Abstract

The Mohorovičić discontinuity is the boundary between the Earth’s crust and mantle. Several isostatic hypotheses exist for estimating the crustal thickness and density variation of the Earth’s crust from gravity anomalies.

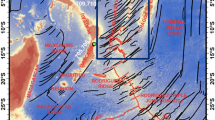

The goal of this article is to compare the Airy-Heiskanen and Vening Meinesz-Moritz (VMM) gravimetric models for determining Moho depth, with the seismic Moho (CRUST2.0 or SM) model. Numerical comparisons are performed globally as well as for some geophysically interesting areas, such as Fennoscandia, Persia, Tibet, Canada and Chile. These areas are most complicated areas in view of rough topography (Tibet, Persia and Peru and Chile), post-glacial rebound (Fennoscandia and Canada) and tectonic activities (Persia).

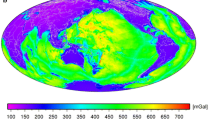

The mean Moho depth provided by CRUST2.0 is 22.9 ± 0.1 km. Using a constant Moho density contrast of 0.6 g/cm3, the corresponding mean values for Airy-Heiskanen and VVM isostatic models become 25.0 ± 0.04 km and 21.6 ± 0.08 km, respectively. By assuming density contrasts of 0.5 g/cm2 and 0.35 g/cm3 for continental and oceanic regions, respectively, the VMM model yields the mean Moho depth 22.6 ± 0.1 km. For this model the global rms difference to CRUST2.0 is 7.2 km, while the corresponding difference between Airy-Heiskanen model and CRUST2.0 is 11 km. Also for regional studies, Moho depths were estimated by selecting different density contrasts. Therefore, one conclusion from the study is that the global compensation by the VMM method significantly improves the agreement with the CRUST2.0 vs. the local compensation model of Airy-Heiskanen. Also, the last model cannot be correct in regions with ocean depth larger than 9 km (e.g., outside Chile), as it may yield negative Moho depths. This problem does not occur with the VMM model. A second conclusion is that a realistic variation of density contrast between continental and oceanic areas yields a better fit of the VMM model to CRUST2.0. The study suggests that the VMM model can primarily be used to densify the CRUST2.0 Moho model in many regions based on separate data by taking advantage of dense gravity data.

Finally we have found also that the gravimetric terrain correction affects the determination of the Moho depth by less than 2 km in mean values for test regions, approximately. Hence, for most practical applications of the VMM model the simple Bouguer gravity anomaly is sufficient.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Airy G.B., 1855. On the computations of the effect of the attraction of the mountain masses as disturbing the apparent astronomical latitude of stations in geodetic surveys. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London B, 145, 101–104.

Albertella A., Migliaccio F. and Sansò F., 2002. GOCE: The Earth field by space gradiometry. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 83, 1–15.

Balmino G., Perosanz F., Rummel R., Sneeuw N., Sünkel H. and Woodworth P., 1998. European Views on Dedicated Gravity Field Missions: GRACE and GOCE. Earth Sciences Division Consultation Document, ESA, ESD-MAG-REP-CON-001.

Bassin C., Laske G. and Masters T.G., 2000. The current limits of resolution for surface wave tomography in North America. EOS Trans. AGU, 81, F897.

Bowie W., 1927. Isostasy. E.P. Dutton & Company, New York.

Braitenberg C., Zadro M., Fang J., Wang Y. and Hsu H.T., 2000. The gravity and isostatic Moho undulations in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Geodyn., 30, 489–505.

Cordell L. and Henderson R.G., 1968. Iterative three-dimensional solution of gravity anomaly data using a digital computer. Geophysics, 38, 596–601.

Čadek O. and Martinec Z., 1991. Spherical hermonic expansion of the earth’s crustal thickness up to degree and order 30. Stud. Geophys. Geod., 35, 151–165.

Dyrelius D. and Vogel A., 1972. Improvement of covergency in iterative gravity interpretation. Geophys. J. R. Astron. Soc., 27, 195–205.

