Abstract

The aim of this study is to expand our knowledge about the factors that condition late-life loneliness from a longitudinal perspective. We assess the long-term relationship between education, late-life loneliness and family trajectories in terms of the role of partnership and motherhood, as well as their timing for older women. We set two initial hypotheses: (1) family trajectory has a mediating effect and (2) education has a selection effect. Cross-sectional and retrospective data are drawn from the three waves of the SHARE survey (3rd, 5th and 7th waves), selecting a subsample of women aged 65 and over from 11 European countries (N = 10,615). After distinguishing eight different family trajectories by carrying out a Sequence Analysis, the Karlson-Holm-Breen method is used to assess the mediator effect of family trajectory on the relationship between education and loneliness. Multinomial analysis is used to explore whether the probability of different family trajectories of older European women is defined by their level of education. Our results show that education has a selection effect on family trajectories: a higher educational level increases the probability of a non-standardised family trajectory. Significant results of the mediator effect of family trajectory are however only observed for women with medium-level education, as being single and childless at older ages increases the probability of loneliness among these women. Adopting a life-course perspective has permitted us to introduce the longitudinal dimensions of life events, education and family trajectories to the study of feelings of loneliness among women in old age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Loneliness refers to a subjective experience in which individuals feel a lack in the quality or quantity of social relations in terms of support, intimacy or companionship (Cornwell & Waite, 2009; De Jong Gierveld et al., 2018). Loneliness has become central in gerontological studies given that it joepardises the physical and mental health of older adults, as well as their quality of life in a broader sense (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Lara et al., 2019; Puga González et al., 2021). Understanding the factors that condition the feelings of loneliness among older people is of great importance as it presents a unique opportunity to improve the well-being in old age.

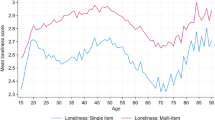

Previous research has evidenced that individual factors as demographic and health-related characteristics are associated to the feelings of loneliness in old age. Most studies indicate that loneliness increases with age and is more common among older women compared to older men (Dahlberg et al., 2015; Fokkema et al., 2012; Vozikaki et al., 2018). Even so, some studies showed that the middle-aged people report more loneliness than older people and older men report more loneliness than older women (Barreto et al., 2021), or no gender differences in loneliness across lifespan (Maes et al., 2019). The variability of the findings has to do with gender or age per se are not key predictors of loneliness, but they are other correlated factors as health status, which worsen with age, or the socioeconomic profile, which differs by gender (Dahlberg et al., 2015). For instance, physical and mental problems are related to an increased probability to experience loneliness in old age. Low mobility functioning is strongly related to late-life loneliness when it hinders social engagement, as well as to present depressive symptoms, increased feelings of uselessness, increased feelings of nervousness and increased feelings of low mood led to a higher likelihood to feel lonely in old age (Aartsen & Jylhä, 2011; Honigh-de Vlaming et al., 2014).

Among all the individual factors related to late-life loneliness, education has normally been considered as a control variable to approach the individual’s socioeconomic status (De Jong Gierveld et al., 2018). The findings in this respect are clear: feelings of loneliness are prevalent among older adults with a low level of education (Dahlberg et al., 2018; Hansen & Slagsvold, 2016; Savikko et al., 2005) whereas individuals with higher educational levels are at lower risk of feeling late-life loneliness (Smith & Victor, 2019). These associations, moreover, have been observed across countries (Sundström et al., 2009).

However, even though the protective effect of higher education against late-life loneliness is well-established, very little is known about the mechanisms behind this. To understand how education influences late-life loneliness, it is necessary to adopt a longitudinal view departing from the fact that individuals almost invariably achieve their higher educational degree at earlier stages of their life course, long before late-life loneliness is experienced. According to the concept of interdependency developed in life course research (Bernardi et al., 2019; Elder, 1985) links are established between different life domains, trajectories over time, and in relation to others. This means that the events experienced, roles played, and decisions made in one life domain are likely to influence biographical development in other life domains and trajectories. It could then be expected that during the time lapse between the achievement of a higher education degree and the point at which late-life loneliness is experienced, other life trajectories intervene in this relationship. In this sense, education and family are intimately related within biographical trajectories, given that the former affects the decisions and timing of family formation (Lappegård & Rønsen, 2005). In turn, the occurrence and timing of family transitions, mainly entering into partnerships and parenthood, have been identified as key determinants of late-life loneliness; especially individuals who have never been married and those who are childless are more prone to experience feelings of loneliness in old age (Dahlberg et al., 2018; Van den Broek et al., 2019), as are those who have not experienced partnership or parenthood ‘on time’ according to the social calendar (Zoutewelle-Terovan & Liefbroer, 2017). In addition, the combination of ‘success’ in different life spheres by way of adapting the biographical path established by the social calendar protects against loneliness. For instance, well-educated individuals who state that they are in a satisfactory marital relationship–which could be considered an indicator of ‘success’ in educational and family trajectories according to sociocultural expectations–experience a stronger protective effect of higher education against late-life loneliness (Hawkley et al., 2008).

