Abstract

Purpose

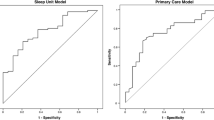

Identification of risk for continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP) nonadherence prior to home treatment is an opportunity to deliver targeted adherence interventions. Study objectives included the following: (1) test a risk screening questionnaire to prospectively identify CPAP nonadherence risk among adults with newly diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), (2) reduce the questionnaire to a minimum item set that effectively identifies 1-month CPAP nonadherence, and (3) examine the diagnostic utility of the screening index.

Methods

A prospective, longitudinal study at two clinical sleep centers in the USA included adults with newly diagnosed OSA (n = 97; AHI ≥5 events/h) by polysomnogram (PSG) consecutively recruited to participate. After baseline participant and OSA characteristics were collected, a risk screening questionnaire was administered immediately following CPAP titration polysomnogram. One-month objective CPAP use was collected.

Results

Predominantly, white (87 %), males (55 %), and females (45 %) with obesity (BMI 38.3 kg/m2; SD 9.3) and severe OSA (AHI 36.8; SD 19.7) were included. One-month CPAP use was 4.25 h/night (SD 2.35). Nineteen questionnaire items (I-NAP) reliably identified nonadherers defined at <4 h/night CPAP use (Wald X 2[8] = 34.67, p < 0.0001) with ROC AUC 0.83 (95 % CI 0.74–0.91). Optimal score cut point for the I-NAP screening questionnaire were determined to maximize sensitivity (87 %) while maintaining specificity >60 % (63 %).

Conclusion

A risk screening questionnaire employed immediately after titration PSG may reliably identify CPAP nonadherers and permit the delivery of targeted interventions to prevent or reduce nonadherence. This novel approach may enhance cost-effectiveness of care and permit appropriate allocation of resources for CPAP adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kushida CA et al (2006) Practice parameters for the use of continuous and bilevel positive airway pressure devices to treat adult patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Sleep 29:375–380

Gay P et al (2006) Evaluation of positive airway pressure treatment for sleep related breathing disorders in adults. Sleep 29:381–401

Sawyer AM et al (2011) A systematic review of CPAP adherence across age groups: clinical and empiric insights for developing CPAP adherence interventions. Sleep Med Rev 15:343–356

Weaver TE, Grunstein RR (2008) Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5:173–178

McArdle N et al (1999) Long-term use of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159:1108–1114

Weaver TE et al (1997) Night-to-night variability in CPAP use over first three months of treatment. Sleep 20:278–283

Aloia MS et al (2007) How early in treatment is PAP adherence established? Revisiting night-to-night variability. Behav Sleep Med 5:229–240

Budhiraja R et al (2007) Early CPAP use identifies subsequent adherence to CPAP therapy. Sleep 30:320–324

Crawford MR et al (2013) Integrating psychology and medicine in CPAP adherence—new concepts? Sleep Med Rev. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.002

Lewis K et al (2004) Early predictors of CPAP use for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 27:134–138

Baron K et al (2011) Spousal involvement in CPAP adherence among patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 15:525–534

Sawyer A et al (2011) Do cognitive perceptions influence CPAP use? Patient Educ Couns 85:85–91

Stepnowsky CJ et al (2002) Psychologic correlates of compliance with continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep 25:758–762

Baron K et al (2011) Self-efficacy contributes to individual differences in subjective improvements using CPAP. Sleep Breath 15:599–606

Aloia MS et al (2005) Predicting treatment adherence in obstructive sleep apnea using principles of behavior change. J Clin Sleep Med 1:346–353

Drake CL et al (2003) Sleep during titration predicts continuous positive airway pressure compliance. Sleep 26:308–311

Iber C et al (2007) The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Westchester

Johns MW (1993) Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea. The Epworth sleepiness scale. Chest 103:30–36

Weaver TE et al (1997) An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep 20:835–843

Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ (2004) Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 36:588–594

Weaver TE et al (2003) Self-efficacy in sleep apnea: instrument development and patient perceptions of obstructive sleep apnea risk, treatment benefit, and volition to use continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep 26:727–732

Wilson JMG, Junger G (1968) Principles and practice of screening for disease, in Public Health Papers. World Health Organization, Geneva

Sawyer AM et al (2010) Differences in perceptions of the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure therapy among adherers and nonadherers. Qual Health Res 20:873–892

Balachandran JS et al (2013) A brief survey of patients’ first impression after CPAP titration predicts future CPAP adherence: a pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med 9:199–205

Ghosh D, Allgar V, Elliott MW (2013) Identifying poor compliance with CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea: a simple prediction equation using data after a two week trial. Respir Med 107:936–942

Tan MCY et al (2008) Cost-effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea in British Columbia. Can Respir J 15:159–165

Guest JF et al (2008) Cost-effectiveness of using continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of severe obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnoea syndrome in the UK. Thorax 63:860–865

Ayas NT et al (2006) Cost-effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure therapy for moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea. Arch Intern Med 166:977–984

Epstein LJ et al (2009) Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 5:263–276

Stepnowsky CJ, Marler MR, Ancoli-Israel S (2002) Determinants of nasal CPAP compliance. Sleep Medicine 3:239–247

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Grant Numbers R00NR011173 and K99NR011173 from the National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge the sleep center staff members and providers who supported research recruitment, enrollment, and protocol procedures at the respective centers and early consultation with Greg Maislin, Biomedical Statistical Consulting and Judy A. Shea, PhD, University of Pennsylvania.

Conflict of interest

Drs. King, Hanlon, Sweer, and Rizzo disclose no conflicts of interest. Dr. Sawyer has received funding from National Institutes of Health/NINR, American Nurses Foundation and Sigma Theta Tau International and has received honoraria as an educational speaker for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Dr. Weaver discloses the following: Research equipment support from Philips Respironics, Inc.; Grant support from TEVA, Inc. (2008–13); FOSQ License Agreements with Nova Som, GlaxoSmithKline, Philips Respironics, Cephalon, Inc., and Nova Nordsk; and serves on the Board of Directors for ViMedicus, Inc. Dr. Weaver also has received research support from National Institutes of Health. Dr. Richards has received research support from Philips Respironics, Inc., National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sawyer, A.M., King, T.S., Hanlon, A. et al. Risk assessment for CPAP nonadherence in adults with newly diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea: preliminary testing of the Index for Nonadherence to PAP (I-NAP). Sleep Breath 18, 875–883 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-014-0959-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-014-0959-z