Abstract

Over the last four decades, the majority of European farmland birds have shown marked population declines attributed to the intensification of agriculture. The Common Quail is a widespread farmland breeder across most of Europe. Its populations have shown marked decline, particularly pronounced at the end of the previous century. Ongoing agriculture intensification may be the factor responsible for the observed declines; however, links between species occurrence and farming intensification have not been addressed so far. We analyzed factors affecting the occurrence of the Quail in Poland using data from 722 1 × 1-km study plots and a set of 22 environmental variables, including proxies for agriculture intensification. Predictors were aggregated using PCAs and related to species presence/absence data using GAMs. The best-supported model of the species’ occurrence included eight variables and was clearly better (AIC weight = 0.54) than other models. Quails preferred open fields, showing high photosynthetic activity in March or June, with rather low precipitation and often at relatively high altitudes (up to 900 m a.s.l.). Importantly, quails were more frequent on plots located in regions with rather high inorganic fertilizer input, and showed no avoidance of areas with a high level of agriculture mechanization. We postulate that singing male quails are attracted to areas with medium or high intensity of agriculture but it may represent a maladaptive habitat choice enhanced by changing agriculture practices and peculiarities of the quail’s breeding strategy. Given the results, the quail cannot be classified as a good indicator of extensive traditional agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The decline of farmland birds observed over the past four decades across Europe is probably one of the most widely documented and publicized patterns of concerted population changes in conservation biology (Krebs et al. 1999; Donald et al. 2001; Benton 2007). Linked with intensification of agricultural practices, it spawned a large body of research on possible drivers of the observed changes (Chamberlain and Fuller 2000; Donald et al. 2001; Benton et al. 2002; Gregory et al. 2004; Newton 2004; Donald et al. 2006; Wretenberg et al. 2007; Butler et al. 2010). As a side issue, it also promoted further research on indices used to quantify and aggregate information on changes in abundance of multiple species (Gregory et al. 2005; van Strien et al. 2012).

However, not all farmland bird species are equally vulnerable to changing farming practices and the observed patterns of population changes do differ between countries, hampering our understanding of the exact mechanisms driving the observed changes (Fox 2005; Wretenberg et al. 2006; Reif et al. 2008; Tryjanowski et al. 2011). The Common Quail Coturnix coturnix is a widespread breeder across most of European farmland, but it is also one of the most enigmatic species of this habitat. It is the only species of Phasianidae that undertakes long-distance migrations, spending the winter in the Sahel zone. Migratory habits and Sahel wintering grounds are factors making the species more vulnerable than others to population declines (Sanderson et al. 2009). A large decline of the European Quail’s population was observed in 1970–1990, followed by a shallow decline hence after, coupled with some increase noted in northern parts of its range (BirdLife International 2004; Sanderson et al. 2009). Consequently, the continental population is classified as “depleted” and the quail is categorized among species with unfavorable conservation status in Europe (Species of European Conservation Concern, SPECs) in category 3 (BirdLife International 2004). The quail is known to be excessively harvested (mostly hunted) during autumn migration, particularly in the Mediterranean basin (Gallego et al. 1997; Puigcerver et al. 1998; Sardà-Palomera et al. 2012), which is a cause of concern, addressed recently by the EU management plan (EC 2009).

The Quail is highly mobile within a single breeding season, with individual birds dispersing between distant breeding sites. Probably, most European breeders first reproduce in northern Africa and the Mediterranean basin (south of 40°N) in March–April, and only then migrate to central and northern Europe to breed there for the second time in late May–July (Guyomarc’h et al. 1998; EC 2009). Quails arriving to central and northern Europe in late spring also include reproductively active birds hatched from first broods a couple of weeks earlier (Guyomarc’h et al. 1998; EC 2009). No doubt, male quails found on central European breeding grounds are highly nomadic, with a majority of radio-tracked birds staying no longer than 2 weeks in a single place (Herrmann and Dassow 2006).

Habitat preferences of the quail are rather poorly identified. A wide variety of crops are reported as preferred by the species (George 1996; Guyomarc’h et al. 1998; EC 2009; Sardà-Palomera et al. 2012), with no clear pattern emerging and inconsistent results regarding different countries and spring vs. autumn-sown crops. Probably, certain features of the sward structure (height, density of stems) may be more important than plant species or their variety. A radio-tracking study conducted in the farmland of East Germany was probably the most revealing one, showing that the quail preferred areas covered with dense to rather sparse, medium-height vegetation on sandy soils, with many weeds, often set-asides and spring-sown cereals, legumes, flax, and lupin (Herrmann and Dassow 2006).

The reported preferences for fallow land as breeding sites and for spring-sown cereals as singing places (Herrmann and Dassow 2006) do imply, however, that agricultural intensification is a possible threat, as the share of fallows and spring-sown cereals decreases with the increasing industrialization of farming practices in temperate Europe (Chamberlain and Fuller 2000; Wilson et al. 2009). Widespread use of pesticides in modern agriculture decreases the species’ preferred food supply during the breeding season, lending further support to the idea that modern farming is rather incompatible with habitat requirements of the quail (EC 2009). Agriculture intensification and associated habitat loss were identified as being of main importance for the species’ fortunes in the EU (EC 2009).

