Abstract

This article uses random and fixed effects regressions with 743,788 observations from panels of East and West Germany, the UK, Australia, South Korea, Russia, Switzerland and the United States. It shows how the life satisfaction of men and especially fathers in these countries increases steeply with paid working hours. In contrast, the life satisfaction of childless women is less related to long working hours, while the life satisfaction of mothers hardly depends on working hours at all. In addition, women and especially mothers are more satisfied with life when their male partners work longer, while the life satisfaction of men hardly depend on their female partners’ work hours. These differences between men and women are starker where gender attitudes are more traditional. They cannot be explained through differences in income, occupations, partner characteristics, period or cohort effects. These results contradict role expansionist theory, which suggests that men and women profit similarly from moderate work hours; they support role conflict theory, which claims that men are most satisfied with longer and women with shorter work hours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

How many hours of paid work are conducive to human flourishing? Working ever-longer hours eventually leaves people feeling spent; working too few may leave them feeling superfluous. Marx (1966 [1867]: 280) warned of the former, fearing that ever-increasing work hours eventually consume “all time for growth, development and physical health.” Keynes (2010 [1928]: 329) feared the opposite, predicting ever-shorter work hours to lead to “nervous breakdown of the sort which is already common enough in England and the United States amongst the wives of the well-to-do classes, […] who cannot find it sufficiently amusing, when deprived of the spur of economic necessity, to cook and clean and mend.” More than 30 years later, Friedan (1963: 15) diagnosed how, in the stifling gender culture of the 1950s, Keynes’ fear had become reality, diagnosing middle class homemakers to have a widespread “sense of dissatisfaction” from being structurally constrained to stay out of the labor market. However, when women consequently did enter the labor market, average female life satisfaction actually decreased (Stevenson and Wolfers 2009; Treas et al. 2011: 111).

These contradicting observations generated two opposed theories on how working hours influence life satisfaction. Conflict theory argues that an individual’s time and energy are limited. Consequently, individuals feel better when specializing either on employment or homemaking (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985: 77). Expansionist theory argues the opposite, that homemakers profit from taking up paid employment, while full time workers profit from reduced employment to take up a more active role in the household. Consequently, expansionist theory suggests that both men and women profit from moderate work hours (Marks 1977; Barnett and Hyde 2001). By making opposed predictions, these two theories leave unclear how many working hours actually come with the highest life satisfaction for men and women with and without children. The following section illustrates the theories’ different assumptions and derives testable hypotheses from each.

1.1 Conflict Theory

Role conflict theory is based on the premise, that “[t]ime spent on activities within one role generally cannot be devoted to activities within another role” (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985: 77; also cf. Greenhaus and Powell 2006: 64). It therefore assumes that longer workhours not only lead to time pressure outside employment, but also bring conflicting role demands, which lead an individual to have “conflicting views of himself, making impossible a unified self concept” (Goffman 1957: 276). Because role expectations are gendered, “each member of the marriage team plays its special role [and] can sustain the impression that new audiences expect of it” (Goffman 1956: 48; similarly, cf. Dahrendorf 2006 [1959]: 39). Parsons and Bales (1955: 14f) assume that such role expectations are stable, so that women remain “anchored primarily in the internal affairs of the family, as wife, mother and manager of the household, while the role of the adult male is primarily anchored in the occupational world.” More recently, Hakim (2003: 358) argues that while only about 20% of women are career oriented, 20% are home oriented and the rest is in between. Contrary to this, a majority of men have a preference for work. Similarly, others argue that “[f]athers are generally expected to fulfill the role of breadwinner, whereas mothers are expected to be the primary caregiver for children” (Raley et al. 2012: 1424). Deviating from such roles is said to bring “discontent or sanctions from others” (Evertsson and Boye 2018: 473). To avoid this, men and women may “organize their various and manifold activities to reflect or express gender”, whereby “household labor is designated as ‘women’s work’” (West and Zimmerman 1987: 127, 144; also cf. Hook 2010: 1483). While women may therefore see long work hours as an “identity threat”, men may see them as a “masculinity contest” (Williams et al. 2016: 527ff.; also cf. Treas et al. 2011: 113; Greenhaus et al. 2012: 28). Fittingly, empirical studies find that women on average only desire to work 33 h per week across countries, while men desire 38 h (Başlevent and Kirmanoğlu 2014: 38). Women who violate traditional gender norms by out-earning men are less satisfied in their existing marriage, less likely to marry in the first place, more likely to exit the labor market, to divorce and to take on extra housework to restore traditional gender roles (Bertrand et al. 2015: 571). All in all, these approaches suggest that women are more satisfied when spending fewer hours in gainful employment than men.

This should be even more visible for parents, since women tend to shift their identity from worker to caregiver after their first child (Grunow and Evertsson 2016: 271; Evertsson and Boye 2018: 471; Reynolds and Johnson 2012: 133), while men rather associate “the birth of their child with an increased responsibility for them to perform well as an earner” and even to “take on extra work in order to make sure that the family would be well off” (Grunow and Evertsson 2016: 271; also cf. Steiber 2009: 479). Raley et al. (2012: 1425) even suggests that “[b]y supporting a wife’s reduced labor force participation so that she can be more involved in the day-to-day rearing of children, many fathers feel that they provide their children with the best care and nurturance possible—their mother’s care.” Overall, there are thus strong norms for men to increase their labor market participation after having children and for women to reduce theirs. The question is however, if they are indeed more satisfied when they behave in these gender stereotypical ways. If so, then the life satisfaction of fathers should strongly depend on long work hours, the life satisfaction of childless men should depend a bit less on long work hours, that of childless women less yet, while mothers should have the most tenuous link between life satisfaction and long working hours. If this is indeed true over the observation period of the panel studies, then the following hypotheses should be compatible with the data:

Conflict Theory Hypothesis 1

The life satisfaction of childless men increases with working hours and peaks at or even above full time working hours.

