A strained relationship exists between mainstream economics and ethics. Over the last decade, behavioral economists have strongly argued for the importance of fairness in motivating behavior, based on substantial experimental evidence. Two main approaches to the modeling of fairness have been proposed: the outcome-based inequity aversion approach, and the intention-based reciprocity approach. Both approaches have been quite successful in explaining the experimental evidence. Nonetheless, this paper questions the role that is assigned to fairness in these models and the way fairness is incorporated, using recent experimental findings concerning emotions and fairness perceptions. The analysis supports the view that feelings are important for justice, also from a policy perspective, and pleads for closer attention being paid to the functioning of emotional brain systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mainstream economic thinking maintains a strained relationship between ethics and economics. As witnessed by economics textbooks, the predominant view of human behavior and motivation is that of homo economicus. That is, people are assumed to be rational and self-interested, with no moral values. This model of man is used for explaining and predicting economic behavior in the private sector (producers and consumers) as well as the public sector (politicians and bureaucrats). On the other hand, there is welfare economics dealing with aggregate or social welfare, which concerns the inevitable issue of how to evaluate—from a social point of view—the different individual welfare levels emerging from the various economic transactions that people get involved in. In economics this issue is addressed under the heading of equity, as a complement to the issue of efficiency. Roughly put, the latter concept refers to the size of the economic pie (like national income), while the former relates to the distribution of the pie. Because any such social welfare evaluation requires an equity criterion, inevitably moral judgements come in, even if the economist does not take a stance regarding the question whether one criterion is to be preferred over another. Two generally referred to criteria are the (Benthamite) utilitarian criterion, which holds that social welfare equals the sum of the individual welfare levels, and Rawls’ maximin criterion stipulating that the level of social welfare is determined by the welfare level of the least-well-off person. Typically, not much attention is paid to the relevance of these criteria: Whose moral values do they actually refer to, and what role do they play in economic behavior? If homo economicus is assumed to prevail in the private as well as the public sector, who is the agent of equity? Moreover, equity considerations cannot influence the behavior of economic agents who are by assumption amoral.

Economics has not always been like this. Historically, going back at least to Aristotle, this discipline can be seen as an offshoot of ethics. In fact, the ‘founding father’ of economics, Adam Smith, not only wrote The Wealth of Nations but also The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Furthermore, he was a professor of moral philosophy in Glasgow. I will not go into the ‘Adam Smith problem’ concerning the relationship between these two works and the question of whether Smith held a coherent view of human behavior. I only notice that self-interest as a behavioral motive, focused on in The Wealth of Nations, became the dominant view in the development of economics. In his influential study An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science, Lionel Robbins argued that: “it does not seem logically possible to associate the two studies [economics and ethics] in any form but mere juxtaposition.”Footnote 1

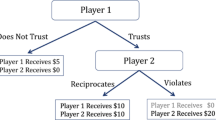

However, life is stronger than doctrine. Although economics seemed extremely successful with its parsimonious homo economicus model, after Robbins’ verdict, gradually more and more empirical (in particular, experimental) evidence has accumulated of behavior deviating from the theoretical predictions. Labelled anomalies, problems appeared with respect to the characteristics of homo economicus, regarding both its assumed rationality and self-interest. Influenced by the seminal studies of Nobel Prize laureates Herbert Simon and Daniel Kahneman (work with the late Amos Tversky), and the results of many other studies, more and more economists started to acknowledge the importance of bounded rationality, as manifested by the limitations and peculiarities of human judgement and reasoning. An abundance of empirical evidence showed man to be liable to all sorts of effects and fallacies (like framing effects and sunk-cost fallacies) and not to be a particularly good statistician.Footnote 2 For this paper, however, a more recent development is even more important. Using the (for economics) new research method of laboratory experimentation, it was discovered over the last two decades that self-interest alone cannot explain the behavioral results from several relatively simple games.Footnote 3 Only by assuming the presence of other-regarding motives, for example, one could explain why people give in a dictator game and reject in an ultimatum game. In a dictator game, a completely anonymous player (the dictator) can decide how much money (from a fixed endowment) to give to another person, while this other person can only accept what is offered. In this game, typically around 20% of the endowment is given away. In the ultimatum game, one player (the proposer) makes a take-it-or-leave-it offer, dividing some amount of money between herself and another person. The other person (the responder) can either accept or reject the offer. If s/he accepts, then the players get the amounts as specified in the offer. In case of rejection, however, both get nothing. In this game responders typically reject small offers of about 20% half the time, even though this is costly to them and the interaction is anonymous and not repeated. (For an excellent survey of these games, see Camerer, 2003.) Interestingly, these findings stimulated in a natural way an interest in equity and fairness related issues.