Recent papers describing the habitat preferences of quails (Sardà-Palomera and Vieites 2011; Sardà-Palomera et al. 2012) did not address the issue, as they did not examine variables related directly to the intensity of agriculture among all other predictors. We decided to extend the approach and analyze factors shaping the quail’s occurrence, using not only climatic variables but also an extensive set of covariates describing land use and indices of agricultural intensification. In this way, we wished to examine more directly the relationship between the quail’s occurrence and the intensity of farming in agricultural landscape. We used data from Poland, which is particularly suitable for this kind of analyses, given a large area of farmland (>180,000 km2) and the existing gradient of agriculture intensity across the country. Besides, we capitalize on the existing data from a countrywide survey of common breeding birds, yielding presence/absence data for >700 study plots representative for the country (Kuczyński and Chylarecki 2012). Presence/absence data recorded during planned surveys are clearly preferable to presence-only data in habitat modeling studies due to a multitude of reasons (Franklin 2009; Royle et al. 2012). Having access to good quality data on bird occurrences, coupled with existing environmental data from other sources, we aimed to: (1) identify variables linked to the occurrence of the quail in central European farmland, and (2) examine whether variables commonly used as proxies for agriculture intensification were important predictors of the quail’s occurrence.

Materials and methods

Bird data

The data come from the Common Breeding Bird Survey scheme (Chylarecki and Jawińska 2007; Kuczyński and Chylarecki 2012) and were collected in Poland in the years 2000–2009 in 722 grid cells of 1 km2 (Fig. 1). Squares treated as survey plots had been chosen at random out of 311,664 squares covering all of Poland. In particular breeding seasons, each plot was surveyed twice. The first visit took place between April 10 and May 15 and the second between May 16 and June 30. Within each survey plot, birds were counted while walking two parallel 1-km-long transects spaced approximately 500 m apart. Each survey started between the dawn and 9:00 am and took about 90 min. Each transect was divided into five 200-m sections, with birds recorded in three distance categories (<25, 25–100, >100 m) from the transect. During the 10-year period, each square was inspected on average in 5.0 (SD = 2.8) breeding seasons. Observers noted all birds seen or heard in the field, which—in the case of the quail—translated effectively into recording calling males, as visual contact with non-vocalizing individuals of this species was extremely scarce during the survey.

Environmental data

All remote sensing data were converted into GRASS GIS file format (Neteler and Mitasova 2008) and re-projected to coordinate system EPSG4284 projection (http://spatialreference.org/ref/epsg/4284/). All grid cells were characterized by geographical localization, altitude, climate conditions, relative proportion of individual habitat types, monthly rate of the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) from March to June, relative proportion of individual habitat types, and level of farming mechanization and inorganic fertilizer input.

Altitude (a.s.l.) and the difference between the highest and the lowest location (DENIW) came from digital evaluation model (DEM) dataset (GTOPO30), originally provided by the U.S. Geological Survey’s EROS Data Center (Sioux Falls, South Dakota).

Climate data were derived from the WorldClim database (http://www.worldclim.org), which is a set of global climate layers (climate grids) with spatial resolution of a square kilometer. All grid cells were featured by six variables, such as annual mean temperature (AMT), mean temperature of warmest quarter (MTWAQ), mean temperature of coldest quarter (MTCQ), annual precipitation (AP), precipitation of warmest quarter (PWAQ), and precipitation of coldest quarter (PCQ).

The original 37 land cover types are recognized in the CORINE Land Cover database (based on remote sensing with basic spatial units of 100 × 100 m), created in 2000, 2003, and 2006 from Landsat TM. On average, ten types of habitats were distinguished in each grid cell. The most frequent were environments classified as non-irrigated arable land, then coniferous forest, meadows, mixed forest, complex cultivation patterns, agricultural areas with natural vegetation, deciduous forest, shrub, water bodies, and inland marshes.

For each grid cell, we obtained monthly averages of the normalized differences vegetation indices (NDVI). The data were derived from the SPOT dataset (http://free.vgt.vito.be/) and were collected in the years 2000–2009. NDVI is an index of the green vegetation level, expressed as the mean monthly value (from March to June), calculated from three measurements taken every 10 days.

Data on farming mechanization and inorganic fertilizer input were obtained from Agricultural Census 2002 (http://www.stat.gov.pl/bdl/app/strona.html?p_name=indeks). The variables include the number of tractors (TRAC), cereal combine harvesters (HARV) per farm and tons of lime (FLIME), phosphatic (FPHOS), potassium (FPOTA), and nitrogenous fertilizers (FNITR) per hectare of an open habitat. However, the spatial resolution of these data is inconsistent with other class data because the data were collected for administrative units. Therefore, in each of the 16 administrative units of Poland, mechanization and inorganic fertilizers’ variables are expressed as the number of agricultural equipment pieces per hectare of an open habitat in each grid cell (1 km2) (i.e., the sum of such areas as non-irrigated arable fields, meadows, complex cultivation patterns, agricultural areas with natural vegetation), and analogically tons of fertilizers per the sum of non-irrigated arable fields area and complex cultivation patterns in each grid cell.

As the level of human population density we used images of lights at night (HUMAN). These datasets come from remote sensing data of 1-km resolution. The lights on the night map include lights from cities, towns, and other sites with persistent lighting. This kind of data is highly correlated with industrial activities (Small et al. 2005; Doll et al. 2007).

