Abstract

This article aims to capture the relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm size. This aim is pursued by developing a novel data-driven identification strategy that assigns firm size groups based on their statistical relationships to perceived growth barriers. The analysis is undertaken using data for approximately 44,000 Swedish SMEs (0–249 employees) for 2011, 2014, and 2017. The results suggest that small firms typically face constraints on equity financing, whereas larger firms face barriers regarding competition and recruitment. As a benchmark, the performance of the developed method is compared with prevailing strategies that use ad hoc firm size groups. The findings show that ad hoc groups fail to accurately capture size thresholds at which firms incur barriers, and they yield a consistently lower model fit compared with the method proposed here. Consequently, there may be a need for methodological rethink in the field regarding the treatment of firm size.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, research on small business has moved from receiving sparse attention to becoming a recognized academic field. This research has had a large impact on the political debate, in which policymakers are showing increased interest in the entry and growth of young and small firms (Gilbert et al. 2004; Henrekson and Stenkula 2010; McCann and Ortega Argiles 2016). However, there are concerns that their growth is constrained by internal and external barriers. Furthermore, there is currently little knowledge regarding which firms face growth barriers and, moreover, in what respect. In other words, although policymakers are willing to stimulate firm growth, there is currently a general uncertainty as to which factors to address and how.

Meanwhile, economic theory suggests that growth barriers are intimately associated with firm size, where the nature of these barriers is likely to change as firms grow. Prominently, firm growth is thought to be inhibited by constraints on management, liquidity, and financing as well as access to skilled labor (e.g., Penrose 1959; Storey 1994; Audretsch and Elston 2002; Nyström and Elvung 2014; Palazuelos et al. 2018). Moreover, these issues risk being exacerbated by institutional constraints (e.g., Henrekson and Johansson 1999; Bornhäll et al. 2017). Despite these conceptualizations, however, there is limited empirical evidence on the relationship between growth barriers and firm size.

Prior empirical work has typically used perceived growth barriers to identify factors that constrain business growth, where these perceptions are typically those of owners and/or top managers of firms (e.g., Levy 1993; Okpara and Wynn 2007; Lee 2014; Lee and Luca 2019). A common conclusion derived from this literature is that firms with 5–50 or, alternatively, 10–49 employees are more likely than other firms to face growth barriers, where firms have been studied using standardized, so-called “ad hoc,” definitions of firm size (e.g., Orser et al. 2000; Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006; Lee and Cowling 2014, 2015).Footnote 1

The previous literature on perceived growth barriers is, however, limited in two respects. First, whereas previous analyses have used ad hoc firm size groups, the applicability of these groups to capture firm growth barriers has not been evaluated. Hence, in the absence of a benchmark, the literature is currently lacking an empirical backdrop against which its results can be interpreted. Moreover, and as a consequence of this constraint, there is also currently limited information with which to guide the design of future research. Second, as previous analyses have assigned firms into ad hoc assigned size groups, they are unlikely to have captured the specific size thresholds at which firms incur growth barriers, which limits our understanding of the concept. Given the above limitations, as well as the considerable academic and political interest in firm growth barriers, it is imperative that the matter be investigated further.

The aim of this article is threefold. The first aim is to capture the relationship between firm size and perceived growth barriers. This aim is pursued by developing a regression-based identification strategy that uses model predictive power (adjusted R2) and Kernel density weights to assign firm size groups. The second aim is to apply this method to an extensive cross-sectional dataset that covers approximately 44,000 Swedish micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs, 0–249 employees) for the years 2011, 2014, and 2017. The third aim is to evaluate the performance of ad hoc firm size groups in explaining perceived growth barriers. This aim is achieved by comparing predictions and goodness-of-fit statistics across strategies.

This article contributes to the literature in at least three ways. First, it presents a novel data-driven methodology to study perceived growth barriers that offers greater precision and flexibility than previous methods. Specifically, previous methods have generally involved strong assumptions on the nature and confines of economic phenomena across firm size, whereas the proposed methodology overcomes these issues by instead allowing data to shape the analysis. In this way, the present article connects to an emerging interest in using data-driven methods to study firm growth (e.g., Miyakawa et al. 2017; Coad and Srhoj 2019). Second, it presents the first analysis to evaluate the performance of ad hoc firm size groups with respect to perceived growth barriers, thereby providing a fundamental empirical benchmark for research in an expanding field. Third, the generalizability of the developed method allows it to be applied across a diverse range of empirical settings. Through this contribution, the article presents a solution to a common methodological issue within entrepreneurship research, i.e., how to assign discrete firm size groups.

By applying the developed identification strategy, it is found that firms with 76–144 employees are more likely than those with 0–14 employees to face barriers due to competition. Next, firms with 0–19 employees are found to be more likely than those with 41–249 employees to face growth barriers related to access to equity financing. However, they are less likely than those with 41–249 employees to face growth barriers related to recruiting staff. It is suggested that the similarity between these two results may reflect that financial resources are a binding constraint among smaller firms, whereas competition and recruitment may be more prominent constraints among larger ones.

