Abstract

Scientific studies are frequently used to support policy decisions related to transgenic crops. Schmidt et al., Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 56:221–228 (2009) recently reported that Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb were toxic to larvae of Adalia bipunctata in direct feeding studies. This study was quoted, among others, to justify the ban of Bt maize (MON 810) in Germany. The study has subsequently been criticized because of methodological shortcomings that make it questionable whether the observed effects were due to direct toxicity of the two Cry proteins. We therefore conducted tritrophic studies assessing whether an effect of the two proteins on A. bipunctata could be detected under more realistic routes of exposure. Spider mites that had fed on Bt maize (events MON810 and MON88017) were used as carriers to expose young A. bipunctata larvae to high doses of biologically active Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1. Ingestion of the two Cry proteins by A. bipunctata did not affect larval mortality, weight, or development time. These results were confirmed in a subsequent experiment in which A. bipunctata were directly fed with a sucrose solution containing dissolved purified proteins at concentrations approximately 10 times higher than measured in Bt maize-fed spider mites. Hence, our study does not provide any evidence that larvae of A. bipunctata are sensitive to Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 or that Bt maize expressing these proteins would adversely affect this predator. The results suggest that the apparent harmful effects of Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 reported by Schmidt et al., Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 56:221–228 (2009) were artifacts of poor study design and procedures. It is thus important that decision-makers evaluate the quality of individual scientific studies and do not view all as equally rigorous and relevant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2009, genetically engineered (GE) maize expressing insecticidal Cry proteins derived from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) was grown on more than 35 million hectares worldwide (James 2009). Most of the Bt maize varieties express either Cry1Ab for the control of stemborers, such as the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) (events MON810 and Bt11), or Cry3Bb1 for the control of corn rootworms (Diabrotica spp.; Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) (events MON863 and MON88017) (Hellmich et al. 2008; CERA 2010).

Before their commercial release, GE crops must undergo an environmental risk assessment to ensure that they do not cause unacceptable detrimental effects to the environment. In the case of insecticidal GE crops, one focus of the risk assessment is the potential adverse impact on non-target arthropods. The regulatory non-target risk assessment should follow a tiered approach, where the assessment increases in complexity and realism based on the knowledge gained during previous tests (Garcia-Alonso et al. 2006; Rose 2007; Romeis et al. 2008). Initial toxicity studies are conducted under controlled conditions in the laboratory and adopt certain quality criteria to ensure that the study can be reconstructed and that the results can be reasonably interpreted and repeated (Romeis et al. 2008). These criteria include confirmation of the validity of the testing procedure (e.g., a low control mortality in the untreated test organism) as well as information on the test compound (e.g., concentration tested and biological activity of the insecticidal protein).

One focus of the research on non-target arthropods has been on beneficial species such as those contributing to the biological control of herbivores, including predatory ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). For the two most common Cry proteins expressed in Bt maize varieties, i.e., Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1, laboratory studies for regulatory purposes have indicated no detrimental effects on the ladybird beetles Coleomegilla maculata (DeGeer) and Hippodamia convergens Guérin-Méneville exposed to protein concentrations several times higher than those expected in the field (US EPA 2001, 2003; Duan et al. 2002). In addition, a number of peer-reviewed laboratory studies in which ladybird beetles were fed Cry1Ab- or Cry3Bb1-expressing maize material (pollen) or Bt maize-fed herbivores have revealed no negative effects on different life-history parameters of C. maculata (Pilcher et al. 1997; Lundgren and Wiedenmann 2002; Ahmad et al. 2006) or Stethorus punctillum (Weise) (Álvarez-Alfageme et al. 2008; Li and Romeis 2010). However, one study reported inconclusive results for Cry1Ab effects on larvae of Cheilomenes sexmaculatus (Linnaeus) (Dhillon and Sharma 2009). The authors detected direct toxic effects in some bioassays, but no effect in others and no convincing explanation was presented for the observed differences. That ladybird beetle populations are not adversely affected by Bt maize has been confirmed in numerous field studies, both with maize varieties expressing Cry1Ab (e.g., Musser and Shelton 2003; Daly and Buntin 2005; de la Poza et al. 2005; Pilcher et al. 2005; Rose and Dively 2007) and with maize varieties expressing Cry3Bb1 (e.g., Bhatti et al. 2005; Ahmad et al. 2006; Rauschen et al. 2010). Overall, the large body of published literature provides no indication that the currently grown Bt maize varieties cause direct adverse effects on arthropods that are not closely taxonomically related to the target pest (Romeis et al. 2006; Wolfenbarger et al. 2008; Meissle and Romeis 2008; Naranjo 2009; Ricroch et al. 2010; Duan et al. 2010).

A recent study by Schmidt et al. (2009), however, raised concern in the scientific and regulatory communities because it reported toxicity of Escherichia coli-produced recombinant Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb to first-instar Adalia bipunctata (Linnaeus), a two-spotted ladybird beetle species that predominantly feeds on aphids but that also consumes other soft-bodied arthropods and pollen (Hodek and Honěk 1996). The study was, among others, subsequently cited by the German authorities as new scientific evidence for potential environmental harm to justify the suspension of Bt maize (event MON810) cultivation in 2009 (BVL 2009). The results of the study have been questioned because of methodological shortcomings that undermine the study’s inferences and that also prevent the reconstruction of the study (Meissle and Romeis 2008; Rauschen 2010; Ricroch et al. 2010). Schmidt et al. (2009) exposed larvae of A. bipunctata to the Cry proteins deposited on the outside of Ephestia kuehniella Zeller (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) eggs. Given that young ladybird larvae do not consume entire prey items but instead puncture the prey and suck out the contents (Banks 1957; Hagen 1962; Hodek and Honěk 1996), it is questionable whether the test insects actually ingested the insecticidal proteins. Furthermore, the control mortality in the first larval instar was very high (21%), indicating the unsuitability of the bioassay set-up.

