Abstract

Despite the successful adoption of mobile money in sub-Saharan Africa, there is limited empirical evidence on how mobile money interacts with traditional financial services and the implications of this interaction for firm performance. In this paper, we investigate the effects of mobile money use and access to traditional financial services on labour productivity and test whether mobile money can accentuate the impact of traditional financial services on productivity. Using firm-level data from the World Bank Enterprise Survey across 14 sub-Saharan African countries, we find a significant effect of access to traditional financial services on firm labour productivity but no robust significant direct effect of mobile money use on labour productivity. However, when access to traditional financial services, particularly access to bank capital, is combined with mobile money, there is a productivity improvement. We find similar evidence in the sample of small and medium-sized enterprises. The productivity gain from combining mobile money use with traditional financial service is also found within firms from East Africa and especially firms from other regions where mobile money is emerging, but uptake is relatively low. Overall, the evidence suggests that mobile money can heighten the effects of traditional finance, and we attribute this effect to a reduction in transaction costs. The findings in this paper support that both mobile money and traditional financial services should be promoted at the firm level.

Plain English Summary

Mobile money heightens the effect of traditional finance on firm performance. Based on firm-level data across 14 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, we find that mobile money has no statistically significant effect on labour productivity, but when it is used in combination with traditional financial services such as bank capital and accounts, then there is a productivity improvement, including in countries where mobile money adoption is relatively low. The evidence implies that mobile money can help formal firms derive maximum benefits from traditional financial services due to its potential to reduce transaction costs. Therefore, the use of both mobile money and traditional financial services should be encouraged among formal firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The extant literature suggests that financial development is critical for transaction cost reduction, risk management, the allocation of productive resources to potential entrepreneurs and consequently productivity enhancement (King & Levine, 1993; Levine et al., 2000).Footnote 1 At the firm level, access to financial services such as bank credit facilitates the entry of small firms and improves firm growth and productivity (Fafchamps & Schündeln, 2013; Girma & Vencappa, 2015). A growing body of literature also shows that financial inclusion is equally important for firm performance (Chauvet & Jacolin, 2017; Lee et al., 2020). In sub-Saharan Africa, however, the underdevelopment of the financial infrastructure limits the provision of financial services to a large segment of the population (Allen et al., 2014; Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018; Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2015). The existence of a few bank branches and the overconcentration of bank branches in urban centres (Beck et al., 2009) hinder financial transactions and make transactions especially in geographically dispersed regions costly posing a major challenge to firms’ operations and expansion.

The advent of mobile money, a low-cost financial innovation to conduct financial transactions via mobile phones, has therefore received attention in the literature due to its potential to leverage telecommunication infrastructure to extend financial services to both the banked and unbanked segments of the society.Footnote 2 Mobile money offers at least two advantages to firms with significant implications for labour productivity. First, mobile money can help reduce financial transaction costs (Jack & Suri, 2014) which may enable firms to channel more of their limited financial resources towards investment and business expansion (Islam et al., 2018). Second, mobile money can facilitate access to trade credit and loans (Beck et al., 2018; Gosavi, 2018), thereby improving the availability of funds for business operations. The successful deployment of mobile money in sub-Saharan Africa coupled with the leading role played by mobile network operators (MNOs) in the delivery of mobile money services (Donovan, 2015; Maurer, 2012; Pelletier et al., 2020; Sy et al., 2019) raises an important policy question about whether mobile money complements existing traditional financial services in relation to firm performance such as labour productivity. Empirical evidence in this regard is limited as most studies focused on the firm-level implications of either traditional financial services or mobile money (Beck & Demirguc-kunt, 2006; Islam & Muzi, 2020; Islam et al., 2018) without testing for possible complementarities. There is evidence showing that mobile money and traditional financial services coexist (Gosavi, 2015),Footnote 3 but we do not know how the interplay between these two financial services affects firm productivity.

This paper examines the effects of mobile money use and access to traditional bank services such as account ownership and bank capital on firm labour productivity. Most importantly, this paper accounts for the interaction between mobile money and traditional financial services. We argue that in the face of financial frictions, mobile money use can accentuate the effect of traditional financial services on labour productivity by reducing the extra burden that comes with financial transaction costs. For our analysis, we employ the World Bank Enterprise Surveys across 14 sub-Saharan African countries for which information about mobile money use for transactions is available. We use as our main performance indicator labour productivity which is measured as value added per worker following the approach by Aterido and Hallward-Driemeier (2011). The paper focuses on labour productivity given that it is a major contributing factor to the growth of firms and consequently economic development in emerging economies (Motta, 2020).

Our findings can be summarised as follows. First, we find evidence that points to a positive significant effect of access to traditional finance on labour productivity, confirming previous findings in the literature. Second, we find that mobile money has no robust statistically significant direct effect on labour productivity, but when bank capital and bank account are combined with mobile money, then there is a productivity improvement. We find similar evidence in the sub-sample of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and more robust evidence in the sub-sample of countries outside East Africa where mobile money adoption is low. In the sample of the three East African countries with the highest mobile money adoption, we find that mobile money use alone can have a positive direct effect on productivity and more so when it is combined with access to bank capital. Overall, the findings in this paper suggest that mobile money can accentuate the effects of access to traditional finance, and therefore, at the policy front, both mobile money and traditional financial services, especially access to bank capital, should be promoted at the firm level.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents the review of related literature, Section 3 discusses the mechanisms of the interaction between mobile money and traditional finance, Section 4 provides the data description, Section 5 discusses the empirical strategy, Section 6 presents the results and Section 7 offers the main conclusion of the study.

2 Related literature

2.1 Access to traditional financial services and firm performance

The extant literature shows that access to finance is a major obstacle to firm performance in developing countries (Beck & Demirguc-kunt, 2006; Beck et al., 2005; Sleuwaegen & Goedhuys, 2002). The presence of financial constraints in these regions implies that firms have limited financial resources to use for their day-to-day operations and to meet their investment needs. Traditional financial services, such as bank loans, therefore, remain a useful source of external finance available to firms that can be leveraged to relax the burden of financial constraints leading to firm performance.