A comparison of the results across strategies reveals that the developed identification strategy widely outperforms its ad hoc counterparts as it is able to account for the same mechanisms as the ad hoc methods while also allowing researchers to make detailed predictions on the size thresholds at which firms incur, versus overcome, growth barriers. In contrast, ad hoc groups are found to generally overshoot the size thresholds at which firms incur growth barriers and to instead attribute the prevalence of perceived growth barriers to generic and considerably wider ranges of firm size.Footnote 2

The above notion is further strengthened upon evaluating the model fit of the applied strategies (McFadden’s pseudo R2), whereby the proposed identification strategy yields a consistently better fit than achieved by competing discrete measures of firm size. Based on these results, it is concluded that the use of ad hoc firm size groups likely limits our understanding of firm growth barriers and their antecedents. Given this insight, there may be a need to rethink the current treatment of firm size. Specifically, there may be a need for researchers to reevaluate the role of ad hoc strategies in empirical analysis.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. The next section presents a brief summary of the previous empirical literature on perceived firm growth barriers. The “Data” section provides detail on the data used, and the “Empirical strategy” section discusses the empirical method. The “Econometric model” section contains the results of the econometric analysis. The “Dependent variables” section provides concluding remarks.

2 Previous empirical literature

The previous literature provides a number of indications of the connection between growth barriers and firm size. Prominently, the previous empirical literature suggests that the emergence of growth barriers is intimately connected to firm characteristics, such as their age, management, size, and ownership (e.g., Orser et al. 2000; Okpara 2011; Coad and Tamvada 2012; Lee 2014). Moreover, research also suggests that the nature of growth barriers is partly context dependent, and they have been noted to vary across institutional and regional settings (e.g., Henrekson and Johansson 1999; Okpara and Wynn 2007; Lee and Cowling 2015; Wang 2016; Lee and Luca 2019).

Despite a growing interest in perceived growth barriers, however, there is currently limited evidence on their relationship to firm size. This observation is noteworthy, given the central role of firm size in explaining overall firm behavior and performance (e.g., Birch 1979; Henrekson and Johansson 2010; Anyadike-Danes et al. 2015). In turn, this situation implies that a central determinant of firm performance remains largely unexplored in this literature. Although limited, there is nonetheless a handful of studies on perceived growth barriers that address this relationship. This research suggests that firms with 5–50 and 10–49 employees are generally more likely than others to face growth barriers (i.e., Beck et al. 2005; Beck and Demirguc-Kunt 2006; Oliveira and Fortunato 2006; Lee and Cowling 2014; Lee and Cowling 2015).

Most closely related to this article is that of Beck et al. (2005), who examine the relationship between firm size, firm growth and perceived growth barriers involving finance, law, and corruption. The authors use cross-sectional data on firms with 5 employees or more, covering a total of 4255 firms across 54 countries. Using these data, they study the influence of firm characteristics on perceived growth barriers and the relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm growth. The variable of interest, firm size, is measured according to the World Bank (2001) definition, i.e., by assigning firms into the categories 5–50, 50–500, and more than 500 employees. The authors find that firms with 5–50 employees are more likely than larger ones to face perceived growth barriers related to financing and corruption. They also establish a significant negative relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm growth.

Although in many cases quantitatively impressive, however, prior studies have likely been limited by the use of ad hoc definitions of firm size. As a consequence, they are unlikely to have fully captured the relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm size. Given this limitation, it is imperative that the matter be explored further.

3 Data

This article utilizes Swedish data from the business survey “The Situation and Conditions of Enterprises” (SCE; Företagens villkor och verklighet) which is conducted by the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (Tillväxtverket). The survey concerns business climate and targets top managers of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The motivation for studying a single economy, as opposed to conducting a multinational analysis, arises from the limitations in available multinational datasets but also from an effort to keep the institutional context constant across firms.Footnote 3 The choice to study Sweden, in particular, arises from the fact that the SCE constitutes by far the largest business survey of its kind, and its data are fully linkable to all Swedish administrative registers. Hence, due to its large scale and high quality, the SCE is argued to offer unparalleled opportunities to disentangle the perceived growth barrier construct.

Within the context of the data, SMEs are defined as firms with 0–249 employees with an annual turnover exceeding approximately €20,000 (200,000 Swedish Crowns), i.e., in accordance with the OECD (2005) definition of SMEs. The data are collected through a mail questionnaire that is sent to a stratified random sample of Swedish SMEs.Footnote 4 The data have been stratified based on the size, industry, and geographical location of firms, as well as the age and gender of top managers. As they have been sampled based on a number of total population statistics, the data provide a detailed representation of the aggregate population of SMEs.

This article utilizes data from the 4th, 5th, and 6th waves of the survey, which were collected in 2011, 2014, and 2017, respectively.Footnote 5 In total, approximately 93,000 firms were contacted, out of which approximately half responded, for a total of 43,511 firms. Moreover, the survey data have been combined with administrative data from Statistics Sweden on firm and top manager characteristics for the end of 2010, 2013, and 2016.

