Abstract

A total of 9.36 kb nucleotides of the C-terminal one-third genome of the canine Coronavirus (CCV) 1-71 strain, including all the structural protein genes and some non-structural protein (nsp) genes were cloned and sequenced. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence alignment as well as phylogenetic analysis of all the structural ORFs with reference coronavirus strains showed that CCV 1-71 was highly related to Chinese CCV isolates. This indicates that these CCV stains may have the same ancestor. Two large deletions were found in ORF3 and led to an elongated nsp3a and a truncated nsp3b. A single “A” insertion in a 6A stretch resulted in the truncation of nsp7b. The great variation in nsp3b and nsp7b indicates that these proteins are not essential for the viral replication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Canine coronavirus (CCV) was first isolated from US military dogs during an epizootic of diarrhea disease in Germany in 1971 [1]. The virus, designated 1-71, induced signs of gastroenteritis in neonatal dogs. Subsequently, it was isolated from other epizootics of canine diarrhea and was shown to have a worldwide distribution by serological surveys [2]. Today, CCV is generally considered to be an important etiologic agent responsible for mild to severe enteritis in young pups [3].

CCV is an enveloped, single-stranded positive sense RNA virus. On the basis of antigenic and genetic relationships [4, 5], CCV is classified as group I coronavirus within the family Coronaviridae, along with feline coronaviruses (FCVs) types I and II, transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) of swine, porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV), porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) and human coronavirus 229E (HCV-229E). The genome of CCV, 27–32 kb in length, contains two large open reading frames (ORFs), 1a and 1b. Those cover the 5′ two-thirds of the genome and are known to encode two polyproteins participating in the viral replicase formation. Structural proteins S, E, M, and N encoded by ORFs 2, 4, 5, and 6, respectively, and a number of presumptive non-structural (nsp 3a, 3b, 3c, 7a, and 7b) proteins are located downstream of ORF1b [4].

Coronaviruses are known to undergo high-frequency homologous RNA recombination events in vitro [6–8] and accumulate point mutations (as well as small insertions and deletions) in coding and non-coding parts of the genome every round of replication. This results in the proliferation of new virus strains, serotypes and subtypes that may show significant genetic differences [9]. Since it was first identified in 1971, CCV has evolved and the characterization of some new mutants, such as Insavc-1, BGF, CB/05, and the divergent UWSMN-1, Elmo/02 strains, have been reported [10–14]. To date, two different CCV genotypes are known which have been designated CCV type I and type II on the basis of their genetic relationship to FCV type I and type II strains, respectively [14, 15]. CCV type I viruses, genetically more closely related to FCV type I viruses, have not been adapted to in vitro growth and differ from CCV type II viruses greatly.

Molecular analysis of the genomic RNA can help to elucidate some aspects of the phylogenetic relationship and the mechanisms involved in pathogenesis. TGEV, PRCV, and FCV have already been characterized in detail. CCV, however, is the least characterized virus in group I. In the last three decades very little attention has been paid to CCV, and only a limited number of sequences corresponding to the C-terminal third of the genome are presently available. CCV 1-71, the first isolated CCV, is being used in many laboratories as a reference strain, and its pathogenesis has already been studied by virologic, histologic, histochemical, and immunoflurescent techniques [16]. Information about its genome and its phylogenetic relationship with other group I coronaviruses is, however, still unavailable. Here, we report the molecular characterization of the 9.36 kb C-terminal genome of CCV 1-71 strain encoding all the structural proteins and some non-structural proteins excluding the polymerase gene for which only 360 nucleotides have been determined.

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

Canine fibroma (A72) cell (ATCC CRL-1542) and CCV 1-71 stain (ATCC VR-809) were kindly provided by Professor Bajer, Giessen University, Germany. CCV KM and DF strains were isolated from symptomatic dogs in southwest and northeast China. CCV HC2, HF3, HR strains were isolated from healthy dogs, healthy foxes and healthy raccoon dogs in North China, respectively. A72 cells were propagated in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. CCV 1-71 and the CCV isolates were seeded on confluent A72 cells maintained in MEM with 2% FCS and harvested after 90% of the cells showed CPE.