We have thus conducted a set of experiments to determine whether A. bipunctata larvae are adversely affected by Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 at levels above those to which the predator larvae would be exposed to in a Bt maize field. In an initial experiment, we investigated whether young A. bipunctata larvae consume whole E. kuehniella eggs and ingest test compounds deposited on the outside of the egg shell. We then performed tritrophic studies to test whether early instar A. bipunctata are sensitive to Bt maize-expressed Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 (events MON810 and MON88017, respectively) when delivered through prey herbivores. The spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae), was selected as the carrier because among arthropod prey of A. bipunctata, this species is known to contain the highest concentrations of Cry proteins when fed on Bt maize (Dutton et al. 2002; Obrist et al. 2006a; Meissle and Romeis 2009a; Li and Romeis 2010). In a final experiment, A. bipunctata larvae were directly fed with purified Cry proteins at a concentration that was approximately 10 times higher than that detected in the Bt maize-fed spider mites.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Two transgenic maize varieties, DKc3421Bt (event MON810) and DKc5143Bt (event MON88017), both from Monsanto Company (St. Louis, MO, USA), and their corresponding non-transformed near isolines, DKc3421 and DKc5143, were used for the experiments. DKc3421Bt plants express a truncated, synthetic version of the cry1Ab gene from B. thuringiensis ssp. kurstaki HD-1, targeting Lepidoptera, while DKc5143Bt plants express a synthetically modified cry3Bb1 gene from wild-type B. thuringiensis ssp. kumamotoensis EG4691, targeting Coleoptera (CERA 2010). Bt expression levels in the plants used for the experiments were measured using double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (DAS-ELISA) from Agdia (Elkhard Indiana, USA) (see below for details).

The four maize varieties were grown simultaneously under the same environmental conditions of 25 ± 1°C, 70 ± 5% RH, and a 16-h photoperiod. Different growth chambers were used for transgenic and non-transgenic maize plants to prevent spider mites from moving between treatments. Three seeds were planted in one plastic pot (12 l) filled with humus-rich soil (Ökohum-Staudenerde, Obi-Ter, Märwil, Switzerland). Plants were fertilized weekly with 400–800 ml of a 0.2% aqueous solution of Vegesan standard (80 g N, 70 g P2O5, and 80 g K2O per liter, Hauert HBG Dünger AG, Grossaffoltern, Switzerland) and watered as required.

Maize plants were used for the spider mite rearing once they had reached the 4–5 leaf stage and were removed when they reached anthesis.

Arthropod material

Mixed stages of two arthropod species and eggs of a third species were used as prey for A. bipunctata. The two-spotted spider mite, T. urticae, was reared on Bt maize or the corresponding control plants in the growth chambers where the plants were raised. A colony of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris) (Hemiptera: Aphididae), was kept as a continuous culture on broad bean plants (Vicia faba L.) in the glasshouse at 22 ± 3°C, 70 ± 5% RH, and a 16-h photoperiod. UV-irradiated eggs of the lepidopteran E. kuehniella were supplied by Biotop (Valbonne, France) and stored at 4°C. Mixed stages of A. pisum and eggs of E. kuehniella, both of which are high quality food for A. bipunctata larvae (Blackman 1967; De Clercq et al. 2005), were used to determine the food quality of mixed stages of T. urticae for A. bipunctata larvae.

Eggs of A. bipunctata were purchased from Andermatt Biocontrol (Grossdietwil, Switzerland). Upon arrival, egg masses were placed in Petri dishes (9 cm diameter) and kept at 25 ± 1°C, 70 ± 5% RH, and a 16-h photoperiod until larvae emerged. Once larvae had eaten their egg shell and started searching for food (≈12 h old), they were individually transferred to the experimental arenas and offered a single egg of E. kuehniella to enhance larval survival. After about 8 h, larvae were switched to their respective prey treatments.

Insecticidal compounds

Stock solutions of purified Cry1Ab in 25 mM carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 10.6) and Cry3Bb1 in 10 mM sodium carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 10.0) were provided by Monsanto Company. The Cry1Ab protein used for the bioassays was the purified trypsin-resistant core of Cry1Ab from recombinant B. thuringiensis strain SIC1837. The Cry3Bb1 protein used was the purified Cry3Bb1.11098(Q349R) produced by recombinant E. coli containing the pMON72735 expression plasmid. Both proteins were purified using SDS–Page/Densitometry. The Cry3Bb1 protein is equivalent to protein expressed in Bt maize (events MON863 and MON88017) in terms of biochemical or toxical characteristics (US EPA 2007). The purity-corrected Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 protein concentration was 2.1 and 6.3 mg ml−1, respectively. Bioactivity of both Cry proteins was confirmed by Monsanto Company in sensitive insect bioassays (unpublished information, provided with the protein certificate of analysis). Cry1Ab was tested on larvae of Helicoverpa zea (Boddie) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and a 50% effect (EC50) on larval weight was reported for 0.012 μg trypsin resistant core. Cry3Bb1 was tested on larvae of Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) and a concentration causing 50% mortality (LC50) of 0.4 μg protein was reported. In addition, the bioactivity of the Cry3Bb1 protein was confirmed in a L. decemlineata bioassay in our laboratory (Meissle and Romeis 2009a).

Lyophilized snowdrop lectin (Galanthus nivalis agglutinin, GNA) was obtained from Els van Damme (Ghent University, Belgium). A detailed description of the isolation from snowdrop bulbs is given by Van Damme et al. (1987).

The inorganic toxin potassium arsenate was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Buchs, Switzerland).

Bioassay set-up

Experimental arenas consisted of small plastic Petri dishes (5 cm diameter, 1.3 cm height) covered with lids containing a mesh window (0.5 cm diameter with 0.2 mm openings) for ventilation. All experiments were conducted in a climate chamber at 25 ± 1°C, 70 ± 5% RH, and a 16-h photoperiod.

Consumption of E. kuehniella eggs by A. bipunctata

Visual observations were conducted to determine how young A. bipunctata larvae feed on E. kuehniella eggs. First and second instars of A. bipunctata were offered undamaged eggs and were observed with a stereomicroscope. Furthermore, the number of E. kuehniella eggs consumed during the first two instars was determined. Neonate A. bipunctata were fed daily ad libitum with undamaged E. kuehniella eggs, and the depleted egg shells were counted daily until A. bipunctata reached the third instar. Before eggs were provided to the predator, they were examined with a stereomicroscope, and damaged eggs were removed. The assay was performed using eight larvae.