Conflict Theory Hypothesis 2

The life satisfaction of fathers increases even more with working hours and peaks at higher working hours than that of childless men.

Conflict Theory Hypothesis 3

The life satisfaction of childless women increases less with working hours and peaks at lower working hours than that of childless men.

Conflict Theory Hypothesis 4

The life satisfaction of mothers increases less with working hours and peaks at lower working hours than that of childless women.

These effects should be more pronounced where gender attitudes prescribe a traditional division of labor (Álvarez and Miles-Touya 2015: 4; van Schoor and Seyda 2011: 35; Grönlund and Öun 2010: 192; Grunow and Evertsson 2016: 285), which leads to the following hypothesis:

Conflict Theory Hypothesis 5

Differences in how working hours influence the life satisfaction of men and women should be more pronounced where traditional gender norms are stronger.

However, while role conflict theory assumes that men and women are most satisfied when adhering to clearly defined gender roles, expansionist theory suggests the opposite.

1.2 Expansionist Theory

Expansionist role theory is based on Sieber’s (1974: 569, 577; also cf. Marks 1977: 926) claim “that role accumulation tends in principle to be more gratifying than stressful.” Expansionist theory therefore claims that “work experiences and family experiences can have additive […] beneficial effects on physical and psychological well-being” (Greenhaus and Powell 2006: 2006). From this perspective, it is wrong to assume that “women and men who engage in ‘unnatural’ roles—for example, the employee role for women and the parental role for men—will experience distress” (Barnett and Hyde 2001: 784; also cf. Gerson 2009: 383; Barnett 2004: 161). Rather, expansionist theory predicts that women experience “frustration and anger […] at home with the children” when this keeps them from paid employment, while fathers who work long hours are unsatisfied due to little contact with their family (Gerson 2017: 26).

Expansionist theory therefore not only argues that “[a]dding the worker role is beneficial to women, and adding or participating in family roles is beneficial for men.” It also suggests that “[t]he benefits of multiple roles depend on the number of roles and the time demands of each. Beyond certain upper limits, overload and distress may occur” (Barnett and Hyde 2001: 784). This suggests that both men and women feel overstrained if they spent either too much time at work or with their family. The theory therefore predicts that men and women are similarly satisfied at moderate working hours that allow to combine work and family (Barnett and Hyde 2001: 786). This leads to the following testable hypothesis.

Expansionist Theory Hypothesis 6

Life satisfaction increases similarly for women and men until moderate work hours are reached, and then declines with increasing work hours.

Role conflict and expansionist theory thus make opposed predictions, both of which come with a normative bias. Role conflict theory can be used to uphold traditional gender norms. Expansionist theory, in turn, “intended to counter the common contention that working mothers hurt children, families, and themselves” (Williams et al. 2016: 520). Who is correct is a matter of heated debate. Gornick and Meyers (2008: 314) promise a “Real Utopia”, if only “men and women engage symmetrically in employment and caregiving.“Hakim (2008: 134) calls this “social engineering to force everyone into the same roles”, while others suggest that couples may “feel more affection and satisfaction within their relationships under traditional gender divisions of labor” (Kornrich et al. 2013: 31f). However, empirical studies could not yet show whether conflict or expansionist theory is more in line with actual data on life satisfaction.

1.3 Empirical Literature and Research Gap

The work-family conflict literature was the first to try to resolve the debate between role conflict and expansionist theory. It showed that men’s longer work hours coincide with a stronger career orientation, while women’s shorter hours coincide with a stronger family orientation (Bielby and Bielby 1989: 785; Greenhaus et al. 2012: 34; Keene and Quadagno 2004: 20). While this suggests that men might be more satisfied at longer workhours than women, this was never tested by the literature, which is seen as an important research gap of this literature (Erdogan et al. 2012: 1058; Grönlund and Öun 2010: 192; Boye 2011: 28; Greenhaus and Powell 2006).

Another literature does measure the impact of working hours on life satisfaction. But it fails to show how the relationship differs between men and women with and without children (Knabe and Rätzel 2010, 78; Rätzel 2012, 1172; Boye 2009, 510f; Pereira and Coelho 2012, 237). Others claim to find differences between men and women, but they do not consider that parenthood may have a gendered effect (Thoits 1986: 270; Treas et al. 2011: 125; Kalmijn and Monden 2012: 369; Angrave and Charlwood 2015: 1507; Dinh et al. 2017: 49). Yet others show conflicting results for the life satisfaction of mothers, but fail to compare this to the effect for fathers (Booth and van Ours 2008, 2009, 2012; Treas et al. 2011; Berger 2013: 38f). While some thus look at the influence of parenthood regardless of gender, others look at the influence of gender regardless of parenthood (Klumb and Lampert 2004: 1016; Schnittker 2007: 229f.). It is therefore still unclear how working hours influence the life satisfaction of mothers, fathers, childless men and childless women differently.

A second problem is that existing studies use dummy variables to measure the influence of non-employment, part and full time employment on life satisfaction (Nordenmark 2004: 117; Cooke and Gash 2010: 1102; Gash et al. 2012: 59). However, this cannot show at which point working hours cease to increase and start to decrease life satisfaction. Reviews of the literature therefore complain that it remains unclear “what the turning point might be” (Dinh et al. 2017: 43), at which working hours cease to increase and start to decrease life satisfaction.

