Abstract

This study examines how economic development influences the effects of socio-economic status (SES, measured with education and income) on individuals’ well-being (happiness, self-rated health, and depression) in urban China. Building on Tversky and Griffin’s judgment model of well-being, we propose an endowment and a contrast hypothesis for the variation of SES gradients in well-being across economic contexts. Drawing on six waves of the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2011) and allowing for non-linear development effects, we obtain four main findings: (1) the widely observed SES gradients in physical health are confirmed not only for self-rated health (SRH) but also for happiness and depression among urban residents in China. However, the SES gradients are contingent on economic development in two systematic ways; (2) consistent with both theoretical hypotheses, SES gradients in happiness are positive at lower levels of economic development but become negligible and insignificant at the highest level; (3) consistent with the contrast hypothesis, SES gradients in SRH and depression are substantially smaller at the highest level of economic development. Inconsistent with the endowment hypothesis, these SES gradients are also smaller at the lowest level, suggesting that an impoverished environment can significantly limit the endowment effects of SES; and (4) given the broad support for the contrast hypothesis, we further consider its generating mechanism. A preliminary test does not support the role of relative status, as emphasized by Tversky and Griffin. We therefore discuss two alternative theoretical mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this paper, we use the broader term “well-being” to describe a multi-dimensional concept including both physical health and subjective well-being, as suggested by Diener (2006).

The rationale behind looking at multiple indicators of well-being instead of focusing on one is that the various dimensions of well-being are demonstrated to have different relationships with SES. For example, Kahneman and Deaton (2010) showed that income has a linear positive effect on life satisfaction but that it does not affect emotional well-being when income goes beyond a certain threshold.

For details about the sampling strategy of CGSS, please refer to Bian and Li (2012).

It is worth noting that our data are not panel data at the individual level, so we are unable to control for the individual fixed effects, which would render our estimates of the main effect of SES inaccurate (Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters 2004). We thank one reviewer for pointing out this. However, since our focus is the interaction of SES and regional economic development, the missing individual fixed effects that would induce bias in the estimation of the main effect of SES would not necessarily contaminate the interactions of SES and economic development.

Although our data represent the whole nation, the rural–urban gap is expected to induce complexity when we try to examine the contingency of SES gradients in well-being across levels of economic development; this is because rural areas differ from urban regions not only in economic development but also in other dimensions, such as education (Qian and Smyth 2008) and healthcare (Shi 1993). Unfortunately, we are unable to make these distinctions with the data at hand. We therefore focus on the urban sample only to make the estimations simpler and purer.

“Happiness” has two translations in Chinese; one is more evaluative, xingfu, and the other one is more affective, kuaile. All other waves of CGSS apply the evaluative measure, except for CGSS 2008, which asks about “kuaile”. We test the sensitivity of this measurement inconsistency by replicating the major results with and without CGSS 2008. The qualitative pattern of the results remains the same.

The response categories are different in CGSS 2011: 1 (excellent), 2 (very good), 3 (good), 4 (fair) and 5 (poor). To ensure comparability across waves, we recode the above response to the response category used in CGSS 2008 and 2010. Specifically, “excellent” and “very good” equals to “very healthy”, “good” to “healthy”, “fair” to “average”, and “poor” to “unhealthy”.

0.05 % (N = 144) of the analyzed sample reported zero family income.

Data for China’s annual inflation rate were acquired from the website of “inflation.eu”: http://www.inflation.eu/inflation-rates/china/historic-inflation/cpi-inflation-china.aspx.

Although the standard practice is to use quintiles for the classification of levels of economic development, our exploratory analysis suggests that SES effects on well-being are mostly sensitive at the two extremes of the growth level; we thus create the categories of “≤5 %” and “≥95 %” to capture this pattern.

Similarly, we define five tiers of economic development based on the global distribution for SRH models and, separately, for depression models. For SRH models, the top 5 % tier includes only Beijing and Shanghai and the bottom 5 % tier includes Guizhou, Yunnan, and Gansu. For depression models, the top 5 % tier includes only Shanghai, and the bottom 5 % tier includes Guizhou and Gansu.

To capture the trends of these variables across the observed period, we also present summary statistics by survey year in the online Appendix Table A1. Furthermore, we plot the trend of the three well-being indicators in Appendix Figure A1. In general, our data show quite consistent stagnation for happiness from 2003 to 2011; for health from 2008 to 2011, and depression from 2010 to 2011.

