Abstract

Management and organization scholars have long been intrigued by the performing arts—music, theater, and dance—as a rich context for studying organizational phenomena. Indeed, a plethora of studies suggest that the performing arts are more than an interesting sideline for authors, as they offer unique theoretical and empirical lenses for organization studies. However, this stream of literature spreads across multiple research areas, varies with regard to its underlying theories and methods, and fails to pay sufficient attention to the contextuality of the findings. We address the resulting limitations by identifying and reviewing 89 articles on management and organization related to the performing arts published in 15 top-tier journals between 1976 and 2022. We find that research in the performing arts advances organizational theory and the understanding of organizational phenomena in four key ways, namely by studying (1) organizational phenomena in performing-arts contexts; (2) performing-arts phenomena in organizational contexts; (3) organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts theories; and (4) organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts practices. We also find that, in contrast to other settings, the performing arts are uniquely suited for immersive participant-observer research and for generating genuine insights into fundamental organizational structures and processes that are generic conditions of the performing arts and management alike, such as leadership, innovation, and the management of uncertainty. Finally, based on our consolidation of the research gaps and limitations of the reviewed studies, we develop a comprehensive agenda for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past thirty years, management scholars have increasingly sought to investigate organizational phenomena in the context of the performing arts—music, theater, and dance (Berniker 1998; Harrison and Rouse 2014; Kramer and Crespy 2011; Ladkin 2008; Stephens 2021). For example, Murnighan and Conlon (1991) illuminate trade-offs between leadership and democracy in string quartets; Glynn and Lounsbury (2005) investigate institutional and discursive change in symphony orchestras; and other well-known studies use theater and music to explore innovation, creativity, and transformation (Berg 2016; Cancellieri et al. 2022; Hatch 1998; Vera and Crossan 2005). As Weick indicated, viewing the performing arts as a metaphor for organizational processes can help scholars avoid “stroking toward the white cliffs of the obvious” (1974, p. 487). Not surprisingly thus, a wide range of research leverages the performing arts as a window into (inter)actions, cognitions, and emotions in organizations and their environments.

Notably, bridging the performing arts and organizations has long been a standing tradition in both the social sciences and the arts. In the sixteenth century, “to perform” became a technical term for “acting or representing on a stage” or “sing[ing] or render[ing] on a musical instrument” (Etymonline.com 2020). Since the mid-twentieth century, sociologists have increasingly referred to dramaturgy and theater as valid metaphorical source domains to conceptualize and elucidate the hidden theatrical structure of individual and collective behavior (Bourdieu 1990; Feldman and Pentland 2003; Mangham 1986; Pentland and Rueter 1994). Goffman, for instance, used the term “performance” to denote “all activity of an individual which occurs during a period marked by his continuous presence before a particular set of observers and which has some influence on the observers” (1959, p. 22).

Ever since social scientists established a direct semantic and conceptual connection between the performing arts and performance in organizations, an array of studies have demonstrated that management, innovation, leadership, and other organizational phenomena have much in common with such activities as performing, directing, choreographing, and conducting (Mangham 1990). Particularly, scholarly interest rose as Organization Science published a special issue on jazz improvisation and organization theory in 1998 (Lewin 1998; Weick 1998). This stream of literature has generated rich counter-conventional insights, and scholars continue to debate how they can best apply the vantage point of the performing arts as a prism for understanding issues in organizations (Biehl-Missal 2011; Cornelissen 2004).

Practitioner-oriented publications advising to use the performing arts as a source of new solutions to pivotal managerial challenges have also increased significantly (Clarkeson 1990; Conforto et al. 2016; Kao 1996). For example, in “Managing as Performing Art,” Vaill (1989) argues that instead of increasing managerial comprehension and control, managers should embrace paradox and equip themselves with new techniques and options for dealing with uncontrollability and chaos. Meanwhile, companies increasingly seek performing artists, including conductors, musicians, and members of theater companies, to inject knowledge from the performing arts into their organizations (Furu 2012; Hunt et al. 2004). For instance, the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra successfully facilitates its conductor-less “Orpheus process” to executives and consultancies (Orpheus Chamber Orchestra 2020). World-famous conductors, such as Herbert Blomstedt, Riccardo Chailly, and Sir Roger Norrington, share their experiences in conducting large ensembles with executives in the “Management Symphony,” a series of orchestra workshops designed for managers held at Leipzig’s Gewandhaus (Orchesterstiftung der Deutschen Wirtschaft 2020).

Perhaps because of organizational research’s growing interest in the performing arts, the organizational scholarly literature in this regard has spread across multiple research areas and varies substantially as to the underlying theories and methods. Indeed, this literature remains highly fragmented as it relates to the types of performing arts considered, the function of performing-arts-related theories and empirics, and its main contributions and insights. While such multifacetedness can be a source of explanatory power and narrative appeal, fragmentation limits the potential of this research stream to advance organizational science. Fragmentation and lack of synthesis also undermine a fruitful critique of this literature. This seems to be important in light of criticism, for example, against an overly simplistic, naïve portrayal of ‘great’ orchestra conductors and the idealization of the leadership of highly motivated, skilled, and creative people (Hunt et al. 2004).

Our systematic literature review (Fisch and Block 2018) seeks to address these issues by pursuing three main objectives. First, we aim to map the theories and models used to organize the rather fragmented literature. Second, we adopt a critical perspective on the aptness of the performing arts as a metaphorical source domain for studies of organizational issues (Thibodeau and Boroditsky 2011). Third, we seek to outline promising avenues for future research. In these quests, we followed established procedures in the field (Tranfield et al. 2003) and screened 37 scientific top-journals from the field of organization and management science to select, read, and inductively integrate 89 peer-reviewed articles. In particular, using recent approaches on conceptual metaphors in organization science (Cornelissen 2005, 2006; Lakoff and Johnson 1980) and idiosyncrasies in cross-contextual research (Whetten 1989, 2009) as our taxonomical guideposts, we organize the literature in four broader categories: (1) research that studies organizational phenomena in performing-arts contexts; (2) research that studies performing-arts phenomena in organizational contexts; (3) research that views organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts theories; and (4) research that views organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts practices.

We offer three major contributions. First, our induced conceptual framework of the literature broadens the focus from singular phenomena highlighted in prior reviews, such as organizational improvisation (Hadida et al. 2015; Pina e Cunha et al. 1999), towards a general perspective on organizational research in the context of the performing arts. Second, we demonstrate how and why research in the context of the performing arts can be particularly valuable to organization and management theory. In particular, both contexts face similar challenges in terms of timing (Albert and Bell 2002), coordination (Harrison and Rouse 2014), leadership (Hunt et al. 2004), creativity (Berg 2016), and innovation (Kamoche and Pina e Cunha 2001). As such, scholarly conversations on these phenomena are the ones that are most richly and validly informed by organizational literature in the context of the performing arts (Cohen et al. 1996). As we outline, this is especially true in times of instability and uncertainty (Vaill 1989). Third, we enhance prior scholarship that has highlighted the specificities of organizational research in idiosyncratic empirical contexts (Hällgren et al. 2018). In particular, whereas scholars have explained the intricacies of sports as an empirical background (Day et al. 2012), we delineate the opportunities and limitations of the performing arts as an alternative research context for organization scholars. Altogether, by organizing knowledge gained from the cross-fertilization of the performing arts and organization science, we respond to recent calls for more context-sensitive organizational research and counterfactual reasoning (Whetten 2009).