Data processing and analysis

We developed a predictive model of the Common Quail’s occurrence by comparing environmental conditions in grid cells where birds occurred with grid cells where they did not. A grid cell where a quail occurs is the one where at least one individual was recorded in three subsequent years of the research.

In order to avoid multicollinearity among environmental variables, the principal components analysis (PCA) was performed with the Varimax normalized rotation, separately for each of four environmental datasets (Quinn and Keough 2002). Principal components’ axes with eigenvalues >1 were retained as predictor variables in the analyses. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical package R (R Development Core Team 2010).

PCA of climate variables produced two axes, which explained 83.7 % of the original variation in climate variables (Table 1A). The first axis (PREC) had the highest loadings with precipitation variables, while the second (TEMP) with temperature variables. The use of inorganic fertilizers produced only one axis with eigenvalue >1, which explained 41 % of the variation (Table 1B).

Habitat variables derived from Corine Land Cover (CLC) linked with HUMAN produced seven components and explained 92.1 % of the variation (Table 1C). Finally, agricultural equipment use, reflecting the level of mechanization, produced one axis and explained 89.2 % of the variation (Table 1D). The Pearson correlation coefficients and variation inflation factor (VIF, using HH library in R; Heiberger 2013) were used to assess the relationship between all predictors (Table 2). VIF of 5 and above indicated a multicollinearity problem (O’Brien 2007). In the present study, VIF ranged from 1.09 to 13.69, therefore predictors whose VIF ≥ 5 were excluded from the analysis (Table 2).

We used the generalized additive model (GAM) to fit resource selection functions (Hastie and Tibshirani 1990). The response was the Common Quail’s occurrence. Eleven variables extracted by PCAs, geographical variables (longitude, latitude, altitude, and denivelation), NDVI from March to April, inorganic fertilizer input and the level of farmland mechanization were used as predictors. The most parsimonious model was selected with the use of Akaike information criterion (mgcv library in R; Wood 2013). We analyzed all possible models (using MuMIn library in R; Bartoń 2013), by adding or removing factors, linearizing or including them as a polynomial spline (Hastie and Tibshirani 1990). The binomial distribution of errors and the logit link function were applied. The correlation coefficient between the predicted vs. the observed occurrence (log-transformed) was used as a measure of error prediction (Hastie et al. 2008; Kuczyński et al. 2010). D 2 coefficient was used as a measure of deviance reduction (Kuczyński et al. 2010). According to these models, we created a predictive map of the Common Quail’s occurrence.

Results

Common Quail’s occupancy

The frequency of the Common Quail’s occurrence in grid cells varied significantly between the years of the study (2000: 32.5 %; 2001: 32.9 %; 2002: 27.6 %; 2003: 22.4 %; 2004: 25.9 %; 2005: 24.7 %; 2006: 23.4 %; 2007: 33.9 %; 2008: 28.4 %; 2009: 25.7 %, G (9) = 8.71, p < 0.001). The aggregated data for all the study years showed that the species was recorded at least once in 54.1 ± 0.18 % of all grid cells. The mean density (assuming perfect detectability) expressed as the sum of all birds seen or heard in the field in a single grid cell was 1.2 (95 % CI 1.1–1.3), while the mean density for occupied plots was only 2.3 (95 % CI 2.1–2.4) individuals/1 km2.

Habitat use

Of the 8,192 models analyzed, only six gained support using information-theoretic criteria, showing AIC weights >0 (Table 3). The most parsimonious model of the Common Quail’s occurrence (Table 3) included a smooth GAM fit to CFORFIELD, ALTITUDE, NDVMARCH, NDVJUNE, FERTILIZ, and a linear fit to MFORFIELD, PREC and LONGITUDE. D 2-coefficient of this model was 0.67 and it was better for describing the variation of the Quail’s occurrence than the second model (evidence ratio 1.30) in our candidate set, but ΔAIC between model no. 1 and no. 2 was only 0.53, suggesting that these models were highly competitive.

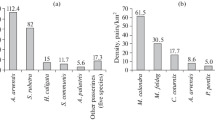

Model selection procedures allowed us to identify eight predictors with relative importance (RI) close to 1. All of them were included in the best-supported model. The most important predictors included two variables capturing main habitat gradients, i.e., CFORFIELD (RI = 0.999) and MFORFIELD (RI = 0.995). The former was characterized by non-linear while the latter by linear shape of the response function and represented a habitat gradient from coniferous forest (CFORFIELD, Table 4; Fig. 2a) or deciduous and mixed forest (MFORFIELD, Table 4; Fig. 2b) to non-irrigated arable fields and meadows. An equally important variable (RI = 0.999) was ALTITUDE, which revealed (Table 4; Fig. 2c) a non-linear shape of the response function with the Common Quail recorded up to 900 m a.s.l. The next variables in the model were NDVIMARCH (RI = 0.994; Table 4; Fig. 2d) and NDVIJUNE (RI = 0.972; Table 4; Fig. 2e). The species occurrence probabilities increased in areas where vegetation began early and photosynthetic activity continued for a relatively long time during the season. The seventh variable was PREC (RI = 0.994; Table 4; Fig. 2g), showing that the Common Quail appeared in areas where the rainfall was low. Next, there was FERTILIZ (RI = 0.995; Table 4; Fig. 2h) with a non-linear shape of the response function, which showed that the species did not avoid regions with a high level of mineral fertilization applied. The last factor included in the top model was LONGITUDE (RI = 0.991; Table 4; Fig. 2i), reflecting that the Common Quail’s occurrence increased from the west to the eastern parts of Poland.