Within the content of the SCE, top managers are asked to state their views on whether a set of factors constitutes barriers to growth. They are also asked to state the intensity of each barrier on a three-point Likert scale ranging between 0 and 2. A rating of 0 corresponds to that a given factor constitutes “No barrier to growth,” 1 “A moderate barrier to growth” and 2 to “A significant barrier to growth.”Footnote 6

4 Empirical strategy

4.1 Econometric model

This article uses a probabilistic model to test the likelihood that top managers perceive a certain factor to be a barrier to growth given firm and top manager characteristics. In line with previous studies, it focuses on whether top managers face significant growth barriers (e.g., Coad and Tamvada 2012; Lee 2014; Lee and Cowling 2015). In other words, the outcome variables, perceived growth barriers, are treated as binary, where top managers either perceive a given factor to be a significant growth barrier or not.Footnote 7

Formally, a probit model is used to test the likelihood that the top manager of firm i at time t perceives factor j to be a significant growth barrier in the following model:

4.2 Dependent variables

The dependent variables of this article comprise eight binary variables, which constitute all comparable growth barriers available in the SCE over the studied period. More specifically, the analysis concerns growth barriers related to competition (Competition), access to credit (Credit), lack of demand (Demand), access to equity financing (Equity financing), current plant capacity (Plant capacity), lack of profits (Profits), recruiting staff (Recruitment), and regulations (Regulations).Footnote 8

4.3 Identifying firm size categories

The variable of interest in this article is firm size (Size). The reason for studying this particular variable, as opposed to a range of firm characteristics, is because firm size constitutes a key variable in both research and policy analysis on firm performance, whereby its academic and economic significance is argued to warrant a dedicated and in-depth analysis. Studies of perceived growth barriers have previously analyzed their relationship to firm size by use of ad hoc–defined size groups (e.g., Orser et al. 2000; Beck et al. 2005; Lee and Cowling 2014; Lee and Cowling 2015).

Although appealing in their simplicity and comparability, however, a major drawback to the use of ad hoc firm size groups is that they are unlikely to correspond to the heterogeneity of most economic problems. This incompatibility implies that by adopting these strategies, researchers are also likely to restrict their abilities to capture economic phenomena. Given these constraints, this article aims to instead capture the relationship between firm size and perceived growth barriers through a data-driven approach. This aim implies, in turn, a need for careful methodological consideration.

First, there are a number of established ways to define firm size, such as in terms of value added, sales, or the number of employees. In this article, size is defined as the total number of employees per firm. Employment is chosen over alternative definitions because it has proven to be a more consistent and stable measure across industries and time (Delmar 1997; Davidsson et al. 2006; Coad and Hölzl 2012).Footnote 9 Next, having decided on a definition of firm size, the next question is how to analyze it. In principle, there are two ways to approach this issue: (a) by treating firm size as a continuous estimator or (b) as a discrete estimator. At first glance, it may seem that the obvious way to approach this problem is to opt for (a), i.e., to treat firm size as a continuous estimator and thereby use all available information to assess its relationship to perceived growth barriers. However, due to data limitations, this is not necessarily the case. In particular, due to the structure of the data, i.e., left-skewed with relatively few observations for firms with 50 employees or more, a continuous estimator will tend to be disproportionally imprecise for these firms.Footnote 10 Meanwhile, given that this article aims to explore the general relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm size, a continuous estimator of firm size is likely to be unsuitable for this context; rather, it implies the need for a discrete measure.

In contrast to a continuous estimator, a discrete measure of firm size is appealing in that it allows for analysis of wide sets of firm sizes. Moreover, this approach also offers an intuitive way to evaluate non-linear relationships. However, a drawback of this approach is that there is little consensus on how to assign firm size groups. Furthermore, by wrongfully assigning size groups, researchers run risk of understating, overstating, or even obscuring the mechanisms studied.

To address this challenge, this article aims to identify firm size groups based on the statistical relationship between their size and perceived growth barriers. In this way, it aims to incorporate part of the advantages of a continuous estimator, i.e., flexibility and adaptability, while also incorporating part of the advantages of a discrete estimator, i.e., inclusiveness. To approach this task, a set of firm and top manager characteristics are included in a number of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models along with a set of dummy variables that assume the value of “1” for each consecutive firm size interval between 0 and 249 employees.Footnote 11 Each firm size interval is included individually for each growth barrier in a number of regressions, as follows:

where Ω denotes a set of firm and top management characteristics, in excess of firm size, and j denotes each category of perceived growth barriers. In addition, Z denotes each individual firm size group. For brevity, time and individual indices are suppressed.

Next, once each growth barrier has been regressed against all firm sizes, the model fit of each size group is evaluated in terms of adjusted R2. All regression models are thereafter ranked based on their adjusted R2 value, where the firm size group that yields the highest predictive power is included in the model. Thereafter, the process is repeated to identify the second interval for each barrier following the same principle, where the first firm size group is now included in each regression. This process is repeated for all growth barriers until all firm sizes have been categorized from 0 to 249 employees.

The adjusted R2 measure is, however, sensitive to variance. For the context of this article, this sensitivity poses a problem. As previously discussed, the data contain relatively few observations for firms with 50 employees or more, which means that estimates for this group exhibit relatively high variance. Therefore, if firm size intervals were to be assigned based on adjusted R2 alone, the resulting groups would tend to focus on firms in this category while obscuring relationships among smaller firms. Therefore, to yield more inclusive estimates, the predictive value of each firm size group is weighted by its estimated Kernel density (Epanechnikov).Footnote 12 Analysis shows that this approach does not affect the identification of groups among firms with 50 employees or more but rather allows the algorithm to also identify such groups among smaller ones.

Moreover, to reduce the number of possible categories, the Kernel estimator is also used to identify Kernel bandwidths. This property is utilized to restrict the model in that it cannot fit two complete firm size groups within the same Kernel bandwidth. By use of this restriction, the risk of introducing small, affluent groups is reduced. This approach yields an initial total of 50 firm size groups per growth barrier.