Aghion et al. (2007) investigate the effect of financial development on the entry and the post-entry performance of firms based on firm-level data composing of 16 industrialised and emerging economies. The study reveals that access to finance has a significant effect on the entry and post-entry performance of firms especially among SMEs and in sectors that are dependent on external finance. Fafchamps and Schündeln (2013) examine the relationship between local financial development and firm performance. The study finds evidence suggesting that local financial development affects firm performance significantly. The study reveals that bank availability is positively associated with faster firm growth, and firms located in sectors with a bank nearby are more likely to invest, hire workers, reduce labour costs and increase output per worker. Also, Girma and Vencappa (2015) find that access to credit from banks and non-bank financial institutions has a positive influence on firms’ productivity growth. More recently, Motta (2020) inter alia provides evidence suggesting that SMEs with access to bank loans achieve higher productivity than SMEs that applied for bank loans but were rejected. This finding is consistent with a study by Boermans and Willebrands (2018) which reveals that financial constraint is an inhibiting factor to labour productivity and entrepreneurship in Tanzania. Similarly, Bokpin et al. (2018) investigate the effect of access to credit on labour productivity among manufacturing firms in sub-Saharan Africa. The study finds evidence indicating that access to credit or overdraft facilities affects labour productivity positively.

The extant literature shows that access to traditional financial services matters for firm performance. However, there is evidence to suggest that the financial system in sub-Saharan Africa is underdeveloped (Allen et al., 2012). Consequently, there are fewer bank branches, and a significant proportion of the adult population are without bank accounts (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018). This makes financial transactions costly especially in underserved regions posing an additional challenge to firms. This paper goes beyond the extant literature that links firm performance to traditional financial services by highlighting the contribution of mobile money in this regard.

2.2 Mobile money and its implications for firm performance

Mobile money has become an important financial innovation in sub-Saharan Africa where mobile money transactions and account ownership continue to grow exponentially (GSMA, 2017). Given that mobile money is an SMS-based money transfer and monetary storage system, it is more readily accessible to mobile phone users. Moreover, mobile money agent outlets which serve as centres of mobile money registration, cash-in and cash-out services are widespread compared to bank branches (Suri, 2017). The convenience associated with mobile money transactions in the face of limited banking infrastructure (Mbiti & Weil, 2016) makes mobile money services favourable to consumers. Mobile money can be used by firms to receive or make payments from customers and suppliers respectively. Also, mobile money enables firms to conduct financial transactions such as the payment of utility bills or payment of salaries to employees.

The advent of mobile money offers several advantages to firms. First, the use of mobile money can help firms reduce transaction costs. This can translate into improved liquidity at the firm level and more investments. A study conducted by Jack and Suri (2014) in Kenya shows that mobile money adoption leads to a reduction in transaction costs. There is also evidence to suggest that the use of mobile money by employers to pay salaries leads to significant cost savings (Blumenstock et al., 2015). Islam et al. (2018) using cross-country data for three East African countries find a positive relationship between mobile money use and firm-level investment. Islam et al. (2018) attribute this effect to the reduction in transaction costs, creditworthiness and the liquidity associated with mobile money use. The study also finds that small and medium-sized enterprises tend to benefit more from mobile money adoption. In a recent study, Islam and Muzi (2020) find that the effect of mobile money on firm-level investment is driven by female-owned businesses compared to male-owned firms.

Second, the literature suggests that the use of mobile money facilitates access to external finance. Beck et al. (2018) find that mobile money adoption is associated with entrepreneurs’ access to trade credit in Kenya. In a related study, Gosavi (2018) shows that mobile money facilitates access to finance and firms that use mobile money for transactions are more productive in the East African region. Dalton et al. (2019) examine the effect of Lipa Na M-PESA, a prototype of mobile money, on access to finance among Kenyan firms. The study shows that firms that use Lipa Na M-PESA have better access to external finance in the form of mobile loans compared to non-adopters. This effect is however stronger for small firms. The underlying mechanism is that Lipa Na M-PESA enables the MNO (Safaricom) to monitor the transactions of adopting firms, track their creditworthiness and offer loans to firms with a higher chance of repayment (Dalton et al., 2019).

Third, mobile money adoption through its effect on transaction costs, investment and credit access can contribute to firm performance. Recent studies suggest that mobile money adoption may be instrumental in engendering firm performance (Asamoah et al., 2020; Talom & Tengeh, 2020). Asamoah et al. (2020) find that entrepreneurs’ mobile money capabilities defined as the skills required to conduct mobile money transactions have a positive significant association with firm growth. An empirical study in Cameroon also shows that mobile money adoption affects the business turnover of SMEs (Talom & Tengeh, 2020).

One major shortfall in the literature is that most studies focus mainly on the direct effect of traditional financial services on firm performance. A few studies that attempt to unravel the firm-level implications of mobile money for firm performance also focus on its direct effects ignoring the possible interaction that may occur between mobile money and traditional financial services and how this can be beneficial to firms. In this paper, we pay particular attention to how the coexistence of traditional financial services and mobile money at the firm level can influence firm-level productivity.

3 Why would interaction between mobile money and traditional finance matter for firm performance?

In sub-Saharan Africa, mobile money is mainly driven by mobile network operators (MNOs) although banks also provide mobile money services as an additional delivery channel and, in most cases, such services are offered to consumers in collaboration with MNOs. Pelletier et al. (2020) find that in emerging markets where there are weak legal rights and limited credit information, MNOs are more likely to launch mobile money services compared to banks. The study notes that the high compliance costs associated with know your customer (KYC) obligations and customer risk assessments in countries with weak institutions often disincentivise banks from providing additional services outside their core business activities. Consequently, banks provide services that revolve around their fixed costs such as branch networks. The study argues that MNOs have a comparative advantage in providing mobile money because they depend on their existing telecommunication infrastructure and distribution networks to offer such services at relatively low costs. Also, MNOs have access to the transaction histories of telecommunication consumers that can be leveraged to compensate for the lack of credit information in developing countries.

