Abstract

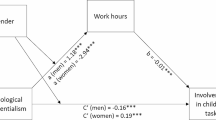

This study draws on Bem’s conceptualization (The lenses of gender: Transforming the debate on sexual inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993) of biological essentialism to explore fathers’ and mothers’ involvement in child care. The relationships between parental essentialist perceptions, gender ideology, fathers’ role attitudes, and various forms of involvement in child care were examined. Two hundred and nine couples with 6–36-month-old children completed extensive questionnaires. Analyses revealed that fathers’ essentialist perceptions predicted involvement in child care tasks and hours of care by the mother, whereas mothers’ essentialist perceptions predicted hours of care by the father. Parents’ attitudes toward the father’s role predicted involvement in child care tasks. Parents’ attitudes and perceptions contributed to involvement in child care even after the effects of the parents’ employment were controlled. The importance of examining various aspects of parents’ views, and distinguishing different forms of involvement in child care is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 888–918.

Aldous, J., Mulligan, G. M., & Bjarnason, T. (1998). Fathering over time: What makes the difference? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 809–820.

Barnett, R. C., & Baruch, G. B. (1987). Determinants of father’s participation in family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49, 29–40.

Becker, G. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Beitel, A. H., & Parke, R. D. (1998). Paternal involvement in infancy: The role of maternal and paternal attitudes. Journal of Family Psychology, 12, 268–288.

Bem, S. L. (1993). The lenses of gender: Transforming the debate on sexual inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bergen, E. (1991). The economic context of labor allocation: Implications for gender stratification. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 140–157.

Biernat, M., & Wortman, C. B. (1991). Sharing home responsibilities between professionally employed women and their husbands. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 844–860.

Coltrane, S. (1989). Household labor and the routine production of gender. Social Problems, 36, 473–490.

Coltrane, S. (1996). Family man: Fatherhood, housework, and gender equity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1208–1233.

Coverman, S. (1985). Explaining husbands’ participation in domestic labor. Sociological Quarterly, 26, 81–97.

Cowan, C., & Cowan, P. A. (1987). Man’s involvement in parenthood: Identifying the antecedents and understanding the barriers. In P. W. Berman & F. A. Pederson (Eds.), Men’s transitions to parenthood: Longitudinal studies of early family experiences (pp. 145–174). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Deutsch, F. M. (1999). Halving it all: How equally shared parenting works. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Deutsch, F. M., Lussier, J. B., & Servis, L. J. (1993). Husbands at home: Predictors of paternal participation in child care and housework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1154–1166.

Deutsch, F. M., & Saxon, S. E. (1998). Traditional ideologies, nontraditional lives. Sex Roles, 38, 331–362.

Gaunt, R. (2005). The role of value priorities in paternal and maternal involvement in child care. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 643–655.

Glass, J. (1998). Gender liberation, economic squeeze, or fear of strangers: Why fathers provide infant care in dual-earner families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 821–834.

Greenstein, T. N. (1996). Husbands’ participation in domestic labor: Interactive effects of wives’ and husbands’ gender ideologies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 585–595.

Haslam, N., Rothschild, L., & Ernst, D. (2000). Essentialist beliefs about social categories. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 113–127.

Hochschild, A. R. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Avon.

Israel Women’s Network (2003). Women in Israel: Compendium of data and information. Jerusalem: Israel Women’s Network.

Lamb, M. E. (1987). The father’s role: Cross-cultural perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Levy-Shiff, R., & Israelashvili, R. (1988). Antecedents of fathering: Some further exploration. Developmental Psychology, 24, 434–440.

Leyens, J. P., Paladino, P. M., Rodriguez, R. T., Vaes, J., Demoulin, S., Rodriguez, A. P. et al. (2000). The emotional side of prejudice: The role of secondary emotions. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 186–197.

Marsiglio, W. (1991). Paternal engagement activities with minor children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 973–986.

McBride, B. A., Schoppe, S. J., & Rane, T. R. (2002). Child characteristics, parenting stress, and parental involvement: Fathers versus mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 998–1011.

McHale, S. M., & Huston, T. L (1984). Men and women as parents: Sex role orientations, employment, and parental roles with infants. Child Development, 55, 1349–1361.

Medin, D. L. (1989). Concepts and conceptual structure. American Psychologist, 44, 1469–1481.

Medin, D. L., & Ortony, A. (1989). Psychological essentialism. In S. Vosnaidou & A. Ortony (Eds.), Similarity and analogical reasoning (pp. 179–195). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2000). Factors associated with fathers’ caregiving activities and sensitivity with young children. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 200–219.

Pleck, J. H. (1981). The myth of masculinity. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Pleck, J. H. (1997). Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (3rd ed., pp. 66–103). New York: Wiley.

Pleck, J. H., Lamb, M. E., & Levine, J. A. (1986). Epilog: Facilitating future change in men’s family roles. In R. A Lewis & M. Sussman (Eds.), Men’s changing roles in the family (pp. 11–16). New York: Haworth.

Pleck, J. H., & Masciadrelli, B. P. (2003). Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 222–271). New York: Wiley.

Rothbart, M., & Taylor, M. (1992). Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds? In G. Semin & F. Fiedler (Eds.), Language, interaction and social cognition (pp. 11–36). London, UK: Sage.

Thompson, E. H., & Pleck, J. H. (1986). The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 531–543.

Thompson, L., & Walker, A. J. (1989). Gender in families: Women and men in marriage, work, and parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51, 845–871.

Van Dijk, L., & Siegers, J. J. (1996). The division of child care among mothers, fathers, and nonparental care providers in Dutch two-parent families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 1018–1028.

Volling, B. L., & Belsky, J. (1991). Multiple determinants of father involvement during infancy in dual-earner and single-earner families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 461–474.

Yeung, J. W., Sandberg, J. F., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Children’s time with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 136–154.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by Grant 4939 from The Israel Foundations Trustees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaunt, R. Biological Essentialism, Gender Ideologies, and Role Attitudes: What Determines Parents’ Involvement in Child Care. Sex Roles 55, 523–533 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9105-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9105-0