Abstract

This paper considers a two player game between a base runner and a pitcher in Major League Baseball. To make testable predictions, we exploit the fact that generally left-handed pitchers are more proficient at pick-off throws to first base than their right-handed counterparts. We find evidence in support of mixed strategy play.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Camerer (2003) chapter 3 for a review of the literature.

Sports data have been widely used in economic research. Because the sports industry is so large, researchers have analyzed it in its own right. See Cebula et al. (2009) and (2013) for examples. Other researchers have used sports as a natural laboratory and they have generalized the results outside of sports. See Goff et al. (1997) for an illustrative example.

They also find that players and coaches are aware that it is an advantage to go first in a shootout and consequently would rather go first if they win the coin toss to determine shooting order.

Kocher et al. (2012) enlarged the sample and failed to find a first mover advantage in penalty kicks.

The work most closely related to our own is an unpublished study by Turocy (2004), who used the stolen base in baseball to represent an inspection game. He shows that the offensive performance increases when a better runner is on first base. The idea is that when the pitcher focuses more effort on a runner, he can put less effort into pitching to a batter, which results in better offensive performance.

See the data appendix for precise definitions of the data.

We also added dummy variables for outs, but these were not significant and were thus eliminated.

In this estimate, the estimated coefficient and especially the estimated standard error were very high for the extra inning dummy variable. This dummy variable was equal to one for only eight observations. We also ran the regression leaving out the extra inning dummy. The results remained similar to those reported in column 3. The variable of primary interest, Lefty, had a coefficient of −0.302 and a t-statistic of −2.99 in this specification.

Gonzalez-Diaz et al. (2010) assume that better performance in one circumstance lessens one’s opportunity to perform well in another circumstance. They find that for a given level of ability, a tennis player’s ability to choose when to perform well contributes to the player’s success. The player that can perform well at critical moments has an advantage.

We also considered another tactic that pitchers can use to deter a base runner. Pitchouts are when the pitcher purposely throws high and outside to the catcher (always a ball) so that the catcher is eminently ready to try and throw out a runner trying to steal second. There were only eight pitchouts in our sample; when added in to the model, it made the Lefty variable slightly larger, reinforcing the notion that lefties better deter potential base stealers.

Most of the baseball information (data) used in this paper was obtained free of charge from and is copyrighted by Retrosheet. Interested parties may contact Retrosheet at “www.retrosheet.org/”.

We follow Turocy (2004)’s strategy of limiting the sample to situations with a man on first base and no one out.

Turocy (2005) found that given the rate of success teams have when they attempt to steal second base, the expected payoff from stealing second base was nearly equal to the expected cost of getting caught stealing. His dependent variable was runs scored by a team in a season.

The 413 runs represents 4 % of the total runs scored in the AL during the 2010 season.

Total runs for the season were found on MLB Team Batting Stats on ESPN’s web site.

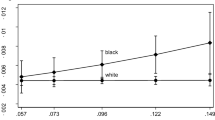

When the control variables are at their mean levels, a base runner will run 7.178 % of the time against right-handed pitchers and 2.520 % of the time against left-handed pitchers.

In future research, we will test the mixed strategy prediction that pick-off throws are serially independent.

References

Apesteguia, J., & Palacios-Huerta, I. (2010). Psychological pressure in competitive environments: Evidence from a Randomized natural experiment. American Economic Review, 100(5), 2548–2564.

Camerer, C. F. (2003). Behavioral Game theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cebula, R. J., Toma, M., & Carmichael, J. (2009). Attendance and promotions in minor league baseball: the Carolina league. Applied Economics, 41(25), 3209–3214.

Cebula, R. J., Coombs, C. K., Lawson, L., & Foley, M. (2013). The impacts of promotions / marketing, scheduling, and economic factors on total gross revenues for minor league baseball teams. International Advances in Economic Research, 19(3), 249–257.

Chiappori, P. A., Levitt, S., & Groseclose, T. (2002). Testing mixed strategy equilibria when players are heterogeneous: the case of penalty kicks in soccer. American Economic Review, 92(4), 1138–1151.

Goff, B., Shughart, W., & Tollison, R. D. (1997). Batter up! Moral hazard and the effects of the designated hitter rule on hit batsmen. Economic Inquiry, 35, 555–561.

Gonzalez-Diaz, J., Gossner, O. & Rogers, B. (2010). Performing best when it matters most: evidence from professional tennis. Working paper, December 11, 2010.

Halket, J. (2009). Finding wins. Hardball Times, available at http://www.hardballtimes.com/finding-wins/. Accessed August, 2014.

Hsu, S.-H., Huang, C.-Y., & Tang, C.-T. (2007). Minimax play at Wimbledon: Comment. The American Economic Review, 97, 517–523.

Kocher, M. G., Lenz, M., & Sutter, M. (2012). Psychological pressure in competitive environments: New evidence from randomized natural experiments. Management Science, 58(8), 1585–1591.

McGarrity, J. (2012). The economics of crime reconsidered: A game theoretic approach with an empirical test from major league baseball. In S. Shmanske & L. Kahane (Eds), The Oxford handbook of sports economics, (Volume 2).Oxford University Press.

McGarrity, J. P., & Linnen, B. (2010). Pass or run: An empirical test of the matching pennies game using data from the National Football League. Southern Economic Journal, 76(3), 791–810.

Palacios-Huerta, I. (2003). Professionals play Minimax. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 395–415.