A third problem is that existing studies rely mostly rely on US and UK samples. This leaves unclear which relationships between work hours and life satisfaction are found cross-culturally, and which are culturally specific (Williams et al. 2016: 523; Bielby and Bielby 1989: 786; similarly, cf. Greenhaus and Powell 2006: 88). Using German data, one study shows that indeed, men and especially fathers seem to profit more from working hours than women and especially mothers (Schröder 2018). But this leaves unclear whether similar findings can be observed in other countries. While some cross-country studies suggest that childcare quality, parental leave and tax incentives hardly change how working hours influence the life satisfaction of women (Hamplová 2018: 22; Treas et al. 2011; Steiber 2009: 481; Boye 2011: 27), others suggest that differences in gender attitudes influence the relationship (van Schoor and Seyda 2011: 27; . Schober and Stahl 2016: 603; Schober and Schmitt 2017: 11f.). So far however, no study tested whether the life satisfaction of men and women with and without children is influenced similarly by working hours across countries or whether differences are more pronounced where gender norms are more traditional (Treas et al. 2011: 112; Erdogan et al. 2012: 1062).

Because of these problems, literature reviews complain that “[p]ast research provides contradictory evidence concerning the relationship between work hours and SWB [subjective well-being]” (Pereira and Coelho 2012: 248; also cf. Dinh et al. 2017: 43). The following sections show what data can be used to close this research gap.

2 Data and Methods

2.1 Country- and Survey Selection

I use data from the Cross-National Equivalent File (CNEF), which merges the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (n = 306,678, 1984–2017), the British Household Panel Study and its successor Understanding Society (n = 191,427, 1996–2014), the Australian Panel Study of Household Income and Labour Dynamics (n = 91,896, 2001–2014), the Korea Labor and Income Panel (n = 99,040, 1998–2014), the Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Study (n = 57,195, 1995–2013), the Swiss Household Panel (n = 66,664, 2000–2015) and the United States Panel Study of Income Dynamics (n = 21,598, 2009–2015, cf. all panel studies: Frick et al. 2007).

Since all effects are about working more or less, rather than not working at all, those who are not doing paid work are excluded. The sample is also limited to those 25–64 years old, an age where people typically face a choice between paid work, which I focus on, relative to alternatives such as leisure, household or care work.

The social acceptance of maternal employment in “East Germany shows a closer resemblance to the Scandinavian countries” than to West Germany (Trappe et al. 2015: 234). This should “moderate the relation between full-time employment and wellbeing” (Schober and Schmitt 2017: 9; similarly, cf. Schober and Stahl 2016: 596). I therefore treat East Germany as a separate case from West Germany. This gives eight separate panels to draw inferences from.

While several hundred thousand individual observations exist, panel data exists for only eight countries, which is too little to distinguish why effects systematically differ between countries. Databases such as the World Values Survey contain more countries, but their intra-country samples are neither longitudinal, nor large enough to get reliable results on a per-country basis, which is why the analyses below are only possible with the CNEF. However, because men may be more positively influenced by working hours than women where gender norms are more traditional, I have merged one item from the World Values Survey into each country’s panel study. For each available year and country, this item shows which share of the population agrees with the statement: “When jobs are scarce: Men should have more right to a job than women.” Over the observation period, 12% of US respondents, 18% of Australians, 21% of East Germans, 22% of UK respondents, 24% of West Germans, 29% of Swiss, 46% of Russians and 60% of Koreans agree with this statement (for a graphical presentation, see heading: “Average agreement with traditional gender attitudes from WVS” in the Online Annex). In the following, countries are represented based on how traditional their gender norms are, as measured by this statement. Second, I will pool all countries into one sample, which not only shows an average effect over all countries, but also allows to constrain gender norms to be egalitarian (everyone agrees that women have the same right to jobs as men) and traditional (everyone agrees that men have more right to a job than women). This is used to test whether men profit more from working hours than women where gender norms are more traditional.

2.2 Dependent Variable

Every panel study asked respondents to rate their “satisfaction with life today”, which is the dependent variable of this study. Depending on the country, answers are coded on a 0–10, 1–5 or 1–7 scale. To make answers more comparable, each scale is standardized to have a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 100. Strictly speaking, life satisfaction is measured on an ordinal scale. Under most conditions however, it makes little difference whether it is estimated through an ordered categorical or a linear estimator (Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Ramos 2014, 1018; Bartolini et al. 2013, 173; Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters 2004). I repeated all calculations using categorical models, which did not change the results significantly. Life satisfaction is therefore treated as a linearly scaled variable. Each value on the scale from 0 to 100 can therefore be interpreted as the percentage-share of a country’s maximum attainable life satisfaction.

2.3 Independent Variables

The main independent variable to explain life satisfaction is paid weekly working hours, including overtime, but excluding unpaid household or care work. Some panel studies record last year’s annual work hours, in which case I forwarded values to the next year. For the US Panel Study of Income Dynamics, this was impossible, as it only takes place every two years. The US data therefore shows the influence of last year’s working hours on this year’s life satisfaction. To ensure that this does not influence the results unduly, I have replicated all US effects with the US General Social Survey, yielding substantively similar but more significant results (cf. heading “Comparison results US PSID and GSS” in the Online Annex). However, because the GSS asks about “happiness”, while other panels query life satisfaction and because the GSS is not a panel, I use the PSID in spite of its shortcomings.

