Abstract

The rise and global reach of the corporate foundation (CF) phenomenon has attracted the attention of academic researchers and practitioners and led to a plurality of definitions and understandings. This definitional fuzziness notwithstanding, the term hybridity is widely used as the defining characteristic to describe a CF’s position between business and civil society and its diverse interlinkages with its founding company. However, the extant literature has seldom explained what hybridity signifies, when it occurs and how it is shown. This paper presents the findings of a systematic review of the academic and gray literature on CFs. Based on 80 publications covering 30 countries worldwide, this study proposes 15 characteristics along four global themes as a comprehensive set to account for the complexity of CFs. It develops propositions for a fine-grained understanding of what constitutes the hybrid nature of CFs at the strategic, organizational and contextual levels. Accordingly, this study suggests ways forward by revealing questions that require further research toward a better understanding of the CF phenomenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corporate foundations (CFs) are increasingly visible in the philanthropic landscape of charitable foundations (Pedrini and Minciullo 2011; Rey-Garcia 2012), and they are becoming increasingly important for the philanthropic activities of large corporations (Minefee et al. 2015). Their international spread has increased over the last few years, as they appear in foundation sectors worldwide as a modest but significant group (Monfort et al. 2021). For instance, in France, 20% of all foundations are considered to be CFs (Ernst & Young Société d’Avocats and Les entreprises pour la Cité 2014) and also in China's rapidly developing philanthropic sector CFs accounted for 19.7% of all foundations in 2016, although many of them have only been established in recent years (He and Wang 2020). Beyond their global presence, CFs themselves have also tended to expand their activities on a global scale and operate more internationally (Altuntas and Turker 2015). For example, an increasing number of multinational companies, such as Vodafone Group Plc, are establishing local branches of foundations in the countries where they operate, in addition to the original CF, which is often located in the country of the company’s headquarters (Gehringer and Schnurbein 2020).

With the rise and global reach of CFs, academic researchers and practitioners have shown increasing interest in the CF phenomenon. Although the overall quantity of available publications on CFs is still limited (Roza et al., 2020), a growing number of peer-reviewed studies, sector reports and magazine articles inform the discourse. Parallel to this development, an increase in the number of definitions of CFs can be observed. These reflect the diversity of approaches and organizational structures among corporate-related foundations, embedded in their particular legislative framework and sociopolitical context.

For example, in the European tradition, CFs have been defined as separately constituted foundations with a company as a donor offering annual gifts, which the foundation distributes “either through grantmaking or through operational programmes, or a combination of the two” and where “the majority of trustees of the governing board are employees or board members of, or individuals retired from, the donor company” (European Foundation Centre 2003: 5). The European Foundation Centre also recognizes charitable industrial foundations (also called shareholder foundations); these foundations “have a charitable goal, but just happen to also own a controlling interest in one or more business companies” (Thomsen 2012). This alternative corporate-related foundation form deviates from conventional CFs, as charitable industrial foundations “face situations of increased governance complexity stemming from their ownership status” (Bothello et al. 2020). Continental Europe, especially Denmark, is home to some of the oldest of these foundations (Prophil 2015; Thomsen 2012). Scholars argue that conceptualizations of CFs should encompass both foundations “that are governed under corporate control and/or obtain the majority of their resources from the firm” (Rey-Garcia et al. 2018: 517).

In contrast to continental Europe, this type does not exist in Anglo-Saxon countries due to legal restrictions or societal disapproval (Bothello et al. 2020). In the USA, CFs are not recognized as public charities but as private foundations, and therefore, they are subject to much more restrictive tax regulations and reporting requirements (Candid 2020; Tremblay-Boire 2020). Other conceptualizations of CFs are known in Latin American countries, where the US way of conceptualization is applicable only on a limited basis, as researchers argue (Rey-Garcia et al. 2020).

The plurality of definitions and the growing diversity of CF types are problematic because researchers and practitioners are increasingly losing track of the characteristics that determine which organizations to include in or exclude from the group of CFs. The lack of consistent conceptualizations has already been recognized by extant research as a conceptual barrier to advancing knowledge on CFs (Rey-Garcia et al. 2018). The definitional fuzziness of the CF phenomenon on a global level notwithstanding, previous research has noted certain similarities across countries and regions (Corporate Citizenship 2014). More importantly, most conceptualizations agree on one fundamental element that corporate-related foundations share: Hybridity is seen as essential to the nature of CFs (e.g., Minciullo 2016; Rey-Garcia et al. 2018; Walker 2013). The extant nonprofit literature perceives them as hybrid organizations because, as both nonprofit organizations and institutionalized forms of their founders’ philanthropic commitment, they possess diverse roots and links to business and civil society.

However, what is missing in these perceptions of hybridity in CFs is a detailed understanding of the configurations of the characteristics leading to different patterns of hybridity. This knowledge gap is based on two assumptions. First, hybridity may not be a static condition to which all types of CFs are exposed in the same way. Rather, CFs may show different patterns, which might even occur at the same time in different constellations. Second, these patterns may exist due to the interplay of key characteristics of CFs and may not be caused only by contrary intentions or the corporate origin of resources. In fact, these two causes of hybridity have long been addressed and discussed in the CF literature. To date, most studies in organizational theory have focused on completely independent organizations, such as social enterprises, as ideal hybrid organizations (Wolf and Mair 2019). Little is known about hybridity in other organizational forms that might not be entirely independent, such as CFs.

To address these issues, this study conducts a systematic literature review of the academic and gray literature to provide both a comprehensive attribute space of CF characteristics and propositions regarding their hybrid nature. The review is guided by the following two questions:

Research question 1 Which characteristics have been used in the extant literature to describe CF types?

Research question 2 Which configurations of characteristics are key for the patterns of hybridity in CFs?

This review makes a twofold contribution to the literature. First, on an empirical level, it combines a range of 80 different academic and practitioner-driven publications on the topic of CFs, covering 30 countries around the world. By synthesizing the different ways CFs have been conceptualized to date, it offers a comprehensive perspective on CF along four global themes. The quantitative analysis provides novel insights into the relative importance of sets of characteristics for hybridity on three levels. Second, on a theoretical level, the review combines the current state of knowledge on organizational hybridity and CFs’ hybrid nature. It offers a first step toward a narrative on the hybridity of CFs and suggests ways forward by developing three propositions and revealing questions that require further research toward a better understanding of the CF phenomenon.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 summarizes the current theoretical understanding of CFs and organizational hybridity. Section 3 provides a description of the publications and methods used in this review. Section 4 presents the findings for each of the two research questions, and Sect. 5 discusses their implications for future research. The paper concludes by explaining the limitations of the review and its contribution to the topic of hybridity in CFs as an important yet neglected issue.

Theoretical Background

Corporate Foundations

As organizations, CFs are described in scholarship in various ways. Coupling the actually observable diversity of CFs worldwide and even within the borders of a single country leads to a fuzziness of definitions and concepts, which gives room to the perception of CFs as elusive organizations that occupy an undefined space between the market and civil society.

Research itself faces the challenge of translation and equivalence of the term ‘corporate foundation’ across different languages and national or institutional contexts. Regional- and country-specific traditions, regulations or norms have created linguistic diversity, which, for example, in English, includes the terms company-sponsored foundation, family business foundation, company-affiliated foundation, corporate fund and collective corporate foundation. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether one has to understand the same thing and, if not, how exactly to distinguish them from each other.