Consequently, a paradox arises: individuals with a higher level of education are less likely to experience late-life loneliness, but also more likely to go through non-normative family trajectories, which in turn are associated with higher levels of late-life loneliness. This raises the question of whether the protective effect of education on late-life loneliness could be mediated by family trajectories after completing one’s education, or whether this can be attributed to a selection effect.

1.1 Aims of the Study

While the body of literature on loneliness is rapidly growing, it has been stressed that we need longitudinal approaches to examine the effects that early life experiences have on late-life loneliness (Courtin & Knapp, 2017; Dahlberg et al., 2018; Zoutewelle-Terovan & Liefbroer, 2017). Following this direction, the aim of this study is to deepen our knowledge about how older adults’ biographical trajectories condition their feelings of loneliness. We aim to examine how the interplay of education and family trajectory, two factors that are experienced at distinct stages within the individual life course, may result in different outcomes when it comes to feelings of loneliness among older women in Europe.

Our study focuses on older European women because education conditions the occurrence and timing of family events especially for women (Liefbroer & Corijn, 1999). The probability of highly educated women to follow a non-standardised family trajectory, including marital disruption, having children at older ages or being childless, is higher (Keizer et al., 2008). Furthermore, cohorts of older women in Europe have followed rather standardised family paths across time and space, characterised by coupled transitions out of the parental home into marriage and motherhood (Van Winkle, 2018). Therefore, the effects of the interplay between education and family trajectory on late-life loneliness could be intensified for those who did not get married, did not have children or did not make these transitions ‘on time’ according to the social calendar.

The results of this study provide insights into the ways in which life experiences and life spheres interplay. In addition, the results expand our knowledge about the relations between education, family trajectories and loneliness, allowing to consider the longitudinal effect of the factors influencing loneliness in old age.

1.2 Hypotheses

Taking into account that (1) higher educated individuals show a higher probability of having gone through non-normative family paths and that (2) individuals with non-standardised family trajectories (i.e. no entry or delayed entry to partnership/parenthood) present higher levels of late-life loneliness, we would like to test two nested hypotheses regarding the type of relationship between education, family trajectories and late-life loneliness:

H1

As the educational trajectory usually is developed before the family trajectory, we expect that the family trajectory mediates the relation between education and loneliness for older women. We initially state that the already known relationship between education and loneliness may be mediated by the effect of family trajectories (such as non-standardised family trajectories reducing the positive effect of higher education on loneliness in). For this purpose, we performed a mediation analysis to quantify what part of the effect of educaion on loneliness can be attributed to family trajectories.

H2

Education has normally been considered a distal factor, which means that it does not only directly cause loneliness but also affects the proximate and predisposing conditions for social contacts by determining the availability of personal and material resources (Heylen, 2010). Instead of this mediating effect, education then exerts a selection effect over family trajectories. This would therefore point to an accumulative explanation for the association between late-life loneliness and education and family trajectories from a life course perspective. To test this hypothesis, we calculated the different probabilities of having carried out each of the observed family trajectories according to women’s education Fig. 1.

2 Research Design

2.1 Data Source

Data are drawn from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE is a panel survey representative of the non-institutionalised population aged 50 and over living in Europe. It collects information about multiple aspects of the older European population: demographics, work, family, health, housing etc. (Börsch-Supan, 2013). To carry out the analysis, we utilised three different waves of SHARE: the 3rd (conducted in 2009) and 7th waves (conducted in 2017) known as SHARELIFE, which provide the retrospective information about the past marital and fertility biographies of the respondents, allowing to reconstruct their family trajectories; and the 5th wave (fieldwork conducted in 2013), which registers the respondents’ feelings of loneliness at the time of the interview. Although SHARELIFE was implemented in 14 European countries only ten of these countries took part in the three waves utilised in our analysis (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland).