However, Pelletier et al. (2020) find that it is when mobile money is provided through a banking channel that it yields greater spillover effects on the economy. Nonetheless, recent financial inclusion policies aimed at promoting the interoperability of financial services that have led to some collaboration between mobile money providers and banks in the provision of mobile money services (GSMA, 2015). Interoperability enables mobile money users to transfer money from bank accounts into mobile money wallets and vice versa. These bilateral and multilateral arrangements between MNOs and banks, for example, are evident in Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania and Côte d’Ivoire (Arabehety et al., 2016).

Given that banks are less likely to launch mobile money services, one may argue that MNOs will eventually erode the advantage of banks in the provision of financial services. The literature suggests this is unlikely because banks have a comparative advantage in the provision of certain financial services such as wholesale payments (Kahn & Roberds, 2009) while mobile money is more advantageous in high volume but low-value transactions (Donovan, 2015; Ghunaim, 2020; Pelletier et al., 2020).

The delivery of mobile money by either MNOs or banks or both suggests that an additional financial service will become available to firms that could potentially enhance the effect of traditional financial services on firm performance. The availability of both mobile money and traditional financial services will enable firms to derive maximum benefit from financial transactions especially given that firms may have the opportunity to employ the financial service that is more beneficial. Transaction costs and consumer choice theories suggest that during transactions, rational agents are more likely to choose the medium of exchange that is associated with the minimum costs (Baumol, 1952; White, 1975; Whitesell, 1989, 1992). Transaction costs, however, vary depending on the payment mechanism and the size or value of transactions (Grüschow et al., 2016; Whitesell, 1989).

McKay and Pickens (2010) find that low-value transactions (transactions that involve small amounts) using financial innovations including mobile money are relatively cheaper compared to traditional banking channels. Conversely, bank transactions are relatively cheaper when transaction values are high. The study reveals that a low-value deposit of USD23 via a branchless banking provider is 38% cheaper compared to banks. However, a high-value transaction via branchless banking providers is estimated to be 45% more expensive than the use of banks for the same transaction.Footnote 4 Essentially, mobile money benefits firms by enabling them to conduct low-value transactions at reduced costs leading to significant cost savings. The potential cost savings associated with the adoption of mobile money in addition to traditional financial services has an important implication for firm performance. In the face of limited financial resources, carrying out transactions at reduced costs implies that additional financial resources will become available to meet the liquidity or investment needs of firms. In this case, we expect that mobile money use for transactions will accentuate the effect of traditional financial services on firm performance through a reduction in transaction costs. We anticipate that this effect will be pronounced among smaller firms given that such firms are more likely to be engaged in low-value transactions and at the same time are more likely to be financially constrained.

Furthermore, the recent collaboration between mobile money providers and commercial banks to offer credit on mobile money platforms (Suri & Jack, 2016) implies that mobile money adopters are exposed to flexible sources of finance compared to non-adopters. Thus, mobile money provides an additional lending channel to entrepreneurial firms in the developing world (Yin et al., 2019) and this can augment traditional financial services available to firms. While we recognise the credit channel as a potential mechanism, in this paper, our preferred measure of mobile money captures whether firms use mobile money for transactions or not. Therefore, we view transaction costs reduction as the main channel through which mobile money may interact with traditional financial services to influence labour productivity.

4 Data and key variables

For our analysis, we employ firm-level data from the recent World Bank Enterprise Surveys (WBES) for selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The WBES collects firm-level data on registered firms in the private sector covering both the manufacturing and the services sectors. The surveys offer a rich source of firm-level data on the business environment and firm performance indicators which are collected via face-to-face interviews with business owners and managers of small, medium and large firms. The data provide a range of information on the performance of the firms, including sales, employment as well as the cost of labour, capital and intermediate inputs. A key advantage of the WBES is that it uses a standardised sampling methodology and questionnaire. Data from the WBES are therefore internationally comparable and readily available for cross-country analyses.

Interestingly, the WBES includes a question asking whether the firms use mobile money for transactions. We take advantage of this information to address the research objective of this study. Our analysis is restricted to the 14 sub-Saharan African countries for which the mobile money question is available. These countries are Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Togo and Uganda. In total, our sample comprises around 5837 firms interviewed across these 14 countriesFootnote 5 covering the period 2013 to 2018.

4.1 Dependent variable

Our main dependent variable of interest is labour productivity. Following Aterido and Hallward-Driemeier (2011) and Kouamé and Tapsoba (2019) among others, we measure labour productivity as value added per permanent worker. The value added per worker is computed as total sales minus the total costs of inputs divided by the total number of permanent workers at the end of time t, where t is the fiscal year prior to the survey year. The total cost of inputs includes the costs of labour, materials, energy, water, transportation and communication. The sales and cost values are deflated and converted into the 2015 US dollars. To assess the robustness of our baseline findings, we also consider value added per full-time worker and sales per full-time worker, where the total number of full-time workers is adjusted for temporary workers and measured on the year of the survey. Motta (2020) notes that labour productivity measure is mostly preferred to total factor productivity (TFP) because the latter is computed as residual and hence more prone to measurement error. However, we acknowledge that TFP has its own advantages and is also a comprehensive measure of productivity.

4.2 Independent variables

Our main independent variables of interest are mobile money use and access to traditional finance variables. We measure mobile money with a dummy variable that equals 1 for firms that use mobile money for transactions at time t when labour productivity is measured and 0 otherwise. A firm is considered to use mobile money if it employs mobile money for any financial transactions such as to pay salaries of employees, to pay suppliers, to pay utility bills and to receive payment from customers, among others. Also, we use firm-level information on formal banking services to compute two different measures of access to traditional financial services that have been used by previous studies (e.g., Adegboye & Iweriebor, 2018; Aterido & Hallward-Driemeier, 2011; Chauvet & Jacolin, 2017; Lee et al., 2020). The first traditional finance variable is a dummy variable that indicates if a firm has a checking or savings account. Second, we measure access to traditional financial services with a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm has a part or all of its working capital financed with bank credit and 0 otherwise.Footnote 6 Furthermore, we measure access to capital with a continuous variable that reflects the percentage of the working capital financed with bank credit.