The felt need to revise the homo economicus model in order to capture the observed behavioral phenomena has led to a new strand of research in economics, indicated as Behavioral Economics, which aims at increasing the realism of the psychological underpinnings of economic analysis. By incorporating robust psychological evidence, the ambition is to arrive at a model of homo sapiens, replacing the simplistic homo economicus model which seems to work well in some (particularly, market) environments but fails more generally. In this paper, attention will be restricted to what behavioral economics has to say about fairness. “Fairness models in economics” discusses the two main theoretical modelling approaches. “Evidence concerning the role of affect and fairness” presents direct experimental evidence concerning the role of affect and fairness. Using these results, in “Fairness models revisited,” it is questioned whether fairness really plays the role assumed in the theoretical models, and to the extent it does, whether the way it is modeled is appropriate.

Fairness models in economics

In a sense, ethics is back in economics. In the previous section we described the procrustean situation in mainstream economics, where ethics is more of an addendum to (welfare) economics, being not well integrated with the maintained view of homo economicus. Behavioral economists have brought the issue back on the table by claiming that equity or fairness plays a major role in the behavior of homo sapiens.Footnote 4 In an influential paper, Fehr and Schmidt (1999, p. 817) write: “By now we have substantial evidence suggesting that fairness motives affect the behavior of many people.” It is not the right place here to go into a detailed discussion of the many experimental and theoretical studies in this research area. For our purpose it suffices to refer to the two main modeling approaches to the incorporation of fairness that have emerged. Central to the one approach is the assumption of outcome-based inequity aversion, while the other hinges on intention-based reciprocity (for a theoretical and empirical survey, see Fehr and Schmidt, 2002). Both approaches assume that fairness involves an equitable payoff.Footnote 5

In inequity aversion models (Bolton and Ockenfels, 2000; Fehr and Schmidt, 1999), which focus on the outcomes or payoffs of social interactions, any deviation between an individual’s payoff and the equitable payoff (e.g., the mean payoff or the opponent’s payoff) is supposed to be negatively valued by that individual. More formally, the crucial difference between an outcome-based inequity aversion model and the homo economicus model is that, in addition to the argument representing the individual’s own payoff, a new argument is inserted in the utility function showing the individual’s inequity aversion (social preferences), as in the social utility model (see, e.g., Handgraaf et al., 2003; Loewenstein et al., 1989; Messick and Sentis, 1985). The individual is then assumed to maximize this adapted utility function.

In intention-based reciprocity models it is not the outcomes of the interaction as such that matter, but the intentions of the players (Rabin, 1993; see also Falk and Fischbacher, 2006). The idea is that people want to reciprocate perceived (un)kindness with (un)kindness, because this increases their utility. Obviously, beliefs play a crucial role here. More formally, in this case, in addition to an individual’s own payoff a new argument is inserted in the utility function incorporating the assumed reciprocity motive. As a consequence, if someone is perceived as being kind it increases the individual’s utility to reciprocate with being kind to this other person. Similarly, if the other is believed to be unkind, the individual is better off by being unkind as well, because this adds to her or his utility. Again, this adapted utility function is assumed to be maximized by the individual.

Note that the two modeling approaches discussed above incorporate fairness by ‘just’ adding an argument in the utility function. Behavior is still assumed to be in line with the rational pursuit of stable preferences, consistent beliefs, and the maximization of utility. In doing so, the life of homo sapiens has in fact become (even) more complicated than that of homo economicus, because the required reasoning, involving now additional (social) preferences or beliefs, is more demanding. This seems to run counter to the other strand of research in behavioral economics focusing on bounded rationality. Nonetheless, these models have been quite successful in providing an explanation for experimental findings concerning a variety of games.Footnote 6 For example, in a quite intuitive way inequity-aversion can explain not only why people give in dictator games, or why they voluntarily contribute to public goods, but also why they reject ‘unfair’ proposals in ultimatum games. Nevertheless, even neglecting the issue of bounded rationality, I think that these fairness models are problematic in two respects. First, is it really fairness that drives behavior in these games? Second, if this is indeed the case, is this the right way of modeling fairness? Or, put differently, can fairness be adequately treated as an issue of rational (reasoned) behavior? The next section presents recent experimental findings concerning a game related to the ultimatum game, which provide some answers to these questions.