Finally, to increase econometric efficiency and to make the results more readable, the above process is repeated for the initial 50 groups in an effort to increase group sizes (the number of observations per group), where Kernel density weights are now assigned to each group rather than to each individual firm size. By this, the possibility of merging groups is explored, where the influence of individual firm sizes is lower than in previous steps. Following this procedure, the total number of firm size groups is reduced from 50 to approximately 5 to 10 groups per growth barrier. The above discussion is summarized in Fig. 1 below.Footnote 13

Structure of method for assigning firm size groups. Note: Firm size increments are not represented to scale. The method for assigning firm size groups is based on their statistical relationship (weighted adjusted R2) to a given outcome variable. The developed method cycles through all consecutive firm size groups, ranging from 0 to 249 employees, i.e., 0–1, 0–2, 0–3, (…), 0–249 employees. The code needed to replicate the presented steps in STATA can be found in Appendix 4

The above approach is chosen over competing strategies, such as restricted cubic regression splines, as the latter (ideally) require knowledge of inflection points on beforehand. Moreover, their estimates are determined mainly by the number of inflection points included in the analysis rather than their absolute position (e.g., Harell 2015). Due to this, regression splines are likely unsuitable for the purposes of the current analysis.

Lastly, although the current application concerns perceived firm growth barriers, the method developed in this section is general and can be applied to a variety of empirical settings. Prominently, the presented method provides a versatile tool for solving a common methodological issue in research on entrepreneurship and small business, i.e., how to assign discrete firm size groups. This capability is likely to be of particular use for exploratory settings where there is little or no prior theory nor evidence to guide researchers in their empirical design. Through this, the presented strategy does also contribute to an emerging interest in using data-driven methods to study firm growth (Miyakawa et al. 2017; Coad and Srhoj 2019).

4.4 Control variables

Having identified the model’s dependent variables and having developed a method for assigning firm size groups, the task remains to identify its control variables.

4.4.1 Firm-level control variables

The first control that is included is firm age (Firm age), which refers to self-reported firm age as stated by top managers. Firm age is known to correlate with firm growth and size, meaning that it is likely to also correlate with perceived growth barriers (Coad et al. 2013; Lee and Cowling 2014; Coad 2018). Next, regional conditions are likely to affect the nature and conditions of business (Krugman 1991; Ciccone and Hall 1996). Therefore, the geographical location of each firm is controlled for in terms of counties, including a total of 21 regions (Region).Footnote 14 Business conditions are also likely to differ across industries. Therefore, the industry of each firm (Industry) is controlled for on the three-digit level in accordance with revision 2 of the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE rev. 2).

Furthermore, research suggests that firm conditions are likely to differ depending on whether a firm is independent or part of a larger organization (Delmar et al. 2003; Buckley and Casson 2007; Mahmood et al. 2016). Therefore, it is controlled for whether a firm is part of an enterprise group (Enterprise group) or a franchise (Franchise). Being part of an enterprise group is controlled for using a dummy variable, assuming the value “1” if a firm is part of an enterprise group and “0” otherwise. Franchise management is controlled for in two respects; whether a firm is part of a franchise and, if so, whether it is part of a foreign or domestic franchise. Lastly, the prevalence of firm growth barriers is likely to differ across time, such as across business cycles. Therefore, the timing of each survey is controlled for (Year).

4.4.2 Top manager control variables

Previous studies suggest that the gender of top managers is likely to affect which factors they perceive to impede growth (e.g., Orser and Hogarth-Scott 2002; Kwong et al. 2012). Accordingly, the gender of each top manager is controlled for (Female).

Next, top managers that belong to ethnic minorities have previously been found to be more likely than others to face growth barriers, in particular with respect to accessing finance (Aldén and Hammarstedt 2016; Clark et al. 2017). Therefore, the ethnicity of each top manager is controlled for in terms of whether they were born in Sweden or abroad (Immigrant).

4.4.3 Alternative measures of firm size

To benchmark the performance of the developed identification strategy, this measure is to be compared with the performance of commonly used size measures from the empirical literature on perceived growth barriers. To identify these measures, the previous literature is reviewed. Following this exercise, a total of 69 studies are identified, of which 14 are qualitative and 55 are quantitative. Once identified, all articles are reviewed for measures of firm size.

A substantial share of the identified studies do not address firm size, a total of 29 studies (close to half). These studies include case studies and descriptive analyses. Meanwhile, the most common way to measure firm size is in terms of the number of employees, a total of 12 studies (17%). In practice, this measurement implies the use of a continuous estimator. Next, the second and third most common ways of measuring firm size are by use of the OECD (2005) definition, i.e., by assigning firms into the categories of 0–9 employees (micro), 10–49 employees (small), 50–249 employees (medium-sized), and more than 250 employees (large), or by the World Bank (2001) definition, i.e., 5–50 employees (small), 51–500 employees (medium), and more than 500 employees (large), a total 4 studies each (6%, respectively).

A total of 20 studies use measures that are specific to only one or two articles (almost one-third). Because these measures do not recur in the literature, they will not be included in the analysis. Most of these measures are, however, similar to the OECD (2005) and World Bank (2001) definitions, meaning that conclusions derived for them are also likely to apply to other definitions.