We include in our analysis several firm-level objective characteristics that have been considered in previous studies to affect firm productivity (Aterido & Hallward-Driemeier, 2011; Kneller & Misch, 2014; Motta, 2020). Thus, we control for firm size, the gender and experience of the manager, location of the firm, foreign ownership, ownership status, power outage, crime, export status, international certification and age of the company, among others. We also control for one-year lag of sales per worker because we anticipate that previous performance may affect both the outcome variable and the likelihood of firms to use mobile money in addition to traditional financial services (Mahlberg et al., 2013; Mahy et al., 2019),Footnote 7 among others. We account for different fixed effects to reduce omitted variable bias.

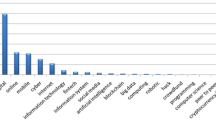

Table 1 shows that roughly 35% of the firms interviewed use mobile money for transactions. It is worth noting that there is some heterogeneity across countries. Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania record the highest use of mobile money for transactions with a total share of 61%, 44% and 39%, respectively. In contrast, Ghana and Guinea record very low mobile money users in our sample, with less than 5% of the firms using this financial innovation.

The summary statistics and the definition of variables are presented in Table 12 and 13 of the Appendix, respectively. As shown in Table 12 of the Appendix, about 87% of firms have checking or savings accounts while about 27% of firms finance part or all their working capital with bank credit. To get a general view about the use of mobile money vis-à-vis traditional financial services among firms, we tabulate firms with access to traditional finance against mobile money adopters and non-adopters as presented in Table 2. The descriptive statistics show that among firms that own checking or savings account, 64% of them do not use mobile money for transactions while 36% use mobile money for transactions. Also, 40% of firms with access to bank capital use mobile money. The evidence of the use of both mobile money and traditional finance at the firm level presents an interesting opportunity to investigate the interaction of these financial services and the implications for firm-level outcomes.

5 Empirical strategy

In this paper, we are interested in exploring the effects of mobile money and access to traditional finance on labour productivity. Let us define by \({Y}_{isc}\) our labour productivity indicator (e.g., value added per permanent worker) of firm i operating in sector s from country c. To test for whether mobile money use accentuates the effect of traditional financial services, we allow for interaction between the mobile money variable and formal finance measures and estimate the following model:

where the dummy variable MM indicates whether a firm used mobile money to make transactions. Finance is a vector of dummy variables that measure access to traditional banking services, including access to capital financed by banks and owning a checking/savings account in a bank. X is a vector of firm-level characteristics that are identified in the literature as key determinants of firm performance (see Section 4 above). s and c capture respectively the sector (i.e., ISIC 2 digit) and country fixed effects. \({\varepsilon }_{isc}\) is the error term. The standard errors are clustered at the strata level capturing country, province, location size and the sector in which firms operate.Footnote 8

The parameter on mobile money, \({\beta }_{1}\), measures the effect of mobile money use on labour productivity when the access to finance equals 0. The parameter on the variable finance, \({\beta }_{2}\), measures the effect of access to traditional financial services on firm labour productivity for firms that do not use mobile money for transactions. The parameter \({\beta }_{3}\) measures the interaction between mobile money use and access to finance. The effect of mobile money use on firm performance for firms that have access to traditional financial services is \({\beta }_{1}+{\beta }_{3}\) while the total effect of access to traditional financial services on labour productivity for firms that use mobile money for transactions is given as \({\beta }_{2}+{\beta }_{3}\).

6 Results

6.1 Labour productivity, mobile money adoption and access to traditional finance: baseline results

Table 3 presents our baseline estimation results using value added per permanent worker (in logs) as the dependent variable. First, in column (1), we regress our performance indicator on the mobile money variable (MM) and the traditional finance variables, controlling for the firm-level characteristics and the sector and country fixed effects, to ascertain if they statistically explain differences in labour productivity among firms. Second, in the last two columns, we interact the mobile money variable with the traditional finance variables to ascertain whether the former accentuates the effects of the latter on labour productivity.

As evident across column (1), the estimated coefficient on mobile money is not statistically significant. Turning to the estimates on access to traditional finance variables as presented in column (1), we find that firms that have working capital funded by banks record higher labour productivity than firms without access to such capital. Similarly, access to checking/savings account increases labour productivity. These findings are consistent with the extant literature on financial development and firm-level outcomes (e.g., Aghion et al., 2007; Beck & Demirguc-kunt, 2006; Chauvet & Jacolin, 2017; Fafchamps & Schündeln, 2013; King & Levine, 1993; Levine et al., 2000).

For the interaction between mobile money use and access to traditional finance variables reported in columns (2) and (3), we find that the interaction between access to bank capital and mobile money is positive and statistically significant at the 5% significance level while the estimate on mobile money remains insignificant and the estimate on access to capital turns insignificant. These results highlight that firms that have capital funded by banks and at the same time use mobile money for transactions have higher labour productivity compared to firms that have capital funded by banks but do not use mobile money or firms without access to capital from banks but use mobile money for transactions. Furthermore, as shown in column (3), the estimated coefficient on the interaction term between mobile money and checking/savings account is also positive although not statistically significant at the conventional levels.

In Table 4, we report for each type of financial service the marginal effect of mobile money use on labour productivity. As discussed earlier, for firms with access to finance, the marginal effect of mobile money use on labour productivity is the sum of the estimate on mobile money and the estimate on the interaction between mobile money and finance. For instance, if we consider column (2) of Table 3, the total marginal effect of mobile money for firms that do not have access to capital is equal to \({\beta }_{1}=\) 0.009 with a standard error of 0.055. The marginal effect of mobile money on labour productivity for firms that have capital funded by banks is given by \({\beta }_{1}+{\beta }_{3}\) = 0.009 + 0.203 = 0.212. This value is 0.10 when we replace bank capital by checking/savings account. To compute the standard error of the marginal effects, we take the square root of the estimated variance of \({\beta }_{1}+{\beta }_{3}\) given by the following:

Var(\({\beta }_{1}+{\beta }_{3}\)) = Var(\({\beta }_{1})\) + Var(\({\beta }_{3}\)) + 2Cov(\({\beta }_{1},{\beta }_{3}\)). As we can see in Table 4, mobile money use has positive and significant marginal effects on labour productivity for firms with access to capital and checking/savings accounts but no effect for firms that do not have access to these financial services.

