Abstract

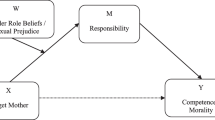

This study was designed to examine the influence of sex and gender role orientation on adoption of the ethic of care and on postconventional reasoning in married men and women, with and without children. Parental status was unrelated to gender role orientation in men but was associated with masculinity in women, such that women with children had lower masculinity scores. Adoption of an ethic of care in men was a function of gender role orientation, such that only androgynous men did not evidence lower caring scores when they had children. Caring scores in women were a function of both parental status and masculinity, such that women with children who were high in masculinity evidenced lower caring scores. Postconventional reasoning as assessed by P scores on three dilemmas from the Defining Issues Test (DIT) were only influenced by sex and age but not by gender role orientation. Postconventional reasoning as assessed by ratings of all postconventional statements (R scores) was influenced by both sex and gender role orientation; in men, masculinity and femininity interacted such that androgynous and undifferentiated men evidenced higher R scores when they had no children, but only androgynous men with children evidenced high R scores. In women, gender role orientation did not impact R scores and neither did parental status. Multiple regressions indicated that for women, the interaction of masculinity and femininity, and caring scores, accounted for a significant amount of the variance in R scores. In men, none of the variables entered the equation. The implications for both Gilligan’s and Bem’s theories are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Israeli students are generally in their 20s when they start their studies because the majority of 18 year olds of both genders are conscripted into the Israeli army; men serve a minimum of 3 years and women serve a minimum of 2 years. In addition, many of those who subsequently go to university do not do so immediately after leaving the army; they take a year off to travel, work, or do university preparation courses. Hence, Israeli undergraduate students are often married when they start their university studies, and the majority are married by the time they finish them. As well, Israeli society is highly family-oriented; it has the highest fertility rates among the developed countries (United Nations, 1997), almost no couples choose to remain childless, and it has the highest rate of IVF (in vitro fertilization) in the world (Eshre Capri Workshop Group, 2001). Hence, those students who are married and childless have generally chosen to temporarily delay having children.

Rest et al. (e.g., Rest et al., 1997; Rest, Narvaez, Thoma, & Bebeau, 1999) have recently started to use a new measure, called N2, which is essentially the same as P scores, with an adjustment that takes into account the standard deviations within the ratings assigned to the stages. It is computed as:

$$ P + 3 * {\left( {{\left[ {{\left( {{\text{Mean}}\,{\text{of}}\,{\text{Stage}}\,2 + 3} \right)} - {\left( {{\text{Mean}}\,{\text{of}}\,{\text{Stage}}\,5 + 6} \right)}} \right]}{\left[ {{\text{S}}{\text{.}}\,{\text{D}}.{\left( {{\text{stage}}2} \right)} + {\text{S}}{\text{.}}\,{\text{D}}{\text{.}}{\left( {{\text{stage}}3} \right)} + {\text{S}}{\text{.}}\,{\text{D}}{\text{.}}{\left( {{\text{stage}}5} \right)} + {\text{S}}{\text{.}}\,{\text{D}}{\text{.}}{\left( {{\text{stage}}6} \right)}} \right]}} \right)} $$They suggested using N2 because it predicts differences between criterion groups somewhat better than P. In our data, the correlation between P and N2 was r = .98, p < .001. But this new measure disadvantages women because, if they rate both post-conventional and conventional items the same way, which they would do if they use both justice concerns and care concerns, then the numerator in the adjustment to P is close to 0; this would not be a problem for men because they would rate the post-conventional items as higher. Consequently, the appropriate way of comparing postconventional reasoning in men and women is to compare actual ratings of postconventional items, which is what the R score represents.

References

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 155–162.

Bem, S. L. (1975). Gender role adaptability: One consequence of psychology androgyny. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 634–643.

Bem, S. L. (1977). On the utility of alternative procedures for assessing psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 45, 196–205.

Bem, S. L. (1984). Androgyny and gender schema theory: A conceptual and empirical integration. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 32, 179–226.

Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (1992). When partners become parents: The big life changes for couples. New York: Basic Books.

Cox, M. J., Owen, M. T., Lewis, J. M., & Henderson, V. K. (1989). Marriage, adult adjustment, and early parenting. Child Development, 60, 1015–1024.

Elson, M. (1984). Parenthood and the transformations of narcissism. In R. S. Cohen, B. J. Cohler, & S. H. Weissman (Eds.), Parenthood: A psychodynamic perspective (pp. 297–314). New York: Guilford.

Eshre Capri Workshop Group (2001). Social determinants of human reproduction. Human Reproduction, 16, 1518–1526.

Evans, R. G. (1984). Hostility and sex guilt: Perceptions of self and others as a function of gender and sex-role orientation. Sex Roles, 10, 207–215.