Assessment of prey quality

A bioassay was conducted to investigate whether A. bipunctata larvae are able to develop by feeding exclusively on T. urticae. Neonates of A. bipunctata were fed ad libitum with one of the following food sources: E. kuehniella eggs or mixed stages (immatures and adults) of A. pisum or T. urticae. Mixed stages of A. pisum were brushed from bean leaves and added to the test arenas. For T. urticae, an approximately 9-cm2 maize (Dkc5143) leaf disc infested with spider mites was placed upside-down in each Petri dish. All food sources were replaced daily. The experiment was performed with 30 A. bipunctata larvae per treatment. Assessment of variables is described in the next section.

Tritrophic feeding study

This bioassay assessed the prey-mediated effects of Bt protein-expressing maize on A. bipunctata. Neonates were fed ad libitum with T. urticae reared on Bt-transgenic plants or on the respective non-transformed near isolines for several generations as described above. The bioassay was conducted in three subsequent runs with 15 replications each, resulting in a total of 45 A. bipunctata larvae per treatment. For every run, the A. bipunctata larvae were obtained from a different shipment and were fed with T. urticae reared on different plants.

In both the prey-quality and tritrophic feeding assays, A. bipunctata larvae were observed twice daily, in the morning and in the evening, until they reached the third instar. Then, larvae were frozen at −20°C, dried at 50°C for 24 h, and subsequently weighed on a microbalance (Mettler Toledo MX5, division d = 1 μg; tolerance ± 2 μg). Larval development time (L1–L3), dry weight of third-instars, and mortality were measured. We focused on the early larval instars for three main reasons: (1) early instars are generally regarded as being more sensitive to Bt Cry proteins than older instars or adults (Glare and O’Callaghan 2000), (2) T. urticae are not an optimum food for A. bipunctata larvae, and extended feeding on T. urticae would have caused unacceptably high control mortality levels, and (3) Schmidt et al. (2009) only reported Cry protein effects on the first instar in their bioassays.

Verification of the transfer of Cry proteins through the food chain

This experiment was conducted to verify that A. bipunctata larvae were exposed to Cry protein when feeding on Bt maize-fed spider mites and to quantify the protein levels. Samples of maize leaves and T. urticae were collected from Bt plants. Spider mites were collected in a tray kept below a maize leaf by shaking the leaf with a stick. Maize leaf material and T. urticae obtained from the 7th leaf from one plant were separately put into 1.5-ml micro-reaction tubes. For each of the three runs, two samples of leaves and T. urticae (7–10 mg fresh weight) were collected from different maize plants, resulting in a total of six samples. Leaf material and T. urticae were similarly obtained from control plants.

Neonate A. bipunctata were fed Bt maize-reared T. urticae for either 2 or 5 days, equivalent to first and second larval instars, respectively. As a control, larvae were fed T. urticae raised on non-transgenic maize plants. Five A. bipunctata were pooled into a 1.5-ml micro-reaction tube as one sample; for each of the three runs, two samples of both larval instars were analyzed.

All plant and insect samples were frozen and stored at −20°C for less than 11 weeks for Cry1Ab or Cry3Bb1 measurements. Bt protein levels in maize leaves, T. urticae, and A. bipunctata were measured using DAS-ELISA from Agdia following the protocol described in detail in Meissle and Romeis (2009b). Standard curves were made using solutions of the purified Cry1Ab or Cry3Bb1 proteins that were provided by Monsanto Company and for which purity was known. Protein concentrations in μg g−1 fresh weight (FW) were calculated from the standard curves using regression analysis. For the clear separation of positive readings from controls, the limit of detection (LOD) of the test was determined based on the standard deviation of the OD values of buffer-only controls multiplied by three (ICH 2005). Subsequently, the detection limit of each sample was calculated from the dilution, sample weight and amount of added buffer. Measurements of all Bt samples revealed ODs above the respective LOD.

Direct feeding study

A direct feeding study was conducted to evaluate the effect of purified Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 proteins on the pre-imaginal development of A. bipunctata and the weight of the emerging adult beetles. The bioassay aimed to cover some of the limitations of the tritrophic experiment that used T. urticae as a carrier for the Cry proteins, namely (1) T. urticae is a suboptimum food for A. bipunctata, (2) the tritrophic experiment had to be restricted to the first two intars of A. bipunctata, and (3) we could not include a positive control to show that the experimental set-up was able to detect adverse effects on the life-history parameters that were measured.

Bt protein concentrations were approximately 10 times higher than those measured in spider mites that had fed on Bt maize. Snowdrop lectin (GNA) and potassium arsenate were used as positive control treatments. That GNA can have a deleterious effect on larvae of A. bipunctata at high concentrations has been previously demonstrated (Hogervorst et al. 2006), and potassium arsenate is an inorganic compound that is highly toxic to insects and that is often used as a positive control in toxicological studies including those with ladybird beetles (Duan et al. 2002, 2006, 2008). The aim of the positive controls was to show that the ladybird larvae actually ingested the sucrose solution containing the test compounds and that the experimental set-up was able to detect adverse effects on the measured life-history parameters (Rose 2007).

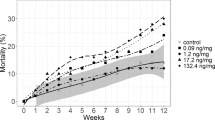

The experiment was initiated with neonate A. bipunctata. Each larva received two droplets of a 2 M sucrose solution that was prepared with deionized water (L1 and L2: 0.5 μl, L3 and L4: 1 μl) or a sucrose solution containing 45 μg ml−1 Cry1Ab, 200 μg ml−1 Cry3Bb1, 10,000 μg ml−1 GNA, or 300 μg ml−1 potassium arsenate on the first day of each instar. After 24 h, larvae were transferred to clean Petri dishes and subsequently fed ad libitum with E. kuehniella eggs to continue development. After emergence, adults were frozen at −20°C and later dried at 50°C for 24 h. Subsequently, the dried adults were weighed on the microbalance and their sex was determined by dissection. Larval and pupal development time, adult dry weight, and mortality were recorded. The experiment was conducted with 34–41 A. bipunctata larvae per treatment.