Overall, our baseline results suggest that mobile money accentuates the effect of traditional financial services on labour productivity. However, the productivity gained by combining traditional financial services with mobile money is greater when traditional finance is proxied by bank capital. The findings suggest that mobile money can enable formal firms to conduct financial transactions at low costs leading to better allocation of existing financial resources (Suri, 2017). This is also consistent with previous studies which have demonstrated that mobile money can lead to a significant reduction in the costs of transactions (Jack & Suri, 2014; Jack et al., 2013) and consequently lead to significant improvement in firm-level outcomes (Islam et al., 2018).

The additional control variables added to the analysis yield interesting results. As expected, we find that exporting, firm age and having internationally recognised quality certification increase labour productivity. Similarly, firms that own or share a generator and SMEs record higher productivity than other firms. In contrast, experiencing a power outage decreases labour productivity. Among others, we do not find supportive evidence that the gender of the manager and foreign ownership of a firm significantly explain productivity differences.

We further replicate the estimations in Table 5, replacing our main dependent variable with value added per full-time worker and sales per full-time worker in logs, adjusting for short term workers, to check for the robustness of our findings. The results corroborate the previous ones reported in Table 3. In fact, we do not find any significant direct effect of mobile money use on labour productivity per worker. However, when we interact mobile money with bank capital and checking/savings account, productivity improves.

In Table 6, we provide additional evidence on the interaction between access to capital and mobile money use where access to capital is measured as the ratio of working capital that is funded by formal banks. In our data, this value varies from 0 for firms that do not have any capital funded by banks to 1 for firms that have all their capital funded by formal banks. One may argue that firms that access capital from banks may use such financial resources to invest in assets and use other financial resources for their day-to-day operations. In such a scenario, looking at the interaction between mobile money and capital is more relevant for firms that use their capital in operational transactions. Therefore, we also test if our findings differ between firms that invested in assets during the last fiscal year and firms that did not invest. For firms that invested, we compute the average of the percentage of working capital funded by banks and the percentage of assets funded by banks.

The results in the first column of Table 6 are obtained using the full sample of both firms that invested in assets and firms that did not invest. In line with our previous results, we find that an increase in the ratio of capital funded by formal banks has higher labour productivity when mobile money is used for transactions. In column (2), we restrict our sample to firms that did not invest in assets in the last fiscal year assuming that their capital is used for their production costs. As evident in Table 6, the interaction between access to capital and mobile money for this category of firms is positive and statistically significant. In the last column, we restrict our sample to firms that invested in the last fiscal year and, for these firms, we compute the average of the capital and investments funded by formal banks. The results show no significant effect on the interaction between bank capital and mobile money use.

6.2 Small versus large firms

It is well documented in the literature that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have less access to formal finance than larger firms (Beck & Demirguc-kunt, 2006; Beck et al., 2005). Also, previous studies have found that small firms benefit more from mobile money adoption compared to large firms (Islam et al., 2018). As earlier intimated, mobile money transactions are cost-effective for small transfers (McKay & Pickens, 2010). Given that SMEs are more likely to conduct low-value transactions, we examine whether the use of mobile money in addition to traditional finance is more beneficial to these firms. We split our sample into SMEs and large firms. To define the size of the firm we employ the same cutoff used in the World Bank Enterprise Surveys where a firm that employs less than 100 people is considered an SME while a firm with at least 100 employees is a large firm. We use the number of permanent employees in the last previous year that coincides with the year labour productivity is measured in our analysis to classify firms into SMEs and large firms.

Table 7 shows the estimation results using value added per permanent worker as the dependent variable. The results for the sample of SMEs are shown in columns (1)–(3). Similar to the baseline results reported in Table 3, the interaction between mobile money and bank capital affects labour productivity positively, indicating that SMEs that have working capital funded by banks and at the same time use mobile money have higher labour productivity than other SMEs. For the sample of large firms (see columns (4)–(6)), the interaction term between access to bank capital and mobile money is not statistically significant but positive and significant when we proxy access to traditional finance by Checking/Saving account. Table 8 (columns (1) and (2)) presents the marginal effect of mobile money use by access to finance for the SMEs and large firm samples. The results show that for SMEs, mobile money use has a positive and significant marginal effect on labour productivity for firms with bank capital on the one hand and those with checking/savings accounts on the other. However, the marginal effect of mobile money on labour productivity is not statistically significant for firms with no access to these traditional financial services. For the sample of large firms, we do not find a significant effect of mobile money use on labour productivity regardless of the measure of access to traditional finance that we consider. It is worth indicating that there a significant drop in observations for the large firm sub-sample compared to the SMEs sample. Therefore, we compare the results of the two sub-samples with caution.

6.3 Sensitivity analysis

In this section, we run several robustness checks. First, we split the sample between East African countries that have higher mobile money adoption and the other countries with lower mobile money adoption to check whether the results will differ between high adopters and low adopters. Second, we include region fixed effects and change the deflating baseline year. Finally, we test if our results hold when we exclude the lagged performance measure (sales per worker) as a control variable in the baseline model and when we replace the sales per worker with the lag value of sales and with lag sales per worker quartile dummies.

6.3.1 East African countries (leaders in mobile money adoption) versus other countries

The penetration of mobile money payment and its expansion has not been at the same pace across African regions. Leaders in mobile money use are mostly from East African regions, and since the launch of M-PESA in 2007, Kenya has emerged as the global leader in mobile money adoption and deployment (Suri & Jack, 2016). As we illustrated in Table 1 in the descriptive statistics section, Kenya has the highest percentage of firms using mobile money followed by Uganda and Tanzania. Because of the differences between the East African region and other regions in Africa, we divide our sample between East African countries and other countries in the sample and re-run our regressions to check if our results are driven by these leaders in mobile money use.