Feldman, S. S., Biringen, Z. C., & Nash, S. C. (1981). Fluctuations of gender-related self attributes as a function of stage of family life cycle. Developmental Psychology, 17, 24–35.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gilligan, C., & Attanucci, J. (1988). Two moral orientations: Gender differences and similarities. Merrill Palmer Quarterly, 34, 223–237.

Gilligan, C., & Wiggins, G. (1988). The origins of morality in early childhood relationships. In C. Gilligan, J. V. Ward, & J. M. Taylor (Eds.), Mapping the moral domain (pp. 111–138). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Glover, R. J. (2001). Discriminators of moral orientation: Gender role or personality? Journal of Adult Development, 8, 1–7.

Goldberg, W. A. (1988). Introduction: Perspectives on the transition to parenthood. In G. Y. Michaels & W. A. Goldberg (Eds.), The transition to parenthood: Current theory and research (pp. 1–20). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guttmann, D. (1985). The parental imperative. In J. Meacham (Ed.), The family and individual development (pp. 31–60). Basel: Karger.

Hosick, J. (1995). Moral development: The effects of gender and the transition to parenthood. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Jaffee, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2000). Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 703–726.

Jensen, L. C., McGhie, A. P., & Jensen, J. R. (1991). Do men’s and women’s world-views differ? Psychological Reports, 68, 312–314.

Karniol, R., Gabay, R., Ochion, Y., & Harari, Y. (1998). Is gender or gender-role orientation a better predictor of empathy in adolescence? Sex Roles, 39, 45–60.

Karniol, R., Grosz, E., & Schorr, I. (2003). Caring, gender role orientation, and volunteering. Sex Roles, 49, 11–19.

Kohlberg, L. (1958). The development of modes of moral thinking and choice in the years ten to sixteen. Doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago.

La Rossa, R., & La Rossa, M. M. (1981). Transition to parenthood: How infants change families. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Palkovitz, R. (1996). Parenting as a generator of adult development: Conceptual issues and implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13, 571–592.

Palkovitz, R., & Copes, M. (1988). Changes in attitudes, beliefs and expectations associated with the transition to parenthood. Marriage and Family Review, 12, 183–199.

Pratt, M., Golding, G., & Hunter, W. (1984). Does morality have a gender? Gender, gender role, and mora1 judgment relationships across the adult lifespan. Merrill Palmer Quarterly, 30, 321–340.

Pratt, M. W., Golding, G., Hunter, W., & Sampson, R. (1988). Gender differences in adult moral orientation. Journal of Personality, 56, 373–391.

Price, J. (1988). Motherhood: What it does to your mind. London: Pandora.

Rest, J. (1979). Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Rest, J. (1986). Moral development: Advances in research and theory. New York: Praeger.

Rest, J., Narvaez, D., Thoma, S. J., & Bebeau, M. J. (1999). DIT2: Devising and testing a revised instrument of moral judgment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 644–659.

Rest, J., Thoma, S. J., Narvaez, D., & Berbeau, M. J. (1997). Alchemy and beyond: Indexing the Defining Issues Test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 498–507.

Sirignano, S. W., & Lachman, M. E. (1985). Personality change during the transition to parenthood: The role of perceived infant temperament. Developmental Psychology, 21, 557–567.

Skoe, E. E. (1995). Gender role orientation and its relationship to the development of identity and moral thought. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 36, 235–245.

Skoe, E. E. A., Cumberland, A., Eisenberg, N., Hansen, K., & Perry, J. (2002). The influence of sex and gender-role identity on moral cognition and prosocial personality traits. Sex Roles, 46, 295–309.

Sochting, I., Skoe, E. E., & Marcia, J. E. (1994). Care-oriented moral reasoning and prosocial behavior: A question of gender or sex role orientation. Sex Roles, 31, 131–147.

Spence, J. T., & Helmreich, R. L. (1978). Masculinity and femininity: Their psychological dimensions, correlates, and antecedents. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Stander, V., & Jensen, L. (1993). The relationship of value orientation to moral cognition. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 24, 42–52.

Stimpson, D., Jensen, L., & Neff, W. (1992). Cross-cultural gender differences in preferences for a caring morality. Journal of Social Psychology, 132, 317–322.

Stimpson, D., Neff, W., Jensen, L., & Newby, T. (1991). The caring morality and gender differences. Psychological Reports, 60, 407–414.

Taylor, M. C., & Hall, J. A. (1982). Psychological androgyny: Theories, methods, and conclusions. Psychological Bulletin, 92, 347–366.

United Nations. (1997). Population Division of the United Nations Secretariat, World fertility patterns. (ST/ESA/SER.A/165). New York: United Nations Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karniol, R., Ekbali, G.BA. & Vashdi, D.R. The Impact of Parental Status and Gender Role Orientation on Caring and Postconventional Reasoning in Young Marrieds. Sex Roles 56, 341–350 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9173-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9173-1