Parents are distinguished from non-parents based on the presence of children aged 0–14 in the household (0–18 for Russia due to data limitations). The main calculations were repeated with children aged 0–4, 0–7 and 0–18 with substantially similar results. The chosen age range therefore does not strongly influence the results. As teenagers need less care time than younger children, parents with children above age 14 are coded as childless. However, results are similar when removing them from the calculations altogether.

Sickness may cause both low work hours and low life satisfaction (Klumb and Lampert 2004; Schnittker 2007). I therefore control for subjectively rated health in all regressions. This means that all regressions show how satisfied people are at different working hours while in employment and at constant health. Subjectively rated health was not coded for Korea from 1998 to 2002, where the median health value was therefore assigned. This did not significantly change the results compared to casewise deletion. In all regressions, age is controlled through a linear and non-linear term. Further robustness tests also control for household income, job quality, partner’s life satisfaction, partner’s work hours, intra-household income distribution and period effects. Finally, it is possible that household work hours mediate the relationship between employed work hours and life satisfaction, because, for example, women may be unsatisfied to work longer hours if they also have a lot of hours of work in the household. That the CNEF does not contain household work hours is a weakness. However, for Germany at least, the relationship between hours in employed work and life satisfaction hardly changes when controlling for household work (Schröder 2018: 77). The Online Annex contains descriptive information about all variables and the timeframe of each panel study (see heading “Descriptive data for all relevant variables for each country” in the Online Annex).

3 Method

The first section of the results uses random effects models to regress working hours, working hours squared and working hours cubed on the life satisfaction of each of the four groups (mothers, fathers, childless men and childless women). This tests for a non-linear relationship between working hours and life satisfaction, where working hours may first increase and then decrease life satisfaction. The third degree polynomial allows more complex patterns to emerge if they fit the data better. Since these specifications imply an interaction effect of working hours, working hours squared and working hours cubed with four groups, it is hard to derive effect sizes from regression tables. I therefore show regression tables in the Online Annex only and plot graphs with marginal effects in the results section below.

Random effects regressions show whether those who work longer are also more satisfied. However, they mix a between effect (those who work longer are more satisfied than those who work less) and a within effect (the same person is more satisfied when working longer rather than shorter). While random effects can therefore show whether longer working hours are related to higher life satisfaction in a population, they cannot show causality because those who work longer may be “drawn disproportionately from the ranks of the happy” in the first place (Treas et al. 2011, 114; Pereira and Coelho 2012, 250). The second part of the results section therefore uses fixed effects regressions, which show whether the same person is more satisfied in those years where she works longer. This allows for a more causal inference, as it controls heterogeneity between people. For example, if higher-educated respondents tend to work longer and are more satisfied, then longer work hours would appear to contribute to life satisfaction, even though education explains both work hours and satisfaction. Since fixed effects regressions hold such inter-individual differences constant, they allow to cancel out effects that result from stable differences between individuals, instead showing whether the same person is satisfied when working more or less.

4 Results

4.1 Random Effects: Differences Between Those Who Work Shorter and Longer Hours

The marginal effect plots of Fig. 1 show whether respondents are more satisfied when working more or less, while remaining in employment and at constant health. Each country’s graph has its own y-axis, showing how each group reacts to working hours within each country, rather than showing whether all respondents are more satisfied in one country compared to another. At 20 and 40 h of work per week, vertical dotted lines indicate typical part and full time hours. All regression results behind the plotted effects sizes are in the Online Annex (see the heading “Random Effects regressions results: differences within employment at constant health” in the Online Annex).

Overall, the results are consistent with hypothesis 1 of role conflict theory: The life satisfaction of childless men (green line) increases more steeply with working hours and peaks at higher working hours than the life satisfaction of women (orange and red line), but only marginally so in East Germany.

Hypothesis 2 of role conflict theory is consistent with data from the US, Australia, UK, West Germany, Switzerland and Korea, where fathers (blue line) profit even more from higher working hours than childless men do. In East Germany and Russia, fathers and childless men profit about similarly from high working hours, but each of them profits more from working hours than women and especially mothers. Note however, that differences are not statistically significant where confidence intervals overlap.

Conflict theory hypothesis 3 is consistent with data from every panel, except Eastern German data: childless women profit less from working hours than childless men do. Last, conflict theory hypothesis 4 is confirmed in Australia, East Germany, West Germany and Korea, where the life satisfaction of mothers increases less with working hours than that of childless women does. Indeed, the life satisfaction of mothers only increases significantly with working hours in East Germany, Russia and Korea.

The data is not clear on whether conflict theory hypothesis 5 can be confirmed, since it is not apparent that working hours influence the life satisfaction of men more than of women in countries with more traditional gender norms (Korea, Russia) rather than more egalitarian ones (US, Australia, East Germany).

No country is consistent with hypothesis 6 from expansionist theory however, since no country exists where men and women are most satisfied at similarly moderate working hours. Rather, to sum up the results broadly, it seems that men and especially fathers are more satisfied at longer working hours than women and especially mothers. While the results have so far shown how the life satisfaction of different groups is related to working hours, the following graphs show how the life satisfaction of the same person changes with working hours, allowing a more causal interpretation of the effect of working hours on life satisfaction.

4.2 Fixed Effects: Changes of Working Hours Within the Same Person

The graphs of Fig. 2 show how the life satisfaction of the same person changes when working more or less, while remaining in employment at constant health. As always, age is controlled, and all effects are calculated for those who actually do work, not showing the effect of not working at all, but of working more or less.