Collective CFs are a form of corporate philanthropy where several companies with shared interests join a collective initiative and form a corporate donor-to-donor collaboration (Maas 2020). Company-affiliated foundations are CFs that are either directly involved with the operation of a company (company-supporting foundations) or indirectly involved, by holding a substantial portion or all the shares of one or several companies or of another legal entity that runs a corporation (company-holding foundations) (Sprecher et al. 2016). From a civil society perspective, this legal distinction along ownership structures is not helpful because a foundation’s purpose can be charitable, purely economic or a combination of both (Gehringer 2018).

For the purposes of this study, a conceptualization of CFs is adopted that acknowledges CFs hybridity of governance and management, e.g., resources and organizational capabilities, and the fact that they can be established by a variety of founding bodies of which the CF might be also the owner or majority stockholder. Thus, CFs are defined as “those foundations (organizations with nonprofit status, own legal personality, and no members) that are governed under corporate control and/or obtain the majority of their resources from the firm” (Rey-Garcia et al. 2018: 517).

Hybridity in the Literature on Corporate Foundations

Many authors cite hybridity as a characteristic of CFs. Their arguments fall into three broad categories: First, the majority of authors use hybridity to convey the interconnectedness between the founding company and the CF. More specifically, arguments revolve around governance, human resources and financing issues. Sloane et al. (2003) refer their understanding of hybridity to six foundation attributes. These authors believe that if CFs fulfill all of them, they have an “ideal foundation model which is both independent from, and integrated with, the parent company” (Sloane et al., 2003: 3). In parallel, Rey-Garcia et al. (2018) call the hybrid nature of CFs a specific feature of these institutions due to their not-for-profit organizational form, their charitable purpose, their funding model involving a for-profit company and aspects of their governance. Hirsch et al. (2016) call CFs hybrid if, unlike in the case of “classic” CFs, not just one company but other institutions such as employee associations, public institutions and other companies were involved in the foundation process.

Second, a smaller group of authors relate hybridity to the CF environment and its various stakeholders. Accordingly, CFs “operate in two worlds: the business world and the foundation/nonprofit sector. As such, they appear to be responsive to pressures emanating from sets of peers in each of those inter-organizational communities” (Walker 2013: 5). Other scholars even say that due to their hybrid nature, CFs are “nonprofit bodies within a for-profit context” (Minciullo 2016: 223), which is why their “configuration […] appears to be more similar to firms’ subsidiaries rather than to nonprofit organizations” (Minciullo 2016: 216). More specifically, authors explore the impact of the tax or legal framework (Webb 1994), the dynamics of country-specific NPOs (Zhou 2015) and the industry sector in which the founding company is located (Peterson and Su 2017).

Finally, a small number of researchers associate hybridity with CFs since they have a “position at the boundary of several sectors” (Herlin and Pedersen 2013: 60). Therefore, they “incorporate elements from different institutional logics” (Pache and Santos 2013: 972), which leads to the “need to find ways to deal with the multiple demands to which they are exposed” (ibid). In the case of CFs, these are primarily the social welfare logic—having a charitable purpose—and the market logic—being “funded by one or several profit-maximizing, private-benefit purpose entities” (Rey-Garcia et al. 2018: 517). This gives CFs a “bridge building capacity between different societal groups” (Bethmann and Schnurbein 2015: 24) and “the potential to conduct important boundary work and facilitate collaborative action between the founding company and its external stakeholders” (Herlin and Pedersen 2013: 60).

Rethinking Hybridity in the Corporate Foundation Context

As a concept, hybridity has been linked with different interpretations and meanings in scholarship (Jäger and Schröer 2014; Smith 2014). On the one hand, researchers have questioned whether hybridity itself is not an “inevitable and permanent characteristic” (Brandsen et al. 2005: 758) of the third sector. The underlying idea is that the boundaries between the third sector, the market, the community and the state are increasingly blurred and dissolving. Thus, fuzzy and hybrid arrangements exist that ultimately lead to a reframing of the third sector concept. In this vein, the third sector is perceived as the “central area of society wherein tensions between competing values and methods of coordination are exacerbated or resolved, in a more or less complex portfolio that inevitably has to combine the various rationalities and mechanisms relevant for the production of social services and goods” (Brandsen et al. 2005: 761). On the other hand, this has led nonprofit researchers to focus on the “fuzziest cases, those that can be found on the fringes of the domain” (Brandsen et al. 2005: 762). In the past, these were mainly social enterprises, but recently, new instruments such as donor-advised funds (DAFs) have also attracted attention (Smith 2016).

In general, the literature refers to hybridity when two or more institutional logics are combined in one organization (Billis 2010). In other words, hybridization is described “as a process in which plural logics and thus actor identities are in play within an organization, leading to a number of possible organizational outcomes” (Skelcher and Smith 2015: 434). Institutional logics are understood “as taken-for granted beliefs and practices that guide actors’ behaviour in fields of activity” (Battilana and Lee 2014: 402). From this perspective, hybrid organizations do not just combine the sectoral characteristics of the market, government and the nonprofit community. Rather, they blend those multiple competing institutional logics in various ways (Pache and Santos 2013) to create clearly distinguishable hybrid types (Smith 2014). Battilana and Lee (2014: 398) propose that the constructs of organizational identity, organizational forms and institutional logics are interwoven and that their simultaneous appearance is reflected in the idea of hybrid organizing: “the activities, structures, processes, and meanings by which organizations make sense of and combine aspects of multiple organizational forms.” However, the hybridity literature is often too narrowly focused on independent organizations and rarely applies the concept to organizational forms other than social enterprises (Jäger and Schröer 2014). CFs thus represent an interesting case of an organization with coexisting institutional logics that is not completely independent and that has been little researched to date (Roza et al. 2020). In fact, CFs are a very typical hybrid structure in that they “often need to manage different logics such as a market logic tied to the strategic direction of the company and the needs of the community or citizenry, broadly defined” (Smith 2016: 328).

This paper argues that the combination of different institutional logics in CFs is based on the characteristics of three different, more or less simultaneously emerging dimensions. This distinction is based on the framework proposed by Jung et al. (2018), in which foundations are differentiated on the basis of characteristics from strategic, organizational and contextual dimensions. According to these authors, "they serve to demonstrate foundations' pan-domain situation—across markets, states, and nonprofits—rather than just ‘nonprofitness’” (Jung et al. 2018: 13). At the strategic level, “questions of foundations’ style, approach, span, and beneficiaries emerge” (Jung et al. 2018: 11). At the organizational level, “issues of lifespan, governance structure, age, resources, and size” (ibid) arise. These include the degree of formalization in organizational decision-making, communication and reporting, as well as the centralization and complexity of administrative processes (Fiss 2011). The contextual level refers to “themes of legal and socio-political settings and foundations’ links and origins” (Jung et al. 2018: 11): more precisely, the links to the market, government and the community sector and any technical or institutional changes that affect the work of CFs.