GAM fit for the Common Quail’s occurrence. a CFORFIELD represented a habitat gradient from coniferous forest (c.forest) to non-irrigated arable fields (fields); b MFORFIELD represented a habitat gradient from deciduous and mixed forest (d.m.forest) to meadows and arable fields (field.mead); ALTITUDE represented a geographical gradient from area of low elevation (low) to area of high elevation (high); NDVIMARCH and NDVIJUNE reflect area where green vegetation in March and June is low (low) to area where vegetation in both months is high (high); PREC represented the level of precipitation (low)—areas with low level of precipitation, while (high)—areas with high level of precipitation; FERTILIZ high value of the component represented areas with a high level of inorganic fertilization (high), whereas low value of the component showing areas where use of fertilize is low (low). LONGITUDE represented geographical gradient from west (west) to east (east). The y-axis: probability of occurrence—(s) smoother function with estimate degrees of freedom in parenthesis (Hastie and Tibshirani 1990; Brown 2011). The shaded areas represent standard errors of the estimate curves

The second model (Table 3) in our candidate set included all predictors from model no. 1 as well as MIXFIEL (RI = 0.500) as an additional factor. The high probability of the Common Quail’s occurrence also depended on large areas of mixed arable fields.

Predictive mapping

On the basis of GAM models, we created a predictive map of the Common Quail’s occurrence (Fig. 3). The correlation coefficient between the predicted and the observed probability of occurrence was 0.59, (df = 722, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Patterns in habitat use

The aim of this study was to explore a relatively wide spectrum of environmental factors and identify variables responsible for the occurrence of breeding Common Quails in central Europe with Poland as an example. Unsurprisingly, the most important components of the environment that positively affected the species’ occurrence were the most popular forms of arable fields, i.e., large and non-irrigated arable fields and mixed arable fields. Thus, our findings are consistent with a host of earlier studies conducted on a small spatial scale, which revealed that the species preferred rather large arable fields with permanent crops, such as alfalfa, winter barley, and winter wheat as well as cultivated areas of a lesser extent with flax (Aubrais et al. 1986; Dyrcz et al. 1991; Bereszyński 1992; Cramp and Perrins 1994; George 1996; Guyomarc’h et al. 1998).

We also established that the predicted localizations of the species were situated both on lowlands and up to 900 m a.s.l. on highlands in southeastern parts of Poland, a finding that is consistent with results of other studies (Rodríguez-Teijeiro et al. 2009; Sardà-Palomera et al. 2012), showing frequent occurrence of Quails at relatively high altitudes. It does not necessarily reflect any topographic preferences of the species but may be explained by the late-season shift in breeding distribution caused by birds moving from early harvested lowland fields to still unreaped fields in upland localities in order to breed (Rodríguez-Teijeiro et al. 2009; Sardà-Palomera et al. 2012).

According to our study, quails prefer agricultural areas with high NDVI values at the beginning of spring and also areas where vegetation lasts a long time during a season. A similar pattern was found in Spain where the species preferred agricultural areas with a high level of NDVI, which reflected mature crops as a primary habitat (Sardà-Palomera et al. 2012). The observed correlation between the presence of quails and NDVI in June probably reflects the species’ affinity to sites with a high photosynthetic activity at the time when many cereals cease to grow (particularly in western Poland) and start to ripen. What is important, sites with high NDVI in March are not the sites with high NDVI in June (correlation between the two variables is relatively low: r = −0.27, n = 311664, p < 0.001), which is suggestive of a seasonal shift in quails’ habitat preferences, as it was noted in Spain (Sardà-Palomera et al. 2012). It is worth noticing that other species and also groups of species show similar preferences of the vegetation index, even though they are usually associated with other traditional farmland habitats. For example, the White Stork Ciconia ciconia prefers a high value of NDVI in June but only on meadows (Kosicki 2010), while the Yellowhammer Emberiza citrinella (Whittingham et al. 2005) and the Great Grey Shrike Lanius excubitor (Kuczyński et al. 2010) prefer mixed open habitats always with a high rate of NDVI (Bacaro et al. 2011). Furthermore, farmland “focal” bird species as well as total species richness also depend on the high value of NDVI (Sanderson et al. 2009; Bacaro et al. 2011; Kosicki and Chylarecki 2012). So, our study confirms the general pattern that a higher spectral index, in our case NDVI, corresponds to the higher probability of species occurrence even with respect to birds linked only to large-scale monoculture areas (Palmer et al. 2002).

We found that the probability of the Common Quail’s occurrence decreased with the increase of rainfall, which is contrary to results obtained by Puigcerver et al. (1998) in northeastern Spain, where rainfall positively affected the species’ occurrence. Nevertheless, the quail in Spain does not show a preference for high precipitation areas per se, but rather for areas where high precipitation enhances continued growth of vegetation as measured by high NDVI values. This is fully compatible with preferences we have identified for this species in Polish farmland. Moreover, our variable measuring precipitation is a principal component axis score having also high negative loadings with summer temperature (Table 1), meaning that quails prefer warmer regions, which is in agreement with the species’ thermal niche (Huntley et al. 2007).