Evidence concerning the role of affect and fairness

Although fairness is referred to extensively in the studies mentioned in the previous section, and sometimes emotions are also mentionedFootnote 7 one typically does not directly measure how people feel or what they actually think is fair in a given context. In this section, a series of experiments will be discussed that are exceptional in this respect. They all concern the power-to-take game (Bosman and van Winden, 2002), a game that is related to the ultimatum game but differs from it in a way that is interesting for studying fairness. Like the ultimatum game, the (basic) power-to-take game is a one-shot, two-person, two-stage game, in which a proposer and a responder are randomly and anonymously matched. However, there are three differences with the standard ultimatum game: (1) the proposer and the responder are endowed with an equal amount of money or income (instead of one ‘pie’ to be divided); (2) the proposer can only make a proposal of how to divide the responder’s income (instead of this single pie); (3) the responder can only destroy own income and s/he can do this in any proportion, ranging from 0 to 1 (instead of just accepting or rejecting and thereby destroying the whole pie). Note that the last point means that destruction concerns a fraction of the total income of the responder and not just the part claimed by the proposer.

More formally, let the proposal of the proposer at the first stage of the game be indicated by the take rate ∈[0,1], which is the part of the responder’s income E resp that will be transferred to the proposer after the second stage. At the second stage, the only action that the responder can take is to decide on the destruction rate d ∈[0,1], the part of E resp that will be destroyed. For the proposer the payoff of the game thus equals the transfer t(1−d)E resp, generating a total earnings of: E prop + t(1−d)E resp (where E prop denotes the proposer’s income at the start of the game). For the responder, the payoff equals (1−t)(1−d) E resp, which also determines this player’s total earnings. Note that in the studies to be discussed below the initial income of both the proposer (E prop) and the responder (E resp) is always exactly the same (i.e., E prop = E resp).

The power-to-take game was designed to provide a simple but stark and interesting environment to study the interaction between (naturally induced) emotions and economic behavior. For example, it gives a strong setting for anger and guilt or shame related emotions, because both players start out with the same clearly assigned income and only the income of the responder is at stake. From a fairness point of view the former is important, because it produces an unambiguous and equitable starting point. Moreover, the fact that a responder can destroy any part of his or her own (prior-to-the-take) income gives an opportunity to examine potential trade-offs between punishment and monetary gain. Together, these features seem to make the power-to-take game more expedient for our study than the ultimatum game.

The power-to-take game is also intrinsically interesting because it in essence models situations where one agent can appropriate part of the resources of another agent, while the latter has the opportunity to diminish the room for appropriation by destroying (part of) these very resources. It thereby captures some important aspects of taxation, principal-agent relationships, and monopolistic pricing (see Bosman and van Winden, 2002). To give an example, consider taxation. The proposer can be regarded, in an admittedly simplistic way, as a majority coalition (government) that by means of taxation can claim part of the income of the minority (the responders). The minority can retaliate by destroying part of its income (the tax base). If income refers to the returns on the supply of a production factor, “destruction of income” could stand for a diminished supply of this factor. Incidentally, to the extent that destruction is emotion driven this implies a new source of welfare cost of taxation, labeled emotional hazard by Bosman and van Winden (2002).

We will now first present some typical findings concerning the behavior of proposers and responders in this game. Then, the significance of emotions, focusing initially on responders, is discussed. Finally, the significance of fairness is addressed and linked up with the importance of emotions more generally.

Behavior in the Power-to-Take Game

Before going into the findings related to the topic of this paper—affect and fairness—it is instructive to pay some attention to the behavioral results that are found with the power-to-take game. Remarkably, on average, the behavior of proposers and responders turns out to be quite similar to that found for the ultimatum game.Footnote 8 The mean as well as the median claim (take rate) of the proposer is about 60%, while in the ultimatum game the mean is between 60% and 70% and the median between 50% and 60%. Furthermore, in the power-to-take game responders destroy about 8% of their income when the proposer’s claim is below 60%, whereas 58% is destroyed if the claim exceeds 80%. For the ultimatum game the corresponding figures for destruction are 5% and 50%, respectively. Given the relatedness of the two types of games this similarity in outcomes may not be that surprising, at first glance. Note, however, that in the power-to-take game it is not the total pie but only the responder’s income (endowment) that is at stake. As a fraction of total income, a mean take rate of 60% implies a claim on total income (including the proposer’s income) of 80%, which exceeds substantially the means of the proposers’ claims observed for the ultimatum game. This outcome by itself already implies a problem for the outcome-based fairness models, because it appears that not only outcomes matter.