The unusually low proportion for the top 5 % group may be due to the sampling process. In urban areas it is less possible to sample the clustered habitation of most migrants.

Following the suggestion of one reviewer, we have tested the potentially quadratic education effects. All the quadratic terms are statistically insignificant except for depression. Even though, the existing literature does not offer any theory that can interpret this finding. Given the supplementary role of depression in this paper, we decided to leave the systematic examination to future studies.

Whilst the “U-shaped” relationship between age and happiness is widely accepted, not all scholars accept this model. Frijters and Beatton (2012) analyzed three panel datasets and concluded that after controlling for selection effects through fixed effects, the U-shape that bottoms at middle age disappeared.

Our search for developmental contingency is based on a model specification that not only directly corresponds to the notion of interaction but also (1) facilitates the most direct testing of the two hypotheses and (2) avoids the loss of statistical power due to the multicollinearity problem common in the conventional specification of interaction. We have also conducted the traditional tests of interaction effects and the results are shown in the online Appendix Table A2.

The detailed results with different sets of fixed effect controls are available upon request from the authors. As our starting point, models without any fixed effects show positive associations between happiness and per-capita GRP. While this estimation would be biased because the per-capita GRP may be influenced by province-specific characteristics—such as economic policy, natural resources and geographic location—we add dummies for each province to account for this potential problem. As a result, the effects of per-capita GRP have increased in various degrees. Besides the confounding sources from time-invariant factors, the dramatic economic transition during the past several decades is an effect shared by all provinces, so we also add year dummies. The originally significant coefficients for economic development all shrink and become insignificant, suggesting that the majority of observed per-capita GRP effects on happiness can be attributed to economic change during the period under investigation.

Because only two or three waves of data are used, the lack of variability in measures of provincial per-capita GRP renders the estimation particularly susceptible to multicollinearity with province dummies.

This difference may also result from the different samples for happiness models and two other indicators. To check this possibility, we re-ran the happiness Models 1 and 2 of Table 3 using the same three waves of data as the SRH models and the same two waves of data as the depression models. The results are qualitatively the same as those based on all the six waves of data. Thus the sample differences are not the reason.

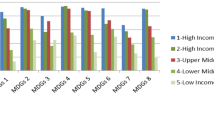

We also present the contextual contingency of the SES gradients across different level of economic development by using 3-D graphs in the online Appendix Figure A2 to A4.

References

Adler, N. E., & Ostrove, J. M. (2006). Socioeconomic status and health: What we know and what we don’t. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896(1), 3–15.

Appleton, S., & Song, L. (2008). Life satisfaction in Urban China: Components and determinants. World Development, 36(11), 2325–2340.

Benzeval, M., & Judge, K. (2001). Income and health: The time dimension. Social Science and Medicine, 52(9), 1371–1390.

Bian, Y., & Li, L. (2012). The Chinese general social survey (2003–8). Chinese Sociological Review, 45(1), 70–97.

Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2001). Making the best of a bad situation: Satisfaction in the Slums of Calcutta. Social Indicators Research, 55(3), 329–352.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7), 1359–1386.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine, 66(8), 1733–1749.

Brockmann, H., Delhey, J., Welzel, C., & Yuan, H. (2009). The China Puzzle: Falling happiness in a rising economy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(4), 387–405.

Caporale, G. M., Georgellis, Y., Tsitsianis, N., & Yin, Y. P. (2009). Income and happiness across Europe: Do reference values matter? Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(1), 42–51.

Case, A., & Paxson, C. (2005). Sex differences in morbidity and mortality. Demography, 42(2), 189–214.

Chen, J., Chen, S., Landry, P. F., & Davis, D. S. (forthcoming). How dynamics of urbanization affect physical and mental health in Urban China. China Quarterly.

Chen, J., & Fleisher, B. M. (1996). Regional income inequality and economic development in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 22(2), 141–164.

Clark, A. E. (2003). Unemployment as a social norm: Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(2), 323–351.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Conti, G., & Heckman, J. J. (2010). Understanding the early origins of the education-health gradient a framework that can also be applied to analyze gene–environment interactions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(5), 585–605.

Crabtree, S., & Wu, T. (2011). China’s puzzling flat line. Gallup Management Journal (August).

Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working paper No. 12352.

Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2010). Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. Journal of Health Economics, 29(1), 1–28.

Deaton, A. (2003). Health, inequality, and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(1), 113–158.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health and wellbeing around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 53–72.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(4), 809–827.