Methods

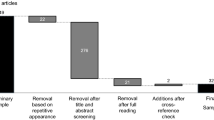

To examine the interplay between different CF characteristics and hybridity levels, 80 relevant publications describing CFs, based on the working definition of this study, were analyzed. The publications were selected following the critical literature review approach (Grant and Booth 2009), taking into account both the academic and gray literature (GreyNet 2018). To identify academic publications, 19 journals in philanthropic studiesFootnote 1 and eight major scholarly databasesFootnote 2 were systematically searched for articles in peer-reviewed journals, academic books and book chapters. As sources for gray publications such as academic dissertations, working papers, conference papers, institutional reports, consultant reports and magazine articles, the Google web search engine was used. The main search terms were corporate foundation and company-related foundation, used separately and each in combination with corporate philanthropy, corporate giving, corporate donation, corporate contribution and corporate gift. The main criterion for inclusion in our sample was an explicit focus on CFs, which, e.g., had to be reflected in the data sample of the publications. The publications had to be in English, but due to their relevance, 14 publications in German were included in the sample. Searching the reference list of each publication led to additional publications, which were added to the sample if they met the selection criteria and were not previously captured. The “closing date” for the review was December 31, 2018. Through this systematic and critical review process, 46 academic and 34 Gy items were identified.

Three aspects of the sample are noteworthy: First, the number of publications per year with CFs as the main topic shows that this is a rather young field of research, as most publications (80%) have been published since 2010 (Fig. 1). The high number of gray literature publications indicates the importance of the topic from a practical perspective.

Second, in terms of the countries covered in the 80 publications, CFs have been studied in 30 different countries worldwide (Fig. 2). However, only a fraction of them, namely the USA, the UK and Germany, are of recurrent interest. Overall, European countries and the USA are well represented, but knowledge on CFs in Africa, Latin America and Australia/Oceania is lacking. While academic publications mainly cover CFs in the USA, the gray literature uses a more diverse set of countries for data acquisition; however, most of them are in Europe. For example, the USA is the most analyzed country in the academic literature (14 times), in contrast to the UK (15 times) and Germany (12 times), which are the most frequently analyzed countries in the gray literature.

Third, ten of the 46 academic publications are books or book chapters. The remaining 36 publications appeared in journals in business (21), nonprofit studies (8) and social and political science (7). The figures suggest a bias toward the field of business, but it should be noted that journals in this field focus on a wide range of themes, including accounting, financial management, business ethics, corporate citizenship and innovation and entrepreneurship.

The analysis proceeded in four stages based on Schreier’s (2014) approach to qualitative content analysis (Fig. 3). The first stage builds the coding frame from a smaller nonprobability sample reflecting the main characteristics of the total sample of 80 publications. A stratified purposive sampling technique was used for the selection of ten publications (Ritchie et al. 2014). The selection criteria ensured a balance of academic and gray literature (five publications each), the coverage of a relatively broad time period (2001–2018) and the representation of variation in terms of the publication type and geographic region within these two groups. This criterion-based approach was important both to enhance the robustness of the coding frame and to ensure that the diversity in the perception of CFs between academic and gray publications could be explored. The thematic network technique (Attride-Stirling 2001) was applied to these ten publications to identify the criteria that the authors used to describe CFs. This technique allows thematic analyses of textual data to be structured by creating web-like networks that represent the systematic extraction of themes salient in a text at different levels. According to Attride-Stirling (2001), these networks are usually structured in (1) the most basic themes, (2) organizing themes that group similar basic themes into clusters and summarize them into more abstract principles and (3) global themes that summarize and interpret several organizing themes on a superordinate level representing the core of a thematic network. In total, the technique resulted in four networks, which were each discussed and revised with a research associate for consistency and clarity. Once the thematic networks were constructed, they served as the coding frame for the main analysis in the second stage.

In the second stage, all 80 publications were deductively coded along the basic themes of the coding frame. The coding frame was iteratively refined until all of the organizing themes comprehensively represented all of the basic themes, just like the global themes represented the organizing themes. This process led to the “attribute space” (Kuckartz 2010: 103) of CFs structured into four global themes, 15 organizing themes representing the main characteristics along which CFs were described in the extant literature and 54 basic themes representing possible specifications of each characteristic (Fig. 4). The coding in the first and second stages was performed with the program MAXQDA 18.0.8. This software is used for qualitative data analysis and is appropriate for encoding a large amount of text, comparing the encoded text passages without detaching them from their context, and preparing them for the next steps of analysis (Fiss 2011; Kuckartz 2010).

At the third stage, each of the 80 documents was once again binary coded to examine which of the 15 characteristics from the attribute space the authors used in their study to describe CFs (either 1 for present or 0 for not present). Similar coding was undertaken in parallel for each publication to identify on which of the three levels, i.e., strategic, organizational and contextual, the authors considered CFs to be hybrid organizations. This procedure generated an intersection table indicating for each publication in the sample (rows) the set of CF characteristics present and their relationship with one or more hybridity levels (columns).

Building on the intersection table, a quantitative analysis in the fourth stage compared the coding frequencies between CF characteristics and hybridity levels to detect the similarities and differences between them. The results from this research process are presented below in the order of the two research questions.

Results

Characteristics

The first research question asked: Which characteristics have been used in the extant literature to describe CF types? The descriptions of CFs usually cover, to varying degrees, the characteristics of four overarching themes: establishment, organizational capabilities, purpose and outcome. Figure 4 visualizes the structure of this attribute space, starting from the four global themes in the first circle and going outward to the 15 characteristics in the second circle and further outward to the 54 basic themes of the characteristics in the third circle. Together, they present the spectrum of possible descriptors of different CF types known today in the literature.

In the following, each theme and its characteristics are presented. The respective figures provide the percentages of coverage in the sample and the selected sources from the academic and gray literature.

-

(1)

Establishment

Under the first global theme, establishment, four characteristics are summarized (see Fig. 5). These characteristics are determined at the actual moment of creation or, in case of the founders’ intention, lead to the creation of a CF in the first place. According to previous research, the effects of the decisions made at this point in time on subsequent organizational structures and funding practices are particularly relevant.

According to the analysis, a wide variety of founding bodies is possible. Most publications (74%) relate their CF description to a corporate founding body, more precisely to either a listed or unlisted company, a family business or a public-law company. Although they are mentioned less frequently, the analysis shows that other donors are possible, such as private (19%) or institutional (8%) donors. Private founding bodies can be, for example, the company’s founding family, the company owner, employees or corporate executives, whereas a group of several companies, a co-partnership between a company and a governmental body or a partnership between a company and a private person are mentioned as institutional donors. An example of the latter can be found in Hirsch et al. (2016), who define a charitable foundation that was founded by 23 companies, one business association and one employer association as a CF.

The analysis showed that the establishment of a CF can be roughly assigned to three different intentions, mainly for corporate (78%) and/or societal (66%) reasons and sometimes, although rarely, due to temporal occasions (23%). When authors discuss an intention primarily in favor of the related company, they mean that the CF serves the purpose of relationship management with employees or customers, helps to professionalize the company’s social commitment and contributes to the development of the business. If, by contrast, they speak of a primarily societal intention, they describe founders who want to increase social well-being and promote social innovation and who feel a strong sense of societal responsibility. A temporal occasion describes the motivation to establish a CF due to company anniversaries, succession planning or other major reorganizations. Sloane et al. (2003: 7) give the example of “companies who have merged, de-mutualized or grown very fast by acquisition and, in the process, have established foundations endowed with shares in the new company and/or an annual dividend or percentage of pre-tax profits.”

Legal matters at the time at which a CF is set up revolve around the autonomy (59%), which refers to whether a foundation is legally independent or legally dependent, i.e., part of a donor-advised fund. The foundation type (54%) is charitable in the case of classic CFs but can be twofold, as in the case of shareholder foundations. In addition to supporting social issues that benefit the public good, shareholder foundations are endowed with shares that may allow them to exercise a degree of control over the company (Rey-Garcia 2017).