This data is again consistent with hypothesis 1 from role conflict theory (for the regression tables behind it, see heading “Fixed Effects regression results: changes of the same person within employment at constant health” in the Online Annex). In every country, a statistically typical childless man is more satisfied during years when he works more. Consistently with Hypothesis 2 of role conflict theory, a typical father in the UK and West Germany experiences an even higher increase of life satisfaction with increasing working hours than a childless man does. Data from all countries except East Germany confirm hypothesis 3 from role conflict theory, that the life satisfaction of a childless woman increases less with working hours than that of a childless man. Last, hypothesis 4 is corroborated with Australian, East German and West German data, where a mother typically profits less from increased working hours than a childless woman does.

Overall, the fixed effects regressions therefore show that in every single country, a statistically typical father gains life satisfaction when increasing his working hours. A typical childless man also does, but often a bit less than a father, while a typical childless woman tends to profit less from longer working hours and a typical mother less yet. Contrary to all other groups, a typical mother is not more satisfied when working longer hours, except possibly in East Germany, Russia and Korea, but the large confidence intervals do not allow any clear inferences.

Hypothesis 6, from role expansion theory, is never correct, as life satisfaction never increases similarly for women and men until moderate work hours are reached, and then declines with increasing work hours. Rather, the overall picture is that the same man and especially father tends to be more satisfied when working longer and less satisfied when working shorter, which is less true for the same woman and especially mother. Since these are within-person results, they control for between-person differences, such as relatively stable gender attitudes or other confounding variables that might bias the results. However, a number of further robustness tests have been conducted to make sure that results are not due to confounding variables.

4.3 Further Robustness Tests

The main results above remain similar when (1) modelling working hours as a categorical variable (0, 20, 40, 60 h), (2) separately calculating effects for households in the lower and upper half of the income distribution, (3) controlling for respondents’ occupation, (4) controlling for partner’s life satisfaction, (4) controlling for partner’s work hours. The results also appear (5) in households where women earn more with each hour of work than men do, which suggests that men profit more from longer work hours, even when it is economically irrational for them to work longer hours than their partners. The results also appear separately (6) in the second and first half of each country’s period and (7) in each country after the year 2008. It therefore does not appear that the results become weaker over time. The life satisfaction of men also (8) does not depend on the working hours of their female partner. Women, in turn, are more satisfied when their male partner works longer hours. This suggests that men’s increase of life satisfaction with working hours does not come at the expense of their partner’s life satisfaction and that women are more satisfied when their male partner is absent for longer. (9) Men may also profit more from working hours due to higher hourly earnings, which yield a higher utility per work hour (cf. Becker 1991 [1981]: 38). I have therefore also controlled for personal income. Whoever has a higher life satisfaction under this condition is more satisfied to work longer, even if this yields no additional income. However, even under this condition, the life satisfaction of men increases more with working hours than that of women, which means that men are more satisfied to work longer than women, even if they do not profit materially from these longer work hours. For all results and a discussion of each, see the heading “Further robustness tests, plotted results and regression tables” in the Online Annex.

4.4 Gender Attitudes

The preceding sections sorted countries based on the prevalence of traditional gender attitudes. However, it was not apparent that differences in how men and women profit from working hours are more pronounced in countries with traditional, rather than egalitarian gender attitudes. Fixed-effects regressions held individual-specific gender attitudes constant. Yet, the result appeared repeatedly that the same man profits more from working longer hours than the same woman does, which makes it unlikely that results are based on individual-level gender attitudes. However, country-level gender attitudes might explain the results, in the sense that if everyone held completely egalitarian gender attitudes, differences in how men and women profit from working hours could be less pronounced.

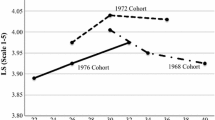

To test this, the following section tests data from all countries in one pooled sample, into which country-level gender attitudes from the World Values Survey have been merged. For this, all life satisfaction values are country-mean centered. The left graph analyzes all countries in one sample, the middle graph shows effects under the “completely egalitarian” condition, where data is constrained so that no one agrees to the statement: “When jobs are scarce: Men should have more right to a job than women.” The right graph shows effects under the “completely traditional” condition, where effects are constrained to show how working hours influence life satisfaction when everyone agrees that men should have preferential access to jobs. The regression table behind these results is found under the heading “Controlling gender attitudes” in the Online Annex.

The left graph of Fig. 3 shows that the characteristic intra-country finding shows up particularly clearly when analyzing all countries together. In the pooled sample, the life satisfaction of childless men clearly increases with working hours; the life satisfaction of fathers increases a bit more with working hours than that of childless men; the life satisfaction of childless women increases less with working hours than the life satisfaction of men does; and finally, mothers who work longer hours are actually less satisfied.

Contrary to this, the effects in the middle graph show that if country-level gender attitudes were completely gender egalitarian, the life satisfaction of everyone except mothers would increase with working hours. But at least under this “completely egalitarian” condition, the life satisfaction of mothers does not decrease with working hours either. The right graph shows that under the contrary condition, where gender attitudes are constrained to be completely traditional, favoring male over female employment, the life satisfaction of women tends to decrease with working hours, while that of men and especially of fathers still increases. This means that if gender attitudes were completely egalitarian (middle graph), mothers and childless women would profit somewhat more from employment than under the currently existing gender attitudes (left graph). If, however, gender attitudes were completely traditional (right graph), then the life satisfaction of women would decrease with working hours, while that of men would increase even more.