Diener, E. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1(2), 151–157.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 119–169.

Diener, E., Gohm, C. L., Suh, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Similarity of the relations between marital status and subjective well-being across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(4), 419–436.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 94–122.

Dooley, D., Fielding, J., & Levi, L. (1996). Health and unemployment. Annual Review of Public Health, 17(1), 449–465.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic development improve the human lot? In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic development: Essays in Honour of Moses Abramovitz. New York: Academic Press Inc.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27(1), 35–47.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19), 11176–11183.

Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersections of psychology, economics, and demography. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27(4), 463–482.

Easterlin, R. A. (2012). When growth outpaces happiness. The New York Times, published on September 27.

Easterlin, R. A., McVey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness-income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(52), 22463–22468.

Easterlin, R. A., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(25), 9775–9780.

Elo, I. T., & Preston, S. H. (1996). Educational differentials in mortality: United States, 1979–1985. Social Science and Medicine, 42(1), 47–57.

Ettner, S. L. (1996). New evidence on the relationship between income and health. Journal of Health Economics, 15(1), 67–85.

Everson, S. A., Maty, S. C., Lynch, J. W., & Kaplan, G. A. (2002). Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(4), 891–895.

Fahey, T., & Smyth, E. (2004). Do subjective indicators measure welfare? Evidence from 33 European societies. European Societies, 6(1), 5–27.

Fang, P., Dong, S., Xiao, J., Liu, C., Feng, X., & Wang, Y. (2010). Regional inequality in health and its determinants: Evidence from China. Health Policy, 94(1), 14–25.

Feinstein, J. S. (1993). The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: A review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly, 7(2), 279–322.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Frijters, P., & Beatton, T. (2012). The mystery of the U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 82(2), 525–542.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. The American Economic Review, 94(3), 730–740.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2005). The causal effect of income on health: Evidence from German Reunification. Journal of Health Economics, 24(5), 997–1017.

Fujita, F., Diener, E., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Gender differences in negative affect and well-being: The case for emotional intensity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 427.

Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2002). Frustrated achievers: Winners, losers and subjective well-being in new market economies. Journal of Development Studies, 38(4), 100–140.

Gravelle, H. (1998). How much of the relation between population mortality and unequal distribution of income is a statistical artefact? British Medical Journal, 316(31), 382–385.

Hagerty, M. R., & Veenhoven, R. (2003). Wealth and happiness revisited-growing national income does go with greater happiness. Social Indicators Research, 64(1), 1–27.

Helliwell, J. F. (2003). How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well-being. Economic Modelling, 20(2), 331–360.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions - Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435–1446.

Hu, F. (2013). Homeownership and subjective wellbeing in Urban China: Does owning a house make you happier? Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 951–971.

Huisman, M., van Lenthe, F., & Mackenbach, J. (2007). The predictive ability of self-assessed health for mortality in different educational groups. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(6), 1207–1213.

Huppert, F. A., & Whittington, J. E. (2003). Evidence for the independence of positive and negative well-being: Implications for quality of life assessment. British Journal of Health Psychology, 8(1), 107–122.

Idler, E. L., & Angel, R. J. (1990). Self-rated health and mortality in the NHANES-I epidemiologic follow-up study. American Journal of Public Health, 80(4), 446–452.

Jones, A. M., & Wildman, J. (2008). Health, income and relative deprivation: Evidence from the BHPS. Journal of Health Economics, 27(2), 308–324.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2006). Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science, 312(5782), 1908–1910.

Kingdon, G. G., & Knight, J. (2007). Community, comparisons and subjective well-being in a divided society. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 64(1), 69–90.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010). Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural–urban migrants in China. World Development, 38(1), 113–124.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2011). Does economic development raise happiness in China? Oxford Development Studies, 39(1), 1–24.

Krueger, A. B., Kahneman, D., Fischler, C., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2009). Time use and subjective well-being in France and the US. Social Indicators Research, 93(1), 7–18.

Lam, K. C. J., & Liu, P. W. (2013). Socio-economic inequalities in happiness in China and US. Social Indicators Research, 111(3), 1–25.

Lantz, P. M., House, J. S., Lepkowski, J. M., Williams, D. R., Mero, R. P., & Chen, J. (1998). Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality. JAMA, 279(21), 1703–1708.

Layard, R. (2010). Measuring subjective well-being. Science, 327(5965), 534–535.