The observed gradient of the increasing occurrence of Quails going from the west to the east part of Poland (see Fig. 3) can not be explained by known differences in NDVI, precipitation or altitude as these factors are controlled by their inclusion in the best model. However, we suspect that historical distribution of this species may play an important role. The heuristic comparison of our distribution maps with the Polish Breeding Bird Atlas (PBBA; years of study 1985–2004; Sikora et al. 2007) showed that the Quail as well as other farmland species were more widely distributed in central and eastern rather than in western Poland. The finding is consistent with the general pattern that bird diversity increases from western to eastern parts of Europe (Hagemaijer and Blair 1997). This relation was attributed to the traditional farmland use (Reif et al. 2008). Now, this picture could have changed, because another crucial discovery of our study is that the Common Quail did not avoid regions with a high level of fertilizer use, a fact that had not been previously reported for this species (Michaïlov 1995; Broyer 1996). The level of inorganic fertilizer use is a widely accepted indicator of agricultural intensity, mainly because of its impact on vegetation structure, cereal communities and reduced invertebrate diversity in cultivated fields (Batáry et al. 2008; Kleijn et al. 2009; Kovács-Hostyánszki et al. 2011a, b; Blüthgen et al. 2012). To complement this picture, Quails in our sample did not avoid areas with a high level of mechanization (this variable was not selected in any of the models analyzed).

Many studies have shown that excessive fertilizer use contributes to a reduction of farmland bird populations (Chamberlain and Fuller 2000; Donald et al. 2001). However, in some cases (e.g., Kovács-Hostyánszki et al. 2011b), the relationship between fertilizer use and the number of birds is not simply linear but rather unimodal, with avian abundance peaking at intermediate values of fertilizer input. Our study revealed that in regions where the quail was present, the average fertilizer use per hectare amounted to 87 (SD = 18) kg/nitrogen fertilizer/ha/year), which lies within the range of optimal values for the Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava and the quail in Hungary (60–100 kg/nitrogen fertilizer/ha/year, Kovács-Hostyánszki et al. 2011b), but well below the levels typically observed in the UK (250–300 kg/nitrogen fertilizer/ha/year) and the Netherlands (150–200 kg/nitrogen fertilizer/ha/year) (Chamberlain et al. 2002; Kleijn et al. 2006; Kovács-Hostyánszki et al. 2011b).

These results suggest that in Poland, and possibly other countries of central Europe, quails currently do not prefer traditional agriculture of low-intensity, which is contrary to other farmland bird species (Sanderson et al. 2009; Kosicki and Chylarecki 2012). Singing males of the Quail are more likely to occur in areas showing enhanced crop growth in spring and receiving higher input of mineral fertilizers. These can be classified as high-intensity agriculture within the central and eastern European domain, although possibly of medium-intensity by western European standards.

The adaptive value of observed habitat preferences

Given the apparent affinity of the quail to high-intensity agriculture in Poland, a crucial question arises as to whether this habitat choice is in fact adaptive, in other words, whether birds achieve high reproductive success in this area.

It is possible that quails are attracted to farmland with high fertilizer input due to certain preferred habitat features. Sustainable use of fertilizers enhances better quality of seeds, forming the basic component of granivorous birds’ diet. Then, many areas specializing in cereal production where high fertilizer input is noted tend to maintain agricultural productivity in a multi-annual cycle. Potentially, this practice positively affects quails because multi-annual stability of habitat conditions is an important element for migratory birds when they select their breeding habitats (Tryjanowski et al. 2005). On the other hand, luxuriant tall crops with high NDVI in April or in June, which are a consequence of sustainable fertilizer use, may be harvested too early, thus inhibiting appropriate chicks’ survival. In such a situation, arable land covered with fast-growing crops may effectively act as sink habitats or ecological traps not only for quails but also other species of Phasianidae, e.g., Grey Partridge (Robertson and Hutto 2006; Gilroy and Sutherland 2007; Schlaepfer et al. 2010). If quails breeding in temperate Europe in May and June are indeed individuals that breed earlier than in northern Africa or southern Europe, the persistence of maladaptive habitat choice in the population is even more likely. Proximate cues used by quails to identify good-quality habitats in northern Africa or Spain may be linked to ecological traps in Poland and possibly other countries of central and northern Europe, which are visited by the same birds later in the season. What is good in the first place may turn out bad in other breeding sites located in a different climatic zone. In this scenario, the conspecific attraction postulated as a mechanism explaining aggregated distribution of singing male quails (Guyomarc’h et al. 1998) may reinforce suboptimal habitat choice. It may be further enhanced by changes observed in agriculture, leading to an increased area of winter cereals and a faster growth of crops exposed to warmer springs (i.e., increasing extent of ecological traps). In fact, changing agricultural practices may particularly promote the existence of maladaptive habitat choice (Gilroy and Sutherland 2007; Gilroy et al. 2011). Obviously, to understand how the species actually fare in current farmland of temperate Europe, we badly need data on the breeding success of quails across different crop types.