2 Research method

In line with established procedures (Booth et al. 2016; Fisch and Block 2018; Tranfield et al. 2003), we highlight three aspects as to the scope of our review and the relevance of the selected literature. First, we focused on theories stemming from the performing arts or empirical data directly related to performing-arts practices. That is, we excluded accounts that frame organizations as, for instance, “social drama” (Rosen 1985, p. 31) or leadership as an art (Conger 1989) but lack any concrete theoretical or empirical reference to the performing arts. Second, in line with our theoretical orientation, we only investigated papers concerned with the performing arts in the sense of “types of art (such as music, dance, or drama) that are performed for an audience” (Merriam-Webster.com 2020). Therefore, we excluded studies that focus on types of art that are not performed in front of an audience, such as movies and recorded music.Footnote 1 Third, as we are interested in management and organizational issues, we excluded studies from the fields of marketing, (occupational) psychology, and economics. Moreover, while we acknowledge that other disciplines, such as communication studies, musicology, theater studies, and cultural studies, provide valuable insights regarding the performing arts and their implications for management-related topics, we decided to select those journals that are most relevant for management and organization scholars.

Specifically, to focus our literature review on the most relevant results for organizational research, we centered our search on top-tier outlets from the fields of management, organization, innovation, and entrepreneurship. In this vein and consistent with recent literature reviews in this field (e.g., Graf-Vlachy et al. 2020; Gutmann 2019), we used the VHB JOURQUAL 3 expert-survey ranking of the German Academic Association for Business Research to identify all journals rated A or A+.Footnote 2 As shown in Harzing (2020), this ranking identifies the most renowned, high-quality journals quasi-identically to other international journal rankings, such as the Chartered Association of Business Schools or the Financial Times rankings. We considered each journal rated A or A+ from the VHB JOURQUAL 3 sub-ratings business administration, organization, human resource management, international management, strategic management, technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship. In total, we considered 37 scientific journals. Table 1 shows the number of articles in the sample classified by journal.

We followed a structured content-analysis process involving three stages—sampling, coding, and analysis (Duriau et al. 2007)—to inductively identify key themes. First, we utilized a keyword search to develop our sample (Krippendorff 2013). We used the EBSCO database to search for the following keywords and their respective word stems, as indicated by the Boolean asterisc operators, in the title or abstract of the articles: ballet, circus, dance, drama*, jazz, music*, opera, orchestra, performing arts, and theat*. After screening the abstracts of the 257 identified papers, we excluded all papers that did not match the scope of this review, which yielded a sample of 108 articles. After that, we removed 29 articles when a full reading suggested they were outside our research scope. Moreover, following Graf-Vlachy et al. (2020), we identified ten relevant articles through backward and forward searches (excluding books, chapters, and journals not A/A+ ranked). The final sample included 89 peer-reviewed articles published in 15 journals, as depicted in Table 1.

Second, we coded the articles in our final sample. To do so, we developed a codebook containing different types of codes (Krippendorff 2013). The preliminary set of codes included nominal variables, such as type of data or methods, and qualitative categories, such as the paper’s key contributions or theoretical conversations to which the paper contributed.

Third, we iterated between the purely inductive coding (Gioia et al. 2013; Glaser and Strauss 1980) described in stage two and searching for suitable existing categorizations and constructs in the literature. Consequently, we arrived at a research framework for categorizing our sample along two dimensions, namely, first, the role of performing arts as empirical and/or conceptual source domain, and, second, the approach to making a theoretical contribution. We explain this research framework and its interpretation in the “Research framework” section.

3 Descriptive overview of the relevant literature

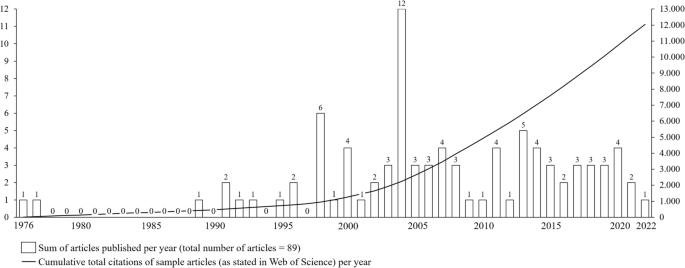

Figure 1 shows the distribution and cumulative citations of sample articles per year. The articles in the sample were published between 1976 and 2022. Positive outliers in the number of articles per year arise from the publication of special issues of Organization Science in 1998 and Organization Studies in 2004.

In terms of their methodology, most of the studies are empirical (74%), with 60% thereof relying on qualitative methods, 25% on quantitative methods, and 15% on mixed methods. Most articles draw on the context of drama or theater, followed by music and dance. Few relate to other contexts, such as stand-up comedy, circuses, or festivals. A Web of Science search for citations of the sampled articles revealed that research in the context of the performing arts is of increasing interest to organization scholars, as depicted in Fig. 1.

In the period 1976 to 2022, the sampled articles have cumulatively received nearly 12,000 citations.Footnote 3 As shown in Fig. 1, interest started to increase significantly in the late 1990s. Notably, the cumulative annual citations of the articles in our sample have been growing by about 350 citations on average per year since 1999. In comparison, the average annual citation growth of all papers published in the journals in our sample during the same time span was only 76 citations.Footnote 4 This over-proportional growth in interest in the sample articles seems to support the idea that organization scholars are indeed interested strongly in investigations in the performing arts context. Table 2 presents the most widely cited articles in the sample as measured by average annual Web of Science citations. Five articles—Grandey (2003), Maitlis (2005), Voss et al. (2008), Goldin and Rouse (2000), and Maitlis and Lawrence (2007)—have achieved mean annual citation counts between 25 and 57, well above the sample average of 13.

4 Research framework

Table 3 shows the first outcome of our coding exercise—the categorization of the reviewed articles into four groups along two dimensions. As the first dimension, on the horizontal axis, we categorized the articles according to the role of performing arts as empirical and/or conceptual source domain for the organizational structures and processes under investigation. We induced this dimension from the frequency with which the notion of ‘performing arts as a metaphor for organizational phenomena’ (e.g., Lewin 1998; Weick 1998) surfaced in the sampled literature. At the heart of a metaphor is the description or understanding of a rather complex and unfamiliar concept A—i.e., the target domain—through the frame of a simpler, more familiar concept B—i.e., the source domain (Cornelissen 2005, 2006; Lakoff and Johnson 1980). In this vein, we split the sample into studies in which the performing arts are the primary source domain for the organizational structures and processes under investigation, and studies in which the performing arts are a secondary source domain for the organizational structures and processes under investigation.

Specifically, we categorized any given paper as performing arts are the primary source domain if the authors observed or analyzed phenomena in a performing arts context. For example, studies that primarily used data from and/or ideas about symphony orchestras, jazz combos, opera houses, or improvisation techniques to investigate organizational phenomena fall in this category. Conversely, we allocated a paper to the category of performing arts are a secondary source domain if it drew from contexts that are merely indirectly related to the performing arts. For example, studies that analyzed theater performances within otherwise not performing-arts-related organizations fall into this category. This categorization was useful as the performing arts as primary context category identifies studies that might be directly associated with the theme of our review, while the performing arts as secondary source domain category highlights the ubiquity of more latent but equally rich applications of (concepts from) the performing arts in organizational research.

As the second dimension, on the vertical axis, we categorized the literature depending on the respective approach to making a theoretical contribution—namely, as either uses observation to inform theory or uses theory to inform observation. This category builds on Whetten’s (2009) differentiation between two—equally valuable—ways of creating novel and interesting theoretical contributions from context-spanning research: first, “theory improvement,” (Whetten 2009, p. 35), where research in a foreign context allows scholars to develop contributions to theory in a focal discipline; and second, “theory application,” (Whetten 2009, p. 35) where an established theoretical framework from a foreign epistemic context or discipline is used to better understand a phenomenon in a focal discipline (Whetten 2002, 2009). In this vein, for example, we categorized papers that collected data from music competitions to advance theory on the influence of auditive versus visual cues on decision-making (Goldin and Rouse 2000; Tsay 2014) as uses observation to inform theory. In contrast, for example, we categorized papers that analyzed organizational crisis through the lens of music theory (e.g., Albert and Bell 2002) as uses theory to inform observation. Whetten’s (2009) categorization scheme proved particularly helpful because it directly matches the inherently cross-contextual overall logic of our review. It also allows us to highlight that the performing arts provide an interesting empirical context and encompass a broad and rich epistemic tradition and conceptual reservoir.