Evidence of the Significance of Affect

More important for the subject matter of this paper are the following findings concerning the significance of emotions. Although some earlier studies had already suggested that emotions might be responsible for the retaliation or punishment observed in games like the ultimatum game (see, e.g., Pillutla and Murnighan, 1996), economists shied away from investigating this issue head-on. The power-to-take game was developed to give precisely this line of thinking its best test. Because only the responder’s income is at stake, if at all, one would hypothesize that especially in this case emotional reactions should show up. Indeed, substantial support for this hypothesis has been found in a series of studies of this game, using self-reports of experienced emotions.Footnote 9 A consistent and robust observation is that destruction of income is significantly related to the experienced emotions of responders, in particular the negative emotions of anger, irritation, and contempt (for convenience, labelled as ‘anger’ below). Figure 1 illustrates.Footnote 10

A further piece of evidence that emotionality is at stake concerns the time taken for a decision to destroy. As Fig. 2 shows, the most time is taken by the decision to destroy something, that is, between 0% and 100%.Footnote 11 However, note that the decision to destroy everything takes much less time, and about as much as the decision to destroy nothing. This seems hard to explain assuming purely rational decision-making. The argument is that, whatever one decides, one has to arrive at this decision by calculating what is optimal anyway. In this respect, for rational decision-making, 0% or 100% is similar to, say, 30% because all options have to be considered first to determine what is optimal. In contrast, the different decision times can be explained quite intuitively by emotional arousal. Low as well as high arousal may lead to relatively fast decision making. The former because in this game it may be pretty obvious what a rational decision requires, namely, to destroy nothing (remember the anonymity and one-shot character of the game). In case of high arousal the decision time can be short because emotions may take over. If emotional intensity is strong it may surpass a point of no return or regulation threshold (Frijda, 1986), leading to a mode of operation where we just react rather than think; Goleman (1996) speaks of emotional hijacking. It is only when arousal is intermediate that the interplay between emotion and cognition becomes prominent and starts to take time. The way affect precisely interacts with cognition has become a hot topic in decision-making research that goes beyond the scope of this article (see, e.g., Ashby et al., 1999; Forgas, 1995; Lerner and Keltner, 2001; Kruglanski et al., 2000).

Another finding that is natural from an emotions point of view but harder to explain otherwise, is that anger and destruction turn out to be negatively related to the expected take rate, in addition to being positively related to the take rate. If inequity aversion or intentions are important as motivational factors one would expect the actual (observed) take rate but not the expected take rate to be significant. From an emotional arousal point of view, though, unexpectedness is important (Ortony et al., 1988). Figure 3 illustrates the importance for destruction by showing that people who did not destroy were typically ‘pessimists,’ that is, they expected a higher take rate than the one they were confronted with, while ‘optimists’ (who expected a lower take rate) typically destroyed their income.Footnote 12 Note that these responders were asked to indicate the take rate they expected just before they observed the take rate.

All these findings on the role of affect in the power-to-take game were obtained using self-reports of experienced emotions. However, there is also physiological evidence of emotional arousal underlying the decision to destroy in this game (Ben-Shakhar et al., 2004). Interestingly, this further study showed that the physiological measure (skin conductance) and self-reported anger were not only correlated among themselves but also with destruction and expectations in a way confirming the previous findings.Footnote 13

Several of the findings generated by these power-to-take experiments fly in the face of the fairness models discussed in the previous section. This particularly holds for the observed reference point effect and the significant role played by expectations and emotions. Next, it will be shown that the role imputed to fairness is also problematic.

The Role of Fairness and Affect

Although fairness has become a well entrenched concept in behavioral and experimental economics (see, e.g., Camerer et al., 2004), people participating in experiments are surprisingly seldom asked what they themselves think is fair in the context of the experiment.Footnote 14 As will be shown below, this is important because behavior induced by unfairness may also be triggered for other reasons. This raises the issue of whether it is indeed fairness that is at stake in the types of games covered by the fairness models discussed above. To address this issue, in some power-to-take experiments proposers and responders were asked at the end of the experiment what they considered to be the fair take rate (Reuben and van Winden, 2004, 2005).

Focusing first on the responders, it is found that the perceived fair take rate has neither a significant independent impact on the experience of anger nor on the decision to destroy (Reuben and van Winden, 2004). Only the actual and the expected take rate are significant in these respects. Although this result throws doubt on the generally claimed importance of fairness for responders’ behavior in games like this, it may still be the case that fairness plays a more indirect role than is usually envisaged. Suggestive in this respect is the additional finding that the perceived fair take rate functions as a kind of lower bound for the expected take rate. Only in a relative few cases (4.6%) the former exceeds the latter. In other words, the overwhelming majority of responders expected a higher take rate than the one they considered to be fair. Moreover, there is a wide spread in the perception of what is fair. Similarly for proposers the perceived fair take rate appears to function as a lower bound, because the take rate typically exceeds the fair take rate. And, again, there is quite some variance in the perception of what is fair.

