Abstract

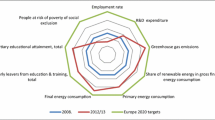

In 2010, EU adopted a new growth strategy which includes three growth priorities and five headline targets to be reached by 2020. The aim of this paper is to investigate the current performance of the EU member and candidate states in achieving these growth priorities and the overall strategy target by allocating the headline targets into the priorities and the priorities into the strategy by the use of a composite indicator methodology. The paper determines how far away each member and candidate state is from the targeted levels of the priorities and the strategy by making a distinction between EU 15 and relatively new member states as well. The developed composite indices enable the observation of the performances of the member and candidate states in a single indicator for the overall strategy and each growth priority. The results of the strategy index and three growth priority indices show that Nordic states possess the highest index scores already having reached many of the targets; many new member states performed as good as EU 15 and some EU 15 states are placed at the bottom of the ranking with quite poor performance in reaching the EU 2020 strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In summarizing these weaknesses, the European Commission (2010) refers to Europe's structurally lower average growth rates and significantly lower employment rates (with fewer average working hours) than its main economic partners, US and Japan; widening productivity gap with the main economic partners, due to lower investment in R&D and innovation; accelerating demographic ageing, strong dependence on fossil fuels such as oil and inefficient use of raw materials in Europe.

The European Commission proposed the strategy package on 3 March 2010 and it was adopted by the European Council in the same month, but the specific target levels were approved in June 2010.

The main head-line targets of the Lisbon are achieving 3% annual GDP growth, 3% share of R&D expenditure in GDP, 70% employment rate (60 and 50% for women and elderly, respectively) and decreasing greenhouse gas emissions by 20% till 2010.

The report by Wim Kok prepared for the Commission to review the midterm performance of the Lisbon Agenda declared that the targets were too ambitious to reach, the political will to satisfy the Lisbon objectives was not sufficient and the slow policy actions did not push economic growth. For these reasons, further growth and job oriented targets were adopted and targets were moderated by the Council (2005).

These objectives were initially defined in the “Energy and Climate Package” which was proposed by European Commission to the Council in January 2008. In December 2008, European Council adopted and EU Parliament endorsed this package and the objectives (European Council 2008).

According to December 2009 European Council conclusions, for the period beyond 2012 till 2020, the EU plans to increase this 20% reduction target to 30%, on condition that other countries commit themselves to satisfying emission reductions (European Commission 2010, p. 9).

Increasing energy efficiency means reducing energy intensity, which is the amount of energy consumed to produce per unit of GDP.

People at risk of poverty are the people having an income level below 60% of the median disposable income (national poverty line) in each member state.

The HDI is a weighted average of three indices; Education index, Life expectancy index and GDP index. Each index measures one or more dimensions. Education index stands for the knowledge level and measures the achievements in a country in the dimensions of adult literacy rate, and combined primary, secondary and tertiary gross enrolment ratios. Life expectancy index shows the value of the dimension of life expectancy at birth and GDP index is the measure of the dimension of decent standard of living. Performance on these dimensions is calculated by using the normalization formula:

$$ {\text{Dimension index}} = \frac{{{\text{Actual value}} - {\text{Minimum value}}}}{{{\text{Maximum value}} - {\text{Minimum value}}}} $$Actual value indicates the score of the country on the dimension in the given year. Minimum value is the lowest value among countries and maximum value is the highest value achieved on that dimension among all the values in the data set. The main reason for using this formula is to acquire index scores between 0 and 1, where the country possessing minimum value gets 0 and the one possessing maximum value gets 1 index score. After calculating each dimension index, the equally-weighted averages of these indices are calculated and the final score is HDI (UNDP 2008, pp. 3–4).

Nordic states are Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.

On average 70 percent of Iceland’s energy consumption was supplied by renewable sources.

Taking the 1990 baseline emission level as 100, in Latvia, the level was around 40 in 2000s. In 10 years, almost 60 percent emission reduction is obtained.

References

Aristovnik, A. & Pungartnik, A. (2009). Analysis of reaching the Lisbon strategy targets at the national level: the EU-27 and Slovenia. Munich Personal Repec Archive Paper, No. 18090, Munich: REPEC.

Barroso, J. M. (2010). Europe: 2020. Presentation to the Informal European Council of 11, February 2010, Brussels.

Böhringer, C., Rutherford, T., & Tol, R. (2009). The EU 20/20/2020 targets: An overview of the EMF22 assessment. Energy Economics, 31(2), 268–273.