Taken together, our two conceptual dimensions generated a two-by-two matrix that allowed us to cluster the literature into four categories, as depicted in Table 3. We labeled the quadrants as follows: (1) “advancing organizational theory by studying organizational phenomena in performing-arts contexts” (‘performing arts as primary source domain’ and ‘uses observation to inform theory’—47 studies); (2) “advancing organizational theory by studying performing-arts phenomena in organizational contexts” (‘performing arts as secondary source domain’ and ‘uses observation to inform theory’—10 studies); (3) “understanding organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts theories” (‘performing arts as secondary source domain’ and ‘uses theory to inform observation’—19 studies); and (4) “understanding organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts practices” (‘performing arts as primary source domain’ and ‘uses theory to inform observation’—13 studies). In addition, for the sake of taxonomic order and comprehensibility, we further categorized all studies within each quadrant according to the major topics of two divisions of the Academy of Management that seemed closest to the papers’ central contributions: Managerial and Organizational Cognition (MOC), and Organizational Behavior (OB).Footnote 5 This deductive exercise prompted us to categorize studies in quadrants one, two, and four using selected topics of the MOC division and studies in quadrant three using selected topics of the OB division.Footnote 6 We provide a more detailed overview of the selected studies in the Appendix.

Below, we elaborate on the key theoretical contributions of the papers in each quadrant. Following Alvesson and Sandberg’s (2020) approach, which suggests a rather selective but detailed description of the field of research in a literature review, we focus on the most cited and what appeared to us as the most representative studies.

4.1 Quadrant 1: advancing organizational theory by studying organizational phenomena in performing-arts contexts

Quit studying [corporate] organizations [—study organizations] elsewhere.

(Weick 1974, p. 487)

All studies in this category aim to inform organizational theory by observing and analyzing organizational phenomena in the context of the performing arts. Table 3 shows that most studies in our sample (47 papers; 52 percent of the sample) fall into this category. Generally, the authors of these studies followed Weick’s (1974) recommendation to test accepted assumptions and hypotheses in different contexts until organizational theories are valid approximations of reality (Weick 1995). Research in this category predominantly offers theoretical contributions to four scholarly conversations highlighted by the AOM’s MOC division: (social) identity (e.g., Hales et al. 2021; Hunt et al. 2004; Kim and Jensen 2011; Voss et al. 2006), social construction (e.g., Ladkin 2008; Riza and Heller 2015; Sagiv et al. 2019; Stephens 2021; Toraldo et al. 2019), judgment and decision making (e.g., Cattani et al. 2013; Goldin and Rouse 2000; Tsay 2014), and communities of practice (e.g., Eikhof and Haunschild 2007; Harrison and Rouse 2014; Kramer and Crespy 2011).

4.1.1 Contributions to the conversation on “(social) identity”

The studies in this category leverage the fact that values, identity perceptions, and related institutions are particularly salient among performing artists and stakeholders of performing-arts organizations (Kim and Jensen 2011; Voss et al. 2006). Performing artists, such as musicians or dancers, often profoundly identify with their profession and strongly socially identify with their organizations, such as their orchestra or dance ensemble (Hunt et al. 2004; Riza and Heller 2015). Moreover, by design, members of and leaders in performing-arts organizations need to deal with the endemic paradox of contradictory but interdependent artistic and economic logics, many of which are tied to profound identity perceptions (Eikhof and Haunschild 2007; Parker 2011; Shymko and Roulet 2017; Voss et al. 2000).

As such, the works in this category aim to develop an understanding of core organizational values and identities as well as their emergence and implications (Jensen and Kim 2014). Glynn (2000), for example, studies the 1996 musician strike at the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra to address the challenges leaders face in reconciling conflicting organizational identity perceptions among organizational members. Specifically, she describes how musicians identified with the objective of artistic excellence and how that identification clashed with administrators’ goals of allocating resources in ways that seemed economically helpful. From her observations, Glynn induces a model that shows how the process of identifying core competencies becomes contested, “nonlinear, nonrational, and socially constructed” (2000, p. 286) because of conflicting identities and related norms and values. This model stood in notable contrast to the notion of capability construction held among scholars at the time of the study.

Other studies investigate related phenomena in other performing-arts contexts. Parker, for example, studies “the circus as an institutionalized questioning of forms of stability and classification” (2011, p. 555) to describe the paradoxically related institutions of spatially mobile, but at the same time excessive and stable, organizations. Intriguingly, these organizations need to ‘keep things moving’ while simultaneously hiding that mobility to preserve the illusion of magic. As another example, Hales et al. (2021) ethnographically tap into the—potentially “dark”—context of the lap dancing industry to understand how individuals and their bodies are materialized in organizational settings and how organizations themselves are determined through complex sensory processes. The authors find that organizations come into being through the three interrelated processes of encoding, embodying, and embedding. Relatedly, Voss et al. (2000) study organizational values that characterize firms in the nonprofit professional theater industry and how those values influence firms’ relationships with external stakeholders. Using grounded research methods and a two-wave survey of 97 nonprofit theaters, they find that theaters striving for publicly recognized excellence receive higher revenues from external constituents than theaters scoring high in artistic values. In other words, organizations need to adapt their external communication in ways that may contradict their deeply held norms and values to acquire economic resources. Furthermore, in their study of Russian theaters, Shymko and Roulet (2017) find that, apart from being providers of economic resources, external constituents are important for ensuring organizations’ social capital. Specifically, the authors identify the paradox that theaters need external donors to ensure the quality of their product, but simultaneously risk losing legitimacy as ascribed by their peers because of those corporate donors. Shymko and Roulet (2017) suggest that theaters (and organizations, for that matter) address that dilemma by limiting the pervasiveness, longevity, and negative salience of relationships with external stakeholders.

We also categorized studies that illuminate the performing arts to understand perceptions of status as belonging to this conversation. Two of these studies—Prato et al. (2019) and Durand and Kremp (2016)—use symphony orchestras’ programming decisions to investigate how status perceptions create a boundary condition for the middle-status conformity hypotheses, i.e., the idea that middle-status organizations deviate less from norms than low- or high-status organizations (Phillips and Zuckerman 2001). Decisions regarding whether to conform with or deviate from institutionalized norms of composer and composition selection is at the discretion of the musical director or chief conductor. Frederick Stock, for example, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Music Director from 1905 to 1942, was known for spending “endless time pondering over the problem of program-making” (Ewen 1943, pp. 133–134). Thus, chief conductors’ discretion in program-making provides a unique opportunity to isolate the status of decision-makers and its effects on the (dis)conformity of organizational behavior.

In this vein, Prato et al. (2019) analyze programming decisions made by the chief conductors of the 27 largest symphony orchestras in the US from 1918 to 1969 to uncover the conditions that shape dispositions toward conformity. The authors find that it is necessary to distinguish between achieved status and ascribed status (i.e., the status actors receive based on individual achievements versus the status they receive because of, for example, their nationality or gender). Within the group of conductors with high ascribed status (i.e., German or Austrian), the middle-status conformity hypothesis holds true. In other words, conductors with a middle level of achieved status were more likely to present a repertoire of canonical composers (e.g., Bach, Beethoven, Mozart) than a repertoire of unconventional composers (e.g., Moszkowski, Bartók) than those with high or low levels of achieved status. In contrast, among conductors with low ascribed status (i.e., non-German or non-Austrian), conductors with a middle level of achieved status were more likely to deviate than conductors with high or low levels of achieved status.