However, the fair take rate appears to play a more important role in the decision making of proposers, but remarkably only in combination with the experience of shame. The following results are taken from a repeated power-to-take game, where participants had to play the game twice (Reuben and van Winden, 2005). Proposers who lowered their take rate in the second game (against a new randomly chosen responder) appeared to be in particular those who experienced a high intensity of shame at the end of the first game. Interestingly, the experience of shame turned out to be particularly strong when the chosen take rate exceeded the perceived fair take rate and destruction was observed.Footnote 15 Moreover, although similar effects are found for guilt, the effects are stronger for shame. The fact that the observation of destruction by the responder plays a role is in line with these outcomes, since the disapproval of others plays an important role in shame (Tangney and Dearing, 2002). Figure 4 illustrates. Thus, even though fairness does seem to play a significant role in the decision of the proposers, it appears to be mediated by the experience of emotions, in particular the emotion of shame.

Some recent work on leader-follower effects should be mentioned here, suggesting that adherence to fairness (the equal division rule) is moderated by role assignment. For instance, experimental evidence reported by De Cremer and van Dijk (2005) shows that leaders take more than followers from a common resource, with followers sticking more to the equal division rule. Moreover, this effect can be explained in terms of feelings of entitlement. The way people behave in the role of proposer in the power-to-take game seems consistent with this finding. Although their role was randomly assigned, they may have felt entitled to take more than the equal division rule that would have implied a zero take rate. Note, however, that the anger responders experienced in this game and their destructive behavior were not directly related to what they believed to be a fair take rate. This discrepancy with the behavior of followers in the study of De Cremer and van Dijk may very well be due to the fact that in their study leaders and followers made their decision simultaneously.

Returning to the finding that people show a substantial heterogeneity in their perceptions of fairness, it is further noted that these perceptions seem in addition not very stable, which may explain part of the heterogeneity. In the second game of the experiment discussed above some participants kept the role (of responder or proposer) they had in the first game, whereas others switched roles. It turns out that switching clearly affected their fairness perception (reported at the end of the experiment), as Fig. 5 demonstrates.Footnote 16 This figure clearly shows that having experience with both roles leads to higher fair take rates, with the mode of the distribution shifting from 0% to 50%. Perhaps the experience of role mobility makes one more tolerant, because it fosters the idea that everyone can be in the more advantageous position at some point. In any case, this result suggests that the fairness perceptions are not that stable, contrary to what is assumed in the fairness models in economics.

In the next section, I will revisit these models with a summary of the implications of the experimental findings discussed in this section. Moreover, some new experimental findings will be presented demonstrating the importance of emotions for fairness.

Fairness models revisited

In both of the two main modeling approaches discussed above, fairness is incorporated by adding an argument in the utility function and assuming stable (fairness) preferences, consistent beliefs, and the maximization of utility. Two critical questions were raised after the presentation of the respective models: (1) Is it really fairness that drives behavior in the games these models are applied to? (2) If so, is this the right way of modeling fairness, that is, can fairness be adequately treated as an issue of rational (reasoned) behavior? In my view, the experimental findings discussed in the previous section do not support a positive answer to these questions.

Regarding the first question, fairness does not seem to play a prominent role in the negative reciprocity observed in responder behavior. Only proposers’ behavior seems to be significantly motivated by fairness. Moreover, both responders and proposers show substantial heterogeneity and path dependency in their perception of fairness, which makes it hard to qualify fairness as a shared stable preference.Footnote 17 Concerning the second question, it turns out that not only the behavior of responders may be better explained as an emotional reaction, driven by anger, even the role played by fairness in the behavior of proposers appears to be mediated by emotions, namely by shame and guilt. Consequently, it seems unwarranted to see fairness as just an issue of rational (reasoned) behavior.Footnote 18

I will now shortly discuss two additional pieces of experimental evidence showing the importance of emotions for fairness. Hopfensitz and Reuben (2005) investigate how emotional mechanisms facilitate the enforcement of, and the compliance with, norms. Although there is substantial evidence by now that people are willing to punish others for unkind behavior, even if this is costly to them and there is no chance that they will meet these others again (see, e.g., Camerer, 2003), it is not obvious from these studies what would happen if one allows the punished to punish back. In reality this opportunity typically exists. Using a repeated (sequential) social dilemma game where players are allowed to punish each other in multiple rounds, and measuring emotions via self-reports, they find the following. First of all, punishment leads to retaliation by the punished, where both instances of reciprocity are found to be related to anger. Consequently, a bad sequence of mutual punishment can result, with no increase in cooperative behavior as observed under one-sided punishment. However, it turns out that retaliation by the punished is inhibited if they experience shame (or guilt). Furthermore, it is the combination of feeling shame and being confronted with substantial punishment for unkind behavior, which makes the punished to adapt their behavior. These findings support the view that anger plays an important role in the enforcement of a norm (as related to cooperative or fair behavior), while in addition showing the significance of the social emotions of shame and guilt for making people comply to a norm.