This confirms hypothesis number five from role conflict theory, that the stronger increase of life satisfaction with working hours of men and especially fathers relative to women and especially mothers depends partially on country-level gender attitudes. Note however, that even if everyone held entirely egalitarian gender attitudes (middle graph), the life satisfaction of women would still not increase as much with working hours as that of men and especially of fathers does. Thus, while a part of the effect that men profit more from working hours can be explained through country-level gender attitudes, the largest part cannot be explained through the effect of gender attitudes. Note also that the middle graph is completely at odds with what expansionist theory would predict. Based on expansionist theory, men and women would profit similarly from moderate work hours, if gender attitudes were more egalitarian. However, even under this condition, men and especially fathers profit more from working hours than women and especially mothers. In other words, while differences in how much men profit more from working hours than women were smaller in a world with completely gender egalitarian attitudes, such differences would not be eliminated even if everyone held completely egalitarian gender attitudes.

Note also that the life satisfaction values in the middle graph are generally higher than in the right graph, which means that regardless of gender, parental status or working hours, respondents are more satisfied in a country with egalitarian (middle graph) rather than traditional gender attitudes (right graph). To make sure that the results above are not due to specificities of the Cross National Equivalent File data, I have replicated them by using European Social Survey Data, which leads to the same conclusions (see Online Annex heading “Robustness test with European Social survey data”). Thus, two independent data sets confirm that men profit more from working hours than women, partially but not exclusively due to traditional gender attitudes.

5 Discussion

Existing studies show weak and conflicting results about how working hours influence the life satisfaction of women and especially mothers (Booth and van Ours 2008, 2009, 2012; Treas et al. 2011; Berger 2013: 38f; Pereira and Coelho 2012: 248). This paper improved on these conflicting results, by showing how it is unsurprising that existing research found weak results when trying to explain whether women and especially mothers are more satisfied when working longer, because, in fact, they hardly are. This only became apparent by—for the first time—comparing the female effect of working hours on life satisfaction to the effect of men, which showed that men who work shorter hours are significantly less satisfied with life and actually less satisfied than women, while men and especially fathers become more satisfied with life the longer they work, contrary to women and especially mothers. These results can shed light on some hitherto unanswered research questions.

So far, studies are puzzled why women who bear children often prefer relatively few hours in employment and reduce their factual work hours accordingly, while fathers mostly keep on working full time, regardless of their partner’s employment (Greenhaus et al. 2012: 34; Pollmann-Schult and Reynolds 2017: 834; Williams et al. 2016: 517; Raley et al. 2012: 1449; Reynolds and Johnson 2012: 135, 144). The results above indicate that this pattern indeed maximizes life satisfaction. This cannot come about because males who hold traditional gender attitudes work longer and are more satisfied, as fixed effects regressions show that the same man is more satisfied when working longer hours. Contrary to this, the same childless woman experiences less of a life satisfaction increase when working longer hours and a typical mother is not at all more satisfied when working longer rather than shorter hours. These results cannot come about because not working has a different effect on men versus women or parents versus non-parents. It can also not come about because men only reduce their working hours when they are sick, while women have other reasons to reduce their working hours. To the degree that one sees fixed effects regressions as capable of showing causal effects, one can therefore say that long working hours cause a higher life satisfaction in men and especially fathers, relative to women and especially mothers.

Some argue that women reduce their preferred working hours when having children, while men do not, due to specificities of the US labor market (Reynolds and Johnson 2012: 148). However, the results above show that men profit more from longer working hours than women and especially mothers in a variety of countries and irrespective of their type of employment, household income, job quality, partner’s life satisfaction and partner’s work hours. These effects do not seem to become weaker over time and even exist in partnerships where men earn less than women per hour. It is not only striking that men are more satisfied when working longer hours. Interestingly, their female partners are also more satisfied when they work longer hours.

This suggests strongly that role conflict theory is correct across countries for the observed time periods. Role expansion theory, in contrast, is inconsistent with data from every country, as men never feel better when working shorter, moderate working hours, so that men and women are never most satisfied at similarly moderate working hours, contrary to what role expansion theory predicts (Barnett 2004: 161). Apparently, the circumstances which role expansion theory deems necessary for men and women to profit similarly from moderate working hours are not present in any country and not even if everyone held completely egalitarian gender attitudes.

Overall, that the life satisfaction of mother reacts so little to working hours may explain why existing studies could not show “whether employment is beneficial or harmful to mothers” (Hamplová 2018: 3; also cf. the weak conflicting results in Treas et al. 2011: 114; Booth and van Ours 2008, 2009, 2012; Berger 2013: 38f). This gives a new twist to arguments, which claim that it is easier for men to “sustain dual work and family identities” (Bielby and Bielby 1989: 777). This is true in the sense that fathers can be more satisfied than mothers when working very long hours. However, it is wrong, insofar as fathers are much less satisfied at low working hours, so that in this sense they are less capable to “sustain dual work and family identities.” Simply put, while mothers can be satisfied with short or long working hours, fathers only seem satisfied when working long hours. While expansionist theory advocates “policies that make it possible for women to attain equality at work, for men to become equal partners at home” (Gerson 2017: 33), the results indicate that—at least given existing preferences—such policies would actually reduces men’s life satisfaction, while not improving the life satisfaction of women. A good candidate to explain these results is preference theory, which claims that about 20% of women are “home-centered”, 20% are “work-centered”, while 60% are “adaptive”, while a majority of men are work-centered (Hakim 2003: 358f). This would explain why, on average, men tend to profit more from longer working hours, while for women, results seem less clear. However, because preferences were not directly measured in the CNEF, this could not be tested directly and should be a subject for further research.

This is the first study to use longitudinal data to show how working hours influence life satisfaction across countries. However, this data has some limitations. First of all, since only eight panels were used, the number of countries is too small to make general inferences about why differences between men and women, as well as fathers and mothers are sometimes more and sometimes less pronounced.