Relatedly, Durand and Kremp (2016) investigate the development of the concert programs of major U.S. symphony orchestras between 1879 and 1969 to differentiate between two forms of conformity—alignment and conventionality—and their relation to the respective status of organizations and their leaders. The authors consider an orchestra to exhibit alignment when it performs a repertoire similar to the programming of the other orchestras in a given season. Conversely, an orchestra exhibits conventionality when it focuses on highly salient and emblematic composers. Durand and Kremp (2016) find that norms and expectations lead middle-status organizations toward more alignment but middle-status individual leaders toward more conventionality than their respective low- and high-status peers. In addition, the relationship between middle-status conductors and the conventionality of their programming decisions is weaker the higher the orchestra’s status or alignment.

Taking a somewhat different tack, Innis (2022) analyzes how deviating from conventional practices can stimulate category gatekeepers, such as music critics, to redefine and even change category boundaries and meanings. In this quest, the author gathers and analyzes a corpus of reviews of jazz records between 1968 and 1975. In the late 1960s, there was a shift in the category of jazz music towards a fusion with other music styles and instruments. By 1975, the practices considered part of the jazz category had expanded considerably (Fellezs 2011). The author offers a process model that shows how category gatekeepers, i.e., jazz critics, interpret deviating practices by rearranging their evaluation criteria, and maintaining the coherence of the core meanings of the jazz category.

4.1.2 Contributions to the conversation on “social construction”

Another group of studies examines how creative workers socially construct meaningfulness and try to reconcile meaningfulness with the economic instrumentality of work. Riza and Heller (2015) approach this topic from the perspective of calling, i.e., experiencing one’s work as highly meaningful (Pratt and Ashforth 2003). The authors trace the professional development of 405 young amateur musicians over time. They find that those musicians who perceived music as a calling early in their lives did not perceive their musical abilities more favorably but were more likely to launch a career as a professional musician. In other words, perceptions of calling lead amateur musicians to opt for meaningfulness rather than an economic focus in their professional lives. Intriguingly, as Eikhof and Haunschild (2007) find in their study of creativity and business practices in German theaters, economic logics tend to crowd out artistic logics over time. This process is particularly problematic as artistic motivation is a vital resource for creative production, and, in turn, its marketability. There are no standardized routines in human resource management to deal with this economics/artistry paradox, and the pressure to master the paradox lies entirely with individuals.

Another prominent topic is the social construction of aesthetics. Barnard, for example, encourages organizational scholars to frame the process of organization as “a matter of art rather than science,” as it is, in his view, an “aesthetic rather than logical” (1983, p. 235) endeavor. In this vein, studies examine how conductors and musical leaders construct aesthetic leadership via their physical and artistic practices. Specifically, Ladkin studies a performance of vocal artist and conductor Bobby McFerrin with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra at the Proms. This leads her to lay out the aesthetic concept of leading “beautifully” (2008, p. 31)—defined as a mix of mastery, congruence, and purpose—and to argue that such leadership is particularly relevant during creative processes.

However, construals related to aesthetics also seem to influence the creative process in a broader, multi-faceted sense. In this regard, Sagiv et al. (2019) observe how 23 contemporary (i.e., highly improvisational and interdisciplinary) dance companies in Israel develop aesthetic choreographies (i.e., choreographies that are evaluated as an authentic type of artistic dance). They observe the rehearsals of these companies and conduct in-depth interviews with dancers and choreographers to induce a three-step process theory on how choreographers construct type and moral authenticity (Carroll and Wheaton 2009) through creating a new, aesthetic choreography. First, in the improvisation phase, choreographers construct moral authenticity. In other words, they signal artistic expressiveness by freely generating unstructured movements not belonging to the repertoire of, for example, classical dance. Second, in the composition phase, choreographers construct type authenticity—they justify the inclusion of the choreography in the category of artistic dance by selecting and reorganizing the movements from phase one into virtuous choreographies. Third, in the run-through phase, choreographers integrated moral authenticity and type authenticity by instructing dancers to master the technique of the movements and, simultaneously, enter an expressive dialogue with the audience.

While Sagiv et al. 2019 describe how choreographers create an aesthetic, Beyes and Steyaert use the aesthetics of defamiliarization to look at well-known “everyday sites of organizing” (2013, p. 1445) in order to create something new. They present the concept of the “aesthetics of the uncanny” (Beyes and Steyaert 2013, p. 1445) based on Brecht’s Verfremdung (“alienation”) and Freud’s das Unheimliche (“the uncanny”) (Cixous 1976). Both concepts describe audiences’ feelings of unease and alienation when presented with the familiar becoming estranged (Doherty 2007). The authors empirically illustrate their theorizing with an urban intervention in the streets of Berlin called “50 Kilometres of Files—A Walkable Stasi Radio Play” by the theater collective Rimini Protokoll.Footnote 7 This interactive performance independently navigated participants through various streets of central Berlin while playing original recordings of witnesses and describing events that happened in those places during the East German regime. The authors conclude that organizational scholars should view their research as an affective, spatial, and performative intervention that does not simply describe the world but also creates it.

In a related quest to disentangle the effects of aesthetic experiences on group performance, Stephens (2021) conducts an 18-month ethnographic study as a singer-member in a community choir. The author proposes a process model as to how choir members continuously oscillate between an aesthetic experience of fragmentation and an aesthetic experience of wholeness. The experience of fragmentation aroused negative emotions among group members, spurring them to redirect their attention and adapt their behavior. Ultimately, by increasing their focus on the musical score, the conductor, and the singers’ contributions, the group coordinated successfully towards restoring an aesthetic of wholeness.

4.1.3 Contributions to the conversation on “judgment and decision making”

Another area of interest for studies in quadrant one is how audiences judge performance and their level of creativity, authenticity, or artistry. For example, Tsay (2014) observes how 1062 expert and novice raters across six studies evaluate orchestras in live ensemble competitions based on video recordings without sound, sound recordings without video, or complete recordings. Interestingly, counter to the widespread assumption that sound is the utmost goal of professional music ensembles (Murnighan and Conlon 1991), raters predominantly rely on visual rather than auditive information (Tsay 2013). When raters are asked to distinguish the winner of each competition and rank each orchestra, their judgments based on visible group dynamics are a better predictor than their judgments based on purely auditive information or auditive and visual information together. Relatedly, Tskhay et al. (2014) analyze 51 YouTube videos of conductors leading an orchestra with a focus on implicit leadership prototypes (i.e., how validly leadership prototypes predict the actual success of conductors). Independent groups of raters evaluate the videos in terms of music parameters and in terms of how famous, expressive, old, skilled, fast, and experienced the conductor is. Surprisingly, perceivers can accurately predict conductors’ success, and they base their judgment of success predominantly on conductors’ expressiveness and age. In other words, as implicit leadership theory suggests, perceived expressiveness and age correlate with perceived conductor success, which, in turn, predicts conductors’ actual success.

Visual judgment seems to drive not only the general evaluation of artists but also decisions regarding which artists to hire. In this regard, Goldin and Rouse (2000) collect a sample of auditions submitted to eight symphony orchestras between the late 1950s through 1995 as well as the results of the respective audition processes. They analyze the impact of blind auditions (i.e., auditions in which the applicants’ gender and identity are hidden) and find that blind auditions explain up to 25% of the increase of women in symphony orchestras since the 1950s.

However, not every judgment in the performing arts is about a ‘book’s cover.’ Han and Ravid (2020) set out to assess the value of highly qualified personnel to organizations. To do so, they compile a sample of 215 Broadway shows opened between 1990 and 2013 that included changes in their casts. By comparing revenues, capacity, and ticket prices before and after a “star turnover” (Han and Ravid 2020, p. 1), they assess the actual value of human capital for each show. They differentiate among different types of stars (i.e., renowned theatre stars and celebrities). The authors find that while decorated theatre stars significantly and positively affect the financial success of Broadway shows, celebrities and movie stars fail to have such an effect. All in all, for human capital to be of value to the (creative) organization, relevant talent and skills seem to be more critical than pure visibility.