Statistical analysis

In the assay in which A. bipunctata was fed with three different prey species, larval development time (L1–L3) and L3 dry weight were analysed using non-parametric statistics because data were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Three pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test, adjusted for ties, and significance levels were adjusted using the sequential Bonferroni procedure (Holm 1979). In the experiment that determined the impact of Bt-expressing maize on A. bipunctata, data for larval development time (L1–L3) and L3 dry weight were compared between the Bt maize and the respective non-Bt maize treatments using Student’s t-test.

In the direct feeding assay, larval and pupal development time and adult dry weight were analyzed between the control treatment and the respective insecticidal compounds in pairwise comparisons using Student’s t-test. Significance levels were adjusted using the sequential Bonferroni procedure.

In all assays, mortality data were compared using Chi-square tests. Again, significance levels were adjusted using the sequential Bonferroni procedure to correct for multiple pairwise comparisons.

For all tests, the overall α-level was set at 5%. Statistical analyses were conducted using the software package Statistica (Version 7.1, StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

Statistical power analyses were performed before conducting the tritrophic feeding study using PASS (Version 2005, NCCS, Kaysville, UT, USA). Data (mean and standard deviation) recorded for the A. bipunctata larvae fed with T. urticae in the prey-quality bioassay were used for the calculations. With 45 replications, a power of 80%, and α = 0.05, the detectable differences between control and Bt treatment for larval development time (L1–L3), L3 dry weight, and larval mortality were 12, 8, and 29%, respectively. Calculations were based on two-sided t-tests (larval development time and weight) or Chi-square tests (mortality). The sensitivity of the experiment was judged to be sufficient because 80% power at α = 0.05 to detect a 50% effect is often stated as acceptable for risk assessment research (Rose 2007; EFSA 2009). Power analyses were not conducted for the direct feeding bioassay because the positive control treatments that were included provide some indication about the size of the detectable effect in that bioassay.

Results

Visual observations revealed that, when preying on E. kuehniella eggs, both first and second instars of A. bipunctata sucked out their contents until they were completely depleted. No larva was observed consuming whole eggs or even parts of the egg shell. During the first instar, a single A. bipunctata larva consumed the contents of 41.0 ± 3.26 (mean ± SE) E. kuehniella eggs. The average egg consumption of a second instar was 56.3 ± 6.26. In no case did the larvae consume the egg shell. Thus, young A. bipunctata larvae cannot be dosed with test compounds deposited on the outside of E. kuehniella eggs.

A comparison among different prey items revealed that mixed stages of A. pisum and E. kuehniella eggs were of high and equal quality as prey for A. bipunctata resulting in similar larval development time, weight, and mortality (Table 1). Although A. bipunctata larvae were also able to reach the third instar when exclusively fed mixed stages of T. urticae, development time (L1–L3) was doubled, L3 larval weight was halved, and mortality was increased >5-fold (but not significantly) when A. bipunctata consumed T. urticae instead of A. pisum or E. kuehniella eggs. The results revealed that spider mites are suitable carriers to expose the first two larval instars of A. bipunctata to Bt maize-expressed Cry proteins.

When A. bipunctata larvae were fed exclusively with T. urticae that had been reared on Bt maize expressing Cry1Ab or Cry3Bb1, none of the recorded life-history parameters, i.e., development time (L1–L3), weight, and mortality, was significantly affected when compared to larvae that were fed T. urticae collected from the respective non-transformed control plants (Table 2).

That the A. bipunctata larvae had ingested Cry protein when feeding on Bt maize-fed T. urticae was confirmed in subsequent ELISA analyses (Table 3). While Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 were detected in Bt maize leaves, T. urticae reared on transgenic plants, and A. bipunctata fed with spider mites collected from Bt plants, a drastic reduction (>90%) of the Bt concentration through the food chain occurred for both proteins (Table 3). Neither Cry1Ab nor Cry3Bb1 protein was detected in any control sample of plant or insect material.

When purified Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 dissolved in a sucrose solution were fed directly to A. bipunctata larvae, no effect on any of the measured life-history parameters were detected (Table 4). In contrast, both positive controls (GNA and potassium arsenate) caused adverse effects on the A. bipunctata larvae, indicating the sensitivity of the bioassay set-up and the exposure of the larvae to the test compounds. Ingestion of potassium arsenate significantly increased the mortality of A. bipunctata larvae and pupae and prolonged the development of surviving larvae (Table 4). GNA also significantly prolonged larval development by almost 10% and caused a significant reduction (by 23%) in the dry weight of emerging male beetles.

Discussion

The current study provides no indication that larvae of A. bipunctata are adversely affected after ingestion of Cry1Ab or Cry3Bb1. A tritrophic bioassay in which first and second instars of A. bipunctata were fed Bt maize-fed spider mites provided no evidence that young larvae are sensitive to Bt maize-expressed Cry1Ab or Cry3Bb1. That the A. bipunctata larvae were exposed to plant-expressed Cry proteins in our tritrophic experiments was confirmed by ELISA. Compared to ladybird beetle larvae collected in Cry1Ab- or Cry3Bb1-expressing Bt maize fields (Harwood et al. 2005, 2007; Obrist et al. 2006b; Meissle and Romeis 2009b), the larvae in our bioassay contained considerably more Cry protein. For example, the first and second instars of A. bipunctata in the current study contained 164–329 times more Cry3Bb1 protein than the larvae of Coccinella septempunctata (Pallas) and Propylea quatuordecimpunctata (L.) collected in a field of the same Cry3Bb1-expressing Bt maize variety used in the present study (see supporting information, Table S1, in Meissle and Romeis 2009b). Our tritrophic experiments thus provided very conservative, worst-case exposure conditions. Because the Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 leaf-expression levels of the climate chamber-grown Bt maize plants used in our study were comparable to those reported from the field (Monsanto 2002, 2004; Nguyen and Jehle 2007, 2009), the conclusions drawn are applicable to the field situation.