The results are reported in Table 9 For each group of countries, we estimate the baseline model for the full sample and then for the SMEs. The results for the sample of East Africa are reported in columns (1)–(6), whereas the estimates for other countries are shown in columns (7)–(12). For the three East African countries, the estimations for the full sample are reported in columns (1)–(3). The evidence in column (1) shows that mobile money use has a positive and statistically significant effect on labour productivity so is access to bank capital. The interaction term between mobile money and bank capital is also significant. We find similar evidence for the sample of SMEs as reported in columns (4) to (6).

Turning to the sample of the other countries with lower mobile money adoption, we do not find any significant direct effect of mobile money use on labour productivity. However, the interaction term on the variable mobile money and bank capital on one hand (column 8) and checking/saving accounts on the other (column 9) are positive and statistically significant. In column (9) where mobile money interacts with checking/saving account, we find a negative effect of mobile money, but the total effect is positive albeit not statistically significant. The results for the SMEs reported in columns (10) to (12) are similar to those obtained with the full sample. These results suggest that combining mobile money with traditional financial services can lead to some positive effects on labour productivity. Table 8 (columns (3)–(6)) shows that across the different sub-samples, the total marginal effect of mobile money use on labour productivity is positive for firms that access traditional financial services with a higher and more significant effect for access to bank capital.

6.3.2 Accounting for region fixed effects and deflating with the year 2010

Let us note that the country fixed effects are absorbed by the region fixed effects when both are controlled for in the estimations. Therefore, we interact the country fixed effects with the sector fixed effects, allowing the country-specific effects to vary across sectors within a country. This would mean, for instance, that the effects of any policies implemented in a country on labour productivity depend on the sector where firms operate. As we can see, the results reported in Table 10 remain robust. The interaction terms between mobile money and the traditional finance variables remain positive and statistically significant. Additionally, we find a robust estimate for the interaction between mobile money and access to bank capital for the sample of SMEs as indicated in column (5).Footnote 9

In the previous analysis, the sales data are converted into the 2015 US dollar. We re-estimate our equations converting the sales data into 2010 US dollars to check if our results are sensitive to the base year used. The findings are shown in Table 11. The results for both the full sample and the SMEs sample suggest that combining mobile money and traditional financial services (bank capital) is beneficial for firm productivity improvement, confirming our baseline results reported in Table 3 and Table 7.

6.3.3 Excluding the lagged sales per worker variable as a control in the baseline model

As earlier indicated, we include one year lag of sales per worker in our model as an additional control for two main reasons. First, we add this variable because current labour productivity is likely to be influenced by previous performance. Second, performance in the past may affect firms’ decision to use mobile money in addition to traditional financial services. Ignoring this variable will lead to an omission of an important factor that affects both the outcome variable and the independent variables of interest. However, the inclusion of a lagged dependent variable as control may introduce another econometric problem. Adding the lagged dependent variable may correlate with the error term giving rise to endogeneity that could be addressed by using GMM methods. Because the dataset employed for our study is cross-sectional but not panel, we cannot use GMM as other studies have done to test the robustness of the OLS estimations (e.g., Mahlberg et al., 2013; Mahy et al., 2019). In our case, instead of directly adding the lagged dependent variable because of lack of information about lag of inputs cost, we control for one-year lag of sales per worker as a proxy for past performance.

Nonetheless, we test for the sensitivity of the results by estimating our baseline model without the lagged sales per worker variable. The results of the full sample as reported in Table 15 in the Appendix show that mobile money has no significant effect on productivity while traditional financial services have positive and significant direct effects on labour productivity. This result confirms our baseline estimates in Table 3. Further, the interaction term between mobile money and bank capital on one hand and checking/saving account on the other loses significance. However, the interaction between mobile money and the traditional finance variables is significant for low mobile money adopting countries. The interaction between mobile money and checking/saving account is also significant among the sub-sample of large firms albeit at 10% significance level.

For additional robustness checks we replace the one-year lag of sales per worker with one year lag of sales, and then by quartile dummies computed using the year lag of sales per worker to capture the different past performance groups. The results which are reported in Table 16 and Table 17 of the Appendix suggest that the use of mobile money and traditional financial services can lead to productivity improvement.

7 Conclusion

This paper investigates the effects of mobile money and access to traditional financial services on firm labour productivity and explores whether the interaction between the former and the latter is beneficial to productivity using firm-level data for 14 sub-Saharan African countries. We find that mobile money has no robust significant effect on labour productivity. However, when mobile money is combined with bank capital and to some extent bank accounts, then there is evidence of productivity improvement. This also tends to be the case for the subsample of small and medium-sized enterprises. The productivity gain from combining mobile money use with traditional financial service is also found within firms from East Africa and firms from other regions where mobile money is emerging, but uptake is relatively low. The complementarity effect between mobile money and traditional financial services is potentially due to the extra benefit that firms may derive from mobile money use such as a reduction in transaction costs and thereby enabling firms to use available financial resources efficiently. While we do not find a direct effect of mobile money use among SMEs, future studies may explore this possibility among microenterprises where small value transactions are more prevalent. Most importantly, future studies may explore the interplay between mobile money and traditional financial services and how these interactions affect other performance indicators such as growth which we have not covered in this study due to data constraints and high endogeneity concerns.

Overall, our finding has interesting implications for policy particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where mobile money services are pervasive and significant investment has been made towards the promotion of mobile money adoption. While mobile money services have become indispensable in financial transactions due to weak banking infrastructure in most African countries, our evidence suggests that it is important for financial inclusion policies to promote access to both mobile money and existing financial services among formal firms. This will enable entrepreneurs to take advantage of the strengths that are inherent in mobile money on one hand and traditional financial services on the other to improve firm performance.

We acknowledge that our study is not immune to some methodological limitations due to the cross-sectional nature of our study. Most importantly, it is always useful to employ instrumental variable techniques to address possible endogeneity concerns that are common in cross-sectional studies. However, while we employ several robustness checks to confirm our results, we are not able to employ instrumental variable techniques as additional robustness checks due to data limitation. For example, distance to mobile money agents is popularly used in the literature as an instrument for mobile money adoption. However, in our case, the use of this instrument is not feasible given that mobile money agent location data is not available for most African countries. Therefore, our estimates should not be interpreted as causal. We however consider our study as a starting point for further studies which may focus on the implications of the coexistence between traditional finance and financial innovation for private sector development in sub-Saharan Africa.

