Abstract

To describe sexual functioning/satisfaction and relational satisfaction of patients with stroke who received sexual counselling during their rehabilitation 1–5 years thereafter. All adult patients with stroke admitted to one Dutch Rehabilitation Centre between January 2010 and January 2014 with at least two consultations with a sexologist were invited to participate in this cross-sectional survey study. Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire on sexual functioning, relational satisfaction (Maudsley Marital Questionnaire, 0–80; low–high dissatisfaction), health-related quality of life (HRQoL) short-form12 (SF-12) mental and physical component scale (MCS and PCS; 0–100, low–high HRQoL) and mood Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS, 0–21 low–high depression/anxiety). Descriptive statistics were used for sexual functioning/satisfaction and relational satisfaction. Spearmans’s correlation analysis (rs) analyzed the relationships between sexual satisfaction, relational satisfaction, PCS, MCS, depression and anxiety. Of 296 eligible patients, 62 (21%) completed the questionnaires. Mean age 55.4 (SD11.0) years, time-since-stroke 3.5 (SD3.6) years, 33 (53%) were male and 18 (29%) were single. Being sexually (very) unsatisfied was reported by 31 (54%) responders, with 63% being male and 44% female. Median MMQ-score relational satisfaction was 12.0 (IQR 4.25–23.25). A moderate correlation was present between sexual and relational satisfaction (rs = 0.35, p = 0.02). In male respondents relational satisfaction was highly correlated with lower levels of anxiety (rs = 0.54, p = 0.01) and depressive symptoms (rs = 0.71, p = 0.00). Patients with stroke who received sexual counselling during their rehabilitation treatment experience high relational satisfaction in the long term after stroke, despite their problems in sexual functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stroke is a major cause of disability, with a prevalence of about two percent in the Western adult population [1]. Despite improvements in the acute medical treatment of stroke its consequences on important functional and life domains is considerable: speech problems, physical impairments, fatigue, impaired stress tolerance and concentration and memory deficits often occur [2].

But also sexual health may be affected by stroke. Hypogonadism (testosterone deficiency), loss of libido and anxiety may be present and have a potential negative influence on sexual functioning [3]. Sexual problems after stroke are common; up to 75% of male patients with stroke report erectile dysfunction and up to 77% of females report difficulties with vaginal lubrication [3]. Sexual rehabilitation interventions have proven to result in improved sexual satisfaction, sexual activity frequency and erectile function [4].

In some specialized centers for medical rehabilitation in The Netherlands, sexual and relational counselling by a sexologist is part of the stroke rehabilitation program [5]. The goal of sexual and relational counselling in rehabilitation is to achieve a better sexual health status and improve relational functioning after stroke. Relatively little is known about the long term outcomes of patients who receive sexual counselling during their rehabilitation treatment. The purpose of the present cross-sectional study was to describe the long term sexual and relational functioning in patients with stroke who received sexual counselling as a part of their rehabilitation program.

Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional questionnaire study among patients with stroke was conducted at Basalt Rehabilitation Centre, The Hague in the Netherlands. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Leiden University Medical Centre [P15.229]. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Study Population

All adult patients with stroke who were admitted for either inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation treatment between January 2010 and December 2014 were identified. Patients who consulted the sexologist more than once during their rehabilitation period were approached by letter and telephone to participate in the study. Both patients with and without a partner were invited to participate. If patients agreed to participate, a questionnaire in a pre-stamped envelope was sent to them via postal mail. Participants who completed the questionnaire received a gift certificate of €10.

Sexual and Relational Counseling in Stroke Rehabilitation

The relational and sexual counselling provided in the rehabilitation center has a strong focus on the intimate relationship and sexual health. Counselling is mostly provided to individual patients and when needed and/or appropriate, together with their partners. In counseling the classification of disability-related sexual health problems that is widely applied within rehabilitation sexology in the Netherlands and has been developed by Pieters et al. [6] is used.

The classification comprises six areas of sexual difficulties, often experienced by patients: (a) problems with sexual functions; (b) the sexual subjective experience has changed; (c) intimacy in a relationship is disturbed; (d) practical difficulties which are kill joys for sexual pleasure; (e) difficulties adjusting to the limitations in sexual activities caused by a chronic illness of physical limitations; (f) difficulties that young people with chronic physical problems have to incorporate courtship, dating, and sexuality into their lives.