With repeated interaction these emotional responses may have consequences similar to the reputation effects known from dynamic game theory (see, e.g., Camerer, 2003). In a repeated game, a player may be willing to take the costs of punishing in early rounds to build up a reputation of being ‘tough’ (i.e., someone who actually likes to punish), in order to benefit from this reputation in later rounds because it makes the threat to punish credible. Emotions like anger can function in a similar way as a commitment technology (see Frank, 1988). The reason is that emotions and the action tendencies that are involved are difficult to control. The processes underlying emotions are unconscious and are not cognitively penetrable. In this sense, they are involuntary or unbidden, that is, one cannot simply choose an emotion (Frijda, 1986; LeDoux, 1998). Thus, for example, with repeated interaction proposers may come to anticipate the angry response of a responder and find the threat of punishment credible. This would stimulate them to adjust their behavior accordingly, like with reputation effects.

The enforcement of a norm has external effects, because others are affected by the maintenance of the norm. For example, all benefit when members of a community feel urged to behave cooperatively in a social dilemma situation. However, because of this public good aspect of enforcement a free-riding problem may occur, that is, everyone may like to see the norm enforced but no one is willing to do the job. This would be the consequence of a rational cost-benefit calculus, assuming that the impact of an individual is sufficiently small. If, as the experimental findings suggest, enforcement is particularly motivated by the experience of emotions like anger, it is less clear to what extent such a free-riding problem actually exists, because emotional urges can be difficult to control. To investigate this issue, Reuben and van Winden (2004) ran a three-player power-to-take game experiment, with two instead of one responder randomly matched to a proposer (everything else is kept similar). Furthermore, in one of the experimental treatments the responders are strangers to each other, whereas in another treatment they are friends. Emotions concerning the take rate selected by proposers (identical for both responders) as well as regarding the destruction of own income by the other responder are again measured with self-reports. The main new finding is that friends destroy more and are better at coordinating their punishment. Interestingly, it appears that the emotional response towards the other responder facilitates the coordination among friend-responders but not among stranger-responders. Whereas stranger-responders experience stronger negative emotions if they notice that they destroyed more than the other responder than when they destroyed less, emotions are similar for friend-responders in these cases. In addition, and in contrast to stranger-responders, friend-responders get a positive emotional boost if they succeed in coordinating on the same level of punishment. Because of these emotional mechanisms, the situation resembles a coordination game with punishment being the risk-dominant choice for friend-responders, whereas no punishment is the risk-dominant choice for stranger-responders. What makes these results relevant for this paper is that affective ties seem to be important for overcoming the free-riding problem in norm enforcement.

Conclusion

In a sense, ethics is back in economics, as witnessed by the recent upsurge of studies referring to ‘fairness’. Over the last decade, several approaches have been developed to incorporate fairness in models of economic behavior. These models have been fairly successful in explaining behavior in various games that is hard to explain with the standard homo economicus model. This is an important achievement. Nevertheless, the experimental findings presented in this paper point at two problems. First, the concept of fairness is invoked in cases where other (emotional) motives appear to play a more prominent role. For example, it seems that punishment in a game like the power-to-take or ultimatum game is more driven by anger about the appropriation of resources than a concern about fairness. Second, these approaches assume that fairness can be modeled as just another (stable) preference that is rationally taken into account by the individual, which can be represented by an additional argument in the utility function to be maximized. However, the experiments discussed above show that it is probably not so much cognition but emotion that plays a major role in the individual enforcement of, as well as the compliance with, norms like fairness. Unfortunately, it is not so clear yet how to model these emotions. Simply to assume, like in the existing fairness model, that our reasoning (cognition) is calling the shots seems not very promising, however (see LeDoux, 1998). In these models, for example, there is no room reserved for the impact of emotional intensity factors like vividness or for instances like ‘emotional hijacking’ where people simply react without thinking. Emotional brain systems need to be taken seriously, and their functioning requires separate attention (van Winden, 2001).