Notes

See Bencivenga, Smith and Starr (1995) and Greenwood and Jovanovic (1990) for theoritical evidence.

In most African countries, mobile money transactions and account ownership continue to grow exponentially, and in some countries, there are more mobile money accounts than bank accounts (GSMA, 2017). In Kenya, for instance, mobile money is used by at least one individual in 96% of households which makes the country the world leader in mobile money adoption (Suri & Jack, 2016).

Gosavi (2015) finds that firms that use traditional financial services are more likely to employ mobile money for transactions.

McKay and Pickens (2010) define branchless banking “as the delivery of financial services outside conventional bank branches using information and communications technologies and nonbank retail agents.”.

We do not include Zambia in the analysis as it has a few mobile money users (less than 3%), and there are some possible outliers found in the measure of labour productivity.

Previous studies have also considered line of credit or loan from financial banks, but in this paper, we hardly find significant effects on the interaction between mobile money use and the line of credit or loan variable. Thus, we decide to focus on bank capital and account ownership.

Mahy et al. (2019) and Mahlberg et al. (2013) controlled for 1-year lag of value added per worker, and in addition to the OLS and FE estimations, they also provided generalised method of moments (GMM) models to check the robustness of their results. But because of lack of data on cost of inputs at t − 1, we cannot control for the 1-year lag of our main dependent variable (value added per worker). Instead, we control for the lag of sales per worker. Furthermore, because our data are not panel, we cannot estimate GMM models. Avenyo et al. (2019), in their cross-sectional analysis on the impact of product innovation on employment, control for 1-year lag of employment.

Although the data have different levels, we decided not to employ a multilevel model because it has been shown in the literature that results from multilevel models should be interpreted with caution when the number of observations at the higher level (country in our case) is lower than 30 (Browne & Draper, 2000; Maas & Hox, 2005) or 20 (Lai & Kwok, 2015) because the standard errors of the estimations on the variables at the highest level are likely to be biased.

Results for the sample of large firms are not significant, but to save space, we did not report them.

References

Abdmoulah, W., & Jelili, R. B. (2013). Access to finance thresholds and the finance-growth nexus. Economic Papers, 32(4), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-3441.12059

Adegboye, A. C., & Iweriebor, S. (2018). Does access to finance enhance SME innovation and productivity in Nigeria? Evidence from the world bank enterprise survey. African Development Review, 30(4), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12351

Aghion, P., Fally, T., & Scarpetta, S. (2007). Credit constraints as a barrier to the entry and post-entry growth of firms. Economic Policy, 22(52), 731–779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2007.00190.x

Allen, F., Carletti, E., Cull, R., Qian, J. Q. J., Senbet, L., & Valenzuela, P. (2014). The African financial development and financial inclusion gaps. Journal of African Economies, 23(5), 614–642. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/eju015

Allen, F., Carlett, E., Cull, R., Qian, J., Senbet, L., & Valenzuela, P. (2012). Resolving the African financial development gap: Cross-country comparisons and a within-country study of Kenya. NBER Working Paper No.18013. Cambridge.

Arabehety, P. G., Chen, G., Cook, W., & McKay, C. (2016). Digital finance interoperability & financial inclusion: A 20-country scan. Washington, D.C.: CGAP. Retrieved from: https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/researches/documents/interoperability.pdf. Accessed 12 March 2022.

Asamoah, D., Takieddine, S., & Amedofu, M. (2020). Examining the effect of mobile money transfer (MMT) capabilities on business growth and development impact. Information Technology for Development, 26(1), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2019.1599798

Aterido, R., & Hallward-Driemeier, M. (2011). Whose business is it anyway? Closing the gender gap in entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa. Small Business Economics, 37(4), 443–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9375-y

Avenyo, E. K., Konte, M., & Mohnen, P. (2019). The employment impact of product innovations in sub-Saharan Africa: Firm-level evidence. Research Policy, 48(9), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103806

Baumol, W. J. (1952). The transactions demand for cash: An inventory theoretic approach. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 66(4), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.2307/1882104

Beck, T., & Demirguc-kunt, A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(11), 2931–2943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.009

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2005). Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter? The Journal of Finance, 60(1), 137–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00727.x

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Honohan, P. (2009). Access to financial services: Measurement, impact, and policies. The World Bank Research Observer, 24(1), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkn008

Beck, T., Pamuk, H., Ramrattan, R., & Uras, B. R. (2018). Payment instruments, finance and development. Journal of Development Economics, 133, 162–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.01.005

Blumenstock, J. E., Callen, M., Ghani, T., & Koepke, L. (2015). Promises and pitfalls of mobile money in Afghanistan: Evidence from a randomized control trial. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (p. 15). ACM. Blumenstock,; J., & Eagle, N. https://doi.org/10.1145/2737856.2738031

Boermans, M. A., & Willebrands, D. (2018). Financial constraints matter: Empirical evidence on borrowing behavior, microfinance and firm productivity. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 23(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946718500085

Bokpin, G. A., Ackah, C., & Kunawotor, M. E. (2018). Financial access and firm productivity in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Business, 19(2), 210–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2018.1392837

Chauvet, L., & Jacolin, L. (2017). Financial inclusion, bank concentration, and firm performance. World Development, 97, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.018

Dalton, P. S., Pamuk, H., Ramrattan, R., Soest, D. van, & Uras, B. (2019). Transparency and financial inclusion: Experimental evidence from mobile money. CentER Discussion Paper No. 2018-042. Tilburg. Retrieved from: https://pure.uvt.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/31433015/2019_032.pdf. Accessed 12 March 2022.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). The Global Findex Database 2014: Measuring financial inclusion around the world. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7255. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-7255

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Jake, S. A., & Hess, J. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1259-0.

Donovan, K. P. (2015). Mobile Money. In R. Mansell & P. H. Ang (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of digital communication and society (pp. 1-7). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118767771.wbiedcs023

Fafchamps, M., & Schündeln, M. (2013). Local financial development and firm performance: Evidence from Morocco. Journal of Development Economics, 103(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.01.010

Ghunaim, N. (2020). Enabling financial inclusion in developing economies. Journal of Payments Strategy and Systems, 14(2), 186–194.