PCR amplification

Viral RNA was extracted from infected A72 cells using the Trizol (Invitrogen Corp.) isolation reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions.

cDNA containing the 3′-end of pol1b protein, the structural proteins (S, E, M, and N) and the presumptive non-structural proteins (ORF3, ORF7) were cloned in eight partially overlapping fragments (Fig. 1). Synthesis of cDNA was carried out in a total reaction volume of 20 μl with M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Promega Corp.), as prescribed by the manufacturer. PCRs were performed as follows: 5 μl cDNA (50 ng) was added to a 50 μl PCR mix containing 2 mM dNTPs, 10 pmol of each primer, and 2.5 units of ExTaqTM DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Corp.) in buffer 1× to a final concentration of 1.5 mM MgCl2. PCR conditions consisted of an initial activation step of 95°C for 5 min followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 45–60°C, depending on the primer pairs, for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The sequence and position of all the primers are shown in Table 1.

The DNA was further purified with Agarose Gel DNA Purification Kit (TaKaRa Corp.) and cloned into pMD18-T vector (TaKaRa Corp.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing and sequence analysis

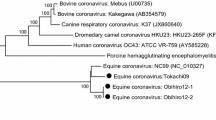

All clones were sequenced by Invitrogen Corp. The nucleotide sequence was determined in both directions on at least two separate amplicons for each fragment. Sequence data were edited and analyzed using EditSeq and MegAlign programs (DNAStar Konstanz, Germany) and aligned to other reference strains listed in Table 2. SignalP, TMHMM and NetNGlyc (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/) were used to predict signal peptides, transmembrane helices, and N-linked glycosylation sites. PROSITE database was used to identify different protein domains [17]. ORFs contained in the amplified genomic region were found either with the EditSeq or on the basis of the similarity to known coronavirus proteins. Phylogenetic analyses, based on the nucleotide and amino acid sequence of S, E, M, and N proteins were conducted with both Phylip 3.6 software package [18] and MEGA4 program [19] using Maximum parsimony (MP) and Neighbor-Joining (NJ) methods, respectively. Nodal support for the NJ and MP trees was evaluated by 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Genetic distances were estimated with the Kimura two-parameter model [20]. GenBank accession numbers of amplified genomic fragments and other reference strains used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Results

A total of 9.36 kb genomic sequence of the C-terminal of CCV 1-71, covering the 3′-end 360 bp of pol1b protein, all the structural proteins (S, E, M, and N) and some non-structural proteins (ORF3, ORF7), was successfully determined by amplifying and sequencing of eight adjacent fragments. However, the genomic sequences of stain CCV KM, HC2, HF3, and HR strains could not be amplified, with the exception of the N-terminal 1,470 bp of S genes (only for CCV-HF3 and CCV-DF) and M genes which were obtained through a nested-PCR method. These CCV strains, which were isolated from canidae animals in China, grow poorly on A72 cells with viral titers less than 103 TCID50/50 μl after more than 30 passages.

Alignment of the entire 9.36 kb of CCV 1-71 with TGEV, FCV, and other CCV genomes available in GenBank showed the highest pairwise sequence identity (94.3%) with CCV CB/05, a strain isolated from Italy and the lowest (73.5%) with CCV type I 23/03 strain. Comparison of the 3′ region of 1b gene (360 bp) to CCV Insavc-1, FIPV 79-1146 and TGEV-Purdue demonstrated high levels of sequence identity among group I coronavirus (94.5, 94.5, and 92.8%, respectively) but low levels of identity with MHV-A59 (53.5%) and IBV-p65 (55.3%).