The evidence presented in this paper supports the view that feelings are important for justice.Footnote 19 Interestingly, in A Theory of Justice Rawls extensively discusses the significance of moral sentiments and a sense of justice in the context of the viability and stability of justice principles. Unfortunately, this part of his influential work has been completely neglected in economics. The reason seems to be the exclusive focus on rational—in the sense of reasoned—decision making, also in matters of justice. According to Kolm (1996, p. 8): “The ethical progress in justice consists in replacing irrational views by rational ones (...), and notably (...) emotion and intuition by reason.” This may be so from a normative philosophical standpoint, but is a seriously deficient view when it comes to policy and the implementation of justice principles. Acknowledging the important role played by emotions in motivating behavior, one needs countervailing emotions and not pure reason to change it, as argued by Spinoza in the fourth part of his Ethics (Spinoza, 1979 [1677]).

Rawls emphasized the importance of moral sentiments for the stability of justice principles. From a theoretical perspective this suggests that moral feelings can bring us back to an equilibrium state of justice, where they are no longer active or needed. I would like to end this paper with two remarks in this context. First of all, the absence of feelings need not necessarily imply fairness, in contrast to what is suggested by the often referred to criterion of “fairness as absence of envy” (see Sen, 1990, p.35). The reason is that feelings adapt to circumstances (relative deprivation), so that non-envy can coexist with gross injustice. Secondly, social norms appear to decay without sanctions. This would imply that there can be no static justice equilibrium, but at best a stationary one characterized by regular transgressions and counteracting sanctions triggered by moral sentiments.

Notes

Quoted in Sen (1990, p. 2).

For example, Conlisk (1996, p. 670) notes: “There is a mountain of experiments in which people: display intransitivity; misunderstand statistical independence; mistake random data for patterned data and vice versa; fail to appreciate law of large number effects; fail to recognize statistical dominance; make errors in updating probabilities on the basis of new information; understate the significance of given sample sizes; fail to understand covariation for even the simplest 2 × 2 contingency tables; make false inferences about causality; ignore relevant information; use irrelevant information (as in sunk cost fallacies); exaggerate the importance of vivid over pallid evidence; exaggerate the importance of fallible predictors; exaggerate the ex ante probability of a random event which has already occurred; display overconfidence in judgment relative to evidence; exaggerate confirming over disconfirming evidence relative to initial beliefs; give answers that are highly sensitive to logically irrelevant changes in questions; do redundant and ambiguous tests to confirm an hypothesis at the expense of decisive tests to disconfirm; make frequent errors in deductive reasoning tasks such as syllogisms; place higher value on an opportunity if an experimenter rigs it to be the ‘status quo’ opportunity; fail to discount the future consistently; fail to adjust repeated choices to accommodate intertemporal connections; and more.”

The public good game, ultimatum game, the dictator game, and the gift-exchange or trust game have been particularly instrumental in this respect (see Fehr and Fischbacher, 2002).

For an important attempt to save homo economicus in matters of justice, see Binmore (1994).

See Fehr and Schmidt (2002). It is beyond the scope of this paper to go into details regarding the explanatory power of these models.

See, e.g., Rabin (1993).

Based on data from the experiment of Reuben and van Winden (2004).

Based on data from the experiment of Reuben and van Winden (2005).

Taken from Reuben and van Winden (2004).

For neural evidence of the role played by emotions in the decision to reject in the ultimatum game, see Sanfey et al. (2003).

Pillutla and Murnighan (1996), investigating responder behavior in an ultimatum game experiment, used responses to some open questions (“How did you react when you received your offer?” and “How do you feel?”) to derive fairness perceptions and feelings of anger. They did not directly ask the participants. Both unfairness perceptions and anger feelings turned out to be related to the rejection of offers, with the latter being more important.

Proposers who increased their take rate typically did so after facing no destruction and the experience of regret.

Based on data from the experiment of Reuben and van Winden (2005).

An additional finding pleading against the fairness models is that responders who destroyed (which might be interpreted as caring for fairness) did not typically select a low take rate when they subsequently got the role of proposer.

In this context, see also Falk et al. (2005).