Spider mites are an alternative prey for ladybird beetles including A. bipunctata, even though mites cannot support complete larval development (Robinson 1951). Our study showed that T. urticae is of lower nutritional quality than the aphid A. pisum or E. kuehniella eggs, both of which are known to be high quality food sources for A. bipunctata larvae (Blackman 1967; De Clercq et al. 2005). Nevertheless, feeding exclusively on T. urticae allowed A. bipunctata larvae to reach the third instar with mortality levels remaining below 20%. To keep mortality low, however, we had to feed neonate A. bipunctata a single egg of E. kuehniella before the start of the experiment. Preliminary observations had revealed that the provision of a single egg increased the ability of the neonates to capture spider mites and significantly reduced mortality (Álvarez-Alfageme et al., unpublished data). Dixon (1959) and Hurst and Majerus (1993) have shown that the chance of capturing prey increases for neonate ladybirds once the first prey has been eaten.

Bt maize-fed T. urticae are suitable carriers to expose A. bipunctata larvae to plant-expressed Cry proteins for three main reasons. First, the spider mites contain high concentrations of Cry protein when fed Bt maize. In our study, T. urticae contained more than 50% of the Cry protein concentration found in green leaf tissue. Similar or even higher Cry protein levels have been reported in previous studies with different Bt maize events (Dutton et al. 2002; Obrist et al. 2006a; Meissle and Romeis 2009a; Li and Romeis 2010). Second, T. urticae is not itself affected when feeding on Cry1Ab- or Cry3Bb1-expressing Bt maize (Dutton et al. 2002; Li and Romeis 2010), and this excludes potential indirect effects on the predator that may be caused by changes in prey quality (see Romeis et al. 2006 and Naranjo 2009 for a discussion of such prey-quality mediated effects). Third, sensitive insect bioassays have confirmed that Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 remain biologically active after ingestion by T. urticae when feeding on Bt maize (Obrist et al. 2006a; Meissle and Romeis 2009a). Spider mites might thus be used as a carrier of plant-expressed insecticidal proteins to expose other predators that are known to feed occasionally on this herbivore. This has already been documented for larvae of the green lacewing Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) (Dutton et al. 2002; Obrist et al. 2006a).

Even though the tritrophic feeding experiment provided no evidence that Bt maize-expressed Cry1Ab or Cry3Bb1 detrimentally affect A. bipunctata larvae, a confirmatory experiment was conducted using purified Cry proteins at a concentration that was approximately 10 times higher than measured in the Bt maize-fed T. urticae. Larvae were dosed with the test compounds dissolved in a sucrose solution only during the first day of each larval instar. They subsequently received ad libitum E. kuehniella eggs as food because the larvae would not be able to develop on sucrose solution alone. A similar set-up has been used to conduct direct toxicity tests with larvae of C. carnea (Lawo and Romeis 2008). The results confirmed our previous findings that ingestion of either of the two Cry proteins does not harm A. bipunctata larvae. In contrast to the tritrophic experiment, the direct feeding experiment involved all larval instars and the pupal stage (in terms of development time and mortality) and the adults (in terms of weight at emergence) of A. bipunctata. Two positive control treatments that were tested in parallel confirmed that the predator larvae had ingested the test compounds and that the bioassay was sensitive enough to detect adverse effects on larval mortality, development time and adult weight. The GNA treatment revealed that even a 10% prolongation of the larval development time and a 23% reduction in adult weight were detectable.

The results obtained in our experiments contradict those of Schmidt et al. (2009), who reported direct toxic effects of purified Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 proteins to first-instar A. bipunctata. One possibility for this contradiction is differences in the protein exposure levels. While we confirmed and quantified the ingestion of Cry proteins by A. bipunctata larvae in our experiments, the dose that the larvae ingested in Schmidt et al. (2009) was not measured and remains unclear. Schmidt et al. (2009) fed the ladybird larvae with eggs of E. kuehniella that had been sprayed with a water solution containing the dissolved Cry proteins. While the protein concentration of the solution was indicated, the authors did not provide information on the amount of protein solution sprayed on the E. kuehniella eggs, the residual Cry protein concentration on the treated eggs, or the amount of treated eggs consumed by the A. bipunctata larvae. It is thus impossible to calculate the dose with which larvae were treated in Schmidt et al. (2009). Another confusing factor about the Schmidt et al. (2009) study is that young coccinellid larvae are known to bite into their prey (aphids and insect eggs) and suck out the contents (Banks 1957; Hagen 1962; Hodek and Honěk 1996). Our visual observations demonstrated that this is also the case for first and second instars of A. bipunctata when provided eggs of E. kuehniella. Consequently, uptake of test compounds deposited on the outside of the E. kuehniella egg shell was probably very low in Schmidt et al. (2009), especially for first instar A. bipunctata, for which the detrimental effects of Cry proteins were observed. Therefore, the possibility that factors other than direct toxicity of the two Cry proteins were responsible for the reported effects is likely.

In addition to these shortcomings, additional weaknesses in Schmidt et al. (2009) have been pointed out in three other publications (Meissle and Romeis 2008; Rauschen 2010; Ricroch et al. 2010). First, the authors did not observe a relationship between the Cry protein concentration and the measured mortality. Second, the only effect seen was mortality; no sublethal effects for surviving A. bipunctata were reported on larval development time or A. bipunctata body weight. Third, the larvae suffered an unusually high and variable control mortality. In the three experiments, first-instar A. bipuncata suffered control mortalities ranging from 7.5 to 20.8%. This is unexpectedly high given the fact that E. kuehniella eggs are generally regarded as high quality food for A. bipunctata (De Clercq et al. 2005) and points to methodological problems in the bioassay. Our results support this: first-instar A. bipunctata suffered a mortality of only 3% when fed exclusively with E. kuehniella eggs.