The analysis in this section suggests that three measures of firm size are predominant in the empirical literature on perceived growth barriers: the total number of employees (continuous estimator), the OECD (2005) definition, and the World Bank (2001) definition. Based on this, these measures are selected to be used as benchmarks for the performance of the method developed in this article.Footnote 15

4.5 Evaluating model performance

To evaluate the performance of each respective size measure, the measures are compared in terms of McFadden’s pseudo R2 (McFadden 1973). For additional robustness, pseudo R2 is also calculated using Tjur’s D (Tjur 2009). These strategies are chosen over alternative approaches, such as Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) or the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), as these latter methods are based on parsimonious principles, i.e., they seek model simplicity, which is not necessarily an aim of the current article.Footnote 16

4.6 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and definitions for the included variables. As shown in Table 1, the typical (median) top manager is a male who was born in Sweden. Moreover, the typical firm is an independent firm that was established 12 years ago and has four employees.

Next, it is noted that the two most common growth barriers concern recruitment and regulations, where approximately 27 and 24% of top managers face these growth barriers, respectively. The fact that these two barriers are the most common is perhaps to be expected. Swedish firms have previously been noted to face high regulatory burden compared with other OECD firms, where the primary source of these liabilities has been linked to legislation on labor and recruitment practices (Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth 2018a, b; OECD 2018a, b). The third most commonly cited growth barrier is that of competition, which constitutes a substantial growth barrier for approximately 21% of all top managers.

In contrast to the above, additional findings shown in Table 1 suggest that a relatively low share of the surveyed firms face barriers relating to credit, consumer demand, equity financing, plant capacity, and profits—between approximately 8 and 13%. The fact that relatively few managers face financing constraints is notable given that this factor constitutes the most commonly cited growth barrier throughout the literature (e.g., Beck et al. 2005; Wang 2016; Mol-Gómez-Vázquez et al. 2019). This finding can likely be partially explained from the supply of small business financing. Sweden and the EU recently introduced a number of small business credit programs, which can be expected to have significantly alleviated the overall financing constraints of the sector (European Commission 2013).Footnote 17 These policy initiatives have also been coupled with innovations in banking, where financial institutions have been noted to use mixed loan structures consisting of both soft and hard lending technologies to successfully overcome small firm information asymmetries (e.g., Hernández-Cánovas and Martínez-Solano 2010; Beck et al. 2011; Cucculelli et al. 2019).

5 Results

In this section, the relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm size is explored. First, all growth barriers are analyzed jointly using the developed identification strategy. Thereafter, the discussion is narrowed to barriers that have particularly strong relationships to firm size, where estimates are compared with those yielded using a continuous estimator, the OECD (2005) definition and the World Bank (2001) definition of firm size. Lastly, the performance of the applied methods is evaluated in terms of pseudo R2.

5.1 Perceived growth barriers and firm size

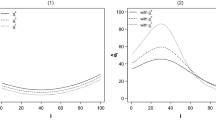

Figure 2 presents results on all analyzed perceived growth barriers and their relationship to firm size using the developed identification strategy. For illustrative purposes, the results have been divided into three graphs; Fig. 2 a, b, and c, respectively. As shown in the Fig. 2 b and c, five out of eight growth barriers are only marginally related to firm size. These barriers are those that concern access to credit, demand, plant capacity, profits, and regulations.Footnote 18 For the sake of brevity, these results will be discussed first, after which the remaining growth barriers, i.e., competition, equity financing, and recruitment, as depicted in Fig. 2a, will be studied in greater depth based on their particularly strong relationships to firm size.

Results of probit analysis, marginal effects estimates (∂y/∂x). Probability for top managers to perceive competition, access to credit, demand, access to equity financing, plant capacity, recruitment, or regulations to be a significant growth barrier, across firm size. For 2011, 2014, and 2017. a Marginal effect estimates. Probability that top managers will perceive competition, access to equity financing, or recruitment as significant growth barriers, across firm size. b Probability that top managers will perceive a lack of consumer demand, access to credit or current plant capacity as significant growth barriers, across firm size. c Probability that top managers will perceive regulations or a lack of profits as significant growth barriers, across firm size. Marginal effect estimates. Probability that top managers will perceive competition, access to credit, demand, access to equity financing, plant capacity, profits, recruitment, or regulations as significant growth barriers, across firm size. Estimates are adjusted for the gender and ethnicity of top managers, as well as the age, enterprise group affiliation, franchise affiliation, industry, and geographical location (county) of firms. Finally, estimates are also controlled for the year of observation

The results of Fig. 2b suggest that there are only marginal differences in credit constraints across firm size, where differences in the likelihood of facing this growth barrier range between 0 and 3% across groups. Therefore, the results shown in Fig. 2b seem to largely corroborate the previous statements that Swedish small businesses have access to a relatively abundant supply of credit financing.

Furthermore, the results of Fig. 2b suggest that firms with 85–91 employees are approximately 14% more likely to face growth barriers relating to a lack of consumer demand than are firms with fewer than 61 employees. This finding is in accordance with previous studies, although the majority of prior findings lack statistical significance (Robson and Obeng 2008; Coad and Tamvada 2012; Lee and Cowling 2014, 2015). While it is interesting in its own merit, however, this finding is perhaps most noteworthy when compared with equivalent ad hoc estimates, where the OECD (2005) and World Bank (2001) definitions of firm size completely obscure the observed differences.

The results shown in Fig. 2b suggest that firm size is weakly related to perceived growth barriers regarding plant capacity, where the largest difference across firm sizes constitutes approximately 6%. The fact that plant capacity constraints are weakly related to firm size is perhaps to be expected given that these concepts are more likely to be linked to geographical conditions, e.g., firm and population density, than to the size of individual firms (e.g., Krugman 1991; Ciccone and Hall 1996; Lee and Cowling 2015).