From the original sample of the 5th wave, we selected a subsample composed of non-institutionalised women aged 65 and over at the time of the survey (N = 16,218) living in some in the ten countries participating in the three selected waves of SHARE. Taking this subsample as a reference, we linked it with the information about family trajectories in the 3rd wave of SHARE. For those who did not participate in the 3rd wave, we used the information from the 7th wave (the 7th wave only compiles biographic information for respondents who did not participate in the 3rd wave). We analysed only information about family trajectories over a specific age range (18–59) for women who were aged 65 and over in 2013 (5th wave). As the 3rd wave of SHARE was conducted in 2009, the age range for the sample was set at 18–59 years old and over in order to capture information about the family trajectories of the women who were aged 65 and over in 5th wave.

After linking the information, the final sample was composed of 9748 older women, with complete information for all variables for 9578 of them. The difference in numbers was due to changes in the countries’ sample sizes and attrition (the wave-to-wave retention rate average from the 3rd to the 7th wave was 73% with similar country specific values; Bergman et al. 2017) as well as, to a lower extent, mortality of participants over the follow-up period. The relative percentage of each country in the final working sample was fairly stable, ranging from 6.9% (Switzerland) to 12.9% (Spain), with eight countries with a percentage equal or higher than 9%. This ensured balanced results in terms of the relative contribution of each country in the analysis.

2.2 Variables of Interest

2.2.1 Loneliness

Loneliness is approached using the Three-Item Loneliness Scale implemented by SHARE. This scale is a short version of the R-UCLA Loneliness Scale, which consists of a 20-item scale to measure feelings of emotional loneliness and social isolation. The Three-Item Loneliness Scale was designed to approach loneliness in questionnaires administered by telephone and has been confirmed to have satisfactory reliability and both concurrent and discriminant validity (Hughes et al., 2004). The three questions included in the scale are: How much of the time do you feel a lack of companionship? How much of the time do you feel left out? How much of the time do you feel isolated from others? The possible answers to these three questions were: often, some of the time, hardly ever/never. The addition of the answers to the three questions forms a scale, with a value of 0.72 in the alpha coefficient of reliability, that ranges from three (not feeling lonely at all) to nine (the highest level of loneliness). Previous research has confirmed that the distribution of values for these variables is not normal, which is why we decided to create a binary dependent variable following the operationalisation proposed by Niedzwiedz et al. (2016). Niedzwiedz et al.’s operationalisation proposes to dichotomise the variable by using the country-specific quartiles of the original variable as a reference in order to account for possible country differences in the cultural conceptualisation of loneliness. The final variable distinguishes between those in the fourth quartile who felt lonely (= 1) and the other three quartiles who did not feel lonely (= 0).

2.2.2 Family Trajectories

The family trajectories of older women aged 65 and over in the 5th wave of SHARE were reconstructed using the retrospective data in SHARELIFE (3rd and 7th waves). Information about family trajectories for women who were not in the 3rd wave of SHARE was taken from the 7th wave when possible.

The family trajectories consider two types of information: marital status (single, cohabiting, married, separated or divorced, widowed) at each age over their life course, and having children or not at every single age. We distinguish between marriage and cohabitation to account for the fact that non-normative family transitions (such as cohabitation in the case of older cohorts) are more exposed to loneliness in old age (Zoutewelle-Terovan & Liefbroer, 2017). In addition, we did not identify the beginning of a new union after separation or divorce because previous research has shown that remarried divorcees are more likely to report feeling lonely than their counterparts in their first marriage. (Van Tilburg et al., 2014).

2.2.3 Education

The information about educational attainment comes from the 5th wave and was coded using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 1997 scale, which was designed by UNESCO to uniform the education statistics to facilitate cross-country comparisons. The original values were grouped as follows: low (corresponding to ISCED 0–2, lower secondary education or lower), medium (ISCED 3–4, higher secondary education) and high (ISCED 5–6, post-secondary education).