Studies in this quadrant also analyze how evaluation criteria for creative products evolve and affect knowledge creation (Cattani et al. 2013; Glynn and Lounsbury 2005). Cattani et al. (2013), for instance, analyze the unique craftmanship necessary to produce Cremonese string instruments and how their ascribed value changed over time. Based on an analysis of archival and interview data, the authors find a significant time delay between the production of string instruments made by Cremonese masters such as Stradivari and Guarneri starting in the sixteenth century and their recognition as the instruments most suitable for performing Romantic era music in the nineteenth century. This delay between production and recognition led to the loss of the tacit knowledge needed to produce comparable instruments, ultimately leading to ever-increasing product values over time.Footnote 8 This process could explain why, even though present-day luthiers claim to be able to reproduce the quality of Cremonese masters, only the originals fetch auction prices in the millions of dollars, such as the Lady Blunt Stradivarius, which was sold for USD 15.9 million in 2011 (BBC 2011).

Studies in this quadrant discuss not only how creative products are judged but also who should judge them (Berg 2016; Marotto et al. 2007). For example, in an endeavor to analyze the conditions that help accurately predict the success of creative ideas, Berg (2016) relies on a field study in the circus-arts industry and a lab experiment. In the field study, he asks 489 individuals, including laypeople, circus artists (i.e., “creators”), circus directors, producers, and agents (i.e., “managers”), to forecast the success of online videos of circus acts. In the lab experiment, 206 participants are assigned to different conditions and asked to rank product ideas according to their presumed novelty and success with consumers. The study shows that artists, or creators, are more successful than managers in predicting the success of others’ ideas. At the same time, creators overestimate the success of their own ideas. These findings imply that idea generation and evaluation, when exclusively executed by the same person, might hamper creativity and innovation.

4.1.4 Contributions to the conversation on “communities of practice”

Another prominent theme is the depiction and analysis of theatre groups, orchestras, or string quartets as communities of practice. This term denotes the idiosyncratic habits found in performing-arts-related organizations, which makes them unique units of analysis for organizational studies (Weick 1992). For example, Kramer and Crespy (2011) study collaborative leadership practices by acting as participant-observers in a theater production. With one author serving as the play's director and one taking part as an actor, they find that the director uses specific communicative practices to make their collaborative leadership style more efficient. This includes selecting skilled, experienced, and confident theatre personnel open to collaborative leadership practices. Furthermore, the director encourages casual relationships among cast members to facilitate collaboration within the team. Notably, the leader explicitly defines the work context as collaborative, reinforces openness to shared creation, and responds positively and supportively to attempts at collaboration. Moreover, short collaboration-seeking pieces of communication, instead of prolonged discussions, were crucial, ultimately creating positive synergies within the group.

Harrison and Rouse (2014) uncover a related type of collaborative practices in their study of modern dance group rehearsals. Modern dance is particularly suited for analyses of coordination in creative group work because—in contrast to the more canonized forms of traditional dance—it emphasizes creative group actions aimed at finding novel movements (Atler 1999). The authors gather observational and interview data from four dance groups selected for a 10-week review process to possibly perform in a tri-annual concert. They uncover three aggregate dimensions that describe the types of interaction patterns occurring during a rehearsal: “surfacing boundaries,” “discovering discontinuities,” and “parsing solutions” (Harrison and Rouse 2014, p. 1265). When starting to improvise, dancers actively seek constraints from the choreographer by asking detailed questions. In the next stage, dancers highlight problems or propose options, engaging the entire dance group in a dialogue. In the last stage, dancers attempt to find a suitable solution through negotiations, which also means they willingly limit their autonomy.

Instead of focusing on emerging coordination in groups, Chiles et al. (2004) explain the emergence of new organizational collectives using the case of live musical performance theaters in Branson, Missouri. Over a single century, this small town evolved from a remote area of the Ozarks into the second most popular road-trip destination in the US, with more than six million tourists visiting its live theaters every year. The authors collect interviews, observational data, and archival data, and describe the evolution of Branson between 1895 and 1995. They find four dynamics that explain this phenomenon. First, spontaneous fluctuations, such as a famous novel praising Branson’s natural beauty and the connection to the national rail line, started a new social order. Second, positive feedback loops, such as improved highway infrastructure and communal marketing organizations, corroborated these fluctuations. Third, stabilizing mechanisms, such as government enforcement of Branson’s bible belt culture, underpinned the emerging order. Fourth, successful ventures left their facilities to build larger theaters, while failed theaters left their facilities empty. This dynamic recombined the elements existing in the Branson collective, leaving vacant facilities available to new entrepreneurs.

Relatedly, Sgourev investigates recombination in the context of the performing arts and the effects of this kind of “brokerage” (2015, p. 343). Brokerage denotes the process of connecting social actors in order to provide access to various resources (Sgourev 2015). The author analyzes Sergej Diaghilev, the famous founder and producer of the Ballets Russes, one of the most influential ballet companies in history, whose ballets such as “Le Pavillon d’Armide,” “Les Sylphides,” and “Le Sacré du Printemps” revolutionized the arts in the beginning of the twentieth century. The author finds that Diaghilev was a catalyst for social change in the arts and in broader society because he was the first to broker between artists from different professional and cultural backgrounds, such as Coco Chanel, Claude Debussy, Vaslav Nijinsky, Pablo Picasso, and Igor Stravinsky. Diaghilev’s brokerage undermined the established social order and gave rise to the avant-garde, ultimately escalating modernism.

In a similar vein, Allmendinger and Hackman (1996) scrutinize radical environmental changes and the circumstances under which organizations eventually adapt to those changes. The authors study the impact of two political-economic changes on organizations: the spread of the socialist regime after World War II and the collapse of that regime in 1990. To do so, the authors gather longitudinal data from 78 symphony orchestras from East Germany, West Germany, the UK, and the US, including archival data, interviews with and surveys of players and managers, and observational data from visits to each orchestra. Interestingly, they find that while the arrival of socialist rules did not particularly affect orchestras, the demise of socialism triggered a wide array of reactions among orchestras, with some orchestras adapting much more successfully than others. This effect was moderated by the orchestra’s standing and its leadership such that well-financed orchestras became stronger, while weaker orchestras lost prestige and already scarce resources.

Studies in this category observe not only external shocks but also internal challenges. In this vein, Murnighan and Conlon (1991) collect archival data and interview 80 professional string-quartet musicians playing in 20 British string quartets to study internal group dynamics and how they affect the ensembles’ success. They find that players must reconcile three paradoxes: leadership versus democracy, the paradox of the second violinist, and confrontation versus compromise. As the authors conclude, the most successful quartets are aware of these paradoxes and manage them—the first violinist acts as a leader and simultaneously advocates for democracy; the second violinist accepts their secondary role and is openly appreciated by the group’s members; and group members exchange conflicting views but also drop issues at a certain point to enable the group’s progress.

While studies in this quadrant often focus on performing-arts organizations that serve as self-governing work groups, other studies focus on the more formalized aspect of performing-arts organizations. In this vein, Maitlis (2004) focuses on symphony orchestras and explores which practices chief executive officers use to influence their boards. For two years, the author gathers longitudinal data from two British symphony orchestras by attending meetings of the boards and their subcommittees, shadowing the CEO, observing rehearsals, and interviewing the CEO, managers, players, board members, and the conductor. Maitlis (2004) proposes four key processes that sustain successful CEO influence on their boards. First, a CEO who interacts frequently with the director in a trustful and open manner is more likely to exploit that relationship successfully. Second, the ability to manage the board’s impressions, especially about a CEO’s competence and legitimacy, is a crucial factor. Third, a CEO who intends to influence the board needs relevant data, which must be disseminated “just enough and at just the right times” (Maitlis 2004, p. 1299). Fourth, a CEO should be willing to take on the role and protect their formal authority instead of letting others assume a similar decision-making position.

4.2 Quadrant 2: advancing organizational theory by studying performing-arts phenomena in organizational contexts

All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.