Next, the results of Fig. 2c suggest a weak relationship between firm size and perceived growth barriers regarding profit, where the largest difference across firm sizes constitutes approximately 5%. The fact that profit constraints do not differ across firm size is notable, given the otherwise strong support in favor of a pervasiveness in liquidity and profitability issues among small firms (e.g., Oliveira and Fortunato 2006; Donati 2016). A plausible explanation for this lack of heterogeneity may be that many firms are not growth-oriented, and hence, the average profit requirement of firms may be very low (e.g., Storey 1994; Hansen and Hamilton 2011; Gherhes et al. 2016). Lastly, the findings suggest that there are no significant differences in regulatory constraints across firm size. This finding is consistent with prior findings (Beck et al. 2005; Lee and Cowling 2014; Lee 2014; Lee and Cowling 2015). Therefore, the results shown in Fig. 2 do not seem to support the anecdotal observation that small firms are disproportionately encumbered by regulatory pressure (e.g., Kitching 2006; Kitching 2015). A plausible explanation for this finding may be that the term “regulation” encompasses a wide array of growth barriers and, thus, the expression itself may contain considerable heterogeneity.

Three growth barriers are found to have relatively strong relationships with firm size, namely, those concerning competition, access to equity financing, and recruitment, as presented in Fig. 2a. For the remainder of this section, these barriers and their relationship to firm size are examined.

Figure 3 presents results for perceived growth barriers regarding competition using the applied strategies for measuring firm size, i.e., the developed identification strategy, a continuous estimator, and the OECD (2005) and World Bank (2001) definitions of firm size.

Results of probit analysis, marginal effects estimates (∂y/∂x). Probability that top managers will perceive competition to be a significant growth barrier, across firm size. For 2011 and 2014. Notes: Marginal effect estimates. Bootstrapped standard errors (500 subsamples). Probability for top managers to perceive competition to be a significant growth barrier (Competition). Estimates are adjusted for the gender and ethnicity of top managers, as well as with the age, enterprise group affiliation, franchise affiliation, industry, and geographical location (county) of firms. Finally, estimates are also controlled for the year of observation. Firm sizes are grouped by firms with 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–40, 41–55, 56–75, 76–80, 81–91, 92–144, 145–153, and 154–249 employees. The OECD (2005) definition assigns firms into the categories of 0–9 employees (micro), 10–49 employees (small), 50–249 employees (medium), and 250 employees and more (large). The World Bank (2001) definition assigns firms into the categories of 5–49 employees (small), 50–500 employees (medium), and more than 500 employees (large). The presented continuous estimator constitutes a marginal effect estimate for one polynomial of firm size. Reference group using the developed identification strategy: firms with 0–4 employees. Reference group for OECD (2005) definition of firm size: firms with 0–9 employees. Reference group for the World Bank (2001) definition of firm size: firms with 0–4 employees. Reference group for the continuous estimator: firms with 0 employees

Applying the developed identification strategy reveals that the likelihood of encountering growth barriers from competition increases incrementally with firm size. The first of these increments is found for firms with 5–9 employees, who are approximately 5% more likely to face this barrier compared with those with 0–4 employees. Next, this likelihood is found to further increase for firms with 10–14 employees, where these firms are significantly more likely to face this barrier compared with those with 0–4 and 5–9 employees, approximately 9 and 3%, respectively.

Next, by analyzing larger firm sizes, it is found that the likelihood of perceiving competition as a growth barrier is significantly higher among firms with 41–55 employees than among those with 0–4, 5–9, and 10–14 employees. These firms are found to be approximately 12, 7, and 4% more likely to face this barrier compared with the aforementioned firms. Lastly, firms with 76–144 employees are found to be more likely than the abovementioned groups to face growth barriers from competition. These firms are approximately 26, 20, 17, and 9% more likely to face this growth barrier compared with those with 0–4, 5–9, 10–14, and 41–55 employees.

Furthermore, by applying a continuous estimator of firm size, a positive relationship is identified, where a 1% increase in employment is found to be associated with a 3% increase in the likelihood to face growth barriers from competition. Conversely, by applying the OECD (2005) definition of firm size, it is found that firms with 10–49 and 50–249 employees are 9, versus 21% more likely to face this barrier, compared with those with 0–9 employees. Lastly, by applying the World Bank (2001) definition of firm size, it is found that firms with 5–50 employees and 51–249 employees are approximately 9, versus 23% more likely to face barriers from competition, compared with those with 0–4 employees.

A striking feature of Fig. 3 is the similarity in magnitudes among the three discontinuous measures of firm size, i.e., the developed identification strategy, the OECD (2005), and the World Bank (2001) definitions. At first sight, this similarity may seem to speak in favor of using ad hoc firm size measures as they are both relatively simplistic and produce point estimates comparable with the developed identification strategy. However, although the estimates themselves are similar, a critical distinction among the three strategies concerns the level of detail in which their respective predictions are made. In this respect, the identification strategy proposed here is argued to widely outperform the two other discontinuous strategies as it allows researchers to make detailed predictions on the specific size thresholds where firms incur growth barriers (i.e., 5–14 versus 41–55 and 76–144 employees) rather than to simply estimate their prevalence across generic groups, as occurs in the latter cases (i.e., 5–50 and 10–49 employees versus 51–249 and 50–249 employees). Furthermore, this increased precision in the discussion of firm size is arguably central for furthering our understanding of firm growth barriers and their antecedents.