2.2.4 Control Variables

All the multivariate analyses were controlled for: age, in order to consider the likely age effect of loneliness; country, to account for possible country differences in family trajectories; and current health status, measured by the Global Activity Limitation Indicator (GALI; limited or not limited), in order to account for the proved influence of health limitations on loneliness (Luo et al., 2012).

2.3 Analytical Strategy

We first adopted Sequence Analysis (Aisenbrey & Fasang, 2010) to reconstruct and describe life-course family trajectories between ages 18 and 59. This method permits to define life-courses as sequences of events allowing to simultaneously account for timing, quantum and ordering of individuals’ experiences. The second step was to generate a typology of family trajectories by calculating the (dis)similarities between family trajectories using Optimal Matching Analysis (OMA; Sankoff & Kruskal, 1983), which makes it possible to group older women into different clusters according to the characteristics of their family trajectories. The similarity between two sequences is determined by calculating the total ‘costs’ of turning one sequence into another: the higher the difference, the higher the cost to make both sequences equal. Substitution costs are empirically defined as the inverse of the transition rates, so more common transitions between two states imply a lower substitution cost (Aassve et al., 2007). This operation provides a matrix of distances, to which we applied a hierarchical Cluster Analysis (CA) using Ward’s minimum variance criterion to obtain clusters of family trajectories (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 2009).

The second step was to explore whether the observed family trajectories mediate the relation between the educational attainment of older women and their feelings of loneliness by using a logistic regression model known as the Karlson-Holm-Breen method (KHB method; Karlson et al., 2012). This method permits to decompose the total effect of a variable into direct and indirect effects in nonlinear probability models by comparing the estimates from two logistic regression models. In the first model, the dependent variable is regressed on a certain variable of interest (education in our case) and control variables, but not the mediators (unadjusted; see coefficients in Table 4). In the second model, we add the mediators (family trajectory) to the list of independent variables (adjusted; see coefficients in Table 5). The KHB method allows for the calculation of which part of the effects of educational attainment on late-life loneliness is moderated by the family trajectories (indirect effect). The effect of education that is left after adjusting for family trajectory is the direct effect and corresponds to the estimates of the adjusted model. Finally, the total effect is the addition of the direct and indirect effects and corresponds to the coefficient of the unadjusted model. In that way, the KHB method makes it possible to test our first hypothesis.

The third step of our analysis was to assess the possible selection effect of education into the observed family trajectories as well as the direct effect of both variables on loneliness (Hypothesis 2). This makes it possible to understand which paths lead to the different family trajectories, i.e. whether education exerts its effect in an early stage in life course. To check whether the different levels of education show higher probabilities of leading to particular family trajectories, we ran a multinomial logistic regression model where the information about family trajectories was our dependent variable and education our variable of interest. We then tested the possible direct effect of these variables on female late-life loneliness by a logistic regression in which both variables are covariates, controlling for the same variables as in the KHB model. This model coincides with the adjusted model in the KHB analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Findings

3.1.1 A Typology of Family Trajectories of Older Women in Europe

The outcomes of the cluster analysis pointed to eight meaningful patterns of family trajectories displayed by older European women (Figure A1 shows the resulting dendrogram). Clusters 1 and 2 (see Fig. 2) present the most frequent family trajectories, characterised by being married and having children but with different timings: in Cluster 1, all women had their first child at age 27 or younger, whereas the women in Cluster 2 were around 40 at the time.

Clusters 3 and 4 include the most heterogeneous patterns of family trajectories, with women who either got divorced or had children within cohabitation (Cluster 3) or experienced a union dissolution at younger ages (Cluster 4). Cluster 5 is also formed by women who cohabitate with their partner over their life course but remained childless.

Cluster 6 is composed of women who were still single and childless by the age of 59. Cluster 7 groups all women who were widowed at early ages (younger than 50). Finally, Cluster 8 is composed of single mothers (women who had children without being in a partnership).

3.1.2 Working Sample Profile

Table 1 displays the number of women in our final working sample sorted by education and family trajectory as well as the prevalence of loneliness in each group. In terms of education, European women aged 65 and over show lower percentages of loneliness when their educational attainment is medium or high when compared with their low-educated counterparts. Regarding family trajectory, clusters characterised by a union dissolution or by being childless (Clusters 3–6) show a higher prevalence of loneliness, but with differences in magnitude depending on educational level. On the other hand, trajectories of long unions (Clusters 1 and 2) and of those who have children without a partner at the time of the survey (Clusters 7 and 8) display a lower prevalence of feeling lonely.

