Abstract

Objectives

Eyewitness misidentifications have been implicated in many of the DNA exoneration cases that have come to light in recent years. One reform designed to address this problem involves switching from simultaneous lineups to sequential lineups, and our goal was to test the diagnostic accuracy of these two procedures using actual eyewitnesses.

Methods

In a recent randomized field trial comparing the performance of simultaneous and sequential lineups in the real world, suspect ID rates were found to be similar for the two procedures. Filler ID rates were found to be slightly (but, in the key test, nonsignificantly) higher for simultaneous than sequential lineups, but fillers will not be prosecuted even if identified. Moreover, filler IDs may not provide reliable information about innocent suspect IDs. Here, we use two different proxy measures for ground truth of guilt versus innocence for suspects identified from simultaneous or sequential lineups in that same field study.

Results

The results indicate that innocent suspects are, if anything, less likely to be mistakenly identified—and guilty suspects are more likely to be correctly identified—from simultaneous lineups compared to sequential lineups.

Conclusions

Filler identifications are not necessarily predictive of the more consequential error of misidentifying an innocent suspect. With regard to actual suspect identifications, simultaneous lineups are diagnostically superior to sequential lineups. These findings are consistent with recent laboratory-based studies using receiver operating characteristic analysis suggesting that simultaneous lineups make it easier for eyewitnesses to tell the difference between innocent and guilty suspects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In keeping with actual practices, witnesses in the AJS field study were permitted to view the photos in the sequential lineup a second time if they requested it. In laboratory studies, by contrast, only one lap is typically allowed. Wells et al. (2014) analyzed the data two ways: first, by using the lap 1 results only (because this allowed them to compare the results to those found in laboratory studies where second laps are typically not allowed, so the lap 1 choices represent the final choices by the witness/victims in those studies); and second, by analyzing the results that accurately reflected how the sequential procedure was used in the field trial (and how it is typically used in field administration of sequential procedures, i.e. allowing a second lap on request). In the first analysis, filler ID rates were significantly higher for simultaneous compared to sequential lineups (although this analysis did not include the final decisions of the cases in which a second lap was actually requested, n = 37), but in the second analysis reflecting how the sequential procedure was actually used in the field trial, the difference in filler ID rates (specifically, 29 filler IDs out of 236 sequential lineups vs. 46 filler IDs out of 258 simultaneous lineups) was not significant (p = .09, though reported as p = .08 by Wells et al.). Only the latter (non-significant) result—the one that included the lap 2 decisions of the 16 % of witnesses who requested a second viewing–is relevant to the performance of the sequential lineup in the real world. For this reason, our Phase 2 analysis included the final lap 2 decisions as well.

These values were taken from Table 3 of Steblay et al. (2011) because those data came from published studies that used adults as subjects and used a full simultaneous/sequential by perpetrator-present/perpetrator-absent design. For the false alarm rates, we used the values representing "identification of designated innocent suspect".

We make the assumption of equal base rates of target-present and target-absent lineups throughout (in which case the diagnosticity ratio = the posterior odds of guilt) for the sake of our illustrative examples, but none of our final conclusions depend on that assumption.

Theoretically, they could be endangered if district attorneys actually prosecuted known innocent fillers, but this has not to our knowledge ever been demonstrated.

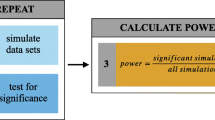

As suggested by our power analysis.

Each group was made up of one police investigator, one prosecutor, one defense attorney and one judge.

The higher average rating that was observed for suspect picks from simultaneous lineups should be balanced by a higher average rating for both filler picks and no picks from sequential lineups (because the guilty suspects who did not show up in sequential suspect picks should instead show up in the other two categories, increasing those ratings). However, that effect should be very small because there were many more filler picks and no picks in the original sample of 313 cases than suspect picks (thereby diluting the expected effect). Moreover, because only a random sample of these cases was selected for rating in Phase 2, the expected small difference in the average rating for filler picks and no picks from simultaneous and sequential lineups would have a wide confidence interval (one that would easily encompass the small and non-significant difference that was observed in favor of simultaneous lineups).

Double blind administration is when not only the witness but also the lineup administrator is unaware of who the suspect is (the administrator is not the case detective) thereby eliminating the possibility that even an inadvertent cue could be sent to the witness during the photo array procedure.

If the instructions were altered to say "too many guilty suspects are being released, so please make an ID even if you have only a slight hunch that you see the perpetrator in the lineup," then almost all witnesses would make an identification, whereas almost no one would make an ID if the instructions instead said "too many innocent suspects have been misidentified in recent years, so please don't make any ID unless you are 100 % certain of being correct and could not possibly be making an error".

References

Amendola, K.L., & Slipka, M.G. (2009). Strength of evidence scale. Unpublished instrument. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

Amendola, K.L., Valdovinos, M.D., Hamilton, E.E., Slipka, M.G., Sigler, M., and Kaufman, A. (2014). Photo arrays in eyewitness identification procedures: Presentation methods, influence of ID decisions on experts’ evaluations of evidentiary strength, and follow-up on the AJS Eyewitness ID Field Study. Washington, DC: Police Foundation. http://www.policefoundation.org/sites/g/files/g798246/f/201403/FINAL%20EWID%20REPORT--Police%20Foundation%281%29-1_0.pdf

Brewer, N., Weber, N., & Semmler, C. (2005). Eyewitness identification. In N. Brewer & K. D. Williams (Eds.), Psychology and law: An empirical perspective (pp. 177–221). New York: Guilford.