With the characteristic geographical location, approximately one-third of publications (29%) cover the fact that the sphere of activity of a CF can be determined in its governing documents, that is, the description of the purpose for which the CF exists. It might be aligned with the most important sales market of the business or the location of the company’s headquarters. For instance, the results of the study by Morsy (2015: 1523) show that “corporate funders keep their grants close to headquarters, targeting their local education community.” However, only a handful of publications (4%) to date cover the aspect of shared geographical location in regard to the headquarters of a CF and its founder.

-

(2)

Organizational Capabilities

The second global theme, organizational capabilities, groups together three characteristics that authors have used to describe the resources and organization of CFs (see Fig. 6). Although these two are relevant to any charitable foundation, their configuration is different in CFs and may have consequences, e.g., for the self-image of the CF.

The majority of publications (63%) refer financial resources, which involve all forms of regular/one-time cash, such as donations or a share of product sales. In this context, fewer publications (43%) mention assets that were given to the CF in cash, company shares or real estate at the time of its establishment. Where authors discuss the type of donor of these financial resources (38%), in almost all cases they name the corporate or institutional founder. Approximately one-third of them name corporate employees, while a few even mention the customers of the corporate founder. Minciullo (2016: 212) points out that “the majority of the income comes from a corporate source, but through diverse channels, like investment income on assets originally given by a company, regular donations from a company, an endowment linked to a company’s profits, money raised by a company’s or employees’ fundraising efforts, and gifts and support in kind.”

Nonfinancial resources can take many different forms. Human resources (e.g., volunteers) are mentioned most frequently (60%), know-how (e.g., legal advice) is mentioned half as often (31%), and infrastructure (e.g., workplaces) is mentioned even less frequently (23%). Bethmann and Schnurbein (2015: 21) confirm that “In kind support is often given by providing office space or the ability to resort to company resources such as legal advice, human resources or support in financial management.” There is little coverage of product donations (5%) or the type of compensation (4%), which might be free of charge, at cost price or at market price.

The organization of CFs is covered in the scholarship by means of six aspects. Board composition receives the most attention (53%). In this regard, publications deal primarily with the institutional affiliation of board members (to the founder) and only marginally with the size and balance of competencies or genders on the board. For instance, Xu et al. (2018: 2) highlight the situation in China, where “nearly 90% of CFs’ board members come from the founder firms and 65% of them are top-level executives (CEOs, CFOs and COOs).” The second most frequently discussed issue is the recruitment process (30%), which is either an open call or recruitment via the company's personnel pool. The organizational structure (23%) is quite naturally divided into strategic decision-making and operational management parts, which are sometimes supported by additional advisory boards or committees staffed by external experts or decision makers from the founding body. Regarding regulation (23%), various influencing factors are mentioned, of which the most important seem to be hard law and the foundation's own policy. Soft laws relating to the foundation sector (e.g., recommendations of membership bodies for charitable foundations) or company policy (e.g., corporate governance codes) is not of great interest in either the academic or gray literature. Reporting (18%) is associated more with the company than with the public. To date, the remuneration of the board (8%) or management team is of marginal interest in scholarship.

-

(3)

Purpose

The third global theme, purpose, summarizes six characteristics that revolve around the foundation’s funding practices with which it fulfills its purpose (see Fig. 7). Some of them concern internal processes, the foundation’s decision on its form of operation, while others concern the foundation’s external funding ecosystem with which it interacts and communicates.

CF aims can be broken down into two main categories: (corporate) enhancement (38%) and (societal) support (34%). A CF serves more corporate goals if it executes a company’s CSR strategy, if it makes a positive contribution regarding corporate identity, culture or reputation, and if it legitimizes a company’s activities. For example, one author recognizes an “evolution from solely philanthropy to the strategic CSR of corporate foundations,” which results in CFs that “today do not operate with the limited mission of donating funds; rather they execute an overall CSR strategy in line with their parent companies’ strategies” (Altuntas and Turker 2015: 548). According to the analysis, a CF is more likely to target social support when it solves social problems, satisfies unmet social needs or promotes innovation. Of course, the two types of goals are not mutually exclusive, but authors tend to emphasize one type in particular. The difference between the two characteristics of intention and aim lies in their temporal order. On the one hand, intention indicates the original impulse of the founder for the creation of the CF. On the other hand, aim describes the purpose that the foundation wants to pursue through its activities. Intention and aim can but do not necessarily have to be the same.

As with any charitable foundation, the way in which the mission of the foundation is achieved, that is, its operations, is one important feature of description. However, only one-third of the sample publications address this fact, most of them with the perception that CFs achieve their purpose through grant-making activities (25%). Others, such as operational (6%), entrepreneurial investments (5%) or mixed approaches (3%) as well as operating own business (3%), are mentioned rarely but with similar frequency.

The characteristic self-concept summarizes the different roles attributed to CFs in the sample. Most frequently, authors refer to CFs as communicators (51%): as visual demonstrations that communicate the philanthropic commitment of the company to the outside world and as important communication channels that convey the values and culture of the company and translate social expectations back into it. When authors speak of CFs as converters (38%), they argue that CFs transform their available financial and nonfinancial resources into value for society and/or the company. Less often, the publications contain descriptions that identify CFs as connectors (26%) that facilitate cross-sector interaction, serve as a meeting place for the most diverse stakeholders and actively try to bridge the gap between the logics of different sectors. Only a few publications describe CFs as innovators (14%) or mobilizers (11%). The former see themselves as incubators for new business ideas or as a risk-taking mini-laboratory in the founding company’s area of activity while focusing on social innovation. Mobilizers, by contrast, appear in both society and their founding companies as advocates for specific social and environmental issues, and they often see themselves as critical voices. For example, this can take the form of “a kind of watchdog activity, in which institutes and foundations are given the role of monitoring and oversighting the socio-environmental performance of areas of the business” (Oliva 2017: 31).

The fourth characteristic summarizes statements on the communication of CFs, which can be grouped into three manifestations. Almost half of all the publications address aspects of organizational communication (43%) relating to the CF’s external image, including the CF’s logo and name, the public and media relations to inform the public about the CF. The aim of interactive/mutual communication (26%) by a CF is to address the relevant stakeholder groups in a differentiated and more personal way. CFs’ internal communication (14%) is addressed by approximately a quarter of the authors. They refer mainly to the company's employees, who obtain information about the CF via the corporate intranet or the employee magazine and show positive effects in terms of increased identification, trust and loyalty to the company.

The timing of a CF has not often been mentioned under this designation in scholarship. However, descriptions of CFs often contain temporal elements, such as the stability of funding activity in the face of economic fluctuations (33%) and the lifetime of the organizational form (26%), which refers to the long-term nature of CFs’ activities. Kramer et al. (2004: 2) see a major benefit in CFs in that “they permit the company to time-shift its contributions. This can serve to smooth fluctuations in earnings, capture a windfall, or announce a major contribution before knowing how it can best be spent.”

The institutional environment of CFs is a highly discussed feature that deals with, for example, influences from the business sector (46%), such as group pressure from philanthropically committed competitors, industry-specific approaches to corporate philanthropy and market dynamics. However, the findings by Peterson and Su (2017: 1191) suggest that “how corporations responded to the increased need for charitable contributions during an economic slowdown appears to depend on the type of industry” rather than fluctuations in the economy. The statements that are summarized under society (41%) mostly revolve around culture-specific values and expectations of social corporate commitment, the confrontation within the company or CF with critical stakeholders, activism and campaigns against or for certain topics, and challenges posed by social mass media. Influences on CFs from the NPO sector (24%) include the need for professionalization and the dynamics within subject areas such as climate change. The public sector (24%) influences CFs through changes in foundation or tax law and declining public investment.