(Jacques in Shakespeare 2009, act II, scene VII)

Studies in this category analyze performing-arts phenomena within organizations, such as the production of pieces of theater within organizations. Table 3 shows that this category is the smallest, with only 10 papers (12 percent of the sample). They all contribute to the conversation on sensemaking and sensegiving in organizations (Gioia and Chittipeddi 1991). Cronin (2008), for example, compares the sensegiving in organizations to the appearance of any person on stage. He argues that effective leaders, politicians, and actors alike connect with their audience, understand and exploit symbols, listen empathetically, improvise, and radiate confidence while projecting discipline, toughness, and honesty.

Most studies in this category focus on theater, especially on theater in organizations. This corporate theater or organizational theater is referred to as a “technology” within organizations (Clark and Mangham 2004a, p. 37) and includes directors, actors, and musicians, performing for an audience. In other words, theater pieces are performed within an organization, either by consultancies and professional actors or by organizational members who become amateur actors. The use of theater and staged performances in firms emerged about 100 years ago, when large US corporations, such as Coca-Cola and IBM, wanted to enhance their annual sales conferences with shows (Pineault 1989). In this vein, Clark and Mangham (2004a) analyze a piece of corporate theater called Your Life. Your Bank, which had been commissioned by a large bank in order to celebrate and consolidate its merger with another bank. Over a period of eight months, the authors observe meetings between the consultancy commissioned to produce the performance and firm representatives, rehearsals, and, finally, the performance in front of 5000 people. The cast primarily consisted of senior executives who had prepared and executed the merger. The stage design included the audience walking down an avenue of exhibition stands on their way to the impressive auditorium, which the authors interpret as similar to a “Roman processional route provided for a conquering general” (Clark and Mangham 2004a, p. 50). The appearance of The Corrs, one of the most successful bands at the time, and one of the best-known UK television presenters, made the audience cheer and dance. The authors find that, after attending the performance, the audience members were motivated, inspired, and felt greater pride in their new employer.

Notably, some authors take a critical stance toward these performances, as theatrical techniques are often used to seduce organizational members. In this vein, scholars criticize such forms of “visual extravaganza” (Clark and Mangham 2004a, p. 54) as a “theater of the oppressor” (Nissley et al. 2004, p. 829) that promotes a reality on stage that is convenient for senior management. In line with the Brechtian tradition of forum theater, which aims to be a “weapon for liberation” (Boal 1979, p. vi), some authors side with Brazilian director and actor Augusto Boal (1979), who views theater as a tool for activating the audience and inspiring critical reflection (Meisiek 2004).

In sum, scholars in this category argue about whether the goal of corporate theater is purely motivational (Clark and Mangham 2004a) or to represent organizational reality as contingent by speaking to the hearts and minds of the audience (Meisiek 2004). According to Schreyögg and Häpfl (2004), the goal of organizational theater is to discuss critical issues in organizational life, such as communication barriers between middle and lower management, groupthink in management meetings, sexual harassment, and workaholism. As such, organizational theater is meant to intervene in organizational development and can suggest a different perspective on problems, thereby initiating “a closer examination of habituated patterns of behavior, established perceptual constructions, and possibly prejudicial views” (Schreyögg and Häpfl 2004, p. 698).

4.3 Quadrant 3: understanding organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts theories

The great leaders have always carefully stage-managed their effects.

(Charles de Gaulle, as cited by Schoenbrun 1966, p. 91)

Studies in quadrant three apply theories from the field of the performing arts to the analysis of organizational phenomena. Quadrant three is the second-largest category, with 19 studies (22 percent of the sample). Studies in this category predominantly contribute to two topics that the AOM’s MOC division lists among its major topics of interest: perception (e.g., Albert and Bell 2002; Biehl-Missal 2011; Boje et al. 2004, 2006; Grandey 2003) and leadership (e.g., Gardner and Avolio 1998; Sinha et al. 2012; Weischer et al. 2013).

4.3.1 Contributions to the conversation on “perception”

Studies in this sub-stream of quadrant three apply performing-arts theories to perception in organizations. Albert and Bell (2002), for instance, apply music-theory principles to the case of a religious cult in Texas to understand “point-moment questions” (Albert and Bell 2002, p. 574), i.e., questions on when to act. In 1993, after weeks of fruitless negotiations, the FBI had decided to storm a compound in Waco, Texas, where they believed fanatic David Koresh to be encouraging his group of followers to commit mass suicide. The authors use theory on tonality, rhythm, musical shape, and harmony to understand the FBI’s decision to launch its assault. They conclude that the inferno that marked the end of the Waco plot line follows a linear and strongly progressive temporal structure (Kramer 1988). They suggest that the temporal dynamic could have been slowed by the troops moving back. Similarly, a change in the tonality,Footnote 9 which could have been introduced by, for instance, putting barbed wire around the compound and, thus, putting Koresh under house arrest, could have changed the meaning of elapsed time and have provided the FBI with more time to decide how and when to act.

Relatedly, Grandey (2003) analyzes how employees display affect in their service encounters and how those encounters are perceived. She surveys 131 university administrative assistants about their service encounters and the degree to which they employ “surface acting” (Grandey 2003, p. 86) in which they express positive emotions exclusively with their face or “deep acting” (Grandey 2003, p. 86) in which they genuinely feel positive. As a dramaturgical perspective on these types of acting would suggest (Grove and Fisk 1989), service encounters that involve surface acting are rated less positive than those using deep acting. Furthermore, only surface acting is associated with emotional exhaustion among employees.

Other studies set out to investigate how constituents perceive and construe theatrical, aesthetic experiences in and around corporations. For example, to this end, Biehl-Missal (2011) attends about 40 annual general meetings, press conferences, and analyst meetings of German companies listed on the stock exchange. Drawing on performance theory, she describes how companies strategically employed lighting and other dramaturgical techniques to either make audience members feel more like passive spectators (e.g., in press conferences or annual general meetings) or invoke a feeling of equality (e.g., during analyst meetings). Similarly, Boje et al. (2004) examine the scandalous bankruptcy of Houston-based energy company Enron. The authors use critical dramaturgy theory to guide their analysis of a large body of news articles, US Congress transcripts, and web reports about the scandal. They find that Enron used a wide array of narratives to deceive employees, auditors, and the public in general, which ultimately led to the “Greek mega-tragedy” (Boje et al. 2004, p. 757) that was Enron’s collapse. The authors suggest that transnational corporations, such as Enron, employ theatrical spectacles that “heroize global virtual corporations and free markets, while distancing (…) [themselves] from responsibility over their far-flung global energy-supply chains, where particularly exploitive conditions flourish” (Boje et al. 2004, p. 752). Organizations are even conceptualized as modern incarnations of spectacles that completely mask, replace, or perform their underlying realities (Flyverbom and Reinecke 2017).

4.3.2 Contributions to the conversation on “leadership”

The second sub-stream of literature in quadrant three contributes to research on leadership. These studies inject an interactive perspective derived from dramaturgical theories (Goffman 1959) into leadership research. According to this view, leaders, and followers construct leader authenticity, celebrity, and charisma in a reciprocal process (Gardner and Avolio 1998; Jackson 1996; Ladkin and Taylor 2010). Specifically, Gardner and Avolio (1998) propose a four-phase model through which the leader secures their image as a charismatic leader. First, by framing their vision, leaders enable “people to see the world that (…) [they] see” (Fairhurst and Sarr 1996, p. 50). Second, leaders extend their framing into scripts to coordinate and integrate actors’ behaviors. Third, leaders stage their appearance by selecting and manipulating symbols. Fourth, leaders perform their script by using “exemplification,” “promotion,” and “facework” (Gardner and Avolio 1998, p. 44–47) as impression-management strategies.