Despite an apparently good fit of our prediction model, we should consider the methodological limitations of our study that are connected with data collection. The species is reported to be most active vocally in the evening, whereas field inspections were carried out early in the morning. So it is highly possible that the measured occurrence probabilities are underestimated and thereby the quail density is actually considerably higher than the obtained results show. Unfortunately, we do not have any other large-scale data that could help us assess the level of underestimation. However, unless males occurring in different habitats show distinctly different diurnal pattern of vocal activity, the patterns we identified should hold.

Additionally, due to the lack of actual measurements of fertilizer use in each grid cell, we applied regional values of their input. Although such an approach may increase the error in predictive models, it is unlikely to bias the observed results and affect general conclusions presented.

Conclusions

The Common Quail’s distribution in Polish farmland is shaped by several land-use, climatic, and geographic factors, as well as by the intensity of farmland management. By extending the set of predictor variables used in recent studies (Sardà-Palomera and Vieites 2011; Sardà-Palomera et al. 2012), we were able to create an improved model of habitat preferences of this species in central European farmland landscapes. Among the analyzed anthropogenic features, inorganic fertilizer input is an important factor, which can positively affect the probability of the species’ occurrence. Consequently, the quail may prefer habitats typical for medium and high-intensity agriculture, in contrast to many farmland bird species.

Further research is needed to quantify costs and benefits of this habitat choice. However, our results indicate that currently the quail cannot be used as a species indicative of traditional or low-intensity agriculture.

References

Aubrais O, Hémon YA, Guymarc’h JC (1986) Habitat et occupation de l’espace chez la caille des blés (Coturnix coturnix coturnix) au début de la période de reproduction. Gibier Faune Sauvage 3:317–342

Bacaro G, Santi E, Rocchini D, Pezzo F, Puglisi L, Chiarucci A (2011) Geostatistical modelling of regional bird species richness: exploring environmental proxies for conservation purpose. Biodivers Conserv 20:1677–1694

Bartoń K (2013) MuMIn: multi-model inference. R package version 1.9.0. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn

Batáry P, Kovács A, Báldi A (2008) Management effects on carabid beetles and spiders in central Hungarian grasslands and cereal fields. Community Ecol 9:247–254

Benton TG (2007) Managing farming’s footprint on biodiversity. Science 315:341–342

Benton TG, Bryant DM, Cole L, Crick HQ (2002) Linking agricultural practice to insect and bird populations: a historical study over three decades. J Appl Ecol 39:673–687

Bereszyński A (1992) Metodyka oraz wyniki badan ilościowych i ekologii przepiórki Coturnix coturnix (L.) na wybranych powierzchniach badawczych północno-zachodniej o zachodniej Polski w latach 1987–1989. In: Górski W, Pinowski J (eds) Dynamika populacji ptaków i czynniki ją warunkujące. WSP. Słupsk, pp 79–83 (in Polish)

BirdLife International (2004) Birds in Europe: population estimates, trends and conservation status. BirdLife International, Cambridge

Blüthgen N, Dormann CF, Prati D, Klaus VH, Kleinebecker T, Hölzel N, Alt F, Boch S, Gockel S, Hemp A, Müller J, Nieschulze J, Renner SC, Schöning I, Schumacher U, Socher SA, Wells K, Birkhofer K, Buscot F, Oelmann Y, Rothenwöhrer C, Scherber C, Tscharntke T, Weiner CN, Fischer M, Kalko EKV, Linsenmair KE, Schulze ED, Weisser WW (2012) A quantitative index of land-use intensity in grasslands: integrating mowing, grazing and fertilization. Basic Appl Ecol 13:207–220

Brown GS (2011) Patterns and causes of demographic variation in a harvested moose population: evidence for the effects of climate and density-dependent drivers. J Anim Ecol 80:1288–1298

Broyer J (1996) Les “fenaisons centrifuges”, une méthode pour réduire la mortalité des jeunes râles de genêts Crex crex et des cailles des blés Coturnix coturnix. Rev Ecol (Terre Vie) 3:269–276

Butler SJ, Boccaccio L, Gregory RD, Vorisek P, Norris K (2010) Quantifying the impact of land-use change to European farmland bird populations. Agric Ecosyst Environ 137:348–357

Chamberlain DE, Fuller RJ (2000) Local extinctions and changes in species richness of lowland farmland birds in England and Wales in relation to recent changes in agricultural land-use. Agric Ecosyst Environ 78:1–17

Chamberlain DE, Fuller RJ, Bunce RGH, Duckworth JC, Shrubb M (2002) Changes in the abundance of farmland birds in relation to the timing of agricultural intensification in England and Wales. J Appl Ecol 37:771–788

Chylarecki P, Jawińska D (2007) Monitoring Pospolitych Ptaków Lęgowych. Raport z lat 2005–2006. OTOP Warszawa (in Polish)

Cramp S, Perrins CM (eds) (1994) The birds of the Western Palearctic, vol 9. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Doll CNH, Muller J-P, Morley JG (2007) Mapping regional economic activity from night-time light satellite imagery. Ecol Econ 57:75–92

Donald PF, Green RE, Heath MF (2001) Agricultural intensification and the collapse of Europe’s farmland bird populations. Proc Roy Soc B Biol Sci 268:25–29