Our study is in accordance with a range of laboratory studies that have reported a lack of direct toxic effects of Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 on different species of ladybird beetles (Pilcher et al. 1997; US EPA 2001, 2003; Duan et al. 2002; Lundgren and Wiedenmann 2002; Ahmad et al. 2006; Álvarez-Alfageme et al. 2008; Li and Romeis 2010). A recent direct feeding study with trypsin-activated Cry1Ab has also revealed no toxic effects on A. bipunctata larvae (Porcar et al. 2010). In addition, exposure to the Cry proteins in the field is generally low for ladybird beetles that use aphids as their major food source given that aphids ingest no or only trace amounts of Cry proteins when feeding on Bt maize (Raps et al. 2001; Head et al. 2001; Dutton et al. 2002; Lundgren and Wiedenmann 2005; Meissle and Romeis 2009b; Romeis and Meissle 2010). Under field conditions, significant exposure only seems to occur for species such as S. punctillum that specifically feed on spider mites (Obrist et al. 2006b) or for species such as C. maculata that consume large amounts of maize pollen (Lundgren et al. 2005). The lack of toxicity together with generally low exposure levels indicates a negligible risk of the current Bt maize varieties to ladybird beetles, and this has been confirmed in various field studies (e.g., Musser and Shelton 2003; Bhatti et al. 2005; Daly and Buntin 2005; de la Poza et al. 2005; Pilcher et al. 2005; Ahmad et al. 2006; Rose and Dively 2007; Rauschen et al. 2010).

Importance of study design

Laboratory toxicity studies are important for assessing potential non-target effects of insecticidal GE crops (Garcia-Alonso et al. 2006; Rose 2007; Romeis et al. 2008; Duan et al. 2010). Such studies must be properly designed and executed to maximize the probability that compounds with adverse effects are detected. The confidence in the conclusions drawn from those laboratory studies thus depends on the study’s ability to detect such adverse effects, if present.

Using spider mites as a carrier of Cry proteins, we exposed first and second instars of A. bipunctata to unrealistically high levels of biologically active, plant-expressed Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1. The larvae were not adversely affected by the two Cry proteins. This was confirmed in a second bioassay where A. bipunctata larvae were fed with purified Cry proteins dissolved in a sucrose solution at a concentration approximately 10 times higher than in the Bt maize-fed spider mites. Our confidence in the conclusion that Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 at plant-expression levels do not adversely affect larvae of A. bipunctata is high because (1) the A. bipunctata larvae were exposed to and ingested concentrations of the test compounds that were several times higher than the predicted exposures in the field; (2) the ingested Cry proteins were biologically active; (3) the negative control mortality in both the tri-trophic experiment and in the direct feeding study were acceptable, showing the suitability of the bioassay set-up; and (4) statistical power analyses or positive control treatments confirmed the sensitivity of our test systems for detecting adverse effects of the test compounds on the measured A. bipunctata life-history parameters.

Our results show that the harmful effects of the two Cry proteins reported in Schmidt et al. (2009) were likely false positives, i.e., artifacts of poor study design and procedures. This shows the importance of following minimum quality standards in conducting laboratory non-target studies for assessing the environmental risk of GE crops. It is thus important that decision-makers evaluate the quality of individual scientific studies and do not view the conclusions of all studies as equally trustworthy, a fact that has for example been explicitly stated by the Australian Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (OGTR 2009). Consequently, not all peer-reviewed scientific studies are equally relevant for environmental risk assessment and decision-making.

References

Ahmad A, Wilde GE, Whitworth RJ, Zolnerowich G (2006) Effect of corn hybrids expressing the coleopteran-specific Cry3Bb1 protein for corn rootworm control on aboveground insect predators. J Econ Entomol 99:1085–1095

Álvarez-Alfageme F, Ferry N, Castañera P, Ortego F, Gatehouse AMR (2008) Prey mediated effects of Bt maize on fitness and digestive physiology of the red spider mite predator Stethorus punctillum Weise (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Transgenic Res 17:943–954

Banks CJ (1957) The behaviour of individual coccinellid larvae on plants. Br J Anim Behav 5:12–24

Bhatti MA, Duan J, Head GP, Jiang C, McKee MJ, Nickson TE, Pilcher CL, Pilcher CD (2005) Field evaluation of the impact of corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)-protected Bt corn on foliage-dwelling arthropods. Environ Entomol 34:1336–1345

Blackman RL (1967) The effects of different aphid foods on Adalia bipunctata L. and Coccinella 7-punctata L. Ann appl Biol 59:207–219

BVL (2009) Bekanntmachung eines Bescheides zur Beschränkung des Inverkehrbringens von gentechnischen veränderten Mais der Linie MON810. Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety (BVL), Berlin, Germany. http://www.bvl.bund.de/cln_027/DE/08__PresseInfothek/00__doks__downloads/mon__810__bescheid,templateId=raw,property=publicationFile.pdf/mon_810_bescheid.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2010

CERA (2010) GM Crop Database. Center for Environmental Risk Assessment (CERA), Washington, DC. http://cera-gmc.org/index.php?action=gm_crop_database. Accessed 6 July 2010

Daly T, Buntin GD (2005) Effects of Bacillus thuringiensis transgenic corn for lepidopteran control on non-target arthropods. Environ Entomol 34:1292–1301

De Clercq P, Bonte M, Van Speybroeck K, Bolckmans K, Deforce K (2005) Development and reproduction of Adalia bipunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) on eggs of Ephestia kuehniella (Lepidoptera: Phycitidae) and pollen. Pest Manag Sci 61:1129–1132

De la Poza M, Pons X, Farinós GP, López C, Ortego F, Eizaguirre M, Castañera P, Albajes R (2005) Impact of farm-scale Bt maize on abundance of predatory arthropods in Spain. Crop Prot 24:677–684

Dhillon MK, Sharma HC (2009) Effects of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxins Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac on the coccinellid beetle, Cheilomenes sexmaculatus (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae) under direct and indirect exposure conditions. Biocontr Sci Technol 19:407–420

Dixon AFG (1959) An experimental study of the searching behaviour of the predatory coccinellid beetle Adalia decempunctata (L.). J Anim Ecol 28:259–281

