems on the entrepreneurship process: A comparison across developed and developing economies. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00392-2

Haselmann, R., & Wachtel, P. (2010). Institutions and Bank behavior: Legal environment, legal perception, and the composition of Bank lending. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 42(5), 965–984. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4616.2010.00316.x.

Henrekson, M., & Sanandaji, T. (2019). Measuring Entrepreneurship: Do Established Metrics Capture Schumpeterian Entrepreneurship? In Measuring entrepreneurship: Do established metrics capture Schumpeterian entrepreneurship? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 104225871984450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719844500.

Herrmann, B., Marmer, M., Dogrultan, E., & Holtschke, D. (2012). Startup ecosystem report 2012: part one. Start-up Ecosystem Report 2012. Part One. Start-up Genome’s Start-up Compass Sponsored by Telefónica.

Hessels, J., Grilo, I., Thurik, R., & van der Zwan, P. (2011). Entrepreneurial exit and entrepreneurial engagement. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 21(3), 447–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-010-0190-4.

Hsu, D. K., Wiklund, J., & Cotton, R. D. (2017a). Success, failure, and entrepreneurial Reentry: An experimental assessment of the veracity of self-efficacy and Prospect theory. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 41(1), 19–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12166.

Hsu, Dan K, Shinnar, R. S., Powell, B. C., & Betty, C. S. (2017b). Intentions to reenter venture creation: The effect of entrepreneurial experience and organizational climate. International Small Business Journal, 026624261668664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616686646

Ibáñez, M. J., Guerrero, M., & Mahto, R. V. (2020). Women-led SMEs: Innovation and collaboration→ performance? Journal of the International Council for Small Business. https://doi.org/10.1080/26437015.2020.1850155.

Javalgi, R. (Raj) G., Deligonul, S., Dixit, A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2011). International market Reentry: A review and research framework. International Business Review, 20(4), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2010.08.001.

Jenkins, A. S., Wiklund, J., & Brundin, E. (2014). Individual responses to firm failure: Appraisals, grief, and the influence of prior failure experience. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.10.006.

Kang, E., & Uhlenbruck, K. (2006). A process framework of entrepreneurship: From exploration, to exploitation, to exit. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 47–71 Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/openview/e8bb281ef16702cdb64b3da6201a0b1e/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29726.

Kerr, W. R., & Nanda, R. (2009). Democratizing entry: Banking deregulations, financing constraints, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(1), 124–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.12.003.

Khelil, N. (2016). The many faces of entrepreneurial failure: Insights from an empirical taxonomy. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(1), 72–94.

Koçak, A., Morris, M. H., Buttar, H. M., & Cifci, S. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit and reentry: An exploratory study of Turkish entrepreneurs. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 15(04), 439–459.

Lechner, C., & Dowling, M. (2003). Firm networks: External relationships as sources for the growth and competitiveness of entrepreneurial firms. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 15(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620210159220.

Lee, S. H., Yamakawa, Y., Peng, M. W., & Barney, J. B. (2011). How do bankruptcy laws affect entrepreneurship development around the world? Journal of Business Venturing, 26(5), 505–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.05.001.

Levie, J., Autio, E., Acs, Z., & Hart, M. (2014). Global entrepreneurship and institutions: An introduction. Small Business Economics, 42(3), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9516-6.

Lin, S., & Wang, S. (2019). How does the age of serial entrepreneurs influence their re-venture speed after a business failure? Small Business Economics, 52(3), 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9977-0.

Lutz, C. H. M., Kemp, R. G. M., & Dijkstra, S. G. (2010). Perceptions regarding strategic and structural entry barriers. Small Business Economics, 35(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9159-1.

Mair, J., Martí, I., & Ganly, K. (2007). Institutional voids as spaces of opportunity. Paper Presented at the European Business Forum; London, UK (31): 34-39.

Mair, J., Martí, I., & Ventresca, M. J. (2012). Building inclusive markets in rural Bangladesh: How intermediaries work institutional voids. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 819–850. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0627.

Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2013). Creating good public policy to support high-growth firms. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9369-9.

Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Academia.Edu. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/download/39222221/0f3175328b38ec3c0d000000.pdf

McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review. Academy of Management, 31, 132–152. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.19379628.

Meek, W. R., Pacheco, D. F., & York, J. G. (2010). The impact of social norms on entrepreneurial action: Evidence from the environmental entrepreneurship context. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(5), 493–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.09.007.

Mellahi, K., & Wilkinson, A. (2004). Organizational failure: A critique of recent research and a proposed integrative framework. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5–6(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-8545.2004.00095.x.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, Michael, A., & Saldaña, J. (1994). Qualitative data analysis A methods (Sourcebook ed.) SAGE.

Nations, U. (2019). Preliminary overview of the economies of Latin America and the Caribbean. Santiago.

Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., Caetano, A., & Kalbfleisch, P. (2019). Entrepreneurship ecosystems and women entrepreneurs: A social capital and network approach. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9996-5.

Nielsen, K., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2011). Who reenters entrepreneurship? And who ought to? An empirical study of success after failure. EMAEE, 2011 Retrieved from http://www.lem.sssup.it/WPLem/documents/papers_EMAEE/nielsen.pdf.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions. Institutional Change and Economic Performance: Cambridge University Press.

Parker, S. C. (2013). Do serial entrepreneurs run successively better-performing businesses? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 652–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.08.001.