The spike protein gene was 4,362 nucleotides long representing 1,453 amino acids, containing no insertions or deletions with respect to reference CCV strains GP, V1 and BGF10. Analysis with NetNGlyc, SignalP and TMHMM showed that it contained 31 highly conserved potential N-linked glycosylation sites, a putative signal peptide (cleavage sites at positions Cys 18 to Thr 19) and a transmembrane domain (positions 1,393 to 1,415 of S gene). This indicates that the spike protein is a type I membrane protein. The highest amino acids (aa) similarity of the spike protein was with CCV-GP (98.9%) and CCV-V1 (99.1%), two Chinese strains isolated from Giant Panda and dogs. A high level of nucleotide sequence identity (>94.2%) was demonstrated among CCV type II strains, whereas the identity to CCV type I strains was only about 53%. In accordance with previous observations, the sequence of the spike protein had a higher similarity with FCV type II (∼96%) than with FCV type I and TGEV strains (∼52 and 91%, respectively). The N-terminus of the protein was much more variable than the C-terminus. Analysis of the N-terminal 470 amino acids demonstrated that several residues, such as His-45, Ser-70, Asp-78, Thr-149, Ser-156, Ala-157, His-199, and Ser-394, were unique to CCV 1-71 and the four Chinese strains (GP, V1, HF3, and DF) isolated from different hosts (Giant Pandas, dogs and foxes) of different regions. The residue Leu-44 was present only in CCV 1-71 and TGEV strains. Phylogenetic analyses performed with nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the S protein revealed that CCV 1-71 was more closely related to Chinese strains than to other CCV reference strains (Fig. 2a).

Phylogenetic trees of CCV 1-71 and other reference strains based on nucleotide sequences of 5′ region of S gene (a), E gene (b), M gene (c) and N gene (d). Phylogenetic trees were constructed with MEGA4 program using Neighbor-Joining method as described in “Materials and Methods.” Bootstrap values are shown at the branch points. Bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions/site

ORF3 was located about 188 nucleotides downstream of the S gene, encoding three presumptive non-structural proteins. Alignment of this region with other CCV, FCV, and TGEV strains showed a high degree of variation. The nsp3a protein of CCV 1-71 was 87 amino acids long, 16-aa longer than that of all other strains due to the presence of a 47-nt deletion at position 206 of 3a gene and to a frame shift in the sequence downstream of the deletion. Another alteration caused by the deletion was the absence of the expected ORF3x designated initially by Horsburgh in 1992 [10]. An “ATTAC” sequence was found near the both sides of the deletion region. Another large deletion (31-nt) was found in the expected ORF3b of CCV 1-71, causing the introduction of an early stop codon and the formation of two truncated ORFs, designated 3b1 and 3b2 (411 and 357 nt, respectively, Fig. 3).

The envelope protein, like in all other group I coronaviruses, was found to be 249 nucleotides in length, coding for a polypeptide of 82 amino acids. A transmembrane domain was predicted between residue 15 and 37. Sequence analysis as well as phylogenetic studies (Fig. 2b) revealed the highest similarity of E protein gene with the Chinese isolate CCV-GP (98.4%).

The membrane protein (M protein) was 262 amino acids in length containing three transmembrane domains between residues 47 and 69, 76 and 98 and 113 and 135. A putative signal peptide (between positions Gly 16 and Glu 17) and three N-glycosylation sites were also predicted. The M protein of CCV 1-71 had high levels of amino acid sequence similarity (97.7–99.6%) with all the Chinese isolates, except CCV-NJ17 [21], with which it had a pairwise sequence identity of only 93.6%, indicating that for this gene region this is the most divergent Chinese strain. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed this relationship (Fig. 2c). The residue Ile at position 134 was found to be unique for CCV 1-71 and Chinese strains, with the exception of NJ17. Most of the mutations in the protein were accumulated within the N-terminal 50 amino acids.

The first nucleoprotein sequence (GenBank accession number AB105373, Sato et al., unpublished), 382 amino acids in length, was first characterized in 2003. In order to verify whether the protein has changed during the past 4 years, we sequenced the gene independently. Comparison showed that only one amino acid at position 212 mutated from Ser to Pro, which has no effect on the antigenicity. Five potential N-linked glycosylation sites could be found. The highest similarity (>99.2%) was obtained with Chinese strains mentioned earlier.