3.2 Multivariate Results

3.2.1 Hypothesis 1 : Family Trajectory as Mediator of the Effect of Education on Late Life Loneliness

Table 2 presents the results for the KHB models assessing whether the family trajectory has a mediating effect on the relationship between education and loneliness. The total and direct effects confirm that education is significantly associated with feelings of loneliness in old age. Results indicate that, compared to low-educated women, older women with a medium or high education are less likely to feel lonely.

Nonetheless, the results for the indirect effect show that only the relationship between medium-level education and loneliness is captured by some of the analysed family trajectories, with an overall positive and significant coefficient for the indirect effect. This reveals a weak mediating effect (0.015) of family trajectory in the relation between education and loneliness. Overall, family trajectory increases the probability of loneliness among medium-educated older women. Concretely, this mediating effect is mainly observed among older women who remained single and childless (Cl. 6) during the observed period (a positive contribution to the indirect effect of 61.8%), with family clusters 3 and 5 showing a lower mediating effect (a contribution of 22.5% and 17.3% respectively). All the other typologies of family trajectories have a negligible contribution to the indirect effect performed by the overall variable.

3.2.2 Hypothesis 2 : The Selection Effect of Education on Family Trajectories

Table 3 displays the predicted probabilities and their confidence interval from the multinomial regression model to assess the association between education and family trajectories. Rather than showing the coefficients from the model (which can be seen in Table 6), the predicted probabilities are presented here in order to make the results easier to interpret. The results confirm the association between educational attainment achieved at early life stages and family trajectories developed at different ages. Medium and highly educated women display higher probabilities of having gone through alternative family trajectories compared to the most prevalent one (i.e. married with children at young ages, the reference category in the model), as can be seen in the family trajectories of Clusters 2, 5 and 6. On the other hand, women with higher education show lower probabilities of being in Cluster 7 (widowed with children).

Table A2, which corresponds to the adjusted model in the KHB analysis (and which explains why the coefficients for education are exactly the same as the direct effects displayed in Table 2), confirms the significant results for the direct association between our two variables of interest (education and family trajectory) and late-life loneliness among women. In addition, we observe that women in family trajectories with union interruptions and without children (Clusters 3–6) present a higher probability of stating that they have feelings of loneliness than those in the most frequent family trajectory (Cluster 1).

4 Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study that analyses the factors associated with late-life loneliness examining interdependencies between life spheres. Our aim was to use a longitudinal perspective to explore how educational level and family trajectory, which are experienced at distinct life stages within the individual life course, interplay to capture an image of loneliness among older women in Europe. Although research has repeatedly shown that higher education protects against late-life loneliness (Smith & Victor, 2019), the reasons for this association have remained unexplored. We set two initial hypotheses to explain the long-term relation between education and late-life loneliness: (1) that family trajectory mediates the relationship between education and late-life loneliness (Zoutewelle-Terovan & Liefbroer, 2017) and (2) that there is a selection effect of education for the type of family trajectory, which subsequently influences loneliness in old age.

As expected, our descriptive results are in line with previous research. Older female cohorts in Europe show highly standardised family trajectories, characterised by lifetime marriage and motherhood. Only a minority are single, separated/divorced, single mothers, childless or widowed at early ages. This homogeneity of family paths among the women born over the first half of the twentieth century is explained by the socio-historical context in which they grew up and made their transitions into adulthood. The materialist values related to economic security and social prosperity consolidated during this period in Europe meant that, for the majority, marriage was the first step to leave the parental home, followed by immediate motherhood (Mayer, 2004).

Our first hypothesis was only confirmed for a very specific female subpopulation: family trajectory mediates the interplay between education and late-life loneliness, but only for the medium-educated older women who were not in a union and remained childless. The older women who present this non-standardised family trajectory showed a significantly lower probability of stating they feel lonely when they have received post-secondary education compared to those with lower levels of education. It is likely that the single childless trajectory of highly educated women resulted from prioritising other personal projects as their professional careers over family formation. In some cases, a wider diversity of roles played across the lifespan have given to them more opportunities to expand their social relations beyond the family, compensating for the negative effect of not having had a partner and/or a child. Also, desires and expectations regarding social relations transcend the family domain for these older women.