Girma, S., & Vencappa, D. (2015). Financing sources and firm level productivity growth: Evidence from Indian manufacturing. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 44(3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-014-0418-7

Gosavi, A. (2015). The next frontier of mobile money adoption. International Trade Journal, 29(5), 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853908.2015.1081113

Gosavi, A. (2018). Can mobile money help firms mitigate the problem of access to finance in Eastern sub-Saharan Africa? Journal of African Business, 19(3), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2017.1396791

Greenwood, J., & Jovanovic, B. (1990). Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. The Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 1076–1107.

Grüschow, R. M., Kemper, J., & Brettel, M. (2016). How do different payment methods deliver cost and credit efficiency in electronic commerce? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 18, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2016.06.001

GSMA. (2015). 2015 State of the industry report: Mobile money. Retrieved from: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/SOTIR_2015.pdf. Accessed 12 March 2022.

GSMA. (2017). State of the industry report on mobile money. Retrieved from http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/GSMA_State-of-the-Industry-Report-on-Mobile-Money_2016.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2018.

Islam, A., Muzi, S., & Meza, R. J. L. (2018). Does mobile money use increase firms’ investment? Evidence from Enterprise Surveys in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. Small Business Economics, 51(3), 687–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9951-x

Islam, A., & Muzi, S. (2020). Mobile money and investment by women businesses in sub-Saharan Africa. Policy Research Working Paper No. WPS 9338. World Bank.

Jack, W., & Suri, T. (2014). Risk sharing and transactions costs: Evidence from Kenya’s mobile money revolution. American Economic Review, 104(1), 183–223. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.1.183

Jack, W., Ray, A., & Suri, T. (2013). Transaction networks: Evidence from mobile money in Kenya. American Economic Review, 103(3), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.356

Kahn, C. M., & Roberds, W. (2009). Why pay? An introduction to payments economics. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 18(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2008.09.001

King, R. G., & Levine, R. (1993). Finance, entrepreneurship, and growth: Theory and evidence. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32, 513–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(93)90028-E

Kneller, R., & Misch, F. (2014). The effects of public spending composition on firm productivity. Economic Inquiry, 52(4), 1525–1542. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12092

Kouamé, W. A., & Tapsoba, S. J. A. (2019). Structural reforms and firms’ productivity: Evidence from developing countries. World Development, 113, 157–171.

Lee, C.-C., Wang, C.-W., & Ho, S.-J. (2020). Financial inclusion, financial innovation, and firms’ sales growth. International Review of Economics & Finance, 66, 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2019.11.021

Levine, R., Loayza, N., & Beck, T. (2000). Financial intermediation and growth: Causality and causes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 46, 31–77.

Mahlberg, B., Freund, I., Cuaresma, J., & Prskawets, A. (2013). Ageing, productivity and wages in Austria. Labour Economics, 22, 5–15.

Mahy, B., Rycx, F., Vermeylen, G., & Volral, M. (2019). Productivity, wages and profits: Does firms’ position in the value chain matter? IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 12795. IZA – Institute of Labour Economics.

Maurer, B. (2012). Mobile money: Communication, consumption and change in the payments space. Journal of Development Studies, 48(5), 589–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2011.621944

Mbiti, I., & Weil, D. N. (2016). Mobile banking: The impact of M-Pesa in Kenya. In S. Edwards, S. Johnson, & D. N. Weil (Eds.), African successes, volume III: Modernization and development (pp. 247–293). University of Chicago Press.

McKay, C., & Pickens, M. (2010). Branchless banking 2010: Who’s served? At what price? What’s next? CGAP Focus Note No. 66. Retrieved from: https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/researches/documents/CGAP-Focus-Note-Branchless-Banking-2010-Who-Is-Served-At-What-Price-What-Is-Next-Sep-2010.pdf. Accessed 12 March 2022.

Motta, V. (2020). Lack of access to external finance and SME labor productivity: Does project quality matter? Small Business Economics, 54(1), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0082-9

Pelletier, A., Khavul, S., & Estrin, S. (2020). Innovations in emerging markets: The case of mobile money. Industrial and Corporate Change, 29(2), 395–421. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtz049

Sleuwaegen, L., & Goedhuys, M. (2002). Growth of firms in developing countries, evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Development Economics, 68(1), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(02)00008-1

Suri, T. (2017). Mobile Money: Annual Review of Economics, 9, 497–520. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-063016-103638

Suri, T., & Jack, W. (2016). The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science, 354(6317), 1288–1292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah5309

Sy, A. N. R., Maino, R., Massara, A., Perez-Saiz, H., & Sharma, P. (2019). FinTech in sub-Saharan African countries: A game changer? African Departmental Paper No. 19/04, International Monetary Fund. Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2019/02/13/FinTech-in-Sub-Saharan-African-Countries-A-Game-Changer-46376. Accessed 12 March 2022.

Talom, F. S. G., & Tengeh, R. K. (2020). The impact of mobile money on the financial performance of the SMEs in Douala, Cameroon. Sustainability, 12(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010183

White, K. J. (1975). Consumer choice and use of bank credit cards: A model and cross-section results. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1086/208611

Whitesell, W. C. (1989). The demand for currency versus debitable accounts. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 21(2), 246–251. https://doi.org/10.2307/1992373

Whitesell, W. C. (1992). Deposit banks and the market for payment media. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 24(4), 483–498. https://doi.org/10.2307/1992806

Yin, Z., Gong, X., Guo, P., & Wu, T. (2019). What drives entrepreneurship in digital economy? Evidence from China. Economic Modelling, 82, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.09.026

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers and Associate Editor for their constructive comments and suggestions. Our thanks also go to Romain Fourmy, Pierre Mohnen, Micheline Goedhuys and the participants at the UNU-MERIT 2020 internal conference for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Tables

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17 and

18.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Konte, M., Tetteh, G.K. Mobile money, traditional financial services and firm productivity in Africa. Small Bus Econ 60, 745–769 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00613-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00613-w