Parker, S. C., & Van Praag, C. M. (2012). The entrepreneur’s mode of entry: Business takeover or new venture start? Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.08.002.

Peng, M. W., Yamakawa, Y., & Lee, S. H. (2010). Bankruptcy laws and entrepreneur- friendliness. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 34(3), 517–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00350.x.

Ravindran, B., & Baral, R. (2014). Factors affecting the work attitudes of Indian re-entry women in the IT sector. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 39(2), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090920140205.

Rusu, V., & Dornean, A. (2019). The quality of entrepreneurial activity and economic competitiveness in European Union countries: A panel data approach. Administrative Sciences, 9(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9020035.

Shaw, J. D., Tangirala, S., Vissa, B., & Rodell, J. B. (2018, February 1). New ways of seeing: Theory integration across disciplines. Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management., 61, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.4001.

Shepherd, D. A., & Haynie, J. M. (2011). Venture failure, stigma, and impression management: A self-verification, self-determination view. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 5(2), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.113.

Shepherd, D. A., Wennberg, K., Suddaby, R., & Wiklund, J. (2019). What are we explaining? A review and agenda on initiating, engaging, performing, and contextualizing entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 45(1), 159–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318799443.

Simmons, S. A., Wiklund, J., & Levie, J. (2014). Stigma and business failure: Implications for entrepreneurs’ career choices. Small Business Economics, 42(3), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9519-3.

Simmons, S. A., Carr, J. C., Hsu, D. K., & Shu, C. (2016). The regulatory fit of serial entrepreneurship intentions. Applied Psychology, 65(3), 605–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12070.

Simmons, S. A., Wiklund, J., Levie, J., Bradley, S. W., & Sunny, S. A. (2018). Gender gaps and reentry into entrepreneurial ecosystems after business failure. Small Business Economics, 53, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-9998-3.

Singh, S., Corner, P. D., & Pavlovich, K. (2015). Failed, not finished: A narrative approach to understanding venture failure stigmatization. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(1), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.005.

Sørensen, J. B., & Sharkey, A. J. (2014). Entrepreneurship as a mobility process. American Sociological Review, 79(2), 328–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414521810.

Stam, E. (2014). The Dutch entrepreneurial ecosystem. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2473475.

Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484.

Stam, E., Audretsch, D., & Meijaard, J. (2008). Renascent entrepreneurship. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 18(3–4), 493–507.

Stephen, C., & Wilton, W. (2006). Don’t blame the entrepreneur, blame the government: The centrality of the government in enterprise development. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 14(1), 65–84.

Street, C., & Ward, K. (2010). Retrospective case study. In A. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research. (T. Oaks, Ed.) Thousand Oaks.

Surdu, I., Mellahi, K., Glaister, K. W., & Nardella, G. (2018). Why wait? Organizational learning, institutional quality and the speed of foreign market re-entry after initial entry and exit. Journal of World Business, 53(6), 911–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2018.07.008.

Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (2006). Habitual entrepreneurs experiencing failure: Overconfidence and the Motivation to Try Again. Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1074-7540(06)09002-7

Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (2009). The extent and nature of opportunity identification by experienced entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(2), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.008.

Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., Wright, M., & Flores, M. (2010). The nature of entrepreneurial experience, business failure and comparative optimism. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 541–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.04.001.

Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., & Westhead, P. (2013). A longitudinal study of habitual entrepreneurs: Starters and acquirers. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 15(3), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620210145009.

Vaillant, Y., & Lafuente, E. (2007). Do different institutional frameworks condition the influence of local fear of failure and entrepreneurial examples over entrepreneurial activity? Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(4), 313–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620701440007.

Walsh, G. (2017). Re-entry following firm failure: Nascent technology entrepreneurs’ tactics for avoiding and overcoming stigma. In Technology-based nascent entrepreneurship (pp. 95–117). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59594-2_5.

Walsh, G. S., & Cunningham, J. A. (2016). Business failure and entrepreneurship: Emergence, evolution and future research. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship. Now Publishers Inc., 12, 163–285. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000063.

Westhead, P., Ucbasaran, D., & Wright, M. (2003). Differences between private firms owned by novice, serial and portfolio entrepreneurs: Impications for policy makers and practitioners. Regional Studies, 37(2), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340022000057488.

Williams, T. A., Thorgren, S., & Lindh, I. (2019). Rising from failure, staying down, or more of the same? An inductive study of entrepreneurial reentry. Academy of Management Discoveries. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2018.0047.

Yamakawa, Y., Peng, M. W., & Deeds, D. L. (2015). Rising from the ashes: Cognitive determinants of venture growth after entrepreneurial failure. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 39(2), 209–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12047.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5).

Zacharakis, A. L., & Meyer, G. D. (1999). Differing perceptions of new venture failure: A matched exploratory study of venture capitalists and entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 37(3), 1–14 Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/openview/2a5468adabf749154bc46a47e6deb034/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=49244.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that contributed substantially to the development of the manuscript. We also appreciate the participants in our interviews. Authors also acknowledge the financial support received by the Regional Productive Committee- CORFO [16PAER-61898].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guerrero, M., Espinoza-Benavides, J. Do emerging ecosystems and individual capitals matter in entrepreneurial re-entry’ quality and speed?. Int Entrep Manag J 17, 1131–1158 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00733-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00733-3