Donald PF, Sanderson FJ, Burfield IJ, van Bommel FPJ (2006) Further evidence of continent-wide impacts of agricultural intensification on European farmland birds, 1990–2000. Agric Ecosyst Environ 116:189–196

Dyrcz A, Grabiński W, Stawarczyk T, Witkowski J (1991) Ptaki śląska. Monografia faunistyczna. Uniwersytet wrocławski Wrocław, pp 526 (in Polish)

European Commission, EC (2009) European Union Management Plan 2009–2011. Common Quail Coturnix coturnix. Technical Report 2009-032. European Communities

Fox AD (2005) Has Danish agriculture maintained farmland bird populations? J Appl Ecol 41:427–439

Franklin J (2009) Mapping species distributions. Spatial inference and prediction. Cambridge University Press, London

Gallego S, Puigcerver M, Rodríguez-Teijeiro JD (1997) Quail Coturnix coturnix. In: Hagemeijer WJM, Blair MJ (eds) The EBCC atlas of European breeding birds: their distribution and abundance. T & A. D. Poyser, London, pp 214–215

George K (1996) Habitat use, density and population changes of Quail Coturnix coturnix in Sachsen-Anhalt, Germany. Vogelwelt 117:205–211

Gilroy JJ, Sutherland WJ (2007) Beyond ecological traps: perceptual errors and undervalued resources. Trends Ecol Evol 22:351–356

Gilroy JJ, Anderson GQA, Vickery JA, Grice PV, Sutherland WJ (2011) Identifying mismatches between habitat selection and habitat quality in a ground-nesting farmland bird. Anim Conserv 14:620–629

Gregory RD, Noble DA, Custance J (2004) The state of play of farmland birds: population trends and conservation status of farmland birds in the United Kingdom. Ibis 146(Suppl. 2):1–13

Gregory RD, Van Strien AJ, Vorisek P, Gmelig Meyling AW, Noble DG, Foppen RBP, Gibbons DW (2005) Developing indicators for European birds. Philos T R Soc B 360:269–288

Guyomarc’h C, Combreau O, Pugicerver M, Fontoura P, Aebischer NJ, Wallace DIM (1998) Coturnix coturnix Quail. BWP Update 2:27–46

Hagemaijer WJM, Blair MJ (1997) The EBCC atlas of European breeding birds: their distribution and abundance. T & A. D. Poyser, London

Hastie T, Tibshirani R (1990) Generalized additive models. Chapman and Hall, London

Hastie T, Tibshirani RJ, Friedman J (2008) The elements of statistical learning, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York

Heiberger RM (2013) Statistical Analysis and Data Display: Heiberger and Holland. R package version 2.3-37. http://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/HH

Herrmann M, Dassow A (2006) Quail Coturnix coturnix. In: Flade M, Plachter H, Schmidt R, Werner A (eds.) Nature conservation in agricultural ecosystems: results of the Schorfheide-Chorin Research Project. Quelle & Meyer Verlag, Wiebelsheim, pp 194–203

Huntley B, Green RE, Collingham YC, Willis SG (2007) A climatic atlas of European breeding birds. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona

Kleijn D, Baquero RA, Clough Y, Díaz M, DeEsteban J, Fernández F, Gabriel D, Herzog F, Holzschuh A, Jöhl R, Knop E, Kruess A, Marshall EJP, Steffan-Dewenter I, Tscharntke T, Verhulst J, West TM, Yela JL (2006) Mixed biodiversity benefits of agrienvironment schemes in five European countries. Ecol Lett 9:243–254

Kleijn D, Kohler F, Báldi A, Batáry P, Concepción ED, Clough Y, Díaz M, Gabriel D, Holzschuh A, Knop E, Kovács A, Marshall EJ, Tscharntke T, Verhulst J (2009) On the relationship between farmland biodiversity and land-use intensity in Europe. Proc Roy Soc B Biol Sci 276:903–909

Kosicki JZ (2010) Reproductive success of the White Stork Ciconia ciconia population in intensively cultivated farmlands in western Poland. Ardeola 57:243–255

Kosicki JZ, Chylarecki P (2012) Effect of climate, topography and habitat on species-richness of breeding birds in Poland. Basic Appl Ecol 13:475–483

Kovács-Hostyánszki A, Batáry P, Báldi A, Harnos A (2011a) Interaction of local and landscape features in the conservation of Hungarian arable weed diversity. Appl Veg Sci 14:40–48

Kovács-Hostyánszki A, Batáry P, Pach WJ, Báldi A (2011b) Effect of fertilizer application on summer usage of cereal fields by farmland birds in central Hungary. Bird Study 58:330–337

Krebs JR, Wilson JD, Bradbury RB, Siriwardena GM (1999) The second silent spring? Nature 400:611–612

Kuczyński L, Chylarecki P (2012) Atlas of common breeding birds in Poland: distribution, habitat preferences and population trends. GIOŚ, Warszawa

Kuczyński L, Antczak M, Czechowski P, Grzybek J, Jerzak L, Zabłocki P, Tryjanowski P (2010) A large-scale survey of the great grey shrike Lanius excubitor in Poland: breeding densities, habitat use and population trends. Ann Zool Fenn 47:67–78

Michaïlov C (1995) A study on the ecology and biology of quail (Coturnix coturnix L.) in the high plains of southwestern Bulgaria. Thesis Dissertation, The Higher Institute of Forestry and Wood Technology, Sofia (in Bulgarian)