Duan JJ, Head G, McKee MJ, Nickson TE, Martin JW, Sayegh FS (2002) Evaluation of dietary effects of transgenic corn pollen expressing Cry3Bb1 protein on a non-target ladybird beetle, Coleomegilla maculata. Ent Exp Appl 104:271–280

Duan JJ, Paradise MS, Lundgren JG, Bookout JT, Jian C, Wiedenmann RN (2006) Assessing non-target impacts of Bt corn resistant to corn rootworms: Tier-1 testing with larvae of Poecilus chalcites (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Environ Entomol 35:135–142

Duan JJ, Teixeira D, Huesing JE, Jiang C (2008) Assessing the risk to nontarget organisms from Bt corn resistant to corn rootworms (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae): Tier-I testing with Orius insidiosus (Heteroptera: Anthocoridae). Environ Entomol 37:838–844

Duan JJ, Lundgren JG, Naranjo S, Marvier M (2010) Extrapolating non-target risk of Bt crops from laboratory to field. Biol Lett 6:74–77

Dutton A, Klein H, Romeis J, Bigler F (2002) Uptake of Bt-toxin by herbivores feeding on transgenic maize and consequences for the predator Chrysoperla carnea. Ecol Entomol 27:441–447

EFSA (2009) Statistical considerations for the safety evaluation of GMOs. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Parma. http://www.efsa.europa.eu/EFSA/efsa_locale-1178620753812_1211902768517.htm. Accessed 6 July 2010

Garcia-Alonso M, Jacobs E, Raybould A, Nickson TE, Sowig P, Willekens H, Van der Kouwe P, Layton R, Amijee F, Fuentes AM, Tencalla F (2006) A tiered system for assessing the risk of genetically modified plants to non-target organisms. Environ Biosafety Res 5:57–65

Glare TR, O’Callaghan M (2000) Bacillus thuringiensis: biology, ecology and safety. Wiley, Chichester

Hagen KS (1962) Biology and ecology of predaceous Coccinellidae. Annu Rev Entomol 7:289–326

Harwood JD, Wallin WG, Obrycki JJ (2005) Uptake of Bt endotoxins by nontarget herbivores and higher order arthropod predators: molecular evidence from a transgenic corn agroecosystem. Mol Ecol 14:2815–2823

Harwood JD, Samson RA, Obrycki JJ (2007) Temporal detection of Cry1Ab-endotoxins in coccinellid predators from fields of Bacillus thuringiensis corn. Bull Ent Res 97:643–648

Head G, Brown CR, Groth ME, Duan JJ (2001) Cry1Ab protein levels in phytophagous insects feeding on transgenic corn: implications for secondary exposure risk assessment. Ent Exp Appl 99:37–45

Hellmich RL, Albajes R, Bergvinson D, Prasifka JR, Wang ZY, Weiss MJ (2008) The present and future role of insect-resistant genetically modified maize in IPM. In: Romeis J, Shelton AM, Kennedy GG (eds) Integration of insect-resistant genetically modified crops within IPM programs. Springer, New York, pp 119–158

Hodek I, Honěk A (1996) Ecology of Coccinellidae. Kluwer, Dordrecht

Hogervorst PAM, Ferry N, Gatehouse AMR, Wäckers FL, Romeis J (2006) Direct effects of snowdrop lectin (GNA) on larvae of three aphid predators and fate of GNA after ingestion. J Insect Phys 52:614–624

Holm S (1979) A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 6:65–70

Hurst GDD, Majerus MEN (1993) Why do maternally inherited microorganisms kill males? Heredity 71:81–95

ICH (2005) Harmonised tripartite guideline: validation of analytical procedures: Text and methodology Q2(R1). In: International conference on harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. http://www.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA417.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2010

James C (2009) Global status of commercialized biotech/GM crops: 2009. ISAAA Brief No. 41. ISAAA, Ithaca, NY

Lawo NC, Romeis J (2008) Assessing the utilization of a carbohydrate food source and the impact of insecticidal proteins on larvae of the green lacewing, Chrysoperla carnea. Biol Contr 44:389–398

Li Y, Romeis J (2010) Bt maize expressing Cry3Bb1 does not harm the spider mite, Tetranychus urticae, or its ladybird beetle predator, Stethorus punctillum. Biol Contr 53:337–344

Lundgren JG, Wiedenmann RN (2002) Coleopteran-specific Cry3Bb toxin from transgenic corn pollen does not affect the fitness of a nontarget species, Coleomegilla maculata DeGeer (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Environ Entomol 31:1213–1218

Lundgren JG, Wiedenmann RN (2005) Tritrophic interactions among Bt (Cry3Bb1) corn, aphid prey, and the predator Coleomegilla maculata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Environ Entomol 34:1621–1625

Lundgren JG, Huber A, Wiedenmann RN (2005) Quantification of consumption of corn pollen by the predator Coleomegilla maculata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) during anthesis in an Illinois cornfield. Agric For Entomol 7:53–60

Meissle M, Romeis J (2008) Compatibility of biological control with Bt maize expressing Cry3Bb1 in controlling corn rootworms. In: Mason PG, Gillespie DR, Vincent C (eds). Proceedings of the third international symposium on biological control of arthropods, Christchurch, New Zealand, 8–13 February 2009, FHTET-2008-06, Morgantown, WV, United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, pp 145–160. http://www.biocontrol.ucr.edu/ISBCA/3. Accessed 6 July 2010

Meissle M, Romeis J (2009a) Insecticidal activity of Cry3Bb1 expressed in Bt maize on larvae of the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Ent Exp Appl 131:308–319

Meissle M, Romeis J (2009b) The web-building spider Theridion impressum (Araneae: Theridiidae) is not adversely affected by Bt maize resistant to corn rootworms. Plant Biotech J 7:645–656

Monsanto (2002) Safety assessment of YieldGard® Insect-Protected Corn Event MON 810. http://www.agbios.com/docroot/decdocs/02-269-010.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2010

Monsanto (2004) Petition for the determination of nonregulated status for MON88017 corn. http://www.aphis.usda.gov/brs/aphisdocs/04_12501p.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2010