References

Adams J. S. (1965) Inequity in social exchange. In: Berkowitz L. (ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Vol. 2. Academic Press, New York

Anderson S., Bechara A., Damasio H., Tranel D., Damasio A. R. (1999) Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci 2: 1032–1037

Ashby F., Isen A., Turken U. (1999) A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychol. Rev. 106: 529–550

Ben-Shakhar G., Bornstein G., Hopfensitz A., and van Winden F. (2004). Reciprocity and emotions: arousal, self-reports, and expectations, CREED working paper, University of Amsterdam

Binmore K. (1994) Playing Fair : Game Theory and the Social Contract, Vol. 1. MIT Press, Cambridge Mass

Bolton G., Ockenfels A. (2000) A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 90: 166–193

Bosman R., van Winden F. (2002) Emotional hazard in a power-to-take experiment. Econ. J. 112: 147–169

Bosman R., Sutter M., van Winden F. (2005) The impact of real effort and emotions in the power-to-take game. J. Econ. Psychol. 26: 407–429

Camerer C. (2003) Behavioral Game Theory. Princeton University Press, Princeton,

Camerer C., Loewenstein G., Rabin M. (eds.), (2004) Advances in Behavioral Economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Conlisk J. (1996) Why bounded rationality? J. Econ. Lit. 34: 669–700

De Cremer D., van Dijk E. (2005) When and why leaders put themselves first: Leader behaviour in resource allocations as a function of feeling entitled. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 35: 553–563

Falk A., Fehr E., Fischbacher U. (2005) Driving forces behind informal sanctions. Econometrica 73: 2017–2030

Falk A., and Fischbacher U. (2006) A theory of reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 54: 293–315

Fehr E., Fischbacher U. (2002) Why social preferences matter – the impact of non-selfish motives on competition, cooperation and incentives. Econ. J. 112: 1–33

Fehr E., Schmidt K. (1999) A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Quarterly J. Econ. 114: 817–868

Fehr E., Schmidt K. (2002) Theories of fairness and reciprocity – evidence and economic applications. In: Dewatripont M., Hansen I., Turnovsky S. (eds), Advances in Economics and Econometrics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Forgas J. P. (1995) Mood and judgement: The Affect Infusion Model (AIM). Psychol. Bull. 117: 39–66

Frank R. H. (1988) Passions within Reason. Norton, New York

Frijda N. (1986) The Emotions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Goleman D. (1996) Emotional Intelligence. Bantam, New York

Handgraaf M. J. J., van Dijk E., De Cremer D. (2003) Social utility in ultimatum bargaining. Soc. Justice Res. 16:263–283

Hopfensitz A., and Reuben E. (2005). The importance of emotions for the effectiveness of social punishment, CREED working paper, University of Amsterdam

Kolm S. C. (1996) Modern Theories of Justice. MIT Press, Cambridge Mass

Kruglanski A. W., Thompson E. P., Higgins E. T., Atash M. N., Pierro A., Shah J. Y. (2000) To “do the right thing” or to “just do it”: Locomotion and assessment as distinct self-regulatory imperatives. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 79: 793–815

LeDoux J. (1998) The Emotional Brain. Touchstone, New York

Lerner J., Keltner D. (2001) Fear, anger, and risk. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 81: 146–159

Loewenstein G. F., Thompson L. Bazerman M. H. (1989) Social utility and decision making in interpersonal contexts. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 57: 426–441

Messick D. M., Sentis K. P. (1985) Estimating social and non-social utility functions from ordinal data. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 15: 389–399

Moll J., de Oliveira-Souza R., Eslinger P. J., Bramati I. E., Mourao-Miranda J., Andreiuolo P. A., Pessoa L. (2002) The neural correlates of moral sensitivity: A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of basic and moral emotions. J. Neurosci. 22: 2730–2736

Ortony A., Clore L., Collins A. (1988) The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pillutla M. M., Murnighan J. K. (1996) Unfairness, anger, and spite: emotional rejections of ultimatum offers. Organ. Behav. Human Dec. Proce. 68: 208–224

Rabin M. (1993) Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 83: 1281–1302

Reuben E., and van Winden F. (2004). Reciprocity and emotions when reciprocators know each other, CREED working paper, University of Amsterdam

Reuben E., and van Winden F. (2005). Negative reciprocity and the interaction of emotions and fairness norms, CREED working paper, University of Amsterdam

Sanfey A., Rilling J., Aronson J., Nystrom L., Cohen J. (2003) The neural basis of economic decision making in the ultimatum game. Science 300:1755–1758

Sen A. (1990) On Ethics & Economics. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Spinoza (1979), Ethica, Wereldbibliotheek, Amsterdam (originally published as part of the Opera Posthuma, 1677)

Tangney J. P., Dearing R. L. (2002) Shame and Guilt. Guilford, New York

van Winden F. (2001) Emotional hazard exemplified by taxation-induced anger. Kyklos 54:491–506

Walster E., Walster G. W., Berscheid E. (1978) Equity: Theory and Research. Allyn & Bacon, Boston

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Ernesto Reuben for helpful comments and for figures based on joint research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Winden, F. Affect and Fairness in Economics. Soc Just Res 20, 35–52 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0029-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0029-9