Weischer et al. (2013) analyze the concept of authentic leadership (Avolio and Gardner 2005). The authors conduct two online experiments in order to assess the influence of “enactment,” i.e., the physical and nonverbal parts of leaders’ communication (Stanislavski 1996), and “life storytelling,” i.e., narratives about the leader’s personal history (Luthans and Avolio 2003) on perceived leader authenticity. Under different experimental conditions, participants watch CEO speeches given by professional actors in which enactment and life storytelling are manipulated. In line with theories on organizational dramaturgy (Gardner 1992) and theoretical pieces on “embodied authentic leadership” (Ladkin and Taylor 2010, p. 65), the authors find that enactment predicts perceived leader authenticity, while storytelling partially predicts perceived leader authenticity. Furthermore, high perceived leader authenticity gives rise to high levels of trust and positive emotions among followers (Weischer et al. 2013).

Scholars in this sub-stream also scrutinize how leaders can project distorted images of themselves and their organizations by employing dramaturgical techniques (Jackson 1996; Kendall 1993; Sinha et al. 2012). Sinha et al. (2012), for example, study how celebrity CEOs’ characteristics and actions affect organizational outcomes. By applying a dramaturgical perspective (Goffman 1959) to the case of the failed acquisition of the airline Ansett Australia by Air New Zealand in 2001, the authors find that the newly appointed celebrity CEO Gary Toomey, the media, and other stakeholders co-created a drama through a series of performances. Specifically, the CEO and his co-participants preserved the illusion of control over the events, ultimately resulting in Toomey’s over-commitment to a failing strategy. Finally, the authors suggest that organizational performance is highly influenced by their celebrity CEOs’ sense-making processes (Sinha et al. 2012).

4.4 Quadrant 4: understanding organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts practices

You can’t improvise on nothin’, man. You gotta improvise on somethin’.

(Bassist-composer Charles Mingus, as cited by Kernfeld 1995, p. 120)

The 13 studies (15% of the sample) categorized in this quadrant employ performing-arts practices to guide their analysis of organizational phenomena. Weick (1992), for example, views jazz ensembles, orchestras, and drama groups as prototypical organizations that offer rich grounds for transferring principles of improvising, performing, acting, and persuading to the organizational context. One of the most important issues in this regard is how to achieve and foster creativity and innovation in organizations.

Similarly to practitioner-oriented literature that views creativity as consisting of specific vocabulary and grammar, the authors of the studies in this quadrant suggest that creativity can be replicated, taught, and practiced (Kao 1996). Practitioners like Vaill even recommend that managers “practice, practice, practice” (1989, p. 109) in order to successfully apply performing-arts practices in organizational contexts and create a basis from which creativity can blossom. In this vein, studies predominantly contribute to the conversations on mental models and representations (e.g., Berniker 1998; Ortmann and Sydow 2018; Weick 1998; Zack 2000), and organizational learning and memory (e.g., Barrett and Peplowski 1998; Kamoche and Pina e Cunha 2001), both of which the AOM’s MOC division lists as major topics of interest.

4.4.1 Contributions to the conversation on “mental models and representations”

Studies contributing to the conversation on mental models and representations focus on jazz music and theater as suitable sources for mental models that can be transferred from the context of the performing arts to the organizational context. Weick’s (1998) essay on “Improvisation as a mindset for organizational analysis” introduced the jazz metaphor to organizations by transferring the mental model and practice of improvising to organizational theory. Specifically, Weick (1998) proposes that the mindset of jazz improvisation can inform organizational theory, especially the framing and understanding of organizational improvisation. The author defines improvisation as “composing on the spur of the moment” (Weick, 1998, p. 548), which he conceptualizes as the end of a continuum that starts with interpreting, embellishing, or varying a melody. In other words, “improvisation is guided activity whose guidance comes from elapsed patterns discovered retrospectively” (Weick, 1998, p. 547). Weick (1998) also claims that the jazz improvisation metaphor can help conceptualize organizational improvisation as “mixing the intended and the emergent” (p. 551)—as order borne out of variation and retention, which can adapt spontaneously but is also often ignored in favor of routines.

Relatedly, Ortmann and Sydow (2018) explore Nietzsche’s invocation of the creative potential of constraints, and examine how the concept of “dancing in chains” (Nietzsche 1986, p. 343) can serve as a mindset for creativity-enhancing practices in organizations. While constraints, such as formal rules or scarce resources, have long been conceptualized as exclusively inhibiting creativity (e.g., Shalley et al. 2004), contemporary organizational theory has begun to embrace the idea that they might also enable creativity (Lampel et al. 2014). The authors argue that Nietzsche’s metaphor adds three layers to the idea of creativity-provoking constraints. First, organizational inertia is conceptualized as “old chains,” which restrict and enable creativity by reducing feasible alternatives. Second, within these chains, organizations and individual actors can “dance.” In other words, they can create freely—even more so than without any constraints, as there is no creatio ex nihilo, or “pure primary production” (Ortmann and Sydow 2018, p. 904). Third, “dancing in old chains” can have unintended effects and create “new chains,” or constraints. These new constraints might even restrict future organizational actions, similar to the path dependence experienced by the devil Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust I.Footnote 10

4.4.2 Contributions to the conversation on “organizational learning and memory”

Another sub-stream focuses on how specific performance practices can inform organizational learning and memory. In particular, studies pertaining to this category identify best practices in improvisational techniques stemming from jazz music and improvisational theater and investigate how they can be aimed at organization members’ learning, repeating, and imitating of specific rules so that organization members can build a repertoire of skills to build new patterns (Barrett 1998; Weick 1992). In many ways, this literature follows Louis Armstrong's preconception that creativity requires an internalized and readily available set of skills: “If you have to ask what jazz is, you’ll never know” (Bartlett 1968, p. 1046).

Perhaps most comprehensively, Barrett (1998) proposes seven characteristics of jazz improvisation that can be readily applied to organizational practices of improvisation. First, organizational actors can deliberately interrupt habits to provoke new responses, just like veteran jazz musicians often call tunes in a key that the band has not rehearsed. This technique is similar to “nonsense naming” in improvisational theater, where individuals quickly and deliberately assign incorrect names to everyday objects in order to break habitual perceptions (Crossan 1998). Second, organizations and their actors can create an “aesthetic of imperfection” (Barrett 1998, p. 611), just like jazz improvisers frequently make errors sound intentional, adjust their playing accordingly, and continue (Barrett 1998). Similarly, actors often practice “switch,” where an outside actor can freeze a play and rearrange the scene, and then the actors have to continue with the new scene (Crossan 1998). Third, organizations can make use of “minimal structures” (Kamoche and Pina e Cunha 2001, p. 733), such as rapid prototyping, which provides actors with maximum flexibility and a minimum of commonality (Ortmann and Sydow 2018; Pasmore 1998). Its equivalent in jazz music is the guiding structure of agreed-upon phrases and chords on which musicians improvise (Barrett 1998). Fourth, organizational members can strive for an intuitive synchronization in order to achieve flow (Csikszentmihalyi 1990), just as jazz musicians who have established “a groove” (Barrett 1998, p. 613) often feel like they “followed the music (…) wherever it wanted to go.” (Bassist Buster Williams in Berliner 1994, p. 392). Fifth, actors can practice bricolage (e.g., Baker and Nelson 2005). In other words, they can manage with “whatever is at hand” (Lévi-Strauss 1967), re-directing their actions in any moment based on their prior actions (Ortmann and Sydow 2018), just as jazz improvisers make sense of their playing in retrospect but cannot predict what is going to happen next (Gioia 1988). Sixth, new organizational members can learn the language of their organization from seasoned practitioners, just like jazz musicians get together in informal jam sessions, and pass on their standard keys and tempos to novices (Barrett 1998). Seventh, organizations can provide structures that allow actors to alternate between leading and supporting their colleagues. This practice is called “soloing”—i.e., playing the lead melody—and “comping”—i.e., accompanying the soloist (Barrett 1998). Comparably, theater actors practice taking turns by narrating one-word stories in which every participant adds one word to collectively build a story (Crossan 1998).