-

(4)

Outcome

The fourth global theme, outcome, is result oriented and groups together two characteristics that authors have used to describe practices regarding impact measurement and certain challenges that are specific to CFs and may result from their more or less close relationship with their founding company (see Fig. 8).

Most authors discuss impact in relation to the corporate founder (69%), i.e., the many ways in which the CF brings an positive benefit to the company, particularly in terms of relationship management and reputation. The impact on society (31%) generally revolves around increasing prosperity, with the CF being a role model for philanthropic engagement and its ability to have a positive social impact. For example, a CF “may use the power of money to push the nonprofit sector toward greater transparency, efficiency, accountability, and justice” (Zhou 2015: 1159). The impact on other stakeholders (13%) or the CF itself (6%) is little discussed by authors.

The majority of authors see challenges in CFs regarding their governance (43%). Some authors also mention challenges regarding CFs’ reputation (38%) or operational activities (24%). The fact that economic (19%) or legal (6%) risks are hardly mentioned can be explained by the countries of origin of the data, which mostly have stable democratic and economic structures. Governance risks include statements on checks and balances, conflicts of interest and CFs’ independence from the founding body. Reputational risks relate to fears of being considered an instrumental tool of the company. Operational risks are associated with local or thematic alignment with the founding company, lack of knowledge on the board of trustees, loss of objectivity and lack of impact. Authors see economic challenges as arising from CFs’ dependence on a dominant donor—the founding company and legal challenges in the possible loss of nonprofit status or regulatory changes.

Hybridity

Research question two asked: Which configurations of characteristics are key for the patterns of hybridity in CFs? Table 1 provides an overview of the number of reviewed publications in which one or more of the three perceptions of hybridity were identified.

On a strategic level, a total of eight academic and six gray publications observe CFs as hybrid organizations due to their style, approach or target beneficiaries. On an organizational level, the majority of publications, 37 academic and 29 Gy publications, explain the “hybrid nature” of CFs due to their specific governance structure or resources. Referring to the contextual environment and sociopolitical setting of CFs, only 11 academic and two gray publications state hybridity in CFs. Compared to academic publications, practitioner-focused publications tend to relate hybridity somewhat more to aspects of the organizational level.

Furthermore, relating the four themes, 15 characteristics and 54 manifestations of the attribute space (Fig. 4) to the three levels of hybridity, the analysis found that some aspects are considered more relevant than others. Figure 9 shows in color gradation how many publications the respective manifestation was coded in relation to their understanding of hybridity; the greater the number of codings, the darker the color. A blank cell means that the descriptor was not found in any of the publications with this understanding of CF hybridity. Thus, not all 15 characteristics and their 54 manifestations are equally meaningful in regard to the question of which key aspects lead to patterns of hybridity in CFs.

Several characteristics are most commonly addressed in all three perceptions or levels of hybridity: the founding body (in particular, the corporate body), the intention to establish a CF (to benefit both society and the corporate founder), financial resources (especially regular/one-time cash), nonfinancial resources (in particular, human resources) and the impact of foundation activities (in particular, on the corporate founder). Both the hybridity of intentions and the hybridity of resources are not surprising, as these were most often associated in the extant literature with the hybrid nature of CFs.

At the same time, several characteristics are considered to be of relatively low or zero relevance, as they are least associated with the levels of hybridity. These are geographical location (in particular, the workplace of the CF), nonfinancial resources (especially the form of compensation for the founding company for these kinds of resources), organization (in particular, the remuneration of board members and the reporting requirements to different stakeholders), operations (in particular, all forms of activity other than grant-making), communication (internal) and challenges (especially legal risks).

A note of caution is necessary here. The fact that some manifestations occur with similar frequency in different hybridity levels indicates the complexities inherent to CFs, which makes a clear delineation of the patterns of hybridity based on the characteristics infeasible. Instead of being static and sharp, the boundaries of the three levels overlap at some point as CFs’ hybridity levels blend into each other and may change. At the same time, the frequency of the codings reflects, as is usually the case in quantitative literature reviews, a retrospective conception of what is perceived to lead to hybridity in CFs. The least mentioned manifestations should not necessarily be regarded as insignificant for hybridity patterns; rather, they should be regarded as starting points for future research and as requiring further examination. Nevertheless, a clear tendency for certain groups of characteristics to be associated with one of the three hybridity levels can be observed.

Discussion and Directions for Future Research

This study reviews a comprehensive range of academic and practitioner-oriented publications on CFs from 1970 to 2018. To date, the literature on CFs has uncovered and described a rich and complex variety of different CF types in over 30 countries worldwide. The primary purpose of the review was to synthesize these conceptualizations beyond their country-specific relevance to create a baseline understanding of the set of characteristics that have been used to describe CFs and to provide a more nuanced understanding of which of these lead to patterns of hybridity in CFs on strategic, organizational and contextual levels. The following section discusses the findings and develops three propositions to guide future research.

Characteristics

The financial dependency of CFs on their founding companies is widely used in definitions of CFs as one of the key features that distinguishes them from other classic charitable foundations and to describe their hybrid nature between business and society. However, the findings of this review show that future researchers may use a comprehensive set of 15 characteristics along four themes to better understand and describe the complexity of CF types. Future conceptualizations should at least include characteristics from each of the four themes, i.e., establishment, organizational capabilities, purpose and outcome. Doing so would help to overcome the particularism of CF definitions beyond their country-specific political, legal and social contexts. Moreover, it would allow us to relate the inherent tensions between independence and control not only to financial aspects but also to other aspects where they may also be apparent, e.g., the intention of establishing a CF. At the level of the individual foundation, the attribute space helps in determining what belongs to the CF phenomenon and what does not. Foundations in general are heterogeneous, just like CFs differ in size, governance and purpose. From the outside, it is often difficult to assess whether a foundation possesses the characteristics that are typical for CFs. Belonging to this group can be a decisive advantage for foundation managers, as CFs are known to actively exchange knowledge and expertise with fellow CFs on international and national level.

From the main findings of the literature review, the following operational definition is proposed to inform further empirical research: CFs are formally nonprofit and not commercially oriented organizational structures, and although not every foundation has a charitable status, CFs are set up, funded and supported with various organizational capabilities by one or several corporate-related founding bodies with the aim of creating an impact on society and their founder. While being hybrid organizations on a strategic, organizational or contextual level, CFs manage the expectations and challenges of the multiple environments to which they are formally linked and in which they operate.

Hybridity

The second research question of this review explored the key characteristics that lead to patterns of hybridity in CFs. The findings change the present understanding of hybridity in CFs from being uniform for all CF types to being multidimensional on different levels.