ESA, 1999. Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Mission. ESA SP-1233(1), ESA Publications Division, pp. 217.

Fowler C.M.R., 2001. The Solid Earth: an Introduction to Global Geophysics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

Laske G., Masters G. and Reif C., 2000. A New Global Crustal Model at 2×2 Degrees (CRUST2.0). http://igppweb.ucsd.edu/~gabi/rem.dir/crust/crust2.html.

Geiss E., 1987. A new compilation of crustal thickness data for the Mediterranean area. Ann. Geophys., 5B, 623–630.

Gómez Oritz D. and Agarwal B.N.P., 2005. 3DINVER.M: a MATLAB program to invert the gravity anomaly over a 3D horizontal density interface by Parker-Oldenburg’s algorithm. Comput. Geosci., 31, 513–520, DOI: 10.1016/j.candgeo.2004.11.004.

Haines S.S., Klemperer S.L., Brown L., Jingru G., Mechie J., Meissner R., Ross A. and Wenjin Z., 2003. INDEPTH III seismic data: From surface observations to deep crustal processes in Tibet. Tectonics, 22, 1001, DOI: 10.1029/2001TC001305.

Heiskanen W.A. and Vening Meinesz F.A., 1958. The Earth and its Gravity Field. McGraw-Hill Inc., New York.

Heiskanen W.A. and Moritz H., 1967. Physical Geodesy. W.H. Freeman and Co., San Francisco and London.

Jin Y., McNutt M.K. and Zhu Y-S., 1996. Mapping the descent of Indian and Eurasian plates beneath the Tibetan Plateau from gravity anomalies. J. Geophys. Res., 101, 11275–11290.

Kiamehr R. and Gómez-Ortiz D., 2009. A new 3D Moho depth model for Iran based on the terrestrial gravity data and EGM2008 model. Geophys. Res. Abstr., 11, EGU2009-321-1, 2009.

Martinec Z., 1993. A Model of compensation of topographic masses. Surv. Geophys., 14, 525–535.

Martinec Z., 1994. The density contrast at the Mohorovičič discontinuity. Geophys. J. Int., 117, 539–544.

Martinec Z., 1998. Boundary-Value Problems for Gravimetric Determination of a Precise Geoid. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences No. 73, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany.

Moritz H., 1980. Advanced Physical Geodesy. Herbert Wichman, Karlsruhe, Germany.

Moritz H., 1990. The Figure of the Earth, Herbert Wichmann, Karlsruhe, Germany.

Mooney W.D., Laske G. and Masters T.G., 1998. CRUST 5.1: a global crustal model at 5×5 deg. J. Geophys. Res., 103, 727–747.

Nataf H.C. and Ricard Y., 1996. 3SMAC: An a priori tomographic model of the upper mantle based on geophysical modelling. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter., 95, 101–122.

Novák P. and Grafarend E.W., 2005. The ellipsoidal representation of the topographical potential and its vertical gradient. J. Geodesy, 78, 691–706.

Oldenburg D.W., 1974. The inversion and interpretation of gravity anomalies. Geophysics, 39, 526–536

Parker R.L., 1972. The rapid calculation of potential anomalies. Geophys J. R. Astron. Soc., 31, 447–455.

Pavlis N., Holmes S., Kenyon S., Schmidt D. and Trimmer R., 2005. A preliminary gravitational model to degree 2160. In: Jekeli C., Bastos L. and Fernandes J. (Eds.), Gravity, Geoid and Space Missions. International Association of Geodesy Symposia, 129, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 18–23.

Pavlis N., Factor K. and Holmes S.A., 2006. Terrain-Related Gravimetric Quantities Computed for the Next EGM. http://earth-info.nga.mil/GandG/wgs84/gravitymod/new_egm/EGM08_papers/NPavlis&al_S8_Revised111606.pdf.

Pavlis N.K., Holmes S.A., Kenyon S.C. and Factor J.K., 2008. An Earth Gravitational Model to Degree 2160: EGM2008. http://www.massentransporte.de/fileadmin/2kolloquium_muc/2008-10-08/Bosch/EGM2008.pdf.