Also, the data did not allow to control for housework hours. Women may be more stressed to work longer hours, as household work rests predominantly on their shoulders (Boye 2009: 522; Hook 2010). Men and women might therefore be most satisfied at the same level of total work (paid and unpaid). Daycare availability could also mediate the relationship. Mothers may be more satisfied to work longer hours if daycare were better. The results therefore tell little about the world if housework were equally split and daycare availability perfect. While in such a type of world, the predictions of expansionist could be correct, they are not correct in the world that is empirically observable.

References

Álvarez, B., & Miles-Touya, D. (2015). Time allocation and women’s life satisfaction: Evidence from Spain. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1159-3.

Angrave, D., & Charlwood, A. (2015). What is the relationship between long working hours, over-employment, under-employment and the subjective well-being of workers? Longitudinal evidence from the UK. Human Relations, 68(9), 1491–1515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714559752.

Barnett, R. C. (2004). Women and multiple roles: Myths and reality. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12(3), 158–164.

Barnett, R. C., & Hyde, J. S. (2001). Women, men, work, and family. An expansionist theory. American Psychologist, 56(10), 781–796.

Bartolini, S., Bilancini, E., & Sarracino, F. (2013). Predicting the trend of well-being in Germany: How much do comparisons, adaptation and sociability matter? Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0142-5.

Başlevent, C., & Kirmanoğlu, H. (2014). The impact of deviations from desired hours of work on the life satisfaction of employees. Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0421-9.

Becker, G. S. (1991 [1981]). A treatise on the family. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Berger, E. M. (2013). Happy working mothers? Investigating the effect of maternal employment on life satisfaction. Economica, 80(317), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2012.00932.x.

Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., & Pan, J. (2015). Gender identity and relative income within households. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 571–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv001.

Bielby, W. T., & Bielby, D. D. (1989). Family ties: Balancing commitments to work and family in dual earner households. American Sociological Review, 54(5), 776–789. https://doi.org/10.2307/2117753.

Booth, A. L., & van Ours, J. C. (2008). Job satisfaction and family happiness: The part-time work puzzle. The Economic Journal, 118(526), F77–F99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02117.x.

Booth, A. L., & van Ours, J. C. (2009). Hours of work and gender identity: Does part-time work make the family happier? Economica, 76(301), 176–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00670.x.

Booth, A. L., & van Ours, J. C. (2012). Part-time jobs: What women want? Journal of Population Economics, 26(1), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0417-9.

Boye, K. (2009). Relatively different? How do gender differences in well-being depend on paid and unpaid work in Europe? Social Indicators Research, 93(3), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9434-1.

Boye, K. (2011). Work and well-being in a comparative perspective—The role of family policy. European Sociological Review, 27(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp051.

Cooke, L. P., & Gash, V. (2010). Wives’ part-time employment and marital stability in Great Britain, West Germany and the United States. Sociology, 44(6), 1091–1108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510381605.

Dahrendorf, R. (2006 [1959]). Homo sociologicus. Ein Versuch zur Geschichte, Bedeutung und Kritik der Kategorie der sozialen Rolle (16 ed.). Wiesbaden: VS.

Dinh, H., Strazdins, L., & Welsh, J. (2017). Hour-glass ceilings: Work-hour thresholds, gendered health inequities. Social Science and Medicine, 176, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.024.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Truxillo, D. M., & Mansfield, L. R. (2012). Whistle while you work: A review of the life satisfaction literature. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1038–1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311429379.

Evertsson, M., & Boye, K. (2018). The transition to parenthood and the division of parental leave in different-sex and female same-sex couples in Sweden. European Sociological Review, 34(5), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy027.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00235.x.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Ramos, X. (2014). Inequality and happiness. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28(5), 1016–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12049.

Frick, J. R., Jenkings, S. P., Lillard, D. R., Lipps, O., & Wooden, M. (2007). The cross-national equivalent file (CNEF) and its member country household panel studie. Schmollers Jahrbuch: Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften, 127(4), 627–654.

Friedan, B. (1963). The feminine mystique. New York: Norton.

Gash, V., Mertens, A., & Gordo, L. R. (2012). The influence of changing hours of work on women’s life satisfaction. The Manchester School, 80(1), 51–74.

Gerson, K. (2009). Falling back on plan B: The children of the gender revolution face uncharted territory. In B. J. Risman (Ed.), Families as they really are (pp. 378–392). New York: Norton.

Gerson, K. (2017). The logics of work, care and gender change in the new economy: A view from the US. In B. Brandth, S. Halrynjo, & E. Kvande (Eds.), Work-family dynamics. Competing logics of regulation, economy and morals (pp. 19–35). New York: Routledge.

Goffman, E. (1956). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Anchor/Doubleday.

Goffman, I. W. (1957). Status consistency and preference for change in power distribution. American Sociological Review, 22(3), 275–281.

Gornick, J. C., & Meyers, M. K. (2008). Creating gender egalitarian societies: An agenda for reform. Politics & Society, 36(3), 313–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329208320562.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. The Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/258214.

Greenhaus, J. H., Peng, A. C., & Allen, T. D. (2012). Relations of work identity, family identity, situational demands, and sex with employee work hours. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.003.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379625.

Grönlund, A., & Öun, I. (2010). Rethinking work-family conflict: dual-earner policies, role conflict and role expansion in Western Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(3), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928710364431.