-

(1)

Strategic hybridity

The characteristics most associated with strategic hybridity belong to the themes establishment, purpose and outcome. A decisive component for hybridity at the time of establishment is, when the intention of the corporate founder for the CF is both societal and corporate driven. Within the third theme, purpose, the self-concept of a CF, especially when it is a connector, a communicator, an innovator or a mobilizer, has the potential to lead to hybridity on this level. For instance, Herlin and Pedersen (2013: 58) find that “corporate foundations have the potential to act as boundary organizations and facilitate collaborative action between businesses and NGOs through convening, translation, collaboration and mediation.” This stands in contrast to the contextual and organizational hybridity levels, where the roles of innovators and mobilizers are rarely associated. Hybridity on a strategic level seems to require more than the transformation of financial resources into impact; rather, it requires a strategic awareness of the role that the foundation plays between society and business in fulfilling its purpose. Also relevant, although somewhat less so, is the aim of the funding activities, in particular when directed toward societal support and corporate enhancement. Communication, especially in an interactive/mutual way, supports hybridity on this level. In addition, the institutional environment, when the business sector and society are equally considered in the foundation’s funding practices, is likely to influence the foundation’s degree of hybridity on a strategic level. Such CFs “engage with delivery partners, communities, governments and others to advocate for change and create impactful solutions to global problems” (Corporate Citizenship 2016: 7). For hybridity to manifest itself on a strategic level, it also seems relevant that the impact of the foundation’s funding practices is directed at both the corporate founder and society.

Proposition 1

CFs are strategically hybrid when they intentionally act as bridge builders that mobilize and blend societal and market forces to create participatory and innovative solutions for the welfare of society and their corporate founder.

-

(2)

Organizational hybridity

The characteristics most associated with organizational hybridity belong to the themes establishment and organizational capabilities. Some features of the theme purpose are also linked with organizational hybridity, to the extent that they concern the intraorganizational practices of CFs. Unlike the other two levels, hybridity at this level is primarily associated with issues related to the organizational design of CFs, which were either determined by the founder at the time of establishment or which lie mostly within the direct control of the foundation’s current management. More specifically, within the first theme, the characteristics most discussed are the founding body itself, the founder’s intention and legal issues. For such CFs, the corporate founding body seems to be the decisive parameter that significantly influences the intensity of organizational hybridity. For example, the intention is somewhat more guided by possible corporate benefits than by social benefits, just as, later, the impact on the corporate founder is more relevant than the impact on the other stakeholders of the CF. While for such CFs the founder comes into play with regard to several issues, their charitable character and autonomy (legal independence) are particularly emphasized as the other side of the coin. In contrast to contextual hybridity, both the nature and availability of financial resources and their sources as well as nonfinancial resources, especially the know-how and human resources of the corporate founder, play a central role. In contrast to the strategic level, questions of governance, in particular concerning board composition with external and corporate members and their recruitment process, are more often linked to the organizational level. The self-concept ranges from that of a converter, who channels the company’s financial resources to a good cause, to that of a communicator, who communicates about the goals and activities of the foundation as a visible manifestation of the philanthropic commitment of its founder. Directly related to this is a communication practice that is focused on the external perception of the foundation, i.e., the foundation’s corporate identity, PR/events or online communication, directed toward both the business sector and society. The challenges for CFs are discussed mainly in the area of reputation and governance risks, given the interdependencies with their founding body on several levels. The following is therefore concluded:

Proposition 2

CFs are organizationally hybrid, when their alignment with their corporate founder and their roots in the nonprofit sector are reflected in their organizational design to achieve their social purpose with the most efficient structures and processes while being accountable to their founding body.

-

(3)

Contextual hybridity

Publications that assign hybridity in CFs to the contextual level primarily refer to the characteristics of the themes establishment and outcome. Within the themes organizational capabilities and purpose, only selected characteristics are linked to this level. In general, these are features that concern the sociopolitical setting of CFs and that tend to be rather outside their direct sphere of influence. Within establishment, the founding body, intention and legal characteristics are the characteristics mentioned most often. A corporate founder is mentioned primarily as a founding body, while social and corporate benefits are given equal consideration in descriptions of the founder’s intention. Both components of the legal characteristic, the foundation type and autonomy, are relevant for contextual hybridity in a similar way, as they reflect in this case the links and roots of CFs to the nonprofit sector. For example, Wang et al. (2017: 1) state, “family business firms may fund philanthropic foundations with an intention of financial contribution connecting to the society.” By signaling their social commitment, they intend to “obtain financial benefit over time” and generally expect to be rewarded by their community. Within the fourth theme, authors discuss challenges in the context of contextual hybridity more often than with the other two levels. The balancing act between the sector of origin and resources, the business sector, the sector of primary affiliation, the nonprofit sector, and the sector to which the funding activities are directed, society, seems to be accompanied by more risks, more regulatory issues regarding the foundation’s organization, a need for greater sensitivity to the compatibility of the intentions and aims of the foundation and a greater need for outward communication with the institutional environment. The latter characteristics are most often associated with this level, as the potential impact of the environment on the foundation’s approach to fulfilling its purpose might be particularly high. For example, by analyzing the “effects of tax and other government policies on the establishment and use of corporate foundations,” Webb (1994: 62) finds that “tax and government policy makers can affect the timing and amount of corporate charitable donations by changing the corporate marginal tax rate, the social perceptions of corporate charitable activities, the rulings on tax liability for foundations, and laws on deductibility of corporate gifts.”

Proposition 3

CFs are contextually hybrid, when they address the various influences and pressures they face from the multiple environments in which they operate in their organizational structures and activities in a way that balances these expectations in the best interest of the foundations’ charitable purpose.

Based on the analysis, these three propositions provide a baseline understanding of the configurations of characteristics that were found to lead to different patterns of hybridity in CFs. Several gaps and open questions remain for future research to acquire an even more comprehensive conceptualization of what constitutes hybridity. First, further exploration is needed with regard to the interlinkages between the strategic, organizational and contextual levels. Although most publications relate the hybrid nature of CFs primarily to one of the three levels, there are some where this is less obvious. In fact, five out of 80 publications consider hybridity to be identifiable at the strategic and organizational levels, another five at the organizational and contextual levels, and another three at the strategic and contextual levels, although to varying degrees. This overlap indicates that hybridity in CFs may not be a static condition but, rather, be subject to transformation as foundations change and adapt (Battilana and Lee 2014). What triggers these dynamics and how the transition takes place within a foundation would be interesting for researchers to further explore.

Second, scholars interested in typologies might examine whether clusters of similar CFs can be formed based on their degree of hybridity. Little is known about how best practices in governance, communication or funding change between such clusters. Future research might use cluster analysis to find those specific clusters and to investigate whether there is a “level-specific” way of coping best with hybridity.

Third, this review supports a rather positive connotation of the hybrid nature of CFs. Other researchers, such as Brandsen et al. (2005), argue that hybridity should be regarded as an inherently positive trait that provides unique opportunities for the parties involved. However, the hybrid nature of CFs is often considered a complicating or even frustrating feature that poses particular challenges to practitioners in the field. Therefore, a more nuanced discussion of whether CF hybridity entails both an opportunity and a risk for CFs and their internal and external stakeholders, such as their target beneficiaries, is needed. In the context of social enterprises, this dual effect of hybridity and its challenging influence on the mission and the mobilization of financial and human resources is well known (e.g., Battilana and Lee 2014; Doherty et al. 2014). The following question arises: To what extent do CFs face similar implications and what strategies should they use to respond to these challenges based on their level of hybridity? For example, in terms of risks, it is well known that external stakeholders sometimes have rather negative perceptions of CF hybridity and that these perceptions are the source of mistrust in the legitimacy and performance of foundations (Marquardt 2001). It would be useful to differentiate whether different levels of hybridity result in a positive, negative or neutral reputation for the CF and whether this is mirrored back to their founding company. Regarding opportunities, one might think of the possible role of CFs with regard to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, which demand collaboration between diverse actors holding different institutional logics. CFs in the role of partnership brokers may be particularly qualified to initiate multistakeholder partnerships between actors from the private sector and civil society due to their unique links to and roots in both sides (Gehringer 2020).