5 Opportunities for future research

As outlined above, interest in the performing arts as an empirical and theoretical research context is surging (Giorcelli and Moser 2020; Han and Ravid 2020; Janssens and Steyaert 2020; Rouse and Harrison 2022; Siganos and Tabner 2020). The studies in our sample hint at two reasons for this surge. First, the traditional, Taylorist (Merrill 1960) view of the organization as a “machine” (Clancy 1999, p. 15) operating in a stable environment (Perrow 1970) seems no longer adequate. Today’s volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous environments (Bechky and Okhuysen 2011; Brown and Eisenhardt 1997) undermine the very foundations of established organizations (König et al. 2016). As such, alternative, less mechanistic views of organizations and organizing—which characterize much, albeit not all, of the performing arts—might be more adequate lenses for contemporary organization theory. Second, how organizations appear “on stage,” both metaphorically (Cornelissen 2004; Hatch and Weick 1998) and literally (Gao et al. 2016; Love et al. 2017), has constantly become more important over time. As a consequence, it has also become more obvious to tap into the performing arts such as jazz (Berniker 1998; Weick 1998) as a source domain to conceptualize organizations. Our mapping of performing-arts-related organizational research uncovers several topics and research gaps that deserve the attention of organization scholars.

To help fill these gaps, we provide a structured research agenda, organizing future research opportunities according to our framework of organizational research in the context of the performing arts, as depicted in Table 4.

First, we encourage scholars to build on and extend the studies belonging to quadrant one (“advancing organizational theory by studying organizational phenomena in performing-arts contexts”). These studies harness the empirical context of the performing arts as an ‘extreme case’ for many issues at the heart of organizational research (Yin 1994). Indeed, careers in theater or music, for example, are generally characterized by more extreme individual dedication than careers in other professional fields, and the intrinsic and extrinsic sides of these careers often clash (Eikhof and Haunschild 2007; Riza and Heller 2015). Professional musicians’ training usually starts in childhood, making them interesting informants, especially for qualitative research on work motivation (Pratt 2009; Toraldo et al. 2019) and calling (Bunderson and Thompson 2009). The same applies to the “embodied leadership practice” (Ladkin 2008, p. 31) of musicians and conductors, which is highly suitable for uncovering how leaders use micro-level, implicit leadership practices (Ladkin 2008; Ladkin and Taylor 2010).

Specifically, we envision scholars to leverage performing-arts organizations and their inherent stability, making it possible to isolate focal organizational mechanisms from confounding variables (Durand and Kremp 2016). We recommend, for example, more research on symphony orchestras, which have maintained their core structure and functions since at least the mid-nineteenth century (Raynor 1978). As Allmendinger and Hackman noted, data from symphony orchestras are especially valuable because of these organizations’ well-defined core task, which is often similar within and across nations: “symphony orchestras around the world play largely the same repertoire with roughly the same number and mix of players” (1996, p. 340). At the same time, we see promising avenues for research on changes in deeply institutionalized practices in and around the performing arts. For example, the emergence of historically-informed music performance (Butt 2002) might allow scholars to gain a deeper understanding of phenomena such as institutional work, institutional entrepreneurship, and discontinuous, non-paradigmatic change (König et al. 2012; Lawrence et al. 2013; Weber et al. 2019).

In a similar vein, we envision scholars to engage in immersive research (e.g., Bougon et al. 1977). For instance, scholars can participate in theater productions as participant-observers or actors (Clark and Mangham 2004b) to better understand the principles and practices of collaborative leadership (Kramer and Crespy 2011), and how self-organizing groups work together (Goodman and Goodman 1976; Harrison and Rouse 2014). Particularly, we encourage scholars to conduct embedded, participant-observer research in dance companies and music ensembles to observe and ‘intuitively’ understand organizational change (Tsoukas and Chia 2002).

We further suggest that scholars use the abundant user-generated content on channels like YouTube, Instagram, Pinterest, or TikTok, which are platforms for musical, theatrical, and dance performances with millions of users. Given music and theater scholars’ increasing attention to the impact of digitalization on the creation, dissemination, and reception of cultural products (Théberge 2015), the lack of organizational research on digitally conveyed performing arts is surprising. Readily available digital data creates an interesting opportunity to analyze performing-arts productions. For instance, the Bolshoi theater and the Metropolitan Opera stream operas and ballet performances for free on YouTube and to more than 1000 theaters worldwide (Bolshoi Theatre 2020; The Metropolitan Opera 2020). Notably, audio and visual recordings of performances, such as those stored in the British National Archives and other databases, lend to multimodal analyses, which could also provide the ground for applying deep-learning algorithms to support theory development and testing.

Second, concerning quadrant two (“advancing organizational theory by studying performing-arts phenomena in organizational contexts”), our review highlights a lack of consensus regarding whether and to what extent organizational theater can or should instill lasting organizational change (Clark and Mangham 2004b; Meisiek and Barry 2007). Apparently, organizations have to carefully design and discuss the implementation of theater-based interventions (Clark and Mangham 2004a; Czarniawska-Joerges and Wolff 1991; Meisiek 2004) and consider potential unintended and uncontrollable side effects (Nissley et al. 2004). In this spirit, we call for further examinations of the impact of organizational theater on organizational learning and change. To this end, authors might use the many possibilities for participant observation (Clark and Mangham 2004a) and personally witness how organizational theater is produced, implemented, and evaluated (Clark and Mangham 2004b).

Third, as to quadrant three (“understanding organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts theories”), studies mainly propose dramaturgical lenses—drawing on dramatism (Burke 1968) and dramaturgy (Goffman 1959)—to advance our understanding of organizational phenomena. For example, dramaturgical efforts allow scholars to uncover the mechanisms of organizations’ impression management in ‘good’ (Biehl-Missal 2011) and ‘bad’ times (Boje et al. 2004); to gauge employees’ performance (Grandey 2003); and to analyze why leaders are perceived as charismatic and authentic (Gardner and Avolio 1998; Weischer et al. 2013; Westley and Mintzberg 1989).

We further suggest researchers apply dance-related theories (e.g., Ortmann and Sydow 2018) and music-related theories (Plack 2014). For instance, future studies could investigate dance-related concepts such as “lead and follow,” which is the basis for most social or partner dances (DeMers 2013). In this concept, the leader is responsible for guiding the follower, smoothly initiating movement, guiding the duo towards transition, and ultimately coordinating teamwork. In some social dances, such as the Argentinian tango, the roles of leader and follower can even change during one dance. Some scholars have begun to transfer the lead-and-follow concept to organizational change processes, such as the idea that conflict can be overcome by the willingness of all participants to listen to and “get changed by the other” (Wetzel and Nees 2017, p. 58). As for music-related theories, scholars could apply concepts such as counterpoint or polyphony, for example, to the analysis of executive communication (de Oliveira Kuhn et al. 2019).

Fourth, while some researchers in quadrant four (“understanding organizational phenomena through the prism of performing-arts practices”) stress the potential of metaphors to yield non-trivial insights into organizational structures (Hatch 1998), others highlight their limitations and advocate for their critical use (Cornelissen 2004, 2005; Hatch and Weick 1998). This literature extends the tradition of using metaphors to describe organizational reality, such as metaphors of chaos (e.g., Thiétart and Forgues 1995), identity (Cornelissen 2002; Gioia et al. 2000), mind (e.g., Weick and Roberts 1993), and memory (e.g., Walsh and Ungson 1991). In particular, it conceptualizes jazz combos or theater companies as prototypical organizations (Barrett 1998; Meisiek and Barry 2007; Schreyögg and Häpfl 2004), with managers being the jazz combo and employees dancing to the managers’ tune (e.g., Berniker 1998). However, Weick (1998) points out that most organizations seek to produce standardized outputs while the performing arts generally pursue the creation of something new and previously unheard. In a similar vein, Cornelissen (2004) highlights that the ‘organization as theater’ metaphor has not advanced organization theory, but has merely labeled organizational concepts differently—organizational members are simply called ‘actors’ or ‘characters’ who play different ‘roles’ and interpret their ‘scripts.’