The nsp7a of CCV 1-71 had a length of 101 aa and a potential N-glycosylation site at position 30. A putative cleavage site between residues Leu-23 and Leu-24 and two transmembrane domains (positions 2–24 and 79–98) were also identified. In contrast to the intact nsp7a, nsp7b of CCV 1-71 was 118 aa long, 95 aa shorter than that of other CCVs, due to a single A insertion in a 6A stretch between nucleotides 341 and 346 of the gene. This insertion resulted in a frameshift mutation in ORF7b and a C-terminal truncated protein product (Fig. 4). Sequence comparison of the whole ORF7 revealed that nsp7b was much more divergent than nsp7a.

Discussion

CCV is generally recognized as a self-limiting pathogen of the small intestine, which can led to typical clinical signs of gastroenteritis. During the past three decades, attention was mostly paid to more virulent aetiological agents like canine adenovirus type 1, canine parvovirus type 2 or canine distemper virus (CDV) and less to CCV.

The emergence of several virulent CCV stains, i.e., BGF10 [11], CB/05 [12] and UWSMN-1 [13] confirmed that CCV alone could also cause systemic and fatal disease. CCV 1-71, the first isolated CCV, has already been identified as such a virulent strain [16]. However, comparative studies of these CCV strains were hampered as only few strains were proved to be suitable to grow in vitro. The lack of data from the last third of the genome containing the structural and non-structural proteins of CCV 1-71 and other different CCV isolates also prevented a powerful phylogenetic analysis. In the present study, a total of 9.36 kb nucleotides of the 3′ terminal of the CCV 1-71 genome were cloned and sequenced, with the aim to identify genomic regions involved in virulence and provide substantial genetic information of the virus for comparison with other coronaviruses.

Interestingly, CCV 1-71 was found to share the highest sequence identity and phylogenetic relationship with most Chinese isolates for the S, E, M, and N proteins, indicating that these strains may have the same ancestor. Several residues in the S protein, such as His-45, Ser-70, Asp-78, Thr-149, Ser-156, Ala-157, His-199, and Ser-394 that are unique for Chinese strains are also found in the S gene of CCV 1-71, which lends further support to this hypothesis. Despite the high sequence identity, two neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (Mab N1-2 and N2-1) specific to the S protein of CCV 1-71 cannot prevent infection of susceptive cells with these Chinese strains [25]. This indicates that notable diversity in the antigenicity of S proteins exists. Minor amino acid changes in the sequence of the spike protein have already been demonstrated to alter the virulence or enteric tropism of even very closely related TGEV isolates [26]. Single amino acid substitution in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein has also been confirmed to determine viral entry and immunogenicity of a major neutralizing domain [27]. Analysis of the N-terminal 500 amino acids of the S protein of CCV 1-71 and CCV HF3 demonstrated several amino acid substitutions, such as Leu-44, N-245, S-314, L-373. Whether these substitutions can be responsible for changes in antigenicity and virulence remains to be investigated by analysis of more sequences or by using reverse genetics systems similar to those recently used for FIPV [28].

Two large deletions of 47 and 31 nt were found in ORF3, resulting in a 16-aa longer 3a protein than expected, absence of the 3x protein and the truncation of 3b protein into two smaller ORFs. The existence of the truncated ORF3b also indicates that this ORF is not essential for the viral replication. Significant changes in the same region have also been reported in many other coronaviruses like CCV-CB/05 [12], TGEV-TF1, TGEV-Purdue, and PRCV-ISU-1 [29]. The non-coding regions upstream and downstream of ORF3a were considered to be a “hot spot region” where recombination, insertions or more usually deletions can occur at a high frequency [10]. Analysis of the deletion downstream of ORF3a in CCV1-71, CCV-CB/05 and TGEV-Purdue showed that an “ATTAC” sequence existed close to the both sides of the deletion region, suggesting that the deletion may be caused by a recombination event. It is also possible that these deletions arose from “looping out” of RNA regions, which may further result in the “skipping” of viral RNA polymerases during transcription. The search for the transcription regulatory sequences (TRS) in the region between S gene and ORF3a showed a “TTAAAC” site, different from the expected “CTAAAC”, which is highly conserved in group I coronaviruses. Both the nucleotide sequence of TRS and the distance between the TRS 3′-end and the initiation codon of first ORF are suggested to play an important role in the transcription of mRNAs [30]. The single nucleotide mutation in the TRS signal may reduce the transcription and expression of ORF3a. Unlike the intact nsp3b of the virulent CCV BGF10 strain, the nsp3b of CCV 1-71 is truncated in the middle of the sequence. Whether the two truncated ORFs (3b1 and 3b2) can be translated and whether the truncation is involved in changes of virulence need to be further studied. There are evidences in survey studies that the truncation of nsp3b is associated with attenuated strains [10, 31, 32]. Deletions in this ORF have also been suspected to play an important role in viral attenuation [33].