The contents and aims of the counseling are based on adaptation, compensation and acceptance as three important principles of rehabilitation medicine:

-

(1)

Adaptation; each individual facing a chronic condition or a health problem is confronted with major adaptations in often the most basic areas of life of which participation in intimate relationships is a very important one. Counselling supports patients in their journey to adaptation in intimate relationships, e.g. addressing the fear of the re-occurrence of a stroke while being intimate.

-

(2)

Compensation strategies and materials; often patients and their partners are confronted with practical problems in their intimate relationship e.g. if they are not able to make sufficient adaptations to be satisfied with their sexual health and functioning. During the counselling period compensation strategies and materials are introduced and tested. Examples are: strategies to improve self-esteem and body-image, but also vibrators, PDE5-inhibitors to enhance penile erection, incontinence materials and supporting cushions for positioning. The overarching treatment goal is to make sexual behaviors and experiences possible and often more satisfying.

-

(3)

Acceptance and emotional consequences of major health incidents; health issues often lead to a great sense of loss and grief with difficulties in accepting the consequences of these health issues. In counselling the consequences of health problems in the intimate relationships and sexual health of our patients is discussed as an important prerequisite for working on the first 2 principles.

The sexual and relational counselling was provided by two sexologists, who are both registered/certified as clinical sex therapists at the Dutch Scientific Society of Sexology. One sexologist, JB (working experience as a sexologist for 30 years) holds a master in Psychology and completed an additional post-master education as a sexologist. The other sexologist, EdK (working experience as a sexologist for 14 years) holds a bachelor in social work, a post-bachelor in marriage- and family therapy and completed an additional post-master education as a sexologist.

Assessments

Age, diagnosis and time since stroke were extracted from the medical record. All other data were collected from the questionnaires.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Patients were asked to report sex, relational status (having a partner or not) and educational level (Low: up to and including lower technical and vocational training; Medium: up to and including secondary technical and vocational training; High: up to and including higher technical and vocational training and university).

Sexual Functioning

To assess sexual functioning in both patients with and without a partner, the Eleven Questions about Sexual Functioning (ESF men and ESF woman) was used [7]. The ESF identifies the duration and frequency of sexual problems due to a health condition and covers four aspects of sexual functioning (scored as monthly frequency on a 7-point Likert scale never − several times per day) having: sexual fantasies, solo sex, a desire for sexual contact, actual sexual contact.

In addition the ESF assess; reduced quality of stiffness/lubrication, reduced duration of stiffness/lubrication, actually having an orgasm, having a postponed orgasm, having a premature orgasm and experiencing pain in genitals covered as monthly frequency on a 5-point Likert scale (never − every time). The ESF also comprises a general satisfaction score on a 5-point Likert scale; very dissatisfied − very satisfied.

The ESF is not validated and no reference data are available.

Relational Satisfaction

For patients with a partner, the subscale relation satisfaction of the Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ-rs) was used to assess the relational satisfaction [8]. The MMQ is a standardized and validated questionnaire with 20 items on a nine-point Likert-scale (0–8; no − great dissatisfaction). This scale ranges from 0 to 80, where higher scores are indicative of greater dissatisfaction. The MMQ is not specifically validated for patients with stroke. A score of > 25 indicates that patients experience limitations, a score of > 36 indicates severe limitation.

Health Related Quality of Life

The Short Form-12 (SF-12) is a brief and reliable instrument for quality of life [9]. Two subscales can be derived from the SF-12: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS). The PCS and MCS scores have a range of 0 to 100 with a higher score indicating a better health status. The general population scores 50 on average with a standard deviation of 10.

Mood

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a validated self-assessment scale that indicates if a patient suffers from depressive and anxiety symptoms [10]. The 7 questions relating to anxiety are indicated by an ‘A’ while the 7 questions relating to depression are shown by a ‘D’. HADS items can be scored 0–3 adding up to 0–21 for either anxiety or depression. A HADS score > 7 on anxiety or depression is an indicator of clinical symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Statistical Analyses

The data of the pen-and-paper questionnaires were entered in a Microsoft Office Access 2010 database. Subsequently the Access-database was imported in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS statistics, Version 23) for further analysis.

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants as well as measures of sexual and relational functioning, quality of life (SF-12) and emotional functioning (HADS-A and HADS-D) were analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR) or numbers and percentages), where appropriate.