The overall results of Fig. 3 are consistent with discussions in the strategic management literature, which suggest that larger firms are more likely than smaller ones to diversify their activities and to expand into new markets (Grossmann 2007; Benito-Osorio et al. 2015). Meanwhile, expansion into new markets is, in turn, thought to be associated with increased competition and substantial entry costs (e.g., Hölzl 2012). In contrast, the results are in opposition to those of Wang (2016), who found a negative relationship between competition barriers and firm size. However, these estimates were only obtained for SMEs as a group relative to larger firms, for which they are likely to contain a considerable degree of unobserved heterogeneity. Moreover, this difference is likely further exacerbated by differences in institutional context, as Wang (2016) studied firms in developing economies.

Figure 4 presents results on perceived growth barriers related to a lack of access to equity financing.

Results of probit analysis, marginal effects estimates (∂y/∂x). Probability for top managers to perceive a lack of access to equity financing to be a significant growth barrier, across firm size. For 2011, 2014, and 2017. Notes: Marginal effect estimates. Bootstrapped standard errors (500 subsamples). Probability for top managers to perceive a lack of access to equity financing to be a significant growth barrier (Financing). Estimates are adjusted for the gender and ethnicity of top managers, as well as the age, enterprise group affiliation, franchise affiliation, industry, and geographical location (county) of firms. Finally, estimates are also controlled for the year of observation. Firm sizes are grouped by firms with 0–2, 3–14, 15–19, 20–40, 41–60, 61–70, 71–91, 92–145, and 146–249 employees. The OECD (2005) definition assigns firms into the categories of 0–9 employees (micro), 10–49 employees (small), 50–249 employees (medium), and 250 employees and more (large). The World Bank (2001) definition assigns firms into the categories of 5–49 employees (small), 50–500 employees (medium), and more than 500 employees (large). The presented continuous estimator constitutes a marginal effect estimate for two polynomials of firm size. Reference group using the developed identification strategy: firms with 0–2 employees. Reference group for OECD (2005) definition of firm size: firms with 0–9 employees. Reference group for the World Bank (2001) definition of firm size: firms with 0–4 employees. Reference group for the continuous estimator: firms with 0 employees

By applying the developed identification strategy, it is found that firms with 0–2, 3–14, and 15–19 employees are approximately 3–4% more likely to face equity financing constraints compared with those with 41–60, 61–70, 71–91, 92–145, and 146–249 employees. In addition, it is found that firms with 20–40 employees are approximately 7% more likely to face this growth barrier compared with those with 146–249 employees.

Next, by applying a continuous estimator of firm size, a negative relationship is identified, where a 1% increase in employment is, on average, associated with an approximately 0.3% decrease in the likelihood to face growth barriers related to equity financing. Furthermore, by applying the OECD (2005) definition of firm size, it is found that firms with 50–249 employees are approximately 4% less likely to face this barrier compared with firms with 0–9 and 10–49 employees. Lastly, by applying the World Bank (2001) definition of firm size, firms with 5–50 and 51–249 employees are found to be more 1% more likely, versus 4% less likely, to face this growth barrier compared with those with 0–4 employees.

A prominent finding of Fig. 4 is the strong resemblance among point estimates using the three discontinuous strategies for measuring firm size. This consistency is, in turn, similar to the findings shown in Fig. 3. However, although the applied strategies produce similar point estimates, it is again noted that there are considerable differences in their respective abilities to capture firm size heterogeneity. In this regard, the developed identification strategy is argued to outperform its other discrete counterparts as it is able to account for the same mechanisms as the latter while also being able to produce detailed predictions on the size thresholds at which firms incur, versus overcome growth barriers. Specifically, findings using the proposed identification strategy suggest that perceived equity financing constraints are the most pervasive among firms in the range of 0–19 employees. This finding stands to be compared with the findings of ad hoc groups, which instead attribute this prevalence to a considerably wider and generic set of firm sizes, i.e., 0–50 or 0–49 employees. Based on this difference, the proposed identification strategy is argued to be more suitable for studying perceived equity financing constraints as it allows researchers to make substantially more detailed predictions on their nature and heterogeneity.

The results of Fig. 4 are in accordance with theory on financial accessibility, which predicts that small firms are more likely than larger ones to face financing issues due to adverse selection on the financial market (e.g., Berger and Udell 1998; Cenni et al. 2015). These findings are also consistent with related empirical findings, although the latter have identified the corresponding relationships for considerably wider spans of firm sizes (e.g., Beck et al. 2005; Wang 2016; Lee and Luca 2019). The results shown in Fig. 4 are consistent with Beck et al. (2005), who found that firms with 5–50 and 51–500 employees were approximately 29—versus 23—percent more likely to face financing constraints compared with those with more than 500 employees.

In contrast to the above, however, the results shown in Fig. 4 suggest that there is substantial heterogeneity within the group of 5–50 employees. This heterogeneity raises questions as to what extent the findings of Beck et al. (2005) are driven by financing constraints across the full 5–50 employee size range versus the extent to which they are a result of empirical limitations. Given the prevalent use of ad hoc measures in research and policy analysis of financial constraints, this latter distinction is likely to hold considerable practical implications.