Musser FR, Shelton AM (2003) Bt sweet corn and selective insecticides: Impacts on pests and predators. J Econ Entomol 96:71–80

Naranjo SE (2009) Impacts of Bt crops on non-target invertebrates and insecticide use patterns. CAB reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources 4, No. 011. doi:10.1079/PAVSNNR20094011

Nguyen HT, Jehle JJ (2007) Quantitative analysis of the seasonal and tissue-specific expression of Cry1Ab in transgenic maize Mon810. J Plant Dis Prot 114:82–87

Nguyen HT, Jehle JJ (2009) Expression of Cry3Bb1 in transgenic corn MON88017. J Agric Food Chem 57:9990–9996

Obrist L, Dutton A, Romeis J, Bigler F (2006a) Biological activity of Cry1Ab toxin expressed by Bt maize following ingestion by herbivorous arthropods and exposure of the predator Chrysoperla carnea. Biocontrol 51:31–48

Obrist LB, Dutton A, Albajes R, Bigler F (2006b) Exposure of arthropod predators to Cry1Ab toxin in Bt maize fields. Ecol Entomol 31:143–154

OGTR (2009) Risk analysis framework. Office of the Gene Technology Regulator, Canberra, Australia. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ogtr/publishing.nsf/Content/riskassessments-1. Accessed 6 July 2010

Pilcher CD, Obrycki JJ, Rice ME, Lewis LC (1997) Preimaginal development, survival, and field abundance of insect predators on transgenic Bacillus thuringiensis corn. Environ Entomol 26:446–454

Pilcher CD, Rice ME, Obrycki JJ (2005) Impact of transgenic Bacillus thuringiensis corn and crop phenology on five non-target arthropods. Environ Entomol 34:1302–1316

Porcar M, García-Robles I, Domínguez-Escribà L, Latorre A (2010) Effects of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ab and Cry3Aa endotoxins on predatory Coleoptera tested through artificial diet-incorporation bioassay. Bull Ent Res 100:297–302

Raps A, Kehr J, Gugerli P, Moar WJ, Bigler F, Hilbeck A (2001) Immunological analysis of phloem sap of Bacillus thuringiensis corn and of the non-target herbivore Rhopalosiphum padi (Homoptera: Aphididae) for the presence of Cry1Ab. Mol Ecol 10:525–533

Rauschen S (2010) A case of “pseudo science”? A study claiming effects of the Cry1Ab protein on larvae of the two-spotted ladybird is reminiscent of the case of the green lacewing. Transgenic Res 19:13–16

Rauschen S, Schaarschmidt F, Gathmann A (2010) Occurrence and field densities of Coleoptera in the maize herb layer: implications for environmental risk assessment of genetically modified Bt-maize. Transgenic Res 19. doi:10.1007/s11248-009-9351-3

Ricroch A, Bergé JB, Kuntz M (2010) Is the German suspension of MON810 maize cultivation scientifically justified? Transgenic Res 19:1–12

Robinson AG (1951) Annotated list of predators of tetranchid mites in Manitoba. Annu Rep Entomol Soc Ont 82:33–37

Romeis J, Meissle M (2010) Non-target risk assessment of Bt crops—cry protein uptake by aphids. J Appl Ent 134. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0418.2010.01546.x

Romeis J, Meissle M, Bigler F (2006) Transgenic crops expressing Bacillus thuringiensis toxins and biological control. Nat Biotechnol 24:63–71

Romeis J, Bartsch D, Bigler F, Candolfi MP, Gielkens MMC, Hartley SE, Hellmich RL, Huesing JE, Jepson PC, Layton R, Quemada H, Raybould A, Rose RI, Schiemann J, Sears MK, Shelton AM, Sweet J, Vaituzis Z, Wolt JD (2008) Assessment of risk of insect-resistant transgenic crops to nontarget arthropods. Nat Biotechnol 26:203–208

Rose RI (ed) (2007) White paper on tier-based testing for the effects of proteinaceous insecticidal plant-incorporated protectants on non-target invertebrates for regulatory risk assessment. US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/pips/non-target-arthropods.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2010

Rose R, Dively GP (2007) Effects of insecticide-treated and lepidopteran-active Bt transgenic sweet corn on the abundance and diversity of arthropods. Environ Entomol 36:1254–1268

Schmidt JEU, Braun CU, Whitehouse LP, Hilbeck A (2009) Effects of activated Bt transgene products (Cry1Ab, Cry3Bb) on immature stages of the ladybird Adalia bipunctata in laboratory ecotoxicity testing. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 56:221–228

US EPA (2001) Biopesticide registration action document: Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) plant-incorporated protectants. US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/pips/bt_brad.htm. Accessed 6 July 2010

US EPA (2003) Biopesticides registration action document: Event MON863 Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3Bb1 corn. US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. http://cera-gmc.org/docs/decdocs/07-156-003.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2010

US EPA (2007) Biopesticides registration action document. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3Bb1 corn. US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. http://epa.gov/opp00001/biopesticides/ingredients/tech_docs/cry3bb1/1_Cry3Bb1_health_characterization.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2010

Van Damme EJM, Allen AK, Peumans WJ (1987) Isolation and characterization of a lectin with exclusive specificity towards mannose from snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) bulbs. FEBS Lett 215:140–144

Wolfenbarger LL, Naranjo SE, Lundgren JG, Bitzer RJ, Watrud LS (2008) Bt crops effects on functional guilds of non-target arthropods: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 3(5):e2118. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002118

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mario Walburger for his assistance in providing and handling the arthropods. We also thank Patrick De Clercq (University of Ghent, Belgium), Michael Meissle (CSIRO Entomology, Brisbane, Australia), and Tony Shelton (Cornell University) for helpful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript. Further thanks go to Monsanto Company for providing Bt maize seeds and purified Cry protein solutions.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Álvarez-Alfageme, F., Bigler, F. & Romeis, J. Laboratory toxicity studies demonstrate no adverse effects of Cry1Ab and Cry3Bb1 to larvae of Adalia bipunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): the importance of study design. Transgenic Res 20, 467–479 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11248-010-9430-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11248-010-9430-5