Abstract

Various studies have proposed social enterprise as a potential policy intervention and a policy alternative to deal with the complex problem of wellbeing enhancement. However, the relationship between social enterprise and wellbeing has not been fully expounded, particularly its impact on the local community. This study aims to empirically examine the relationship between social enterprise and the wellbeing of individuals in the local community, utilizing a multilevel framework. It further explores whether social capital, measured as trust, network, and participation, plays a moderating role in the relationship between local social enterprise and the wellbeing of individuals in the community. The results indicate that social enterprise has a positive effect on the wellbeing of individuals in the community, and that social capital, particularly network and participation rather than trust, plays a moderating role in the relationship between local social enterprise and individual wellbeing. The results help explain how social enterprise improves the wellbeing of community residents as a whole, suggesting practical implications for policymakers and practitioners from governments and social enterprises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social enterprises have come to be regarded as a solution to unstructured crosscutting and complex problems that neither the government nor the market alone can solve (Choi et al., 2019; Weber & Khademian, 2008). Social enterprises pursue not only economic profit but also social value, identifying and addressing long-standing social problems that the government and market have failed to cope with. In addition, social enterprises seek to present innovative and sustainable solutions, such as mechanisms of support and collaboration among diverse actors (Trivedi & Stokols, 2011). In this context, social enterprises have recently been presented as a solution to the various social problems in the society and have been actively introduced and promoted by governments as a policy alternative (Engelke et al., 2015; Kim & Moon, 2017).

Social enterprises differ from businesses or charities, existing “at the crossroads of market, public policies, and civil society” (Defourny & Nyssens, 2007). They are organizations with for-profit activities, that utilize business methods to overcome lack of resources (Dees, 1994; Young, 2001), and are distinct from traditional non-profit organizations that rely on grants and donations. Social enterprises seek to generate revenue from commercial activities (Doherty et al., 2014). Further, they can have additional social, economic, or environmental goals, other than mere profit-making, that are more oriented to the whole community, and place greater emphasis on the general interest (Defourny & Nyssens, 2007). They are considered to create social value by selling or offering social services, programs, and products that fulfill diverse human needs (Mair et al., 2006). Moreover, the long-term goals or values that social enterprises pursue, such as social inclusion and trust, are not strictly tangible―they entail a grand vision of development in which human wellbeing in the general sense is enhanced by particularly fostering those mechanisms that advance it (Scarlato, 2013; Weaver, 2018).

At a policy level, social enterprise is promoted as a cost-effective, flexible, and innovative means of addressing the challenges of providing localized services (Farmer et al., 2012). Especially in the current context of public sector cuts, continued retraction of the state from service delivery, and the subsequent greater involvement of non-state players, social enterprises assume a bigger role in service provision at the community level. At the outset, social enterprises may be initiated by community members to address a community need or want, out of desperation to respond to public service cuts or market failure (Munoz et al., 2014; Steiner et al., 2019). Thus, social enterprises may align themselves to the needs of the local community and act as an effective vehicle for improving the local community’s well-being.

Against this backdrop, a number of studies have suggested a positive association between social enterprises and wellbeing (Elmes Aurora, 2019; Farmer et al., 2020; Mason et al., 2015; Roy et al., 2014). However, most previous research on the impact of social enterprise has taken the form of qualitative studies that used focus groups or interviews with participants or former participants of social enterprise projects to examine their effects on mental and physical health. More empirical research is therefore required to better understand the precise mechanism by which social enterprise influences wellbeing (Macaulay et al., 2017). Moreover, the effect of social enterprise on wellbeing remains controversial, as demonstrated by study findings that certain social enterprises have in fact reduced the wellbeing of their staff by providing them with high-risk and low-quality jobs (Cooney, 2011; Williams & Kadamawe, 2012).

This paper attempts to explore the impact of social enterprise activity by empirically examining the relationship between social enterprise and community wellbeing. Unlike most previous research on the impact of social enterprise, this study empirically investigates the relationship between social enterprise and the experience of wellbeing of individuals in the local community. Two-level multilevel regression models were employed to examine the association between the number of social enterprises in geographical localities and the level of individual life satisfaction as a wellbeing outcome, as such models allow variables from local- and individual-level data to interact under different conditions. In addition, this study examines the potential moderating role of social capital on the relationship between social enterprise and wellbeing in the local community to better understand the mechanism through which social enterprise impacts community wellbeing.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. We first explore the background literature and introduce our analytical framework and hypotheses derived from the previous literature. In the next section, we describe the data collection, measurement, and model specification. We then present the estimation results from two separate analyses, i.e., a multilevel linear regression model and a multilevel ordered logistic regression model. After discussing the significant theoretical and practical issues obtained from the results, we draw a conclusion with policy implications and limitations of this study.

2 Background Literature

2.1 Tackling the “Wicked Problem” of Wellbeing with Social Enterprise in South Korea

The concept of wellbeing offers a useful framework for evaluating public policy, particularly social policy such as the making of public provisions for social security and planning for the fulfillment of basic needs (Hollar, 2003). When we consider the complex characteristics of public policy decisions and their impacts on wellbeing, merely understanding economic conditions is not sufficient. For example, conventional economic measures can be misleading in the identification and evaluation of poverty (Nussbaum & Sen, 1993). We need to know how life is getting better or worse overall. Wellbeing provides a broad, meaningful framework through which to view someone’s situation holistically, and to measure the impact of public policy. Thus, the holistic issue of wellbeing must be considered and utilized in public policy. Moreover, as government activity directly impacts wellbeing, governments should utilize wellbeing as an aim or goal of public policy issues (Coggburn & Schneider, 2003; Gastil, 1970; Glaser et al., 2000).

