Abstract

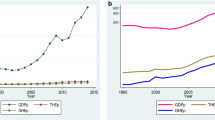

Italian health care expenditure (HCE) has been basically explained with two main groups of theories. (1) Those explaining the peculiarity of the HCE growth as depending on demand and supply factors, such as aging population, number of practising physicians per capita, mix of public and private hospitals, number of hospital beds,… (2) Those explaining the growth of total public expenditure as a common feature among industrialized countries, with a huge empirical literature emphasising the role of GDP and/or other structural/institutional variables as the main determinants of HCE across countries. In order to reassess previous findings, we exploit recent results on panel cointegration analysis and test the regional Italian data on HCE and GDP, also taking into account cross-section correlation. The results show that HCE and GDP are cointegrated. The long- and short-term dynamics of HCE are estimated. Our results, providing an empirical support for the existence of Wagner’s law, have important policy implications in terms of fiscal sustainability: as income rises, people will choose relatively more HCE. Given the level of the public debt in Italy, any further increases would imply that future government spending may be mainly directed toward debt servicing, likely at the expense of public expenditure on basic infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There are, of course, some exceptions. See Di Matteo–Di Matteo (1998) on Canadian Provinces, and Levaggi–Zanola (2003) and Bordignon–Turati (2009) on Italian Regions. In particular, Bordignon–Turati (2009) point out that HCE is generally the result of the behaviour of several layers of government, whose strategic interactions should be considered in the analysis. Their results are specific to the peculiar institutional framework of Italy in the 1990s.

The choice of the base year is a critical decision because of its importance for the considered series. The following aspects have been kept in mind when selecting 2005 as base year: The chosen base year is both a “normal” period and “stable” with respect to the economic activities, i.e., 2005 does not suffer from business cycle fluctuations. It was also felt that it would be desirable to choose a base year like 2005 that is not out of date or out of tune with the universe that it is designed to represent. Finally, 2005 is not distant in the past, this is important because the more recent the base year, the more representative it will be. For a discussion of this issue see, for example, Arulmozhi and Muthulakshmi (2009).

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, in spite of the limited role played by public expenditure in economic activity, Wagner (1883) observed that there exists a relationship between economic growth and public spending, later formulated as ‘Wagner’s Law of Increasing State Activities’.

Franco (1993) gathers the theories interpreting the public expenditure growth into two principal seams. The first includes conflicting-type explanations, according to which the growth of public expenditure depends both on the contrasts among the subjects that make up the society and on the institutions of the country. The second includes those theories of “structural” or “functional” type according to which the expenditure growth is determined by changes in the economic and social structure. In this respect, two relevant paradigms are the already mentioned “Wagner’s law” and the so-called “Tocqueville law”, according to which government expenditure growth with respect to GDP depends on the expansion of the electoral body and on the unequal distribution of income.

They are of two types: one type provides paediatric care to people aged under fourteen, the other type of care is for adults. Their number, role and pay are periodically determined by separate national contracts.

Obviously, individuals are also free to buy private health insurance and to receive treatment at non-contracted private hospitals or consult private outpatient specialists, at their own expense. As in other European countries, with increasing personal income levels, individuals often opt to supplement their public health insurance with the purchase of private insurance and/or private services.

The 1992/1993 reform stated that Regions incurring budget deficits could rely on payroll contributions (previously collected by the central government) earmarked for health care. Regions were also allowed to raise contribution rates. These options, however, were never used. Therefore, the 1990s bail out of the regional health care deficits continued to affect NHS funding.

The 1997 fiscal reform aimed both at eliminating disparities in payroll tax contributions rates and at introducing fiscal decentralisation. Public financing of the NHS partially changed its components as follows: an income-type value added tax on productive activities was introduced with revenues going directly to regions; revenues from user charges and tariffs were paid directly from consumers to local health management units and hospital trusts; regional shares of general taxation collected centrally, and regional surcharges on personal income tax were introduced; an inter-regional equalization fund was created, redistributing extra-revenues from the most affluent to the poorest regions.

Within this context, in 1999, it was decided that, beginning in 2001, health care funding would become a regional responsibility. The definition of essential and uniform assistance levels (LEAs)—the essential benefit package covering all medical care considered necessary, appropriate and cost-effective—was introduced in the system: LEAs were expected to be defined contextually to their financing, namely the capitation rate of public spending granted to each citizen. Responsibilities for ensuring that the general objectives and fundamental principles of the system were maintained at the national level. Regional health authorities were responsible for ensuring the delivery of LEAs through a network of local health management units, including public and accredited private health care providers.

The Financial Law for 2005 first introduced specific forms of support to the Regions by part of Central government. The repayment plans were however introduced with the Financial Law for 2007. The type of support received is related to those activities of planning, management and evaluation of the regional health care in those regions who agreed with the repayment plan inclusive of deficit recovery plan. It involves the activities related both to technical support to the individual region by part of specific central government’s agents (Nuclei) and to monitoring of the (regional and inter-regional) impact of each action implemented by the region subject to the repayment plan.

Over the considered period the regions involved are the following: Abruzzo, Campania, Lazio, Liguria, Molise since 2007, Calabria since 2009 (source: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/temi/p2_4.jsp?area=pianiRientro).

Most residual based cointegration tests require that the long-run parameters for the variables in their levels are equal to the short-run parameters for the variables in their differences. Banerjee et al. (1998) and Kremers et al. (1992) refer to this as a common-factor restriction and show that its failure can cause a significant loss of power for residual-based cointegration tests (Westerlund 2007).

Hansen–King (1996), with a panel of 20 OECD countries over the years 1960–1987, show that the unit root hypothesis for either HCE or GDP can rarely be rejected and their country specific tests rarely reject the hypothesis of no cointegration. Using a panel covering 24 OECD countries between 1960 and 1991, Blomqvist–Carter (1997) conclude that HCE and GDP appear to be nonstationary and cointegrated. Gerdtham–Lothgren (2000), using a panel of 21 OECD countries between 1960 and 1997, and Roberts (2000), with a panel of 10 OECD countries from 1960 to 1993, found evidence suggesting that HCE and GDP are nonstationary variables.

As observed by an anonymous referee, the technical variables used here affect only the hospital beds and general practitioner, whereas no activities (e.g. admissions), needs (e.g. chronic illness), technologies, variables of epidemiological situations and/or policies are considered. The reason is due to unavailability of such variables for all the period of analysis. For example, the variable “admissions” often proxied by the variable “discharges” is contained in the database Istat/Ministero della salute only for the years (1992–2012). The variable “chronic illness” is available, for specific pathologies from 1993 to 2013; moreover ISTAT (Health for all) collects under the chapters related to “disease prevention” and to “chronic disease”, a number of variables, most of which covering only the years 1994, 2000, 2005 and in few cases the period since 1992 on. The variable “technologies” would be proxied by specific instruments such as CAT (computerized axial tomography) or haemodialysis but, in these and other similar cases, data are available from 1997 to 2010. The variables depicting “epidemiological situation” are often proxied by the variables collected by ISTAT (Health for all) under the chapter “Causes of diseases and fatalities” and are available both for the period 1990–2003 and since 2006.

Given this picture, the empirical analysis of long-run relationships among integrated variables with both a cross sectional dimension, N, and a time-series dimension, T, by means of panel cointegration techniques proposed here would be greatly weakened by a reduction of the time dimension of about 8–10 years. Some tests explicitly require T > N, also considering that some periods are lost in the calculation of differenced variables and lags.

As mentioned in previous section, we can distinguish three main periods. 1982–1992: the full financing of HCE by means of the National Health Fund. 1993–1997: a mixed mechanism of financing, with the NHF having a complementary role to the revenues from health care social contributions levying on dependent labour income. 1998–2009: introduction of a regional tax on production activities, a regional surtax on personal income, revenue sharing of the VAT revenue and excise duty on petrol.

The number of lags selected by the Akaike criterion is 2.

The model is fitted allowing panel specific intercepts. The cluster on regions allows for intragroup correlation in the calculation of the standard errors.

The validity of the restrictions shall be tested via Hausman test (Table 5).

Details on the tests are in Pesaran (2007).

Wagner was not explicit in the formulation of his hypothesis. The earliest version of this law was given by Peacock–Wiseman (1961) and then by Pryor (1969) without taking into account the effect of increases in population. In this respect, Gupta (1967) suggested that Wagner’s law may be interpreted as the one wherein growth in real per capita government expenditure depends upon the growth in real GDP per capita. In all these models, Wagner’s law holds true in cases where the elasticity is greater than unity. On the other hand, Timm (1961) concludes that Wagner’s law should be interpreted in a relative sense, as predicting an increasing relative share of public expenditure as per capita real income grows (Henrekson 1993). In this vein, Musgrave (1969) and subsequently Mann (1980) explained the growth in public expenditure in the relative sense, thus supporting the view that Wagner’s law holds true in cases where the value of the elasticity is greater than zero (Henrekson 1993).

K corresponds to 4.957 + 0.183L.log_GDP_PC.

The MG estimator only allows us to impose the restriction in the long-run estimates in order to specify the short-term dynamics.

Wagner gave three main reasons of increasing government expenditure with economic growth. First, with economic growth industrialization and modernization would take place, which will diminish the role of public sector in favour of the private one. This continuous diminishing share of the public sector in economic activity leads to higher government expenditure aimed at regulating the private sector. Second, the rise in real income would lead to more demand for basic infrastructure, such as education and health care, supplied by the government more efficiently than by the private sector. Third, to remove monopolistic tendencies in a country and to enhance economic efficiency in sectors where lumpy investment is required, such as railways, governments should come forward and invest in that particular area, which will again increase government spending (Bird 1971).

Note that two-way causation is frequently the case. Granger causality does not imply that a variable is the effect or the result of the other. Granger causality measures precedence and information content but does not by itself indicate causality in the more common use of the term.

References

Alt, J. (1980). Democracy and public expenditure. St. Louis: Washington University.

Arulmozhi, G., & Muthulakshmi, S. (2009). Statistic for management (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Tata Mc Graw-Hill Education.

Baltagi, B. H., Griffin, J. M., & Xiong, W. (2000). To pool or not to pool: Homogeneous versus heterogeneous estimators applied to cigarette demand. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 82, 117–126.

Banerjee, A., Dolado, J. J., & Mestre, R. (1998). Error-correction mechanism tests for cointegration in a single-equation framework. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 19, 267–283.

Barros, P. P. (1998). The black box of health care expenditure growth determinants. Health Economics, 7, 533–544.

Baum, C. F., Schaffer, M. E., & Stillman, S. (2003). Instrumental variables and GMM: Estimation and testing. Stata Journal, 3, 1–31.

Beraldo, S., Montolio, D., & Turati, G. (2009). Healthy, educated and wealthy: A primer on the impact of public and private welfare expenditures on economic growth. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38, 946–956.

Bethencourt, C., & Galasso, V. (2008). Political complements in the welfare state: Health care and social security. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 609–632.

Bird, R. M. (1971). Wagner’s law of expanding state activity. Public Finance, 26(1), 1–26.

Blomqvist, A. G., & Carter, R. A. L. (1997). Is health care really luxury? Journal of Health Economics, 16, 207–229.

Bohn, H. (1999). Will social security and medicare remain viable as the U.S. population is aging? Carnegie-Rochester Series on Public Policy, 50(1), 1–53.

Bond, S., & Eberhardt, M. (2009). Cross-section dependence in nonstationary panel models: A novel estimator. Paper presented at the Nordic econometrics conference in Lund.

Bordignon, M., & Turati, G. (2009). Bailing out expectations and public health expenditure. Journal of Health Economics, 28, 305–321.

Chari, V. V., & Cole, H. (1995). A contribution to the theory of pork-barrel spending. FRB of Minneapolis discussion paper 156.

Crivelli, L., Filippini, M., & Mosca, I. (2006). Federalism and regional health care: An empirical analysis for the Swiss cantons. Health Economics, 15, 535–541.

Culyer, A. J. (1988). Health care expenditures in Canada: Myth and reality. Canadian tax papers, 82.

Di Matteo, L., & Di Matteo, R. (1998). Evidence on the determinants of Canadian provincial Government health expenditures: 1965–1991. Journal of Health Economics, 17, 211–228.

Eberhardt, M., & Teal, F. (2010). Productivity analysis in global manufacturing production. Economics series working papers 515, University of Oxford, Department of Economics.

Eberhardt, M., & Teal, F. (2011). Econometrics for grumblers: A new look at the literature on cross-country growth empirics. Journal of Economic Surveys, Wiley Blackwell, 25(1), 109–155.

Engle, R., & Granger, C. (1987). Cointegration and error correction: Representation, estimation and testing. Econometrica, 55, 251–276.

Fedeli, S. (2008). La situazione debitoria sanitaria reale delle regioni. La Formazione dei deficit e loro copertura. In Pedone, A. (Ed.), LA SANITA IN ITALIA (pp. 103–138). Milano: Ed. Il sole 24 ORE.

Franco, D. (1993). L’espansione della spesa pubblica in Italia (1960–1990). Bologna: Il Mulino.

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. The Economic Journal, 110, 918–938.

Gerdtham, U.-G., & Jönsson, B. (2000). International comparisons of health expenditure: Theory, data and econometric analysis. In A. J. Culyer & J. P. Newhouse (Eds.), Handbook of health economics (Vol. 1, pp. 11–53). Amsterdam: Noth-Holland.

Gerdtham, U. G., Jönsson, B., MacFarlan, M., & Oxley, H. (1998). The determinants of health expenditure in the OECD countries. In P. Zweifel (Ed.), Health, the medical profession and regulation. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Gerdtham, U. G., & Lothgren, M. (2000). On stationarity and cointegration of international health expenditure and GDP. Journal of Health Economics, 19, 461–475.

Gerdtham, U. G., Sogaard, J., Andersson, F., & Jonsson, B. (1992). An econometric analysis of health care expenditure: A cross-section study of the OECD countries. Journal of Health Economics, 11, 63–84.

Giannoni, M., & Hitiris, T. (2002). The regional impact of health care expenditure: The case of Italy. Applied Economics, 34(14), 1829–1836.

Grilli, V., Masciandaro, D., & Tabellini, G. (1991). Political and monetary institutions and public finance policies in the industrial democracies. Economic Policy, 13, 341–392.

Grofman, B. (2001). Notes and comments. The comparative analysis of coalition formation and duration: Distinguishing between country and within-country effects. British Journal of Political Science, 19, 291–301.

Gupta, S. P. (1967). Public expenditure and economic growth: A time series analysis. Public Finance, 22(4), 423–461.

Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (2004). The value of life and the rise in health spending. NBER working paper, vol. 10737.

Hansen, P., & King, A. (1996). The determinants of health care expenditures: A cointegration approach. Journal of Health Economics, 15, 127–137.

Henrekson, M. (1993). Wagner’s law: A spurious relationship? Public Finance, 48(2), 406–415.

Hitiris, T., & Posnett, J. (1992). The determinants and effects of health expenditure in developed countries. Journal of Health Economics, 11, 173–181.

Im, K. S., Peseran, M., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115, 53–74.

Kremers, J., Ericsson, N., & Dolado, J. (1992). The power of cointegration tests. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 54, 325–348.

Leu, R. E. (1986). The public-private mix and international health care costs. In A. J. Culyer & B. Jonsson (Eds.), Public and private health services. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Levaggi, R., & Zanola, R. (2003). Flypaper effect and sluggishness: Evidence from regional health expenditure in Italy. International Tax and Public Finance, 10, 535–547.

Lijphart, A. (1984). Democracies: Patterns of majoritarian and consensus government in twenty-one countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lijphart, A. (1994). Electoral systems and party systems. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mann, A. J. (1980). Wagner’s law: An econometric test for Mexico, 1925–76. National Tax Journal, 33(2), 189–201.

Milesi-Ferretti, G., Perotti, R., & Rostagno, M. (2002). Electoral systems and public spending. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(2), 609–657.

Moscone, F., & Tosetti, E. (2009). A review and comparison of tests of cross section independence in panels. Journal of Economic Surveys, 27, 528–561.

Musgrave, R. A. (1969). Fiscal systems. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

Newhouse, J. P. (1977). Medical care expenditure: A cross-national survey. Journal of Human Resources, 12, 115–125.

Newhouse, J. P. (1992). Medical care costs: How much welfare loss? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 6(3), 3–21.

Peacock, A., & Scott, A. (2000). The curious attraction of Wagner’s law. Public Choice, 102, 1–17.

Peacock, A. T., & Wiseman, J. (1961). The growth of public expenditure in the United Kingdom. Cambridge: NBER and Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pedroni, P. (1999). Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61, 653–670.

Pedroni, P. (2004). Panel cointegration: Asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Econometric Theory, 3, 579–625.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (1999). The size and scope of government: Comparative politics with rational politicians. European Economic Review, 43, 699–735.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2000). Political economics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2001). Political institutions and policy outcomes: What are the stylized facts? CEPR discussion paper, no. 2872.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2005). The economics effects of constitution. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Persyn, D., & Westerlund, J. (2008). Error-correction-based cointegration tests for panel data. The Stata Journal, 8, 232–241.

Pesaran, H. (2003). A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross section dependence. Cambridge working papers in economics 0346, Faculty of Economics (DAE), University of Cambridge.

Pesaran, M. (2004). General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. Cambridge working papers in economics 435, and CESifo working paper series 1229.

Pesaran, M. (2007). A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22, 265–312.

Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (1997). Estimating long-run relationships in dynamic heterogeneous panels. DAE working papers amalgamated series 9721.

Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y. C., & Smith, R. (1999). Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94, 621–634.

Pesaran, M. H., & Smith, R. (1995). Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 79–113.

Pryor, F. L. (1969). Public expenditure in communist and capitalist nations. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

Roberts, J. (2000). Spurious regression problems in the determinants of health care expenditure: A comment on Hitiris (1997). Applied Economics Letters, 7, 279–283.

Roubini, N., & Sachs, J. (1988). Government spending and budget deficits in the industrial countries. Economic Policy, 8, 100–132.

Roubini, N., & Sachs, J. (1989). Political and economic determination of budget deficits in the industrial democracies. European Economic Review, 33, 903–938.

Rowley, C. K., & Tollison, R. D. (1994). Peacock and Wiseman on the growth of public expenditure. Public Choice, 78, 125–128.

Santagata, W. (1995). Economia, elezioni, interessi. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Smith, J. (1999). Healthy bodies and thick wallets: The dual relation between health and economic status. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(2), 145–166.

Timm, H. (1961). Das Gesetz Des Wachsenden Staatsausgaben. Finanzarchiv, 19, 201–247.

Tornell, A., & Velasco, A. (1992). The tragedy of the commons. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 1208–1231.

Trechsel, A., & Serduult, U. (1999). Kaleidoskop Volksrechte. Die Istitutionen der direkten Demokratie in den schweizerischen Kantonen 1970–1996. Basilea: Helbing and Lichtenhahn.

Vatter, A., & Ruefli, C. (2003). Do political factors matter for health care expenditure? Swiss Cantons. Journal of Public Policy, 23(3), 325–347.

Wagner, A. (1883). Three extracts on public finance. In R. A. Musgrave & A. T. Peacock (Eds.), Classics in the theory of public finance. London: Macmillan.

Weingast, B., Shepsle, K., & Johansen, C. (1981). The political economy of benefits and costs: A neoclassical approach to distributive politics. Journal of Political Economy, 89, 642–664.

Westerlund, J. (2005). New simple tests for panel cointegration. Econometric Reviews, 24, 297–316.

Westerlund, J. (2007). Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69, 709–748.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

1.1 Granger Causality Test on the Considered Variables

The existence of a long run relationship between the government spending for health and GDP advocates that there must be Granger causality in at least one direction. In order, to identify the direction of temporal causality we apply Granger causality tests.

The Granger approach to the question of whether X causes Y is to see how much of the current value of the former can be explained by past values of the latter and then to see whether adding lagged values of X can improve the explanation. Y is said to be Granger-caused by X if X helps in the prediction of Y, or equivalently if the coefficients on the lagged X’s are statistically significant.Footnote 26 Here we report the F-statistics for the test of the null hypothesis that both ln_HCE_PCit does not Granger cause ln_GDP_PCit and ln_GDP_PCit does not Granger cause ln_HCE_PCit, where ln_GDP_PCit and ln_HCE_PCit are taken both in level and in difference.

The results are reported in Table 11, which shows that, for both variables taken both in level and in differences, we can reject the hypothesis that ln_HCE_PCit does not Granger cause ln_GDP_PCit and we do reject the hypothesis that ln_GDP_PCit does not Granger cause ln_HCE_PCit. Therefore, it appears that Granger causality runs two-ways from ln_HCE_PCit to ln_GDP_PCit.

Appendix 2

We test whether ln_GDP_PC and ln_HCE_PC are cointegrated. As already mentioned, we refer to Westerlund (2005, 2007) and Persyn and Westerlund (2008). Their idea is to test the null hypothesis of no cointegration by inferring whether the error-correction term in a conditional panel error-correction model is equal to zero. Recall that the four tests are all normally distributed and are general enough to accommodate unit-specific short-run dynamics, unit-specific trend and slope parameters, and cross-sectional dependence. Two tests are designed to test the alternative hypothesis that the panel is cointegrated as a whole, while the other two test the alternative that at least one unit is cointegrated. The calculated values of the error correction statistics are presented along with asymptotic p values in Table 12. When using the asymptotic p values, for both the cases in which the deterministic chosen is ‘constant and trend’ and ‘constant only’, all four tests clearly lead to accept the null hypothesis of no cointegration, which we take as strong evidence against cointegration between ln_GDP_PC and ln_HCE_PC.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fedeli, S. The Impact of GDP on Health Care Expenditure: The Case of Italy (1982–2009). Soc Indic Res 122, 347–370 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0703-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0703-x