Booysen, F. (2002). An overview and evaluation of composite indices of development. Social Indicators Research, 59(2), 115–151.

Codogno, L., Odinet, G., & Padrini, F. (2009). The use of targets in the Lisbon strategy. Economic focus, No. 14. Rome: Ministry of Economy and Finance.

Dijkstra, A. G., & Hanmer, L. C. (2000). Measuring socio-economic gender inequality: Toward an alternative to the UNDP gender-related development index. Feminist Economics, 6(2), 41–75.

Domínguez-Serrano, M., & Blancas, F. J. (2010). A gender wellbeing composite indicator: The best-worst global evaluation approach. Social Indicators Research, 102(3), 477–496.

Erixon, F. (2010). The Europe 2020 strategy: Time for Europe to think again. European View, 9(1), 29–37.

European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Communication from the Commission, COM (2010) 2020, Brussels, 3.3.2010.

European Council. (2000). European council presidency conclusions. 23–24 March 2000, Lisbon. Available at: http://europarl.europa.eu.

European Council. (2005). European council presidency conclusions. 22–23 March 2005, Brussels.

European Council. (2008). European council presidency conclusions. 11–12 December 2008, Brussels.

European Council. (2010). European council presidency conclusions. 17 June 2010, Brussels.

European OECD Joint Commission Research Centre. (2008). Handbook on constructing composite indicators: Methodology and user guide. Paris: OECD.

Eurostat. (2011). Selected statistics: Europe 2020 indicators. Available at: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Accessed March 2010.

Fischer, S., Stefan, G. et al. (2010). Europe 2020: Proposals for the post-Lisbon strategy. International policy analysis. Berlin: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Freudenberg, M. (2003). Composite indicators of country performance: A critical assessment, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No.2003/16, Paris: OECD.

Gelauff, G., & Lejour, A. (2006). Five Lisbon highlights: The economic impact of reaching these targets, Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis Working Paper, No. 104, The Hague: NBEPA.

Hatzigeorgiou, E., Polatidis, H., & Haralambopoulos, D. (2010). Energy CO2 emissions for 1990–2020: A decomposition analysis for EU-25 and Greece. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization and Environmental Effects, 32(20), 1908–1917.

Johansson, B. et al. (2007). The Lisbon agenda from 2000 to 2010. CESIS Electronic Working Paper Series, No. 106, Jönköping: CESIS.

Kok, W. (2004). Facing the challenge: the Lisbon strategy for growth and employment. Report from the high level group, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Lannoo, K. (2010). Europe 2020 and the financial system: Smaller is beautiful. Centre for European Policy Studies Policy Briefs, No. 211. Brussels: CEPS.

Löschel, A., Böhringer, C., Moslener, U., & Rutherford, T. F. (2009). EU climate policy up to 2020: An economic impact assessment. Energy Economics, 31(2), 295–305.

Nardo, M., Saisana, M., Saltelli, A., Tarantola, S., Hoffman, A., & Giovannini, E. (2005). Handbook on constructing composite indicators: Methodology and user guide, OECD Statistics Working Paper, Paris: OECD.

Natali, D. (2010). The Lisbon strategy, Europe 2020 and the crisis in between. European social observatory deliverable. Brussels: OSE.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (2011). The EU 2020 poverty target. UCD Geary institute discussion paper series, Dublin: Geary Institute.

Parker, L. (2010). Climate change and the EU emissions trading scheme (ETS): Looking to 2020. Congressional research service report for congress, 7-5700, 26.01.2010, Washington DC: CRS.

Plantenga, J., Remery, C., Figueiredo, H., & Smith, M. (2009). Towards a European Union gender equality index. Journal of European Social Policy, 19(1), 19–33.

Ruta, M. (2009). Why Lisbon fails? CESifo Economic Studies, 55(1), 145–164.

Tausch, A., & Heshamti, A. (2010). Learning from Latin America’s experience: Europe’s failure in the Lisbon process, Institute for the study of labor discussion paper series, No: 4779, Bonn: IZA.

United Nations Development Programme. (2008). Human development report technical note 1: Calculating the human development indices. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Warleigh-Lack, A. (2011). Greening the European Union for legitimacy? A cautionary reading of Europe 2020. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 23(4), 297–311.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Çolak, M.S., Ege, A. An Assessment of EU 2020 Strategy: Too Far to Reach?. Soc Indic Res 110, 659–680 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9950-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9950-2