However, wellbeing is often described as a “wicked problem” that is by nature difficult to define, and for which there is no definitive and objective solution (Bache et al., 2016; Rittel & Webber, 1973). There is no best approach or quick fix to the problems related to wellbeing, as they are interconnected across multiple policy domains, especially in the fields of environment, health, poverty, and unemployment, among others. It might be impossible to resolve all issues related to these problems through government activity alone. Understanding wellbeing as a wicked problem implies that the governments’ role, although necessary, may not alone fix the problem (Bache & Reardon, 2016). To solve it, we should recognize the perspectives and values that shape the definition of the problem itself, and pioneer an entirely new approach from the traditional top-down imposition of technical solutions (Head, 2008). Social enterprises can be construed as a means of providing public services to deal with this complex problem of wellbeing enhancement, as the aim of the social enterprises is to address the wicked problems and achieve social impact using innovative practices (Guo & Bielefeld, 2014; Ranabahu, 2020; Teasdale, 2012). Social enterprises can be utilized as a policy tool with the enactment of institutional support structure, exploring common ground between social- or third-sector organizations and governments about long-term wellbeing goals through collaborative governance and actions.

The South Korean government especially emphasizes the role of social enterprises in enhancing the wellbeing of community residents as a whole. In the Korean context, social enterprises have certain common characteristics. First, the surge of social enterprises came from the need to overcome unemployment triggered by the financial crisis in the late 1990s. In this period, the South Korean government entered into a contract with social enterprises to provide jobs for the unemployed at the local level. As in other countries, their roles have gradually expanded to address broader social problems and create social value, rather than limiting their services to particular groups (Bidet & Eum, 2011; Borzaga & Defourny, 2001; Defourny & Nyssens, 2013; Jung et al., 2016). Second, the rapid growth of social enterprises has mostly been fostered and driven by the governments. The influence of public authorities is rather powerful in South Korea as social enterprises remain dependent on state financial support. Additionally, through their established approval system for social enterprises, the government’s top-down control management is distinct from other countries (Bidet et al., 2018; Defourny et al., 2011; Jung et al., 2016; McCabe & Hahn, 2006).

Specifically, South Korea’s Social Enterprise Promotion Act (SEPA) defines a social enterprise as: an entity that pursues a social objective, aimed at “enhancing the quality of life of community residents” by providing vulnerable social groups with social services or job opportunities, or by contributing to the communities while conducting its business activities, such as the manufacture or sale of goods and services (SEPA, Article 2). Particularly, the Korean government allows only certified social enterprises with a profitable business model and a desirable decision-making process to use the term “social enterprise” based on SEPA. These certified social enterprises can be classified into five types: job creation, social service provision, mixed type, local community development, and miscellaneous. The emergence of diverse types of social enterprises in the country suggests the rise of moral legitimacy of social enterprises that address various social problems (Dart, 2004).

Moreover, the SEPA empowers governments to help social enterprise grow and to use social enterprises as agents to provide government-driven social services. It also stipulates that certified social enterprises can receive public support, such as a time-limited subsidy for additional workers, funding to support the creation of posts for skilled workers, and subsidies for consulting and organizing “Social Enterprise Academies,” which are supported by the Minister of Labor in every province. Subsequently, organizations wishing to be certified and to receive these benefits should provide proof that they are pursuing a social goal aimed at enhancing community wellbeing, including activities that benefit disadvantaged people or related to environmental issues (Bidet & Eum, 2011). The unique nature of the government and social sector partnership can thus be viewed as a form of third-party government (Jung et al., 2016).

2.2 Relationship between Social Enterprise, Wellbeing, and Social Capital

Although wellbeing is a useful umbrella concept for evaluating the overall quality of one’s life, it lacks a coherent conceptual framework. It is highly debatable whether to conceptualize it as an emotional state or use a eudaemonic view. Wellbeing is a complex and multi-faceted construct that requires consideration of diverse dimensions, such as subjective, relational, and material (Brown & Westaway, 2011; Pollard & Lee, 2003; Sumner, 2010; White, 2008). Thus, wellbeing indicates a macro concept concerned with the objective and subjective assessment of how human beings survive, thrive, and function (McNaught, 2011). Additionally, wellbeing and its relationship with other concepts need not be seen as distinct entities, but as parts of a continuum. In fact, wellbeing, subjective wellbeing, satisfaction, utility, and welfare are often used interchangeably (Easterlin, 2001).

There have been numerous studies exploring the relationship between social enterprises and wellbeing (Calò et al., 2018; Farmer et al., 2016, 2020; Roy et al., 2014). First, social enterprises may lead to improved wellbeing of a community through the provision of goods and services meeting important needs of the community residents. Social enterprises fill the gap of unsatisfied social needs resulting from limited government expenditure, specifically by intervening directly through the trading activity and delivery of service in a wide variety of fields, such as personal social services, urban regeneration, and environmental services (Defourny & Nyssens, 2007; Ferri & Urbano, 2011; Hoogendoorn, 2016). Second, social enterprises offer job opportunities to vulnerable or marginalized social groups such as people with diverse disabilities, disadvantaged people, unemployed people, immigrants, women, and those with low qualifications. Those who participated in social enterprises by making products or providing services to their communities have reported enhanced wellbeing (Gordon et al., 2018; Macaulay et al., 2017).

The impact of social enterprise on wellbeing can be further viewed through the existing social capital theories (Calò et al., 2018; Elmes Aurora, 2019; Roy et al., 2014). When it comes to the concept of social capital, there is a long-standing debate on whether it is an individual attribute or a collective property. Yet, recent literature indicates that they are not mutually exclusive (Moore & Kawachi, 2017; Villalonga-Olives & Kawachi, 2015). Cohesion perspectives tend to emphasize one’s trust in others and formal participation in civic associations, while network perspectives emphasize one's informal social ties and the diversity of resources accessible through those ties (Moore & Carpiano, 2019). Another common distinction in social capital is between the cognitive dimension, which reflects subjective attitudes and trust in other people in the neighborhood, and the structural dimension, which includes externally observable aspects of social capital (Grootaert & Van Bastelaer, 2002; Murayama et al., 2012; Uphoff, 2000). Thus, social capital can be categorized into three types: cognitive, network, and structural (Carpiano & Fitterer, 2014; Meng & Chen, 2014; Moore & Carpiano, 2019).

