Abstract

This study explores the relationship between the actual division of housework and men’s and women’s perceived fairness in this regard. The central question is how the actual sharing of housework influences the perceptions of fairness in the division of housework. It is hypothesised that the perceptions of fairness differ between policy models. In countries where gender equality has been more present on the political agenda and dual-earner policies have been introduced, people are expected to be more sensitive to an unfair sharing or division of housework. By analysing the relationship between actual division of housework and perceptions of fairness in household work for 22 countries representing different family policy models, the study takes on a comparative perspective with the purpose of analysing the normative impact of policy. The analysis draws on data from the 2002 round of the International Social Survey Programme on family and changing gender roles. The results show that in countries that have promoted gender equality through the introduction of policies with an aim to promote dual roles in work and family, both women and men are more sensitive to an unfair division of household labour. The difference between perceptions in the different policy models is greater among men than among women, indicating that a politicization of the dual-earner family is more important for men’s equity perceptions than women’s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Only the Dutch speaking part of Belgium (Flanders) participates in the ISSP.

The fact that the scales run in two directions equals out the effects of the control variables, which become falsely non-significant because of the nonlinear nature of the associations (positive and negative effects in different parts of the scale end up to a zero-result). In most previous research this is not a problem in practice as their analyses focus on women’s perceived fairness only (it is a problem on a conceptual level though as the measure theoretically still runs in two directions). As I also include men’s reports, which to a large extent are a mirror of women’s, the problem explicitly occurs. This recoding does not influence the main results; it only corrects for falsely non-significant effects of the control variables.

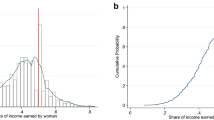

I have analysed the data using a categorical variant of the perceived fairness variable to see if the results differ according to whether the respondent perceives that he or she does more or less than his or her fair share of the household work. The results from that test shows that the perceptions of fairness are similar independent of which of the partners performs more or less than their fair share. Hence I chose to use the three level variant as a continuous variable.

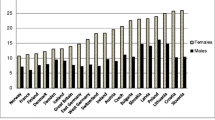

Country means for a modified version of the above described housework index are shown in the appendix, Fig. 6. The modified index ranges from −100, meaning that the partner always does all household chores, via 0 which stands for equal sharing, to +100 meaning that the respondent always does all the household chores. The bars in this figure thus distinguish between the share of housework performed as reported by male and female respondents.

Recently, Korpi et al. (2013) renewed their analysis of family policy with more recent data, including a third dimension, namely support for fathers’ involvement in the care of their young children. Most countries are classified in the same way in this updated version, with Switzerland being the only country that has changed from the traditional family model to the market model. In the present article, Switzerland is classified in the market model in accordance with Korpi et al. (2013).

A random intercept model with a cross-level interaction was used. (Random slopes models were also tested and the results from these did not deviate from the results presented in the article.)

The inclusion or exclusion of control variables does not change the overall results much. The effects of the single control variables are in most cases in line with previous research. See Table 2 for more details.

For reasons of validity, I have also tested other contextual variables measuring more general dimensions of women’s emancipation compared to my policy measures. Among these measures were (1) the Gender-Equality Index which has been created by the UNDP to capture differences in the distribution of achievements between women and men in relation to the labour market, societal empowerment and reproductive health (http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/gii/), and (2) OECD figures concerning the countries’ maternal employment ratio (including women with a child under 15), (OECD Family Database: http://www.oecd.org/els/socialpoliciesanddata/oecdfamilydatabase.htm). As explanatory factors, both these measures perform much worse than the gender-equality norms measure. Among men, the patterns are similar to those of the gender-norms index but the relationships are much weaker, and among women the relationship was close to zero in both cases.

References

Baxter, J. (1997). Gender equality and participation in housework: A cross-national perspective. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 28(3), 220–248.

Baxter, J. (2000). The joys and justice of housework. Sociology, 34(4), 609–631.

Bettio, F., & Plantenga, J. (2004). Comparing care regimes in Europe. Feminist Economics, 10(1), 85–113.

Blair, L. S., & Johnson, M. P. (1992). Wives’ perception of the fairness of the division of household labor: The intersection of housework and ideology. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 570–581.

Braun, M., Lewin-Epstein, N., Stier, H., & Baumgartner, M. K. (2008). Perceived equity in the gendered division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 1145–1156.

Brines, J. (1994). Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labor at home. American Journal of Sociology, 100(3), 652–688.

Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2007). Why welfare states persist: The importance of public opinion in democracies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Daly, M. (2005). Changing family life in Europe: Significance for state and society. European Societies, 7(3), 379–398.

Daly, M., & Rake, K. (2003). Gender and the welfare state: Care, work and welfare in Europe and the USA. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Davis, S. N. (2010). Is justice contextual? Married women’s perceptions of fairness of the division of household labor in 12 nations. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 41(1), 19–39.