Another interesting mutation occurred in the sequence of ORF7b. A single “A” was inserted into a 6A stretch, resulting in the C-terminal truncation of the 7b protein (95 aa shorter than that of other CCV strains). This is the first report on the truncation of ORF7b in CCV. The same mutation via insertion was also found in the ORF3b gene of IBV strain Beaudette in which the ORF3b was truncated [34]. The region downstream of the N protein is another “hot spot region” where insertions and deletions can happen frequently [10]. TGEV, for example, has a 69 nucleotides deletion in ORF7a and ORF7b is not present. Although it has been confirmed, by a targeted RNA recombination system, that the 7b glycoprotein of FIPV is nonessential in vitro for virus viability [28], a connection between gene 7 and virulence has been observed in FCV as deletions in ORF 7a and ORF7b are associated with a decrease in virulence [35]. Similarly, the abrogated expression of ORF7 in TGEV does not affect virus propagation but attenuates the virus in piglets [36]. Whether the truncation of ORF7b could also lead to an attenuation of CCV1-71 should be further investigated.

In conclusion, sequence analyses in the present study stress the close relationship of CCV1-71 and the Chinese CCV strains. The 3′ one-third genome sequence of CCV1-71, especially the non-structural proteins, has undergone considerable variation during virus evolution. Further cloning and sequence analysis of genomic sequences of more CCV isolates as well as reverse genetics systems are required to reveal a clearer picture of the relationship between virus genome and pathogenicity.

References

L.N. Binn, E.C. Lazar, K.P. Keenan, D.L. Huxsoll, R.H. Marchwicki, A.J. Strano, Proc. Annu. Meet US Anim. Health Assoc. 78, 359–366 (1974)

B.J. Tennant, R.M. Gaskell, R.C. Jones, C.J. Gaskell, Vet. Rec. 132, 7–11 (1993)

Annamaria Pratelli, Vet. Res. 37, 191–200 (2006)

L. Enjuanes, W. Spaan, E. Snijder, D. Cavanagh, in Virus Taxonomy: Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, ed. by M.H.V. Regenmortel, C.M. Fauquet, D.H.L. Bishop, E.B. Carstens, M.K. Estes, S.M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M.A. Mayo, D.J. McGeoch, C.R. Pringle, R.B. Wickner (Academic Press, New York, 2000) pp. 827–834

C.M. Sanchez, G. Jimenez, M.D. Laviada, I. Correa, C. Sune, M. Bullido, F. Gebauer, C. Smerdou, P. Callebaut, J.M. Escribano, L. Enjuanes, Virology 174, 410–417 (1990)

M.M.C. Lai, R.S. Baric, S. Makino, J.G. Keck, J. Egbert, J.L. Leibowitz, S.A. Stohlman, J. Virol. 56, 449–456 (1985)

C.M. Sanchez, A. Izeta, J.M. Sanchez-Morgado, S. Alonso, I. Sola, M. Balasch, J. Plana-Duran, L. Enjuanes, J. Virol. 73, 7607–7618 (1999)

L. Kuo, G.J. Godeke, M.J. Raamsman, P.S. Masters, P.J. Rottier, J. Virol. 74, 1393–1406 (2000)

V.V. Dolja, J.C. Carrington, Virology 3, 315–326 (1992)