Regarding our second hypothesis, it is confirmed that educational attainment exerts a selection effect on the family trajectory. As the educational level increases, so do the probabilities of having entered a family trajectory different from the prevalent family formation pattern characterised by being married with children, regardless of the timing of such transitions. In turn, family trajectory has a significant association with late-life loneliness: older women who were married and had children showed lower probabilities of late-life loneliness (Zoutewelle-Terovan & Liefbroer, 2017), while older childless women and those who have lost their partner present considerably higher probabilities to feel lonely in old age. The results showed that entering into a partnership or motherhood ‘off time’ seems to be less relevant for late-life loneliness than remaining single and childless. These results have showed that the role of education as a distal factor for late-life loneliness not only determines the availability of personal and material resources in old age, as cross-sectional studies have documented so far, but also affects the proximate and predisposing conditions for social contacts across the life span. Our results thus shed light onto how events such as educational attainment and family formation at different individual life course stages interplay to impact on the levels of loneliness in old age among women. Our second hypothesis seems to better capture the paths in which education and family trajectory are associated with late-life loneliness for women. However, despite the influence of education on previous stages of the individual’s life course, the impact of family trajectories on loneliness at older ages persists regardless of individual educational level.

The following limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the second hypothesis was confirmed after a stepwise analysis, whereas the first hypothesis was evaluated applying a unique analysis. However, we performed a robustness check analysis (available upon request) in order to test whether the real effect of education and family trajectory on late-life loneliness of European women was driven by an interaction effect between both variables; the results discarded the significance of this interaction, pointing to the selection effect of education indicated in the second hypothesis.

Second, as mentioned in the methods section, the level of attrition is increased by the fact that the timing of the 5th wave of SHARE collecting biographical information differs from the two other waves by four years. The selection effect that this has on our data is impossible to check. Third, we must keep in mind that these conclusions fit only for a specific cohort of European women who presented a low variability in terms of family trajectories. This, for instance, is the main reason why the sample size of Clusters 7 and 8 (early widowed mothers and single mothers) is relatively small. However, we opted for preserving the distinction between these two types of family trajectory because of their relevant conceptual difference. However, we do not know whether the result would be the same for younger female cohorts for whom cohabitation, separation/divorce or multiple partnerships are more frequent. Income in relation to work domain should be considered in future research as an attribute that conditions the relationship between family trajectories and loneliness in old age. Previous research has pointed to the level of education being especially relevant in relation to the work-life sphere (Dahlberg et al., 2018; Savikko et al., 2005). It could be assumed that the risk of suffering from loneliness decreases as the educational level increases. However, comparative studies with younger women should be carried out to assess how the link between family formation patterns and loneliness in old age is evolving, given the changes in socio-historical contexts.

One direction for future research is to examine how cross-country differences affect the interplay between education, family trajectory and loneliness in old age. We cannot forget that the historical and sociocultural circumstances, and their evolution, are crucial to understand individual’s life choices. In Western Europe, the generations from 1900 to 1945 were born and socialised in two different historical life-course regimes; the Industrial Life-course Regime (1900–1955) characterised by schooling compulsory but only until relative short age and delayed family formation, and the Fordist-Welfare State Regime (1955–1973), characterised by the expansion of secondary and tertiary education, as well as the gender division of labour within nuclear family. However, as Möhring (2016) noticed, the cross-national variation in long term developments (economic, political, social, etc.) influence the way in which these life-course regimes shape the social calendar in each country. Cross-country comparisons are also necessary due to the feeling of loneliness is perceived and defined according to cultural norms and values. So far, the findings in this respect are not conclusive: while most of studies showed that European older people in individualistic (vs. collectivist) countries reported more loneliness (Dysktra, 2009; Barrera et al., 2021), there are also insights of the opposite (Lykes & Kemmelmeier, 2014). In addition, the situation of older men also needs to be explored considering previous evidence of a lower relevance of family as a social determinant of self-perceived health as compared to women (Gumà et al., 2019).