Davis, S. N., & Greenstein, T. N. (2004). Cross-national variation in the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1260–1271.

DeMaris, A., & Longmore, M. (1996). Ideology, power, and equity: Testing competing expectations for the perception of fairness in household labor. Social Forces, 74(3), 1043–1071.

Ellingsæter, A. L., & Leira, A. (2006). Politicising parenthood in Scandinavia. Bristol: Polity Press.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The southern model of welfare in social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 6(1), 17–37.

Ferrera, M. (Ed.). (2005). Welfare state reform in southern Europe: Fighting poverty and social exclusion in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece. London: Routledge/EUI studies in the political economy of welfare.

Fuwa, M. (2004). Macro-level gender inequality and the division of household labor in 22 countries. American Sociological Review, 69(6), 751–767.

Gager, C. T. (1998). The role of valued outcomes, justifications, and comparison referents in perceptions of fairness among dual-earner couples. Journal of Family Issues, 19(5), 622–648.

Gager, C. T., & Hohmann-Marriott, B. E. (2006). Distributive justice in the household: A comparison of alternative theoretical models. Marriage and Family Review, 40(2/3), 5–42.

Hellevik, O. (2009). Linear versus logistic regression when the variable is a dichotomy. Quality & Quantity, 43(1), 59–74.

Hook, J. L. (2006). Care in context: Men’s unpaid work in 20 countries, 1965–2003. American Sociological Review, 71(4), 639–660.

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Korpi, W. (2000). Faces of inequality: Gender, class and patterns of inequalities in different types of welfare states. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 7(Summer), 127–191.

Korpi, W., Ferrarrini, T., & Englund, S. (2013). Women’s opportunities under different family policy constellations: Gender, class, and inequality tradeoffs in western countries re-examined. Social Politics, 20(1), 1–40.

Kumlin, S., & Svallfors, S. (2007). Social stratification and political articulation: Why class differences in attitudes differ across countries. In S. Mau & B. Veghte (Eds.), Social justice, legitimacy and the welfare state (pp. 19–46). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Lennon, M. C., & Rosenfield, S. (1994). Relative fairness and the division of housework: The importance of options. American Journal of Sociology, 100(2), 506–531.

Mettler, S., & Soss, J. (2004). The consequences of public policy for democratic citizenship: Bridging policy studies and mass politics. Perspectives on Politics, 2, 55–73.

Mikula, G. (1998). Division of household labor and perceived justice: A growing field of research. Social Justice Research, 11(3), 215–241.

Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82.

Neyer, G. (2006). Family policies and fertility in Europe: Fertility policies at the intersection of gender policies, employment policies and care policies. MPIDR working paper WP 2006 010.

Nilsson, K., & Strandh, M. (2007). The gendered organisation of paid work, housework and voluntary work in Sweden. In I. Crespi (Ed.), Gender mainstreaming and family policy in Europe: Perspective, researches and debates (pp. 199–224). Milano: Eum x sociologia.

Nordenmark, M., & Nyman, C. (2003). Fair or unfair? Perceived fairness of household division of labour and gender equality among women and men: The Swedish case. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 10(2), 181–209.

Orloff, A. (1993). Gender and the social rights of citizenship: The comparative analysis of gender relations and welfare states. American Sociological Review, 58(3), 303–328.

Öun, I. (2012). Conflict and concord in work and family. Family policies and individual’s subjective experiences. Dissertation No. 70, Department of Sociology, Umeå University.

Page, B., & Shapiro, R. (1993). The rational public and democracy. In G. E. Marcus & R. L. Hanson (Eds.), Reconsidering the democratic Public. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Pascall, G., & Lewis, J. (2004). Emerging gender regimes and policies for gender equality in a wider Europe. Journal of Social Policy, 33(3), 373–394.

Robila, M. (2012). Family policies in eastern Europe: A focus on parental leave. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(1), 32–41.

Ruppanner, L. (2008). Fairness and housework: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 39(6), 963–975.

Saxonberg, S., & Sirovatka, T. (2006). Failing family policy in postcommunist central Europe. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 8, 185–202.

Soss, J., & Schram, S. (2007). A public transformed? Welfare reform as policy feedback. American Political Science Review, 101(1), 111–127.

Stier, H., & Lewin-Epstein, N. (2007). Policy effects on the division of housework. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 9(3), 235–259.

Svallfors, S. (2007). Introductory chapter. In S. Svallfors (Ed.), The political sociology of the welfare state: Institutions, social cleavages and orientations (pp. 1–29). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Thévenon, O. (2011). Family policies in the OECD countries: A comparative analysis. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 57–87.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Öun, I. Is it Fair to Share? Perceptions of Fairness in the Division of Housework Among Couples in 22 Countries. Soc Just Res 26, 400–421 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-013-0195-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-013-0195-x