Grunow, D., & Evertsson, M. (2016). Narratives on the transition to parenthood in eight European countries: The importance of gender culture and welfare regime. In D. Grunow & M. Evertsson (Eds.), Couples’ transitions to parenthood. Analysing gender and work in Europe (pp. 269–294). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hakim, C. (2003). A new approach to explaining fertility patterns: Preference theory. Population and Development Review, 29(3), 349–374.

Hakim, C. (2008). Is gender equality legislation becoming counter-productive? Public Policy Research, 15(3), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-540X.2008.00528.x.

Hamplová, D. (2018). Does work make mothers happy? Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9958-2.

Hook, Jennifer L. (2010). Gender inequality in the welfare state: Sex segregation in housework, 1965–2003. American Journal of Sociology, 115(5), 1480–1523. https://doi.org/10.1086/651384.

Kalmijn, M., & Monden, C. W. S. (2012). The division of labor and depressive symptoms at the couple level: Effects of equity or specialization? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(3), 358–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407511431182.

Keene, J. R., & Quadagno, J. (2004). Predictors of perceived work-family balance: Gender difference or gender similarity? Sociological Perspectives, 47(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2004.47.1.1.

Keynes, J. M. (2010 [1928]). Economic possibilities for our grandchildren. In J. M. Keynes (Ed.), Essays in persuasion (pp. 321–332). London: Palgrave.

Klumb, P. L., & Lampert, T. (2004). Women, work, and well-being 1950–2000: A review and methodological critique. Social Science and Medicine, 58(6), 1007–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00262-4.

Knabe, A., & Rätzel, S. (2010). Income, happiness, and the disutility of labour. Economics Letters, 107(1), 77–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2009.12.032.

Kornrich, S., Brines, J., & Leupp, K. (2013). Egalitarianism, housework, and sexual frequency in marriage. American Sociological Review, 78(1), 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122412472340.

Marks, S. R. (1977). Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes on human energy. Time and commitment. American Sociological Review, 42(6), 921–936. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094577.

Marx, K. (1966 [1867]). Das Kapital. Band 1, Achtes Kapitel: “Der Arbeitstag”. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

Nordenmark, M. (2004). Multiple social roles and well-being: A longitudinal test of the role stress theory and the role expansion theory. Acta Sociologica, 47(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699304043823.

Parsons, T., & Bales, R. F. (1955). Family, socialization and interaction process. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Pereira, M. C., & Coelho, F. (2012). Work hours and well being: An investigation of moderator effects. Social Indicators Research, 111(1), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0002-3.

Pollmann-Schult, M., & Reynolds, J. (2017). The work and wishes of fathers: Actual and preferred work hours among german fathers. European Sociological Review, 33(6), 823–838. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx079.

Raley, S., Bianchi, S. M., & Wang, W. (2012). When do fathers care? Mothers’ economic contribution and fathers’ involvement in child care. American Journal of Sociology, 117(5), 1422–1459. https://doi.org/10.1086/663354.

Rätzel, S. (2012). Labour supply, life satisfaction, and the (dis)utility of work. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 114(4), 1160–1181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2012.01717.x.

Reynolds, J., & Johnson, D. R. (2012). Don’t blame the babies: Work hour mismatches and the role of children. Social Forces, 91(1), 131–155. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos070.

Schnittker, J. (2007). Working more and feeling better: Women’s health, employment, and family life, 1974–2004. American Sociological Review, 72(2), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240707200205.

Schober, P., & Schmitt, C. (2017). Day-care availability, maternal employment and satisfaction of parents: Evidence from cultural and policy variations in Germany. Journal of European Social Policy, 27(5), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928716688264.

Schober, P. S., & Stahl, J. F. (2016). Expansion of full-day childcare and subjective well-being of mothers: Interdependencies with culture and resources. European Sociological Review, 32(5), 593–606. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw006.

Schröder, M. (2018). How working hours influence the life satisfaction of childless men and women, fathers and mothers in Germany. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 47(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2018-1004.

Sieber, S. D. (1974). Toward a theory of role accumulation. American Sociological Review, 39(4), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094422.

Steiber, N. (2009). Reported levels of time-based and strain-based conflict between work and family roles in Europe: A multilevel approach. Social Indicators Research, 93(3), 469–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9436-z.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2009). The paradox of declining female happiness. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1(2), 190–225. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.1.2.190.

Thoits, P. A. (1986). Multiple identities: Examining gender and marital status differences in distress. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095520.

Trappe, H., Pollmann-Schult, M., & Schmitt, C. (2015). The rise and decline of the male breadwinner model: Institutional underpinnings and future expectations. European Sociological Review, 31(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv015.

Treas, J., van der Lippe, T., & Tai, T.-O. C. (2011). The happy homemaker? Married women’s well-being in cross-national perspective. Social Forces, 90(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/90.1.111.

van Schoor, B., & Seyda, S. (2011). Die individuelle Perspektive: Die Zufriedenheit von Männern und Frauen mit Familie und Beruf. In J. Althammer, M. Böhmer, D. Frey, S. Hradil, U. Nothelle-Wildfeuer, N. Ott, et al. (Eds.), Wie viel Familie verträgt die moderne Gesellschaft? (pp. 23–42). München: Roman Herzog Institut.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender and Society, 1(2), 125–151.

Williams, J. C., Berdahl, J. L., & Vandello, J. A. (2016). Beyond work-life “integration”. Annual Review of Psychology, 67(1), 515–539. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033710.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schröder, M. Men Lose Life Satisfaction with Fewer Hours in Employment: Mothers Do Not Profit from Longer Employment—Evidence from Eight Panels. Soc Indic Res 152, 317–334 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02433-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02433-5