First, social enterprises act as a mechanism for building social capital, by facilitating cooperation and providing an opportunity for people to develop social trust (Roy et al., 2014). Social enterprises may impact the wellbeing of a community through trust as cognitive social capital, which refers to individuals’ perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes toward their social surroundings. For example, people felt that the staff and other participants cared about them (Carpiano & Fitterer, 2014). Social enterprise impacts the wellbeing of a community by generating social enterprise participants, and increasing feelings of inclusiveness, sense of belonging, and trust by giving specific consideration to its core beneficiaries, as part of its social mission (Calò et al., 2018; Farmer et al., 2016).

Second, social enterprises impact the wellbeing of a community through network social capital, i.e., resources that are embedded within an individual’s social networks (Murayama et al., 2012). Extensive literature also exists on the associations between social networks and wellbeing (Awaworyi Churchill & Mishra, 2017; Helliwell & Putnam, 2004; Szreter & Woolcock, 2004). Social enterprise can act as a mechanism for people to strengthen their existing peer support groups and expand their social and supportive networks and cooperate with each other for mutual benefit. Social enterprise supports the building of social capital by connecting individuals through a network of daily interactions within and beyond the social enterprises themselves. So-called “boundary spanners,” or “crossers” have been described to generate network social capital by triggering feelings of connectedness. Boundary spanners are people moving freely between different domains, facilitating relationships with, and between, different community actors (Calò et al., 2018). They are people with connections and roles in community life, who transfer knowledge and learning, create innovation and entrepreneurship, change culture, and help generate social capital (Carpiano & Fitterer, 2014; Farmer et al., 2016).

Third, social enterprise affects wellbeing of a community through structural social capital, which are measures of an individual's civic or social participation. Structural social capital commonly indicates the presence of formal opportunity structures or activities in which individuals build or strengthen their social connections (Moore & Carpiano, 2019; Moore & Kawachi, 2017). Generally, people with higher participation tend to report higher levels of wellbeing (Poortinga, 2006). Social enterprises are reported as providing opportunities for participants to interact, encouraging and supporting them to associate with others. As people value their engagement with others, their involvement in the process of delivering community services through social enterprises increases their wellbeing (Hartley Sandra et al., 2019). Moreover, those people who participate in social enterprises as well as other civic/social organization or activities tend to move through community.

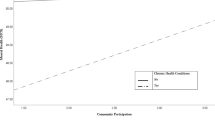

Taken together, to evaluate the overall effect of social enterprise, particularly as a policy alternative to wellbeing enhancement, it is important to establish a relationship between local social enterprise and individual wellbeing that extends beyond the social enterprise and into the whole local community. This study aims to investigate the association of social enterprise and wellbeing with empirical data, focusing on how social enterprises affect wellbeing both within and beyond their own boundaries. We will also examine the moderating role of social capital in the relationship between social enterprise and the individual wellbeing in the local community, which we believe will clarify the wellbeing-enhancing effect of social enterprise. In other words, we argue that as social capital increases, the positive effects of local social enterprises on individual wellbeing will also increase. We will examine the moderating effect of social capital with three measures: first, trust as cognitive and cohesive social capital; second, network connectedness as network social capital; and third, participation as structural social capital (Fig. 1).

Based on this theoretical argument, we established the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Social enterprise has a positive effect on the wellbeing of individuals in the local community.

Hypothesis 2

Social capital has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between social enterprise and the wellbeing of individuals in the local community.

3 Methods

3.1 Data Collection and Measurement

To test the hypotheses, we utilized data from two primary sources. At the individual level, we drew data from the Community Health Survey, which provides the status and level of health conditions at the local level. This survey was conducted through the collaboration of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, universities, and local community health centers. Using stratified sampling, the survey collected comprehensive data about local residents’ demographic information, disease, quality of life, education, and social and physical environments. We utilized 206,888 samples excluding missing values from the survey conducted from the August 16 to October 31 in 2017, covering 17 provinces and 254 cities and equivalent entities across the nation with 228,381 samples. Regarding the cities and equivalent entities, there are three types of administrative entities (City, Gun, and Gu) that are considered equal by South Korea’s Local Autonomy Act. Whereas metro areas include a number of Gun and Gu, non-metro areas consist of City and Gun. Based on the legal provisions, we used cities, local areas, and communities interchangeably in this study. At the local level, we used statistics about social enterprises from the Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency, while statistics about local conditions, such as population density and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, were sourced from Statistics Korea.

In this study, wellbeing outcome, the dependent variable, was drawn from the measure of the life satisfaction question “Taking all things together, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?,” which is rated on a ten-point Likert scale (1 = strongly unsatisfied, 10 = strongly satisfied). Independent variables were collected and measured at the individual and local levels. At the individual level, age was calculated by subtracting each respondent’s year of birth from 2017, the year in which the study was conducted. Age was measured on a six-point scale by decade (1 = 19–29 years old, 6 = 70 years old and above). Gender was measured with a dummy variable (1 = male, 0 = female). Marital status was measured with a dummy variable (1 = living with a spouse, 0 = otherwise). Income was measured with an eight-point Likert scale questionnaire (1 = less than approx. USD 400, 8 = more than approx. USD 5,000 per month). Education was measured by an eight-point Likert scale questionnaire (1 = no education, 8 = graduate school and above).