Spearman correlation coefficients (p < 0.05) were used to analyze the strength of the linear relationship between sexual dissatisfaction (ESF question 11; 1–5 equaling very unsatisfied – very satisfied) and relational functioning MMQ-rs with the other PROMs (SF-12-PCS, SF-12-MCS, HADS-A, HADS-D) included in the study.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants. Of 296 eligible patients, 63 (21%) gave informed consent of whom 62 completed the questionnaires. Mean (SD) age was 55.4 (11.0) years and median (IQR) time since stroke was 2.6 (1.5–4.7) years (Table 1). Approximately half of the respondents (n = 33, 53%) were male and one-third (n = 18, 29%) were single. Educational levels were roughly even distributed: 13 (37%) respondents low, 14 (27%) medium and 12 (34%) high (2% unknown).

Sexual Functioning

Table 2 shows the answers to the eleven questions on sexual functioning of the patients with stroke in this study. Men reported more sexual daydreams. No major differences between men and women were found in masturbation frequencies, desire for sexual contact and actual sexual contact itself. Of men, 80% reported more or less problems with erectile function and 93% reported problems with the duration of the erection. In female, 52% reported more or less problems during the preceding month with the quantity of lubrication and 35% reported on problems with the duration of lubrication. During intercourse, 17% of men always had an orgasm versus 39% in female. The occurrence in the preceding month of one or more accelerated orgasms were reported by 55% of the men and 9% of the women, delayed orgasms by 57% and 43% respectively. The occurrence in the preceding month of one or more phases of discomfort in the genital area was reported by 39% of male and 35% of female responding patients. Of male patients, 63% was (very) unsatisfied with their sex life versus 44% in women.

Relational Functioning and Measures of QoL, Well-Being and Mood

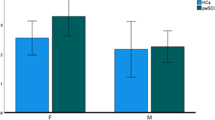

Table 3 shows the median MMQ-score for relational satisfaction was 12.0 (IQR 4.3–23.5), indicating that in general no severe relational problems were present, since this is well below the cut off of 25.0 on the 0–80 scale. Again, no differences between male and females were found (independent samples Mann Whitney U test). Mental health reported in the SF-12 was lower than the normal population (mean 45.6, SD 10.3). The physical component reported in the SF-12 was more than 1 SD below the general population (mean 38.2, SD 9.4). Regarding the HADS; for anxiety the mean score was 6.6 (SD4.3) and 21 (34%) patients scored above the cut off level of 7. For depression the mean score was 7.0 (SD 4.0) and 25 (40%) scored above the cut off level of 7.

Correlations Between Sexual Satisfaction, Respectively Relational Satisfaction and Other Outcomes

Table 4 shows the relationships of sexual functioning (ESF) and relational satisfaction (MMQ-rs) with quality of life and mood. Irrespective of sex, moderate positive correlations were found between high relational satisfaction and higher sexual satisfaction (rs = 0.35, p = 0.02), higher mental HRQoL (rs = 0.34, p = 0.03), less anxiety (rs = 0.34, p = 0.02) and less depressive symptoms (rs = 0.36, p = 0.02). In male respondents moderate positive correlations were found between high sexual satisfaction and less depressive symptoms (rs = 0.35, p = 0.05). In addition in male respondents high positive correlations were found between high relational satisfaction and less anxiety (rs = 0.54, p = 0.01) and less depressive symptoms (rs = 0.71, p = 0.00). In female respondents moderate positive correlations were found between high sexual satisfaction and higher relational satisfaction rs = 0.46 (0.03), respectively higher mental HRQoL (rs = 0.55, p = 0.01).

Discussion

Our study among study patients with stroke who received sexual counselling showed high relational satisfaction in the long term after stroke. Despite substantial problems in sexual functioning and a substantial proportion of patients who indicated that that they were not satisfied about their sex life (i.e. 63% of the men and 44% of the women). Moreover, relational and sexual satisfaction are significantly related to each other. Although our study had a number of limitations, it shows that on the longer term after stroke, patients may still report sexual dysfunction and reduced satisfaction with sexual life, despite sexual counselling in the past. This is an interesting finding, as previous studies on sexuality in patients following stroke did not include patients who had sexual counselling as part of their rehabilitation treatment specifically.

In this study, erectile and lubrication dysfunction are common and problems with orgasms occur frequently. Besides, about one third of patients suffers from some form of discomfort in the genital area. This occurrence of sexual dysfunction after stroke is not unexpected and in concordance with literature [11].

Our study population had relatively high depression [mean HADS-D 7.0 (SD4.0)] and anxiety [mean HADS-A 6.6 (SD4.3)] scores for patients after a stroke. However, our numbers of patients with a possible depression (40%) were comparable with rehabilitation cohorts with a similar follow-up duration [12]. Nevertheless, the relationships between sexual functioning, relational functioning, post-stroke depression and anxiety are similar to the relationships observed in other studies [13, 14].