Pankin, M. (2009). What do rock/paper/scissors and baseball have in common? Presentation at SABR 39, 7/31/2009, Washington, D.C.

Paserman, M. D. (2010). Gender differences in performance in competitive environments? Evidence from professional tennis players. Working paper, January.

Turocy, T. L. (2004). A theory of theft: an inspection game model of the stolen base play in baseball. Working paper.

Turocy, T. L. (2005). Offensive performance, omitted variables, and the value of speed in baseball. Economic Letters, 89, 283–286.

Walker, M., & Wooders, J. (2001). Minimax play at Wimbledon. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1521–1538.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for helpful comments: Noel Campbell, Mike Casey, Ling He, Ed Lopez, Evan Osborne, Marc Poitras, Bill Shughart, Dan Sutter, and Robert Tollison.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Data Definitions

Appendix: Data Definitions

Dataset one: all pitches or throws to first during every game in every AL park between June 9 and June 13, 2010 with a runner on first base only. In such circumstances, a pitcher either makes a pitch to the batter or throws to first to try and get the runner out. (n = 2046). Unit of analysis is a pitch to the batter or a throw to first base by the pitcher.

-

1)

Throw to first is a dummy variable equal to one if the pitcher throws to first base and equal to zero if the pitcher throws to home plate.

-

2)

Lefty is a dummy variable equal to one if the pitcher is left-handed.

-

3)

OPS (On base Plus Slugging) is a measure of the player’s ability to hit the ball and to get on base. It is calculated by adding the player’s career on base percentage plus slugging percentage. On base percentage is calculated by adding hits (H), walks (BB or base on balls), and hit by pitches (HBP) divided by at-bats (AB) plus walks (BB) plus sacrifice flies (SF) plus hit by pitches. Slugging percentage is calculated by adding total bases (number of singles, doubles, triples, and home runs) divided by at-bats. As an example, Babe Ruth has the highest career OPS in major league history at 1.16.

$$ On\kern0.2em base\kern0.2em percentage=\left(H+BB+HBP\right)\kern0.2em /\left( AB+BB+SF+HBP\right) $$$$ \mathrm{Slugging}\kern0.2em \mathrm{percentage}=\left( singles+\left(2\ *\kern0.2em doubles\right)+\left(3\ *\kern0.2em triples\right)+\left(4\ *\kern0.2em \mathrm{home}\ \mathrm{runs}\right)\right)/\mathrm{at}\ \mathrm{bats} $$ -

4)

Runner Quality is a measure of a player’s ability to steal a base taking into account how many times he made it to first base. The more times on first, the more opportunity a runner has to steal. This is a career statistic, found by dividing career stolen bases by number of career singles, walks (BB), and hit by pitches (HBP) (these are the ways to reach first base).

$$ Runner\kern0.2em quality= career\kern0.2em stolen\kern0.2em bases\ /\left( singles+BB+HBP\right) $$ -

5)

Score Difference is the difference in runs scored at the time of the pitch or throw to first. It is the absolute value of the home team score – visitor team score.

-

6)

Catcher Quality is a measure of the catcher’s ability to throw out a base stealer. It is measured by dividing the number of times he threw a base stealer out by the number of times a runner tried to steal a base, throughout his career (through the end of the 2009 season).

-

7)

Ball1 is a dummy variable equal to one if there is one ball in the count and 0 if not. Ball2 and Ball3 are dummy variables if there is the number of balls indicated in the variable name. A batter who reaches four balls “walks,” or is awarded first on a base on balls because the pitcher did not throw strikes.

-

8)

Strike1 is a dummy variable equal to one if there is one strike in the count. Strike2 is a dummy variable if there are two strikes in the count. A batter is called out if he gets three strikes.

-

9)

Line i is a vector of nine dummy variables that indicates the order the batter hits in the lineup. It ranges from one (the batter who hits first) to nine. In general, better hitters bat higher in the lineup.

-

10)

Inning i is a vector of 11 dummy variables that indicate the inning. It ranges from one to eleven. Games have nine innings, but if the score is tied after nine, there are “extra innings,” or additional innings until the game is no longer tied. In this data set, one dummy variable is used to indicate an extra inning game.

Dataset two: every at-bat where there is a runner on first base and no one out for every game during the 2010 season played at AL ball parks (n = 5748). Unit of analysis is an at-bat.

# runs: number of total runs scored in the inning in which the at-bat occurred. It is only the runs scored by the team batting.

Runner quality: same as dataset one.

Pitcher ERA: a measure of how good a pitcher is, based on the number of innings pitched (career) and the number of earned runs allowed (career). An “earned” run is charged to a pitcher when a batter he pitched to reaches first base without the aid of an error, and eventually scores a run, also without the aid of an error. Should an error (mishandling a ball or poor throw by a fielder, as determined by the “official scorer”) occur that leads to a runner scoring, the run is “unearned,” ERA is calculated by standardizing to 9, the number of innings a normal major league game lasts. It is calculated by the following:

Steal Attempt is a dummy variable that equals one if the offensive player on first base attempts to steal second base.

Left-Handed Pitcher is a dummy variable equal to one if the pitcher throws with his left hand.

Score Difference: same as dataset one.

OPS (inning) is the average OPS of the batters who hit in the remainder of the inning.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Downey, J., McGarrity, J.P. Pick off Throws, Stolen Bases, and Southpaws: A Comparative Static Analysis of a Mixed Strategy Game. Atl Econ J 43, 319–335 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-015-9464-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-015-9464-4