Fourth, this study concentrated on discussing the emergence of hybridity on particular levels due to distinctive configurations of characteristics. Further research is required to explore the consequences that hybridity on these levels may have for the performance and effectiveness of CFs. With regard to governance, previous research has shown that the implementation of coordination and bureaucratic control mechanisms between a CF and its founder firm strengthens the board’s involvement and leads to higher organizational effectiveness in CFs (Minciullo and Pedrini 2020). Scholars could examine in more detail how and when different degrees and levels of hybridity help to achieve higher organizational effectiveness and increase the envisioned impact on society.

Concluding Remarks

This literature review comes at a time when scholars from the nonprofit literature show increasing interest in CFs as an institutionalized form of corporate philanthropy (Roza et al. 2020). Of particular interest in the literature to date are the challenges for governance, funding practices or identity as a result of the divergent characteristics, such as a socially driven vs. corporate-driven intention, that CFs combine at their core. Often, these internal and external tensions of organizational features have resulted in the label “hybridity,” which is often attached (e.g., Herlin and Pedersen 2013; Minciullo 2016; Sloane et al. 2003), though without a finer-grained understanding of what exactly constitutes this hybrid nature of CFs (Skelcher and Smith 2015).

At the same time, scholars with roots in organizational theory have paid increasing attention to types of hybrid organizations other than social enterprises. Over the last three decades, these have developed into well-studied objects that are considered to be ideal settings where hybridization occurs (Battilana and Lee 2014; Wolf and Mair 2019). Recently, organizational scholars have started to show interest in how alternative forms such as CFs combine and make sense of for-profit and nonprofit elements.

Within this context, this review synthesizes the existing knowledge of CFs from both the academic and gray literature to provide a comprehensive attribute space of characteristics and to offer a clearer understanding of which configurations of characteristics are key for patterns of hybridity. In combining the theoretical lens of hybridity and a four-step methodological approach, the literature review allows a step toward gaining a detailed understanding of the causal relationships between CF characteristics and hybridity. Based on the findings of the review, the study discusses how future research may contribute to the study of charitable CFs and will hopefully expand knowledge on their hybrid organizational form.

The findings from this research are the result of a literature-based thematic content analysis that is subject to certain limitations. First, the review is bound by the geographical focus of the selected academic and gray publications. Future research may identify changes or supplements to the findings by considering sources published in languages other than English and German. In particular, this could lead to a higher coverage of studies from Africa, Latin America and Australia/Oceania and, thus, a better balance of the sample, as a bias toward studies from the USA, the UK and Germany was noted. Second, the selection of sources was determined by a specific time frame. While the available literature on CFs, especially of a conceptual nature, is scarce (Rey-Garcia et al. 2018), the review manages to cover a comprehensive set of 80 publications. However, more recent sources published after the closing date of December 31, 2018, are missing (e.g., Monfort et al. 2021; Roza et al. 2020). This is a gap that future studies may aim to address by expanding the sample beyond its current scope. Third, the review focused on explaining how key characteristics of CFs interact and lead to patterns of hybridity. The focus of the study on the three levels of hybridity is arguably quite broad, and their degree of overlap is not yet clear. Nevertheless, this literature review is relatively comprehensive in that it brings together sources from the academic and gray literature from over 30 countries worldwide. It goes beyond other systematic reviews of the literature in the field, such as that by Gautier and Pache (2015) on corporate philanthropy or that by Feliu and Botero (2016) on philanthropy in family enterprises, by offering a holistic analysis of CF characteristics and their relevance for hybridity. Future research may verify and further develop the current propositions of this paper. For example, scholars may explore how CFs deal with the consequences of hybridity and whether there are particular differences in their way of doing so based on foundation sector-specific traditions. Additionally, it would be interesting to examine whether a CF changes its level of hybridity over time and how these dynamics affect the identity and funding practices of foundations.

The findings of this study contribute to a better understanding of the existing heterogeneity of the CF phenomenon, in particular their hybrid organizational nature, and they allow a more informed discourse among practitioners and academics in the field of corporate philanthropy and organizational theory.

Notes

The Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research (ANSERJ), the International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, the International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law (IJNL), the International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, The Nonprofit Review, the Journal of Civil Society, The Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity (JEOD), the Journal of Governmental & Nonprofit Accounting (JOGNA), the Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly (NVSQ), Nonprofit Management & Leadership (NML), the Nonprofit Policy Forum (NPF), The China Nonprofit Review, the International Journal of Community Service Learning (IJCSL), the Third Sector Review, the Voluntary Sector Review, and VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations.

SpringerLink, Emerald, ScienceDirect, Business Source Premier, JSTOR, Wiley, SAGE Publications and Google Scholar.

References

Altuntas, C., & Turker, D. (2015). Local or global: Analyzing the internationalization of social responsibility of corporate foundations. International Marketing Review, 32(5), 540–575.

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405.

Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing: Insights from the study of social enterprises. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397–441.

Bethmann, S., & von Schnurbein, G. (2015). Effective Governance of Corporate Foundations, CEPS Working Paper Series (No. 8), Center for Philanthropy Studies (CEPS), Basel.

Billis, D. (2010). Hybrid organizations and the third sector: Challenges for practice, theory, and policy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brandsen, T., van de Donk, W., & Putters, K. (2005). Griffins or chameleons? Hybridity as a permanent and inevitable characteristic of the third sector. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(9–10), 749–765.

Bothello, J., Gautier, A., & Pache, A.-C. (2020). Families, firms, and philanthropy: Shareholder foundation responses to competing goals. In L. Roza, S. Bethmann, L. Meijs, & G. von Schnurbein (Eds.), Handbook on corporate foundations. Nonprofit and civil society studies (an international multidisciplinary series) (pp. 63–82). Cham: Springer.

Candid. (2020). Key facts on U.S. Nonprofits and foundations. New York.

Corporate Citizenship (CC). (2014). Corporate foundations. A global perspective, London.

Corporate Citizenship (CC). (2016). The game changers. Corporate Foundations in a Changing World, London.

Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 417–436.

Ernst & Young Société d’Avocats and Les entreprises pour la Cité. (2014). Panorama Des Fondations Et Fonds De Dotation Créés Par Des Entreprises, Paris.

European Foundation Centre. (2003). Typology of foundations in Europe. Brussels.

Feliu, N., & Botero, I. C. (2016). Philanthropy in family enterprises: A review of literature. Family Business Review, 29(1), 121–141.

Fiss, P. C. (2011). Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 393–420.

Gautier, A., & Pache, A.-C. (2015). Research on corporate philanthropy: A review and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 126, 1–27.

Gehringer, T. (2018). Corporate Foundations in der Schweiz. Bilanz und Neuentwicklung. Stiftung&Sponsoring (pp. 16–17).

Gehringer, T. (2020). Corporate foundations as partnership brokers in supporting the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs). Sustainability, 12, 7820.

Gehringer, T., & von Schnurbein, G. (2020). Corporate foundations in Europe. In L. Roza, S. Bethmann, L. Meijs, & G. von Schnurbein (Eds.), Handbook on corporate foundations. Nonprofit and civil society studies (an international multidisciplinary series) (pp. 85–106). Cham: Springer.