An important limitation of this study is the low response rate, which potentially introduces a selection bias and threatens the generalizability of our results. One might postulate that questionnaires were filled in more often by patients that encounter sexual dysfunction. In addition, patients only completed the questionnaire once therefore it is not possible to infer changes over time or infer causal relationships from our data. Moreover, the ESF as an outcome for sexual functioning was not validated to be used for the current purpose in the study population. Another limitation is the conduct of the study in only one, western European country. It is generally known that there are large cultural differences regarding sexuality, as well as differences between countries in the role of sex counselling in rehabilitation. Therefore, it is difficult to estimate to what extent the findings translate cross-culturally.

Patients with stroke that received sexual and relational counselling during their rehabilitation treatment perceive high relational satisfaction. Unfortunately, despite early sexual counselling patients still report sexual dysfunction and reduced satisfaction with sexual life. Our findings could imply that regular follow-up of sexual functioning and satisfaction with sexual life is useful after stroke rehabilitation, even after sexual counselling, since stroke-related problems may persist or arise during each patient’s / couple’s lifespan. However, given the relatively low response in our study, it is plausible that a specific subgroup of patients would be interested in such a follow-up, with the question arising when, how and by whom patients could best be approached. In addition, consensus must be reached on the contents of follow-up assessment, including validated outcome measures and more research using structured treatment programs for sexual / relational counselling during stroke rehabilitation with follow-up assessment using validated outcomes on fixed time points are needed to improve insight in the added value of counselling treatment.

References

WHO Health topics: Stroke, Cerebrovascular accident. https://www.who.int/topics/cerebrovascular_accident/en/ (2019)

Geyh, S., Cieza, A., Schouten, J., Dickson, H., Frommelt, P., Omar, Z., Kostanjsek, N., Ring, H., Stucki, G.: ICF core sets for stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. 44(Suppl), 135–141 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/16501960410016776

Grenier-Genest, A., Gerard, M., Courtois, F.: Stroke and sexual functioning: a literature review. NeuroRehabilitation 41(2), 293–315 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-001481

Dusenbury, W., Palm Johansen, P., Mosack, V., Steinke, E.E.: Determinants of sexual function and dysfunction in men and women with stroke: a systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12969

Kruijver, E., Bender, J., Meesters, J.: Yes, sex can be rehabilitated! [Originally in Dutch with English Summary: ‘Ja! Seks kan gerevalideerd worden!’]. Dutch J. Sexol. 39(3), 96–100 (2015)

Pieters, R., Kedde, H., Bender, J.: Training rehabilitation teams in sexual health care: a description and evaluation of a multidisciplinary intervention. Disabil. Rehabil. 40(6), 732–739 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1271026

Vroege, J.A.: Eleven Questions on Sexual Functioning (ESF): An Extension of the Questionnaire for Screening Sexual Dysfunctions (QSF), 1st edn. Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Centre Leiden, Leiden (1998)

Joseph, O., Alfons, V., Rob, S.: Further validation of the Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ). Psychol. Health Med. 12(3), 346–352 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600855481

Gandek, B., Ware, J.E., Aaronson, N.K., Apolone, G., Bjorner, J.B., Brazier, J.E., Bullinger, M., Kaasa, S., Leplege, A., Prieto, L., Sullivan, M.: Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J. Clin. Epidemiol 51(11), 1171–1178 (1998)

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A.A., Haug, T.T., Neckelmann, D.: The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 52(2), 69–77 (2002)

Rosenbaum, T., Vadas, D., Kalichman, L.: Sexual function in post-stroke patients: considerations for rehabilitation. J. Sex Med. 11(1), 15–21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12343

Hackett, M.L., Pickles, K.: Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Stroke 9(8), 1017–1025 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12357

Wright, F., Wu, S., Chun, H.Y., Mead, G.: Factors associated with poststroke anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke Res. Treat. 2017, 2124743 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2124743

Das, J., G, K.R.: Post stroke depression: the sequelae of cerebral stroke. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 90, 104–114 (2018). 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.005

Acknowledgements

We like to thank all the respondents who participated in the study and Cedric Kromme for supporting data management.

Funding

This gift certificates for study participants were funded by the Dutch Fund for Stimulation & Development of Sexology and the Dutch Scientific Association of Sexology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meesters, J.J.L., van de Ven, D.P.H.W., Kruijver, E. et al. Counselled Patients with Stroke Still Experience Sexual and Relational Problems 1–5 Years After Stroke Rehabilitation. Sex Disabil 38, 533–545 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09632-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09632-5