Adopting a life-course perspective will contribute to a deeper understanding of the longitudinal effect of the factors that condition feelings of loneliness in old age, at least, in two main ways. Firstly, it permits to conceptualise late-life loneliness as result of a combination of long-life experiences shaped by the interdependence among life domains and trajectories. Secondly, this perspective allows to consider some characteristics of human biographies that are difficult to measure and operationalise as normativity. In a context of progressive de-standardisation of the life course, to examine this issue will help to obtain a more realistic picture about how to achieve positive and satisfactory ageing.

Availability of Data and Material

Available upon request to the authors.

References

Aartsen, M., & Jylhä, M. (2011). Onset of loneliness in older adults: Results of a 28 year prospective study. European Journal of Ageing, 8, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0175-7

Aassve, A., Billari, F. C., & Piccarreta, R. (2007). Strings of Adulthood: A sequence analysis of young british women’s work-family trajectories. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 23(3), 369–388.

Aisenbrey, S., & Fasang, A. E. (2010). New life for old ideas: The “Second Wave” of sequence analysis bringing the “course” back into the life course. Sociological Methods & Research, 38(3), 420–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124109357532

Barreto, M., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2021). Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, 110066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110066

Bergmann, M., Kneip, T., De Luca, G., & Scherpenzeel, A. (2017). Survey participation in the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE), Wave 1–6. Munich: Munich Center for the Economics of Aging.

Bernardi, L., Huinink, J., & Settersten, R. A. (2019). The life course cube: A tool for studying lives. Advances in Life Course Research, 41, 100258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.11.004

Börsch-Supan, A. (2013). SHARE wave four: New countries, new content, new legal and finantial framework. In F. Malter, & A. Börsch-Supan. (Eds.), SHARE wave 4: Innovations & Methodology (pp. 5–10). Munich: MEA, Max Plank Institute for Social Law & Social Policy.

Cornwell, E. Y., & Waite, L. J. (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000103

Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12311

Dahlberg, L., Andersson, L., McKee, K. J., & Lennartsson, C. (2015). Predictors of loneliness among older women and men in Sweden: A national longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health, 19(5), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.944091

Dahlberg, L., Agahi, N., & Lennartsson, C. (2018). Lonelier than ever? Loneliness of older people over two decades. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 75, 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2017.11.004

De Jong Gierveld, J., Tilburg, T. G. V., & Dykstra, P. A. (2018). New ways of theorizing and conducting research in the field of loneliness and social isolation. In A. L. Vangelisti, & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships (2 ed., pp. 391–404, Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dykstra, P. A. (2009). Older adult loneliness: Myths and realities. European Journal of Ageing, 6(2), 91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-009-0110-3

Elder, G. H. (1985). Life course dynamics: Trajectories and transitions, 1968–1980. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Fokkema, T., De Jong Gierveld, J., & Dykstra, P. A. (2012). Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. Australian Journal of Psycholgy, 146(1–2), 201–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.631612

Gumà, J., Solé-Auró, A., & Arpino, B. (2019). Examining social determinants of health: The role of education, household arrangements and country groups by gender. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 699–708. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7054-0

Hansen, T., & Slagsvold, B. (2016). Late-life loneliness in 11 European countries: Results from the Generations and Gender Survey. Social Indicators Research, 129(1), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1111-6

Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 63(6), S375–S384. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.6.S375

Heylen, L. (2010). The older, the lonelier? Risk factors for social loneliness in old age. Ageing and Society, 30(7), 1177–1196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10000292

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Honigh-de Vlaming, R., Haveman-Nies, A., Bos-Oude Groeniger, I., de Groot, L., & van Veer, P. (2014). Determinants of trends in loneliness among Dutch older people over the period 2005–2010. Journal of Aging and Health, 26(3), 422–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264313518066

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

Karlson, K. B., Holm, A., & Breen, R. (2012). Comparing regression coefficients between same-sample nested models using logit and probit: A new method. Sociological Methodology, 42(1), 286–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081175012444861

Kaufman, L., & Rousseeuw, P. J. (2009). Finding groups in data: an introduction to cluster analysis. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Keizer, R., Dykstra, P. A., & Jansen, M. D. (2008). Pathways into childlessness: Evidence of gendered life course dynamics. Journal of Biosocial Science, 40(6), 863–878. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932007002660

Lappegård, T., & Rønsen, M. (2005). The multifaceted impact of education on entry into motherhood. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 21(1), 31–49.