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108.

GreyNet [Grey Literature Network Service]. (2018). GreyNet International 2018. http://www.greynet.org/. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

He, L., & Wang, Q. (2020). Do Chinese corporate foundations enhance civil society? In L. Roza, S. Bethmann, L. Meijs, & G. von Schnurbein (Eds.), Handbook on corporate foundations. Nonprofit and civil society studies (an international multidisciplinary series) (pp. 125–47). Cham: Springer.

Herlin, H., & Pedersen, J. T. (2013). Corporate foundations. Catalysts of NGO–business partnerships? Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 50(50), 58–90.

Hirsch, A., Neujeffski, M., & Plehwe, D. (2016). Unternehmensnahe Stiftungen im Spannungsfeld zwischen Gemeinwohl und Partikularinteressen. Eine Exploration im Bereich Wissenschaft. Discussion Paper SP I 2016–201r, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, Berlin.

Jäger, U. P., & Schröer, A. (2014). Integrated organizational identity: A definition of hybrid organizations and a research agenda. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25(5), 1281–1306.

Jung, T., Harrow, J., & Leat, D. (2018). Mapping philanthropic foundations’ characteristics: Towards an international integrative framework of foundation types. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(5), 893–917.

Kramer, M., Pfitzer, M., & Peterson, K. (2004). Perspectives on corporate philanthropy corporate giving and the corporate foundation. Boston: FSG Foundation Strategy Group.

Kuckartz, U. (2010). Einführung in die computergestützte Analyse qualitativer Daten (3rd ed., Vol. 91). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Maas, S. A. (2020). Outsourcing of corporate giving: what corporations can(’t) gain when using a collective corporate foundation to shape corporate philanthropy. In L. Roza, S. Bethmann, L. Meijs, & G. von Schnurbein (Eds.), Handbook on corporate foundations. Nonprofit and civil society studies (an international multidisciplinary series) (pp. 193–215). Cham: Springer.

Marquardt, J. (2001). Corporate foundation als PR-Instrument. Gabler, Wiesbaden: Rahmenbedingungen - Erfolgswirkungen - Management.

Minciullo, M. (2016). Fostering orientation to performance in nonprofit organizations through control and coordination: The case of corporate foundations and founder firms. Governance and Performance in Public and Non-Profit Organizations, 5, 207–232.

Minciullo, M., & Pedrini, M. (2020). Antecedents of board involvement and its consequences on organisational effectiveness in non-profit organisations: A study on European corporate foundations. Journal of Management and Governance, 24, 531–555.

Minefee, I., Neuman, E. J., Isserman, N., & Leblebici, H. (2015). Corporate foundations and their governance: Unexplored territory in the corporate social responsibility agenda. Annals in Social Responsibility, 1(1), 57–75.

Monfort, A., Villagra, N., & Sánchez, J. (2021). Economic impact of corporate foundations: An event analysis approach. Journal of Business Research, 122, 159–170.

Morsy, L. (2015). Corporate philanthropic giving practices in U.S. school education. Voluntas, 26(4), 1510–1528.

Oliva, R. (2017). Alignment between private social investment and business. São Paulo: GIFE.

Pache, A.-C., & Santos, F. (2013). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. The Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 972–1001.

Pedrini, M., & Minciullo, M. (2011). Italian corporate foundations and the challenge of multiple stakeholder interests. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 22(2), 173–1197.

Peterson, D. K., & Su, Y. (2017). Relationship between corporate foundation giving and the economic cycle for consumer- and industrial-oriented firms. Business & Society, 56(8), 1169–1194.

Prophil. (2015). Shareholder foundations. Paris: The First European Study.

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Elam, G., Tennant, R., & Rahim, N. (2014). Designing and selecting samples. In J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, C. McNaughton Nicholls, & R. Ormsten (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp. 111–146). London: Sage Publications.

Rey-Garcia, M. (2012). Beyond corporate social responsibility: Foundations and global retailers, DOCFRADIS (No. 6), Oviedo.

Rey-Garcia, M. (2017). Understanding the governance of controlling foundations and foundation owned businesses (FoB). Copenhagen: The Case of Spain.

Rey-Garcia, M., Sanzo-Perez, M. J., & Álvarez-González, L. I. (2018). To found or to fund? Comparing the performance of corporate and noncorporate foundations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(3), 514–536.

Rey-Garcia, M., Layton, M. D., & Martin-Cavanna, J. (2020). Corporate foundations in Latin America. In L. Roza, S. Bethmann, L. Meijs, & G. von Schnurbein (Eds.), Handbook on corporate foundations. Nonprofit and civil society studies (an international multidisciplinary series) (pp. 167–190). Cham: Springer.

Roza, L., Bethmann, S., Meijs, L., & von Schnurbein, G. (2020). Introduction. In L. Roza, S. Bethmann, L. Meijs, & G. von Schnurbein (Eds.), Handbook on corporate foundations. Nonprofit and civil society studies (an international multidisciplinary series) (pp. 1–3). Cham: Springer.

Schreier, M. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 170–183). London: Sage Publications.

Skelcher, C., & Smith, S. R. (2015). Theorizing hybridity: Institutional logics, complex organizations, and actor identities: The case of nonprofits. Public Administration, 93(2), 433–448.

Sloane, N., Varcoe, L., & Rehm, E. (2003). Corporate foundations: Building a sustainable foundation for corporate giving. London: Business in the Community.

Smith, S. R. (2014). Hybridity and nonprofit organizations: The research agenda. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(11), 1494–1508.

Smith, S. R. (2016). Hybridity and philanthropy: Implications for policy and practice. In T. Jung, S. D. Phillips, & J. Harrow (Eds.), The Routledge companion to philanthropy (pp. 322–333). New York: Routledge.

Sprecher, T., Egger, P., & von Schnurbein, G. (2016). Swiss foundation code 2015 (foundation). Basel: Helbing Lichtenhahn Verlag.

Thomsen, S. (2012). What do we know (and not know) about industrial foundations? Copenhagen: Center for Corporate Governance.

Tremblay-Boire, J. (2020). Corporate foundations in the United States. In L. Roza, S. Bethmann, L. Meijs, & G. von Schnurbein (Eds.), Handbook on corporate foundations. Nonprofit and civil society studies (an international multidisciplinary series) (pp. 107–123). Cham: Springer.

Walker, E. T. (2013). Signaling responsibility, deflecting controversy: Strategic and institutional influences on the charitable giving of corporate foundations in the Health sector. Research in Political Sociology, 21, 181–214.

Wang, L.-H., Lin, C.-H., Kao, E. H., & Fung, H.-G. (2017). Good deeds earn chits? Evidence from philanthropic family controlled firms. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 49(3), 765–783.

Webb, N. J. (1994). Tax and government policy implications for corporate foundation giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 23(1), 41–67.

Wolf, M., & Mair, J. (2019). Purpose, commitment and coordination around small wins: A proactive approach to governance in integrated hybrid organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(3), 535–548.

Xu, L., Zhang, S., Liu, N., & Chen, L. (2018). Corporate hypocrisy: Role of non-profit corporate foundations in earnings management of for-profit founder firms. Sustainability, 10(11), 3991.

Zhou, H. (2015). Corporate philanthropy in contemporary China: A case of rural compulsory education promotion. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, 1143–1163.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Universität Basel (Universitätsbibliothek Basel).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions