Abstract

This paper investigates the role of economic variables in predicting regional disparities in reported life satisfaction of European Union (EU) citizens. European subnational units (regions) are defined according to the first-level EU nomenclature of territorial units. We use multilevel modeling to explicitly account for the hierarchical nature of our data, respondents within regions and countries, and for understanding patterns of variation within and between regions. Main findings are that personal income matters more in poor regions than in rich regions, a pattern that still holds for regions within the same country. Being unemployed is negatively associated with life satisfaction even after controlled for income variation. Living in high unemployment regions does not alleviate the unhappiness of being out of work. After controlling for individual characteristics and modeling interactions, regional differences in life satisfaction still remain, confirming that regional dimension is relevant for life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A notable exception is the recent analysis of regional well-being in Europe by using European Social Survey data of Aslam and Corrado (2007).

Because of data deficiencies, Sweden and Finland are considered as whole countries and the French Départements D’Outre-Mer are excluded.

These findings are in accordance to the ones obtained by Scoppa and Ponzo (2008) who used data on Italians subjective well-being from the Bank of Italy Survey of Household Income and Wealth.

Estimates of the models are obtained by the lmer function in R (R Development Core Team 2006) and are based on the restricted maximum likelihood procedure (REML). The REML procedure corrects the downwards bias of the maximum likelihood estimator of variance components related to the lost of degrees of freedom in estimating the fixed effects. The name lmer stands for linear mixed effects in R but the function works also for generalized linear models. However some technical challenges exist in fitting multinomial models in a multilevel framework. Therefore, for the ordered logit model we use the classical no-pooling regression. The term “mixed effects” refers to random effects (coefficients that vary by group) and fixed effects (coefficient that do not vary) (Gelman and Hill 2007).

As pointed out by, e.g., Di Tella et al. (2003) and Frey and Stutzer (2006), estimated effects should be treated with caution since some personal characteristics can be considered endogenous. Moreover if unobserved personal traits influence reported life satisfaction, results suffer from potential bias.

Due to data availability in the European regional data set we use in models with more complex multilevel structure, we report for coherence the results of the fitting for the period 1997–2002. However, we did not find any significant difference when we use the Eurobarometer data expanding the period backward to 1992. Detailed results of the fitted models are available upon request from the authors.

Income is treated as a continuous variable and centered to reduce the correlation between group-level intercepts and slopes. We allow the coefficients of each employment category to vary. In line with our goal, results are focused only on the unemployment status.

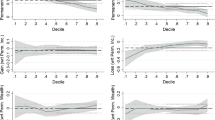

We implemented the weighted local polynomial regression (LOWESS, LOcally WEighted Scatterplot Smoother), as proposed by Cleveland (1979). As Cleveland discusses, rather than calculating one regression line for an entire dataset, one calculates regression estimates for overlapping sets of x values. To find smoothed values, the procedure fits n polynomial regressions to the data, one for each observation j, including the points with x-values that are near x j . We implemented this model in R by choosing an appropriate smoothing span that gives the proportion of points in the plot which influence the amount of smoothing at each value. The choice of the LOWESS procedure among other possible approaches of “smoothing” relies on its robustness to the presence of outliers.

Adding per capita GDP in the model for the whole period (1997–2002) is problematic as a potentially non stationary predictor (the GDP) is introduced to explain an outcome that is naturally stationary (the life satisfaction rated on a four-point scale). Therefore, the estimated coefficients may be “unpersuasive” due to the inapplicability of conventional statistical procedures (Di Tella et al. 2003). The (stochastic) trend of the non stationary variable will in fact dominate all other variations. To overcome this problem we prefer to model the time-series structure of our dataset repeating the model year-by-year. The method of repeated modeling, followed by time-series plots of estimates is rarely used as a data analytic tool but it can be very informative and easy to understand.

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Aslam, A., & Corrado, L. (2007). No man is an island: The inter-personal determinants of regional well-being and life satisfaction in Europe. Cambridge Working Paper in Economics, CWPE 0717.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2001). Do people mean what they say? Implications for subjective survey data. American Economic Review, 91, 67–72.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Clark, A. (2003). Unemployment as a social norm: Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Labor Economic, 21(2), 323–351.

Clark, A., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. Economic Journal, 104, 648–659.

Cleveland, W. S. (1979). Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatter plots. Journal of American Statistical Association, 74, 829–836.

Diener, E. Sandvik, E., Seidlitz, L., & Diener, M. (1993). The relationship between income and subjective well-being: Relative or absolute? Social Indicators Research, 28, 195– 223.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R., & Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from happiness surveys. American Economic Review, 91(1), 335–42.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 809–827.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. David & M. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth. New York: Academic Press.

European Commission. (2008). A new partnership for cohesion convergence competitiveness cooperation. Third report on economic and social cohesion.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. Economic Journal, 110, 918–938.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics: How the economy and institutions affect human well-being. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2006). Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married. Journal of Socio-Economics, 35(2), 326–347.

Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gelman, A., Park, D. K., Shor, B., Bafumi J., & Cortina G. (2008b). Red state, blue state, rich state, poor state: Why Americans vote the way they do. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gelman, A., Shor, B., Bafumi, J., & Park, D. (2008a). Rich state, poor state, red state, blue state: What’s the matter with Connecticut? Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 2, 345–367.

Graham, C., & Felton, A. (2006). Inequality and happiness: Insights from Latin America. Journal of Economic Inequality, 4(1), 1569–1721.

Inglehart, R. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 3–24.

Krueger, A. B., & Schkade, D. A. (2007). The reliability of subjective well-being measures. NBER Workin Paper No. 13027.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. New York: Penguin Press.

Longford, N. T. (2007). Missing data and small-area estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Oswald, A. J.(1997). Happiness and economic performance. Economic Journal, 107, 1815– 1831.

Pittau, M. G., & Zelli, R. (2006). Empirical evidence of income dynamics across EU regions. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 21, 605–628.

R Development Core Team. (2006). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Schmitt, H., & Scholz, E. (2005). The Mannheim Eurobarometer Trend File, 1970–2002 [Computer file]. Prepared by Zentralarchiv fur Empirische Sozialforschung. ICPSR04357-v1. Mannheim, Germany: Mannheimer Zentrum fur Europaische Sozialforschung and Zentrum fur Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen [producers]. Cologne, Germany: Zentralarchiv fur Empirische Sozialforschung/Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributors].

Scoppa, V., & Ponzo, M. (2008). An empirical study of happiness in Italy. B. E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 8(1) (Contributions), article 15.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis. London: Sage.

Tanzi, V., & Davoodi, H. R. (2000). Corruption, growth and public finances. IMF Working Paper No. 182.

Veenhoven, R. (2007). World database of happiness, distributional findings in nations. Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

Warr, P. B., & Jackson, P. (1987). Adopting to the unemployed role; a longitudal investigation. Social Science Medicine, 25, 1219–1224.

Wilkinson, W. (2007). In pursuit of happiness research. Is it reliable? What does it imply for policy? Policy Analysis, 590, 1–41.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Economica, 65(257), 1–15.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Columbia University, Applied Statistics Center, and the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health for financial support. They also acknowledge Sapienza, University of Rome, for financial assistance under grant number C26F07R754. They would like to thank an anonymous reviewer and participants of the XXX IARIW conference, Portoroz, Slovenia, August 2008, for their precious comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pittau, M.G., Zelli, R. & Gelman, A. Economic Disparities and Life Satisfaction in European Regions. Soc Indic Res 96, 339–361 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9481-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9481-2