Three moderating variables were measured: trust of neighborhood as a cognitive social capital, i.e., bonding social capital as particularized trust; network connectedness as network social capital; and participation or engagement as structural social capital. In the original survey question obtained from the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), trust of neighborhood was measured by a dichotomous question, whether a respondent trusts his/her neighborhood (1 = yes, 2 = no). Thus, we applied the variable identical to the survey question but with reverse coding (1 = yes, 0 = no) for easy interpretation. Network was measured with a six-point Likert scale questionnaire (1 = less than once a month, 2 = once a month, 3 = 2 − 3 times a month, 4 = once a week, 5 = 2 − 3 times a week, 6 = more than 4 times a week). To measure participation, the original survey asks a dichotomous question (1 = yes, 0 = no), whether respondents regularly participate at least twice in each religious, fraternal, leisure, charitable activities/organization, the summation of which we used.

At the local level, we employed 254 city-level data as of the year 2017. Social enterprise as a main independent variable was measured by the number of certified social enterprises divided by the number of for-profit firms per 1,000. We utilized certified social enterprises, as this is the only type of enterprise that can receive public support from governments to act as agents to provide social services with the view of accomplishing the socially desired long-term goal of increasing community wellbeing. Population density was measured by population divided by the area of cities, taking natural log. We also incorporated the natural logarithm of GDP per capita, measured by the GDP of cities divided by the population.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, that is, the means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum values of all variables further explored in our modeling.

3.2 Model Specification

As individuals are clustered within local areas, their wellbeing levels may not be independent of one another. With no consideration of the correlation among individuals within the same geographic localities, ordinary least squares regression may overestimate the parameters, causing standard errors of regression coefficients to be underestimated. By allowing error components at a different level of hierarchy, multilevel models were fit to analyze the inherently hierarchical or nested structure of wellbeing data. Some have suggested multilevel analysis as the only valid approach to examining wellbeing outcomes (Ono & Lee, 2016). Multilevel analysis can estimate the magnitude of variances at different levels as well as how these variances relate to explanatory variables. Moreover, the dependent variable is tested to estimate the simultaneous contribution of individual and contextual determinants.

To account for the nested structure of wellbeing outcome within individuals and geographical localities, we used a two-level multilevel model, adjusted for the characteristics that may influence individuals’ wellbeing: age, gender, marital status, income, and education at the individual level, and population density and GDP per capita at the local level. As our dependent variable adopted a Likert table form, our modelling took two forms: multilevel linear models and multilevel logistic models. First, we considered the dependent variable to be continuous, meaning that our model had to be fitted by the normal two-level linear regression model. The function of this model is shown below:

where subscript i refers to an individual case and subscript j refers to the local areas, Yij denotes the life satisfaction score for an individual observation at Level 1. β0j refers to the intercept of the life satisfaction variable in local area j; β1j denotes the slope for the relationship in local area j between the individual predictor and dependent variable; and β2 is the estimate of the slope of the life satisfaction variable in local area j. u0j signifies variation in the intercepts, the deviation of the intercept of a group from the overall intercept; eij represents the random errors of prediction for the Level 1 equation.

Second, we also took the dependent variable as the ordinal variable, since outcome variable is rank ordered on the 10-point scale of life satisfaction, which means that the multilevel mixed-effects ordered logit should be estimated.

Yij shows the probability of the ith respondent of jth local area being each of the life satisfaction scores on the 10-point scale. α0j refers to the intercept of the life satisfaction variable in local area j; α1j is the estimate of a vector of individual and local characteristics of respondent i in local area j; and α2 refers to the estimate of a vector of local characteristics of the level 2 variables that only vary between localities. v0j is an error term on the local level that is assumed to be normally distributed with σv2 variance (vj ~ N (0, σv2)); eij represents the random errors of prediction for the level 1 equation.

4 Results

Collinearity diagnostics were performed before the multi-level analysis as multicollinearity can be a problem for multilevel analysis. Appendix shows the correlations between variables utilized in the following models. No serious risk of multicollinearity was detected. Weak correlations between trust, network, and participation were noticeable, confirming that they are distinct explanatory variables as indicated in previous literature. Even though standard linear OLS regression is discouraged for use as it ignores the nested data structure (Huang, 2018), we conducted it solely to test for collinearity diagnostics, as multicollinearity diagnostics designed for single-level data are also useful for multilevel data (Hox et al., 2017). The OLS regression produced less than 2.5 Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), suggesting no serious problem with multicollinearity. Additionally, some argue that multicollinearity will not pose problems for estimation and inference simply when we have so many cases (Bickel, 2007).

Two approaches were separately constructed to examine the interactions between individual factors and local social enterprise, considering the dependent variable as continuous and then ordinal. The two models, that is, the multilevel linear regression model and multilevel ordered logit regression model, were separately applied to each stage of the models estimating the effects of social enterprise on wellbeing. Hereafter, C denotes the continuous, or linear model, while O denotes the ordinal, or ordered logit model. Starting from the null model with no independent variables, socio-demographic individual characteristics were entered as level 1 variables, and subsequently other contextual level 2 variables as well as the interaction terms between level 1 and level 2 variables were added into the model to analyze the contextual effects.

First, the samples were examined for whether they were fit for multilevel analysis in both models, that is, the multilevel linear regression and multilevel ordered logit model. To verify this, a model with neither level 1 nor level 2 predictors was applied to examine whether the between-groups variance of the dependent variable was significant. As shown in Table 2, the ratio of between-groups to total variance, i.e., ICC (intra-class correlation), was calculated as 1.58 percent for the multilevel linear regression model (Model C1), and 1.71 percent for the multilevel ordered logit model (Model O1), with both of the total variances statistically significant.

Next, level 1 variables were included in Model C2 and Model O2. The results appear to be almost as expected, as outlined in previous literature. Younger females with higher income and education, particularly if married, were found to feel a higher sense of wellbeing. Moreover, people with higher trust as a cognitive social capital, with more networks with neighbors and more participation in various social activities or gatherings have a higher level of wellbeing or greater chances of feeling a higher sense of wellbeing in Model C2 and Model O2.

Model C3 and Model O3 show the two-level random intercept linear regression with individual as well as local variables included. With regard to individual predictors of wellbeing, the results are similar to the previous models, Model C2 and O2. As for the effects of local level explanatory variables, GDP per capita was not associated with wellbeing. However, a negative association was found between population density and wellbeing with statistical significance of 0.1 in Model C3, which was confirmed by Model O3. In particular, a positive relationship emerged in both Model C3 and Model O3 between local social enterprise variable and wellbeing with statistical significance of 0.1. Thus, we can infer a positive association between social enterprise and wellbeing level regardless of the model. Adjusted for other individual and local level variables such as population density and GDP per capita, our results show that an increase in social enterprise raises the level of wellbeing in the local community.

With regard to model fit, the changes in deviance (-log-likelihood ratio) between Model C1 and Model C3 and between Model O1 and Model O3 were statistically significant, confirming the better fit of the more elaborate model from model 1 toward model 3. In addition, level 2 Variance (u0) and ICC constantly decreased from Model C1 to Model C3 and from Model O1 to Model O3, indicating that the models successfully explain the variance between local areas with each progressive step.

Next, we explored whether the local social enterprise variable also interacts with wellbeing at the individual level in relation to social capital. We hypothesized that trust as a cognitive social capital, network social capital, and participation as structural social capital are significantly associated with wellbeing, and that they moderate the association of social enterprises with wellbeing such that a higher level of social capital contributes to a stronger association with wellbeing. In Table 3, Models C4–C6 and O4–O6 examine whether the interactions of local social enterprise with individual wellbeing are associated with individual-level social capital including cognitive trust, network connectedness, and participation or engagement.

Models C4–C6 present a random coefficient linear model with the interaction terms entered separately: social enterprise and trust; social enterprise and network; and social enterprise and participation, respectively. Trust, network social capital, and participation are shown to have a positive moderating role on the relationship between social enterprise at the local level, and wellbeing at the individual level. Higher levels of trust, network, and participation—that is, higher social capital—have a positive effect on this relationship between social enterprise and wellbeing, further enhancing the level of individual wellbeing. When comparing Models C4–C6, the ICC and deviance (-log-likelihood ratio) of Model C5 is the smallest, which indicate that Model C5 (SE and network) is a better fit than Model C4 (SE and trust) or Model C6 (SE and participation).

Model C7, which is better than Models C4–C6 in terms of the model fit criteria of ICC and deviance, shows that trust does not have a moderating effect on the relationship between local social enterprise and individual wellbeing. Thus, it can be said that network social capital and participation as structural social capital have a stronger moderating effect on the relationship between social enterprise and wellbeing than trust as a cognitive social capital. Additionally, the interaction term between SE and network shows more robust correlation with wellbeing with statistical significance of 0.01, compared to that of SE and participation with statistical significance of 0.1.

Models O4–O6 present a random coefficient ordered logit model with interaction terms entered separately: i.e., social enterprise and trust; social enterprise and network; and social enterprise and participation, respectively. Cognitive social capital, network social capital, and structural social capital are shown to have a positive moderating role regarding the relationship between social enterprise at the local level and wellbeing at the individual level. Higher levels of trust, network, and participation have a positive effect on the relationship between social enterprise and wellbeing, further enhancing the level of individual wellbeing. Model O5 (SE and network) is a better fit than Model O4 (SE and trust) or Model O6 (SE and participation) as it shows the smallest ICC and deviance.

In Model O7, the interaction term between SE and trust did not have any statistically significant association with individual wellbeing. Only network social capital and participation have a moderating effect on the relationship between local social enterprise and individual wellbeing. Thus, it is suggested that network social capital and structural social capital have a consistent moderating role than cognitive social capital in the relationship between social enterprise and wellbeing.

Overall, of the hypotheses presented above, Hypothesis 1, that social enterprise will have a positive effect on the wellbeing of individuals in the community, was confirmed with statistical significance of 0.1 both by the multilevel linear model and multilevel ordered logit model. Thus, it can be said that local social enterprise contributes to raising the level of wellbeing of individuals in the local community. Hypothesis 2 is also confirmed with statistical significance of 0.1 in random coefficient linear models (C4–C6), and in random coefficient ordered logit models (O4–O6), with statistical significance of 0.05. Social capital measured as trust, network, and participation moderated the association of SE with wellbeing such that stronger associations between SE and wellbeing were found for a higher level of social capital, regardless of the model.

In addition, the interaction term between SE and trust was not associated with wellbeing with statistical significance both in a multilevel random coefficient linear model (C7) and in a multilevel random coefficient ordered logit model (O7). The results from the two multilevel analyses indicate that network and participation had a moderating role in the relationship between local social enterprise and individual wellbeing regardless of models, but trust did not. Thus, it can be said that network social capital and structural social capital are shown to have consistent and robust moderating roles compared to trust as a cognitively measured social capital.

5 Discussion

Social enterprise has been proposed in various studies as a potential policy intervention as well as a policy alternative to deal with the complex problem of wellbeing enhancement. However, the mechanism between social enterprise and community wellbeing has not been fully expounded, particularly the impact on those outside social enterprises themselves. Previous research mostly lacks empirical data, focusing on qualitative descriptions of wellbeing realized within social enterprises, rather than on how wellbeing enhancement is realized in local communities beyond their boundaries.

We found a positive relationship between social enterprise and the wellbeing of individuals in the local community. We also found that social capital plays a moderating role in the relationship between local social enterprise and individual wellbeing, with the moderating effect of network and participation being stronger than that of trust. The results indicate that social capital and social enterprise interact with each other in their association with individual wellbeing, which may help explain the mechanism by which social enterprise improves individuals’ senses of wellbeing. As individuals’ social capital increases, the positive effects of social enterprise on wellbeing increase further.

This might be because individuals’ social capital, particularly network social capital and participation as structural social capital can facilitate the impact of social enterprise on the wellbeing of people in the local community. While the presence and activities of social enterprise in the local community increase the level of wellbeing in the community as a whole, individuals located in the community can feel a higher level of wellbeing enhancement when they have more network connectedness and participation. This is implied in the previous literature, which argues that wellbeing can be transferred between and beyond social enterprises through networks and participation, or particularly by “boundary spanners,” who can extend the wellbeing-enhancing effect beyond the social enterprise, with connections both in the social enterprise and community life (Ansari et al., 2012; Farmer et al., 2016).

This result also suggests that network social capital and participation as structural social capital are stronger than trust as cognitively measured social capital. Our results demonstrate that social capital measured as trust, network, and participation as a whole moderates the associations of social enterprise in such a way that stronger associations between social enterprise and wellbeing were found for higher levels of social capital. On the other hand, our results indicate that trust as cognitive social capital conceptually distinct from other social capital (Carpiano & Fitterer, 2014), differs from others in its impact on wellbeing through social enterprise. Furthermore, trust is not shown to be robust in its moderating role in the relationship between social enterprise and wellbeing than the others. In other words, our results indicate that social enterprise works mainly as a wellbeing space through network and structural social capital, rather than through trust as cognitive social capital, that is, cohesion or bonding social capital. Similar to our result, loose networks associated with bridging social capital have been found to be critical to economic development, while bonding social capital, such as durable volunteering for an organization, was not found to have any statistical effect on either income or job creation in previous studies (Engbers et al., 2017).

From a public policy perspective, a focus on social capital leads governments to consider the importance of nonmaterial or noneconomic outcomes and assets, through awareness of the social value of maintaining and promoting social capital (Jang et al., 2018; Policy Research Initiative, 2005). Our results also suggest that policymakers and practitioners should consider how to utilize social enterprise and social capital to improve community wellbeing. In general, there are three different tools and strategies for this: using markets and economic resources; using government funding to facilitate infrastructure; and stressing good governance initiatives, which is the most effective (Engbers & Rubin, 2018). Our results suggest that social enterprises as well as governments may enhance wellbeing by fostering the network and structural social capital, coordinating with other partners, and implementing diverse policies and programs through partnership with varied actors. Furthermore, in tackling the wicked problem of wellbeing, social enterprise and governments can act as meta-governors in designing and managing governance frameworks.

Additionally, the impact and concept of social enterprise vary according to historical and social context, including the particular relationships between government, the market, and civil society across regions and countries. For example, social enterprise in the US is primarily conceived of as an innovative business model, while in Europe, it receives direct support as well as a conducive institutional environment from the state. Differences in these regions can be explained by the historical trends formed through the long traditions of market reliance in the United States and state intervention in Europe (Kerlin, 2006). South Korea’s social enterprises are deemed to have a variety of features that distinguish them from similar enterprises in other countries, including a certification system; a high ratio of government subsidy; and specified practices, goals, and values.

6 Conclusions

This study examined the effect of local social enterprises on the wellbeing of people in the local community of South Korea, where the government emphasized the role of social enterprises in enhancing the wellbeing of community residents as a whole, and where SEPA stipulates that social enterprises should pursue the goal of enhancing the wellbeing of community residents.

6.1 Theoretical Implication

This paper provides new evidence in relation to the role and impact of social enterprise in enhancing wellbeing in the local community. First, our study focused on social enterprises as a policy alternative in response to public service cuts or market failure, and attempted to find local-level factors that could contribute to enhancing the wellbeing of individuals in the community. Second, we applied a multilevel framework considering both individual and community level factors, and found a positive correlation between social enterprise and wellbeing in the local community, by corroborating results from two separate analyses, i.e., a multilevel linear regression model and multilevel ordered logistic regression model. Third, we found that social capital moderates the associations of social enterprise in such a way that stronger associations between social enterprise and wellbeing were found for higher levels of social capital, which helps explain the mechanism by which social enterprise contributes to improving individuals’ senses of wellbeing. In addition, our results showed that trust as cognitive social capital differs from network and structural social capital in its impact on wellbeing through social enterprise.

6.2 Practical Implication

The results have important implications for policymakers and practitioners, given that social enterprise has been suggested and conceptualized as a potential policy intervention (Farmer et al., 2016; Macaulay et al., 2017; Munoz et al., 2015). First, it is apparent that social enterprises contribute to enhancing the wellbeing of a community as a whole. For central and local governments alike, providing public service through social enterprises is a better alternative than simply hiring the unemployed or directly subsidizing non-profit organizations. Second, as the effects of social enterprises on wellbeing further increase when individuals have more social capital, especially network connectedness, policymakers and practitioners from governments and social enterprises can contribute to enhancing community wellbeing. They can utilize social enterprise as a more appropriate arena for participation and manage cooperative governance and partnerships with corporate organizations, nongovernmental organizations, neighborhood associations, and religious organizations, as well as informal personal networks.

6.3 Limitations and Future Studies

Our research, based on Korean national statistics and data on certified social enterprises from the Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency, has several limitations. The results cannot be generalized as it is specific to South Korea. Thus, further studies are required to assess the role of social enterprises in enhancing wellbeing in other countries with different contexts, such as varied institutions, government policies and practices, and social cultures. Moreover, this study cannot rule out the possibility that there might be alternate explanations for the effect of social enterprises on wellbeing, as it could not include all the variables presumably associated with the wellbeing of individuals in the local community. Longitudinal information could be incorporated to improve the findings of this study. Additionally, the effect of social capital as a mediator rather than moderator, in the relationship between local social enterprise and individual wellbeing, can be explored in future studies.

References

Ansari, S., Munir, K., & Gregg, T. (2012). Impact at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’: The role of social capital in capability development and community empowerment. Journal of Management Studies, 49(4), 813–842. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01042.x

Awaworyi Churchill, S., & Mishra, V. (2017). Trust, Social Networks and Subjective Wellbeing in China. Social Indicators Research, 132(1).

Bache, I., & Reardon, L. (2016). The politics and policy of wellbeing: Understanding the rise and significance of a new agenda. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bache, I., Reardon, L., & Anand, P. (2016). Wellbeing as a wicked problem: Navigating the arguments for the role of government. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(3), 893–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9623-y

Bickel, R. (2007). Multilevel analysis for applied research: It's just regression!: Guilford Press.

Bidet, E., & Eum, H. S. (2011). Social enterprise in South Korea: History and diversity. Social Enterprise Journal, 7(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508611111130167

Bidet, E., Eum, H., & Ryu, J. (2018). Diversity of social enterprise models in South Korea. VOLUNTAS International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(6), 1261–1273.

Borzaga, C., & Defourny, J. (2001). Conclusions. Social enterprises in Europe: A diversity of initiatives and prospects. In: C. Borzaga, & J. Defourny (Eds.), The emergence of social enterprise (pp. 350–370). New York: Routledge.

Brown, K., & Westaway, E. (2011). Agency, capacity, and resilience to environmental change: Lessons from human development, well-being, and disasters. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 36, 321–342.

Calò, F., Teasdale, S., Donaldson, C., Roy, M. J., & Baglioni, S. (2018). Collaborator or competitor: Assessing the evidence supporting the role of social enterprise in health and social care. Public Management Review, 20(12), 1790–1814.

Carpiano, R. M., & Fitterer, L. M. (2014). Questions of trust in health research on social capital: What aspects of personal network social capital do they measure? Social Science & Medicine, 116, 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.017

Choi, D., Berry, F. S., & Ghadimi, A. (2019). Policy design and achieving social outcomes: a comparative analysis of social enterprise policy. Public Administration Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13111

Coggburn, J. D., & Schneider, S. K. (2003). The relationship between state government performance and state quality of life. International Journal of Public Administration, 26(12), 1337–1354. https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-120024400

Cooney, K. (2011). The business of job creation: an examination of the social enterprise approach to workforce development. Journal of Poverty, 15(1), 88–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2011.539505

Dart, R. (2004). The legitimacy of social enterprise. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14(4), 411–424.

Dees, J. G. (1994). Social enterprise: Private initiatives for the common good: Harvard Business School.

Defourny, J., Kuan, Y. Y., & Kim, S. Y. (2011). Emerging models of social enterprise in Eastern Asia: A cross-country analysis. Social Enterprise Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508611111130176

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2007). Defining social enterprises – at the crossroads of market, public policies and civil society. In M. Nyssens (Ed.), Social enterprise (pp. 19–42): Routledge.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2013). Social innovation, social economy and social enterprise: What can the European debate tell us? In D. M. F. Moulaert, A. Mehmood, & A. Hamdouch (Eds.), The international handbook on social innovation (pp. 40–53). Edward Elgar.

Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 417–436.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal , 111(473), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00646.

Elmes Aurora, I. (2019). Health impacts of a WISE: A longitudinal study. Social Enterprise Journal, 15(4), 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-12-2018-0082

Engbers, T. A., & Rubin, B. M. (2018). Theory to practice: Policy recommendations for fostering economic development through social capital. Public Administration Review, 78(4), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12925

Engbers, T. A., Rubin, B. M., & Aubuchon, C. (2017). The Currency of connections: An analysis of the urban economic impact of social capital. Economic Development Quarterly, 31(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242416666673

Engelke, H., Mauksch, S., Darkow, I.-L., & von der Gracht, H. A. (2015). Opportunities for social enterprise in Germany—Evidence from an expert survey. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 90, 635–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.01.004

Farmer, J., De Cotta, T., McKinnon, K., Barraket, J., Munoz, S.-A., Douglas, H., et al. (2016). Social enterprise and wellbeing in community life. Social Enterprise Journal, 12(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-05-2016-0017

Farmer, J., Hill, C., & Muñoz, S.-A. (2012). Community Co-Production. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Farmer, J., Kamstra, P., Brennan-Horley, C., De Cotta, T., Roy, M., Barraket, J., et al. (2020). Using micro-geography to understand the realisation of wellbeing: A qualitative GIS study of three social enterprises. Health & Place. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102293

Ferri, E., & Urbano, D. (2011). Social entrepreneurship and environmental factors: A cross-country comparison. Research Work International Doctorate in Entrepreneurship and Business Management Department of Business Economics & Administration, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona.

Gastil, R. D. (1970). Social indicators and quality of life. Public Administration Review, 30(6), 596–601. https://doi.org/10.2307/974375

Glaser, M. A., Aristigueta, M. P., & Payton, S. (2000). Harnessing the resources of community: the ultimate performance agenda. Public Productivity & Management Review, 23(4), 428–448. https://doi.org/10.2307/3380562

Gordon, K., Wilson, J., Tonner, A., & Shaw, E. (2018). How can social enterprises impact health and well-being? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(3), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-01-2017-0022

Grootaert, C., & Van Bastelaer, T. (2002). Understanding and measuring social capital: A multidisciplinary tool for practitioners (Vol. 1): World Bank Publications.

Guo, C., & Bielefeld, W. (2014). Social entrepreneurship: An evidence-based approach to creating social value. Wiley.

Hartley Sandra, E., Yeowell, G., & Powell Susan, C. (2019). Promoting the mental and physical wellbeing of people with mental health difficulties through social enterprise. Mental Health Review Journal, 24(4), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-06-2018-0019

Head, B. W. (2008). Wicked problems in public policy. Public Policy, 3(2), 101.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well–being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435–1446.

Hollar, D. (2003). A holistic theoretical model for examining welfare reform: Quality of life. Public Administration Review, 63(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00267

Hoogendoorn, B. (2016). The prevalence and determinants of social entrepreneurship at the macro level. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 278–296.

Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications: Routledge.

Huang, F. L. (2018). Multilevel modeling and ordinary least squares regression: How comparable are they? The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(2), 265–281.

Jang, J., Kim, T.-H., Hong, H., Yoo, C. S., & Park, J. (2018). Statistical estimation of the casual effect of social economy on subjective well-being. VOLUNTAS International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(3), 511–525.

Jung, K., Jang, H. S., & Seo, I. (2016). Government-driven social enterprises in South Korea: Lessons from the social enterprise promotion program in the Seoul Metropolitan Government. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82(3), 598–616.

Kerlin, J. A. (2006). Social enterprise in the united states and europe: understanding and learning from the differences. VOLUNTAS International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-006-9016-2

Kim, T. H., & Moon, M. J. (2017). Using Social Enterprises for social policy in south korea: Do funding and management affect social and economic performance? Public Administration and Development, 37(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1783

Macaulay, B., Roy, M. J., Donaldson, C., Teasdale, S., & Kay, A. (2017). Conceptualizing the health and well-being impacts of social enterprise: A UK-based study. Health Promotion International, 33(5), 748–759. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dax009

Mair, J., Robinson, J., & Hockerts, K. (2006). Social entrepreneurship. Palgrave Macmillan.

Mason, C., Barraket, J., Friel, S., O’Rourke, K., & Stenta, C.-P. (2015). Social innovation for the promotion of health equity. Health Promotion International. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav076

McCabe, A., & Hahn, S. (2006). Promoting social enterprise in Korea and the UK: Community economic development, alternative welfare provision or a means to welfare to work? Social Policy and Society, 5(3), 387.

McNaught, A. (2011). Defining wellbeing. In A. K. A. McNaught (Ed.), Understanding wellbeing: An introduction for students and practitioners of health and social care, (pp. 7–23). Banbury: Lantern

Meng, T., & Chen, H. (2014). A multilevel analysis of social capital and self-rated health: Evidence from China. Health & Place, 27, 38–44.

Moore, S., & Carpiano, R. M. (2019). Measures of personal social capital over time: A path analysis assessing longitudinal associations among cognitive, structural, and network elements of social capital in women and men separately. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.023

Moore, S., & Kawachi, I. (2017). Twenty years of social capital and health research: A glossary. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(5), 513–517.

Munoz, S.-A., Farmer, J., Winterton, R., & Barraket, J. (2015). The social enterprise as a space of well-being: An exploratory case study. Social Enterprise Journal, 11(3), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-11-2014-0041

Munoz, S.-A., Steiner, A., & Farmer, J. (2014). Processes of community-led social enterprise development: Learning from the rural context. Community Development Journal, 50(3), 478–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsu055

Murayama, H., Fujiwara, Y., & Kawachi, I. (2012). Social capital and health: A review of prospective multilevel studies. Journal of Epidemiology, 22(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20110128

Nussbaum, M., & Sen, A. (1993). The Quality of Life: Oxford University Press.

Ono, H., & Lee, K. S. (2016). Redistributing Happiness: How Social Policies Shape Life Satisfaction: How Social Policies Shape Life Satisfaction: ABC-CLIO.

Policy Research Initiative. (2005). Social capital as a public policy tool: Project report. Government of Canada.

Pollard, E. L., & Lee, P. D. (2003). Child well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Social Indicators Research, 61(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021284215801

Poortinga, W. (2006). Social capital: An individual or collective resource for health? Social Science & Medicine, 62(2), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.008

Ranabahu, N. (2020). ‘Wicked’solutions for ‘wicked’problems: Responsible innovations in social enterprises for sustainable development. Journal of Management & Organization, 26(6), 995–1013.

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169.

Roy, M. J., Donaldson, C., Baker, R., & Kerr, S. (2014). The potential of social enterprise to enhance health and well-being: A model and systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 123, 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.031

Scarlato, M. (2013). Social enterprise, capabilities and development paradigms: Lessons from ecuador. The Journal of Development Studies, 49(9), 1270–1283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2013.790962

Steiner, A., Farmer, J., & Bosworth, G. (2019). Rural social enterprise–evidence to date, and a research agenda. Journal of Rural Studies, 70, 139–143.

Sumner, A. (2010). Child poverty, well-being and agency: What does a ‘3-D well-being’approach contribute? Journal of International Development, 22(8), 1064–1075.

Szreter, S., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(4), 650–667.

Teasdale, S. (2012). What’s in a name? making sense of social enterprise discourses. Public Policy and Administration, 27(2), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076711401466

Trivedi, C., & Stokols, D. (2011). Social enterprises and corporate enterprises: Fundamental differences and defining features. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/097135571002000101

Uphoff, N. (2000). Understanding social capital: Learning from the analysis and experience of participation. Social Capital A Multifaceted Perspective, 6(2), 215–249.

Villalonga-Olives, E., & Kawachi, I. (2015). The measurement of social capital. Gaceta Sanitaria, 29, 62–64.

Weaver, R. L. (2018). Re-conceptualizing social value: applying the capability approach in social enterprise research. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 9(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1430607

Weber, E. P., & Khademian, A. M. (2008). Wicked problems, knowledge challenges, and collaborative capacity builders in network settings. Public Administration Review, 68(2), 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00866.x

White, S. C. But what is wellbeing? A framework for analysis in social and development policy and practice. In Conference on regeneration and wellbeing: research into practice, University of Bradford, 2008 (Vol. 2425)

Williams, D. A., & Kadamawe, A. (2012). The dark side of social entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 16, 63–75.

Young, D. (2001). Social enterprise in the United States: Alternate identities and forms. Paper presented at the 1st International EMES Conference: The Social Enterprise: A Comparative Perspective. Trento, Italy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2018S1A3A2075117).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr. Changbin Woo, and Dr. Hyejin Jung commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Woo, C., Jung, H. The Impact of Social Enterprises on Individual Wellbeing in South Korea: The Moderating Roles of Social Capital in Multilevel Analysis. Soc Indic Res 159, 433–454 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02759-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02759-8