Carlson, C. A., & Carlson, M. A. (2014). An evaluation of perpetrator distinctiveness, weapon presence, and lineup presentation using ROC analysis. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 45–53.

Carlson, C. A., Gronlund, S. D., & Clark, S. E. (2008). Lineup composition, suspect position, and the sequential lineup advantage. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 14, 118–128.

Clark, S. E. (2005). A re-examination of the effects of biased lineup instructions in eyewitness identification. Law and Human Behavior, 29, 395–424.

Clark, S. E. (2012). Costs and benefits of eyewitness identification reform: Psychological science and public policy. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 238–259.

Dobolyi, D. G., & Dodson, C. S. (2013). Eyewitness confidence in simultaneous and sequential lineups: a criterion shift account for sequential mistaken identification overconfidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 19, 345–357.

Durose, M.R., & Langan, P.A. (2003). Felony Sentences in state courts, 2000. (Report No. NCJ 198821). Retrieved from Bureau of Justice Statistics website: http://bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fssc00.pdf

Gronlund, S. D., Carlson, C. A., Dailey, S. B., & Goodsell, C. A. (2009). Robustness of the sequential lineup advantage. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 15, 140–152.

Gronlund, S. D., Carlson, C. A., Neuschatz, J. S., Goodsell, C. A., Wetmore, S. A., Wooten, A., & Graham, M. (2012). Showups versus lineups: An evaluation using ROC analysis. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1, 221–228.

Gronlund, S. D., Wixted, J. T., & Mickes, L. (2014). Evaluating eyewitness identification procedures using ROC analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 3–10.

Horry, R., Halford, P., Brewer, N., Milne, R., & Bull, R. (2014). Archival analysis of eyewitness identification test outcomes: What can they tell us about eyewitness memory? Law and Human Behavior, 38, 94–108.

Lindsay, R. C. L., & Wells, G. L. (1985). Improving eyewitness identifications from lineups: Simultaneous versus sequential lineup presentation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70, 556–564.

McQuiston-Surrett, D. E., Malpass, R. S., & Tredoux, C. G. (2006). Sequential vs. Simultaneous lineups: a review of methods, data, and theory. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 12, 137–169.

Mickes, L., Flowe, H. D., & Wixted, J. T. (2012). Receiver operating characteristic analysis of eyewitness memory: Comparing the diagnostic accuracy of simultaneous and sequential lineups. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18, 361–376.

Palmer, M. A., Brewer, N., & Weber, N. (2012). The information gained from Witnesses' responses to an initial "blank" lineup. Law and Human Behavior, 36, 439–447.

Perfect, T. J., & Weber, N. (2012). How should witnesses regulate the accuracy of their identification decisions: One step forward, two steps back? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38, 1810–1818.

Police Executive Research Forum (2013). A National Survey of Eyewitness Identification Procedures in Law Enforcement Agencies. http://policeforum.org/library/eyewitness-identification/NIJEyewitnessReport.pdf

Steblay, N. M., & Phillips, J. D. (2011). The not-sure response option in sequential lineup practice. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25, 768–774.

Steblay, N. K., Dysart, J. E., & Wells, G. L. (2011). Seventy-two tests of the sequential lineup superiority effect: A meta-analysis and policy discussion. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 17, 99–139.

Weber, N., & Perfect, T. J. (2012). Improving eyewitness identification accuracy by screening out those who say they don’t know. Law and Human Behavior, 36, 28–36.

Wells, G. L. (1978). Applied eyewitness-testimony research: system variables and estimator variables. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 12, 1546–1557.

Wells, G. L. (1984). The psychology of lineup identifications. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 14, 89–103.

Wells, G.L., Steblay, N.K., & Dysart, J.E. (2011). A test of the simultaneous vs. sequential lineup methods: An initial report of the AJS national eyewitness identification field studies. Des Moines, Iowa: American Judicature Society. Retrieved from: http://www.popcenter.org/library/reading/PDFs/lineupmethods.pdf

Wells, G. L., Steblay, N. K., & Dysart, J. (2012). Eyewitness identification Reforms: Are suggestiveness-induced hits and guesses true hits? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 264–271.

Wells, G.L., Steblay, N.K., & Dysart, J.E. (2014). Double-Blind Photo-Lineups Using Actual Eyewitnesses: An Experimental Test of a Sequential versus Simultaneous Lineup Procedure. Law and Human Behavior

Wixted, J. T., & Mickes, L. (2012). The field of eyewitness memory should abandon "probative value" and embrace Receiver Operating Characteristic analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 275–278.

Wixted, J. T., & Mickes, L. (2014). A signal-detection-based diagnostic feature-detection model of eyewitness identification. Psychological Review, 121, 262–276.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amendola, K.L., Wixted, J.T. Comparing the diagnostic accuracy of suspect identifications made by actual eyewitnesses from simultaneous and sequential lineups in a randomized field trial. J Exp Criminol 11, 263–284 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-014-9219-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-014-9219-2