Li, H., Liu, P. W., Ye, M., & Zhang, J. (2013). Does money buy happiness? Evidence from twins in Urban China. Manuscript, Harvard University.

Li, H., & Zhu, Y. (2006). Income, income inequality, and health: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 34(4), 668–693.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. (1995). Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35(Extra Issue: Forty Years of Medical Sociology: The State of the Art and Directions for the Future), 80–94.

Luttmer, E. F. P. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 963–1002.

Mangyo, E., & Park, A. (2011). Relative deprivation and health which reference groups matter? Journal of Human Resources, 46(3), 459–481.

Marmot, M. G. (2004). Status syndrome: How social standing directly affects your health and life expectancy. London: Bloomsbury.

Marmot, M. G. (2005). Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet, 365(9464), 1099–1104.

Marmot, M. G. (2006). Status syndrome: Achallenge to medicine. JAMA, 295(11), 1304–1307.

Meara, E. R., Richards, S., & Cutler, D. M. (2008). The gap gets bigger: Changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981–2000. Health Affairs, 27(2), 350–360.

Michalos, A. C. (1985). Multiple discrepancies theory (MDT). Social Indicators Research, 16(4), 347–413.

Offer, A. (2006). The challenge of affluence: Self-control and well-being in the United States and Britain Since 1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oswald, A. J., & Wu, S. (2010). Objective confirmation of subjective measures of human well-being: Evidence from the USA. Science, 327(5965), 576–579.

Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., Diez-Roux, A., Kawachi, I., & Levin, B. (2004). “Fundamental Causes” of social inequalities in mortality: A test of the theory. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 45(3), 265–285.

Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., & Tehranifar, P. (2010). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities theory, evidence, and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(suppl.), S28–S40.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 187–224.

Pritchett, L., & Summers, L. H. (1996). Wealthier is healthier. Journal of Human Resources, 31(4), 841–868.

Qi, Y. (2012). The impact of income inequality on self-rated general health: Evidence from a cross-national study. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(4), 451–471.

Qian, X., & Smyth, R. (2008). Measuring regional inequality of education in China: Widening coast–inland gap or widening rural–urban gap? Journal of International Development, 20(2), 132–144.

Senik, C. (2009). Direct evidence on income comparisons and their welfare effects. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 72(1), 408–424.

Shi, L. (1993). Health care in China: A rural–urban comparison after the socioeconomic reforms. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 71(6), 723–736.

Smyth, R., & Qian, X. (2008). Inequality and happiness in urban China. Economics Bulletin, 4(23), 1–10.

Sobal, J., & Stunkard, A. J. (1989). Socioeconomic status and obesity: A review of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 105(2), 260–275.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic development and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox. National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper no. 14282.

Tam, T., & Wu, H. Fei. (2013). Noncognitive traits as fundamental causes of health inequality: Baseline findings from urban China. Chinese Sociological Review, 46(2), 32–62.

Tversky, A., & Griffin, D. (1991). Endowment and contrast in judgments of well-being. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Subjective well-being: An interdisciplinary perspective (Vol. 21, pp. 101–118). New York: Pergamon Press.

Van Praag, B. (2011). Well-being inequality and reference groups: An agenda for new research. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(1), 111–127.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1–34.

Veenhoven, R. (2004). Subjective measures of well-being. World Institute for Development Economics Research, Discussion paper.

Wang, P., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2011). Empirical research on factors related to the subjective well-being of Chinese urban residents. Social Indicators Research, 101(3), 447–459.

Wolbring, T., Keuschnigg, M., & Negele, E. (2011). Needs, comparisons, and adaptation: The importance of relative income for life satisfaction. European Sociological Review, 29(1), 86–104.

Zhang, X., & Kanbur, R. (2005). Spatial inequality in education and health care in China. China Economic Review, 16(2), 189–204.

Zheng, H., & Thomas, P. A. (2013). Marital status, self-rated health, and mortality overestimation of health or diminishing protection of marriage? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(1), 128–143.

Zimmerman, F. J., & Katon, W. (2005). Socioeconomic status, depression disparities, and financial strain: What lies behind the income-depression relationship? Health Economics, 14(12), 1197–1215.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (GRF-446710). We thank Lei Jin for her collaboration in the GRF grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H.F., Tam, T. Economic Development and Socioeconomic Inequality of Well-Being: A Cross-Sectional Time-Series Analysis of Urban China, 2003–2011. Soc Indic Res 124, 401–425 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0803-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0803-7