Lara, E., Caballero, F. F., Rico-Uribe, L. A., Olaya, B., Haro, J. M., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., et al. (2019). Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(11), 1613–1622. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5174

Liefbroer, A. C., & Corijn, M. (1999). Who, what, where, and when? Specifying the impact of educational attainment and labour force participation on family formation. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne De Démographie, 15(1), 45–75. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006137104191

Luo, Y., Hawkley, L. C., Waite, L. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 74(6), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.028

Lykes, V. A., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2014). What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(3), 468–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113509881

Maes, M., Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Van den Noortgate, W., & Goossens, L. (2019). Gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan: A meta–analysis. European Journal of Personality, 33(6), 642–654. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2220

Mayer, K. U. (2004). Whose lives? How history, societies, and institutions define and shape life courses. Research in Human Development, 1(3), 161–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427617rhd0103_3

Möhring, K. (2016). Life course regimes in Europe: Individual employment histories in comparative and historical perspective. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(2), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928716633046

Niedzwiedz, C. L., Richardson, E. A., Tunstall, H., Shortt, N. K., Mitchell, R. J., & Pearce, J. R. (2016). The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: Is social participation protective? Preventive Medicine, 91, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.016

Puga González, D., Fernández-Carro, C., & Fernández Abascal, H. (2021). Multimorbidity, social networks and health-related wellbeing at the end of the life course. In G. Fernández-Mayoralas, y Rojo Pérez, F. (Eds.) Active Ageing and Quality of Life: From Concepts to Applications (pp. 609–628). The Netherlands: Springer.

Sankoff, D., & Kruskal, J. B. (1983). Time warps, string edits, and macromolecules: The theory and practice of sequence comparison. Reading: Addison–Wesley Publication.

Savikko, N., Routasalo, P., Tilvis, R. S., Strandberg, T. E., & Pitkälä, K. H. (2005). Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 41(3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2005.03.002

Smith, K. J., & Victor, C. (2019). Typologies of loneliness, living alone and social isolation, and their associations with physical and mental health. Ageing and Society, 39(8), 1709–1730. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000132

Sundström, G., Fransson, E., Malmberg, B., & Davey, A. (2009). Loneliness among older Europeans. European Journal of Ageing, 6(4), 267.

Van den Broek, T., Tosi, M., & Grundy, E. (2019). Offspring and later–life loneliness in Eastern and Western Europe. ZfF–Zeitschrift für Familienforschung/Journal of Family Research, 31(2), 199–215, Doi: https://doi.org/10.3224/zff.v31i2.05.

Van Winkle, Z. (2018). Family trajectories across time and space: Increasing complexity in family life courses in Europe? [journal article]. Demography, 55(1), 135–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0628-5

Van Tilburg, T. G., Aartsen, M. J., & van der Pas, S. (2014). Loneliness after divorce: A cohort comparison among Dutch young-old adults. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu086

Vozikaki, M., Papadaki, A., Linardakis, M., & Philalithis, A. (2018). Loneliness among older European adults: Results from the survey of health, aging and retirement in Europe. Journal of Public Health, 26(6), 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-018-0916-6

Zoutewelle-Terovan, M., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2017). Swimming against the stream: Non-normative family transitions and loneliness in later life across 12 nations. The Gerontologist, 58(6), 1096–1108. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx184

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 3, 5 and 7 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w3.700, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.700, and 10.6103/SHARE.w7.700), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: N°227822, SHARE M4: N°261982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and University/Spanish Agency of Research. Project “Prevention is better than cure when ageing is behind the door: interplay between social determinants of health in Spain (INTERSOC-HEALTH)” (RTI2018-099875-J-I00 -MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE- PI: Jordi Gumà) FEDER/Spanish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors, C. Fernández-Carro and J. Gumà have contributed equally to plan the study, to develop the statistical analysis and to write the paper. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig.

3.

See Tables

4,

5 and

6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández-Carro, C., Gumà Lao, J. A Life-Course Approach to the Relationship Between Education, Family Trajectory and Late-Life Loneliness Among Older Women in Europe. Soc Indic Res 162, 1345–1363 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02885-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02885-x