B.C. Horsburgh, I. Brierley, T.D.K. Brown, J. Gen. Virol. 73, 2849–2862 (1992)

J.M. Sanchez-Morgado, S. Poynter, T.H. Morris, Virus Res. 104, 27–31 (2004)

N. Decaro, V. Martella, G. Elia, M. Campolo, C. Desario, F. Cirone, M. Tempesta, C. Buonavoglia, Virus Res. 125, 54–60 (2007)

M.J. Naylor, C.S. Walia, S. McOrist, P.R. Lehrbach, E.M. Deane, G.A. Harrison, J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 3518–3522 (2002)

A. Pratelli, V. Martella, M. Pistello, G. Elia, N. Decaro, D. Buonavoglia, M. Camero, M. Tempesta, C. Buonavoglia, J. Virol. Methods 107, 213–222 (2003)

A. Pratelli, V. Martella, N. Decaro, A. Tinelli, M. Camero, F. Cirone, G. Elia, A. Cavalli, M. Corrente, G. Greco, D. Buonavoglia, M. Gentile, M. Tem Pesta, C. Buonavoglia, J. Virol. Methods 110, 9–17 (2003)

K.P. Keenan, H.R. Jervis, R.H. Marchwicki, LN. Binn, Am. J. Vet. Res. 37, 247–256 (1976)

L. Falquet, M. Pagni, P. Bucher, N. Hulo, C.J. Sigrist, K. Hofmann, A. Bairoch, Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 235–238 (2002)

J. Felsenstein, Cladistics 5, 164–166 (1989)

S. Kumar, K. Tamura, I.B. Jakobsen, M. Nei, Bioinformatics 17, 1244–1245 (2001)

M. Kimura, J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–120 (1980)

Y.Y. Wang, G.G. Ma, C.P. Lu, H Wen, Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 119, 35–39 (2006)

J.G. Wesseling, H. Vennema, G.J. Godeke, M.C. Horzinek, P.J. Rottier, J. Gen. Virol. 75, 1789–1794 (1994)

K. Motokawa, T. Hohdatsu, H. Hashimoto, H. Koyama, Microbiol. Immunol. 40, 425–433 (1996)

F. Almazan, J.M. Gonzalez, Z. Penzes, A. Izeta, E. Calvo, J. Plana-Duran, L. Enjuanes, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5516–5521 (2000)

G.G. Ma, Personal thesis of Master Degree

M.L. Ballesteros, C.M. Sanchez, L. Enjuanes, Virology 227, 378–388 (1997)

C.E. Yi, L. Ba, L. Zhang, D.D. Ho, Z. Chen, J. Virol. 79, 11638–11646 (2005)

B.J. Haijema, H. Volders, P.J.M. Rottier, J. Virol. 77, 4528–4538 (2003)

A. McGoldrick, J.P. Lowings, D.J. Paton, Arch. Virol. 144, 763–770 (1999)

T.L. Lin, C.C. Loa, C.C. Wu, Virus Res. 106, 61–70 (2004)

L. Kim, J. Hayes, P. Lewis, A.V. Parwani, K.O. Chang, L.J. Saif, Arch. Virol. 145, 1133–1147 (2000)

R.D. Wesley, R.D. Woods, A.K. Cheung, J. Virol. 64, 4761–4766 (1990)

P.S. Paul, E.M. Vaughn, P.G. Halbur, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 412, 317–321 (1997)

S. Shen, Z.L. Wen, D.X. Liu, Virology 311, 16–27 (2003)

A.A. Herrewegh, H. Vennema, M.C. Horzinek, P.J. Rottier, R.J. de Groot, Virology 212, 622–631 (1995)

J. Ortego, I. Sola, F. Almazan, J.E. Ceriani, C. Riquelme, M. Balasch, J. Plana, L. Enjuanes, Virology 308, 13–22 (2003)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, G., Wang, Y. & Lu, C. Molecular characterization of the 9.36 kb C-terminal region of canine coronavirus 1-71 strain. Virus Genes 36, 491–497 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-008-0214-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-008-0214-4