Pratt J.H., 1855. On the attraction of the Himalaya Mountains and of the elevated regions beyond upon the plumb-line in India. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London B, 145, 53–100.

Reigber C., Jochmann H., Wünsch J., Petrovic S., Schwintzer P., Barthelmes F., Neumayer K.H., König R., Förste C., Balmino G., Biancale R., Lemoine J.M., Loyer S. and Perosanz F., 2004b. Earth gravity field and seasonal variability from CHAMP. In: Reigber C., Lühr H., Schwintzer P. and Wickert J. (Eds), Earth Observation with CHAMP - Results from Three Years in Orbit. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 25–30.

Rummel R., Rapp R.H., Sünkel H. and Tscherning C.C., 1988. Comparisons of Global Topographic-Isostatic Models to the Earth’s Observed Gravity Field. Report No. 388, Department of Geodetic Science and Surveying, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

Shin Y.H., Xu H., Braitenberg C., Fang J. and Wang Y., 2007. Moho undulation beneath Tibet from GRACE-integrated gravity data. Geophys. J. Int., 170, 971–985, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03457.x.

Shin Y.H., Choi K.S. and Xu H., 2006. Three-dimensional forward and inverse models for gravity fields based on the Fast Fourier Transform. Comput. Geosci., 32, 727–738, DOI: 10.1016/j.cageo.2005.10.002.

Sjöberg L.E., 1998a. The exterior Airy/Heiskanen topographic-isostatic gravity potential anomaly and the effect of analytical continuation in Stokes’ formula. J. Geodesy, 72, 654–662.

Sjöberg L.E., 1998b. On the Pratt and Airy models of isostatic geoid undulations. J. Geodyn., 26, 137–147.

Sjöberg L.E., 2009. Solving Vening Meinesz-Moritz inverse problem in isostasy. Geophys J. Int., 179, 1527–1536, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04397.x.

Sjöberg L.E. and Bagherbandi M., 2011. A method of estimating the Moho density contrast with a tentative application of EGM08 and CRUST2.0. Acta Geophys., 58, 502–525, DOI: 10.2478/s11600-011-0003-7.

Soller D.R., Ray R.D. and Brown R.D., 1982. A new global crustal thickness model. Tectonics, 1, 125–149.

Sünkel H., 1986. Global topographic-isostatic models. In: Sünkel H. (Ed.), Mathematical and Numerical Techniques in Physical Geodesy, Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences 7, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 417–462.

Tapley B., Ries J., Bettadpur S., Chambers D., Cheng M., Condi F., Gunter B., Kang Z., Nagel P., Pastor R., Pekker T., Poole S. and Wang F., 2005. GGM02-an improved Earth gravity field model from GRACE. J. Geodesy, 79, 467–478.

Tenzer R., Hamayun and Vajda P., 2009. Global maps of the CRUST2.0 components stripped gravity disturbances. J. Geophys. Res., 114, B05408.

Vening Meinesz F.A., 1931. Une nouvelle methode pour la reduction isostatique regionale de l’intensite de la pesanteur. Bull. Geod., 29, 33–51 (in French).

Vening Meinesz F.A., 1940. Fundamental tables for regional isostatic reduction of gravity value. Publ. Netherlands Acad. Sci., Sec. 1, 17(3), 1–44.

Vening Meinesz F.A., 1941. Tables for Regional and Local Isostatic Reduction (Airy System) for Gravity Values. Netherlands Geodetic Commission, Delft, The Netherlands.

Wild F. and Heck B., 2004. A comparison of different isostatic models applied to satellite gravity gradiometry. In: Jekeli C., Bastos L. and Fernandes J. (Eds.), Gravity, Geoid and Space Missions. International Association of Geodesy Symposia, 129, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 230–235.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bagherbandi, M., Sjöberg, L.E. Comparison of crustal thickness from two gravimetric-isostatic models and CRUST2.0. Stud Geophys Geod 55, 641–666 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11200-010-9030-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11200-010-9030-0