Neteler M, Mitasova H (2008) Open source GIS: a GRASS GIS approach, 3rd edn. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York

Newton I (2004) The recent declines of farmland bird populations in Britain: an appraisal of causal factors and conservation actions. Ibis 146:579–600

O’Brien RM (2007) A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant 41:673–690

Palmer MW, Earls P, Hoagland BW, White PS, Wohlgemuth T (2002) Quantitative tools for perfecting species lists. Environmetrics 13:121–137

Puigcerver M, Rodriguex-Teijeiro JD, Gallego S (1998) The effect of rainfall on wild population of Common Quail (Coturnix coturnix). J Ornithol 140:335–340

Quinn GP, Keough MJ (2002) Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

R Development Core Team (2010) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Reif J, Voříšek P, Šťastný K, Bejček V, Petr J (2008) Agricultural intensification and farmland birds: new insights from a central European country. Ibis 150:569–605

Robertson BA, Hutto RL (2006) A framework for understanding ecological traps and an evaluation of existing evidence. Ecology 87:1075–1085

Rodríguez-Teijeiro JD, Sardà-Palomera F, Nadal J, Ferrer X, Ponz C, Puigcerver M (2009) The effects of mowing and agricultural landscape management on population movements of the common quail. J Biogeogr 36:1891–1898

Royle JA, Chandler RB, Yackulic C, Nichols JD (2012) Likelihood analysis of species occurrence probability from presence-only data for modelling species distributions. Methods Ecol Evol 3:545–554

Sanderson FJ, Kloch A, Sachanowicz K, Donald PF (2009) Predicting the effect of agricultural change on farmland bird populations in Poland. Agric Ecosyst Environ 129:37–42

Sardà-Palomera F, Vieites DR (2011) Modelling species’ climatic distributions under habitat constraints: a case study with Coturnix coturnix. Ann Zool Fenn 48:147–160

Sardà-Palomera F, Puigcerver M, Brotons L, Rodríguez-Teijeiro JD (2012) Modelling seasonal changes in the distribution of Common quail Coturnix coturnix in farmland landscapes using remote sensing. Ibis 154:703–713

Schlaepfer MA, Sherman PW, Runge MC (2010) Decision making, environmental change, and population persistence. In: Westneat DF, Fox CW (eds) Evolutionary behavioral ecology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 506–515

Sikora A, Rohde Z, Gromadzki M, Neubauer G, Chylarecki P (2007) Polski Atlas Ornitologiczny. Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Poznan

Small C, Pozzi F, Elvidge CD (2005) Spatial analysis of global urban extent from DMSP-OLS nighttime lights. Remote Sens Environ 96:277–291

Tryjanowski P, Jerzak L, Radkiewicz J (2005) Effect of water level and livestock on the productivity and numbers of breeding White Storks. Waterbirds 28:378–382

Tryjanowski P, Hartel T, Baldi A, Szymański P, Tobolka M, Herzon I, Goławski A, Konvicka M, Hromada M, Jerzak L, Kujawa K, Lenda M, Orłowski G, Panek M, Skórka P, Sparks TH, Tworek S, Wuczyński A, Żmihorski M (2011) Conservation of farmland birds faces different challenges in Western and Central-Eastern Europe. Acta Orn 46:1–12

Van Strien AJ, Soldaat LL, Gregory RD (2012) Desirable mathematical properties of indicators for biodiversity change. Ecol Indic 14:202–208

Whittingham MJ, Swetnam RD, Wilson JD, Chamberlain DE, Freckleton RP (2005) Habitat selection by yellowhammers Emberiza citrinella on lowland farmland at two spatial scales: implications for conservation management. J Appl Ecol 42:270–280

Wilson JD, Evans AD, Grice PV (2009) Bird conservation and agriculture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wood S (2013) mgcv: mixed GAM computation vehicle with GCV/AIC/REML smoothness estimation. R package version 1.7-22. http://cran.rproject.org/web/packages/mgcv

Wretenberg J, Lindstrom A, Svensson S, Thierfelder T, Part T (2006) Population trends of farmland birds in Sweden and England: similar trends but different patterns of agricultural intensification. J Appl Ecol 43:1110–1120

Wretenberg J, Lindstrom A, Svensson S, Part T (2007) Linking agricultural policies to population trends of Swedish farmland birds in different agricultural regions. J Appl Ecol 44:933–941

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to numerous observers who collected data in the field. The full list of their names can be found at http://main5.amu.edu.pl/~kubako/tsr/. We want to thank Justyna Grześkowiak for her linguistic assistance. The Polish Common Breeding Bird monitoring project was funded by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (UK), United Nations’ GEF Small Grant Programme, European Commission (The Cooperation Fund), Polish Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (GIOŚ) and National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management (NFOŚiGW), and coordinated by the Museum and Institute of Zoology Polish Academy of Sciences and the Polish Society for the Protection of Birds (OTOP). The study has been supported by MNiSW grant No. N304 025936 to JZK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kosicki, J.Z., Chylarecki, P. & Zduniak, P. Factors affecting Common Quail’s Coturnix coturnix occurrence in farmland of Poland: is agriculture intensity important?. Ecol Res 29, 21–32 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-013-1093-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-013-1093-2