Figure 5 presents the results for perceived growth barriers related to recruitment. Applying the developed identification strategy reveals that the likelihood to face recruitment issues increases sharply among firms with 3–14 and 15–19 employees relative to those with 0–2 employees, while remaining relatively constant across those with between 20 and 40 employees. Firms with 3–14, 15–19, and 20–40 employees are found to be approximately 16–17% more likely to face recruitment issues compared with those with 0–2 employees. In addition, this likelihood is found to increase for firms with 41–249 employees, where the latter are found to be approximately 13% more likely to face growth barriers related to recruitment, compared with those with 0–19 employees.

Results of probit analysis, marginal effects estimates (∂y/∂x). Probability for top managers to perceive issues related to recruiting staff to be a significant growth barrier, across firm size. For 2011, 2014, and 2017. Notes: Marginal effect estimates. Bootstrapped standard errors (500 subsamples). Probability for top managers to perceive issues related to recruiting staff to be a significant growth barrier (Recruitment). Estimates are adjusted for the gender and ethnicity of top managers, as well as the age, enterprise group affiliation, franchise affiliation, industry, and geographical location (county) of firms. Finally, estimates are also controlled for the year of observation. The derived size measure assigns firms into the categories of 0–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–40, and 41–249 employees. The OECD (2005) definition assigns firms into the categories of 0–9 employees (micro), 10–49 employees (small), and 50–249 employees (medium). The World Bank (2001) definition assigns firms into the categories of 5–50 employees (small) and 51–249 employees (medium). The presented linear estimates include three polynomials of firm size

Here, it is worth noting that the findings shown in Fig. 5 largely mirror those of Fig. 4 regarding access to equity financing, although with reverse signs. It is possible that these results reflect the same relationship, i.e., changes in firm constraints over their lifecycle, where financing is more likely to be a binding constraint for smaller firms than for larger ones. In turn, once firms exceed a certain size, factors such as competence are more likely to be a prominent constraint.

Next, by applying a continuous estimator of firm size, a positive relationship is identified, where a 1% increase in firm employment is, on average, associated with a 6% increase in the likelihood of facing recruitment issues. Conversely, by applying the OECD (2005) definition, firms with 10–49 employees and 50–249 employees are found to be approximately 10, versus 26% more likely to face this growth barrier than those with 0–9 employees. Finally, by applying the World Bank (2001) definition, it is found that firms with 5–50 and 51–249 employees are approximately 14 and 28% more likely to face growth barriers related to recruitment compared with those with 0–4 employees.

Similar to the preceding analyses, the results shown in Fig. 5 suggest a high degree of similarity in point estimates between the three discontinuous strategies for measuring firm size. Furthermore, it is again noted that there are considerable differences in the strategies’ abilities to capture size thresholds at which firms incur, versus overcome, growth barriers. In the case of Fig. 5, findings using the proposed identification strategy suggest that firms with at least 41 employees are more likely than those with 0–19 employees to face recruitment issues. Additionally, ad hoc groups are found to attribute the same outcomes to substantially wider size groups, i.e., to firms with 5–50 and 10–49 employees versus 51–249 and 50–249 employees. Following these results, the proposed identification strategy is again argued to outperform its ad hoc equivalents as it is able to capture the studied mechanisms in considerably greater detail than the latter.

The results of Fig. 5 are consistent with the findings of Lee and Cowling (2015), who identified a positive relationship between firm size and the likelihood of facing recruitment issues. They found that firms with 0–49 employees were significantly less likely to face this growth barrier compared with those with 50 employees or more. Given the results of Fig. 5, it is possible that their results reflect the same relationships as observed here, although the use of ad hoc size groups may have restricted their ability to identify heterogeneity within the 0–49 employee firm size interval.

5.2 Model performance

To formally evaluate the performance of the applied strategies for measuring firm size, each approach is also evaluated in terms of its model fit. Table 2 presents findings on the performance of each strategy, measured as their corresponding models’ predictive power (McFadden’s pseudo R2).

As shown, the proposed identification strategy yields the highest performance in terms of pseudo R2 for a majority of barriers. In two cases, for competition and recruitment, it is found that a continuous estimator of firm size yields a higher explanatory power. A likely reason for this finding is that these variables involve relatively linear relationships with firm size, which a continuous estimator of firm size is able to capture without the discrete shifts employed by other strategies. However, given the limitations of a continuous estimator, i.e., a generally low precision in estimates for larger firms, this strategy may prove difficult to implement in practice.

A central finding shown in Table 2 concerns the fact that the developed identification strategy consistently outperforms the other two discrete strategies in measuring firm size. Therefore, these results appear to corroborate the statements made above in this article, i.e., that the proposed identification strategy can capture the relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm size in considerably greater detail than its ad hoc equivalents.

As a robustness analysis, the predictive power of each model is also presented in terms of Tjur’s D, which is given in parentheses. The results seem to be robust across methods for calculating pseudo R2. The results change in only one case, namely, for recruitment, where the developed identification strategy is found to perform worse than the other measures in explaining this outcome.

Finally, a relevant concern is whether the results of Table 2 are driven by the inclusion of additional regressors. The proposed identification strategy employs a marginally higher number of control variables than the other measures, which may increase its explanatory power due to spurious correlation. However, this relationship is likely to have only a marginal influence on the results for two reasons. First, by including a number of determinants of firm growth, such as the firm’s age, industry, location, and ownership, the analysis drastically reduces the number of exogenous factors that are likely to influence this relationship. Next, the developed identification strategy is noted to favor relatively simplistic models over more intricate ones. In contrast, if the influence of spurious correlation were considerable, it would instead tend to select group numbers close to its theoretical maximum. Hence, based on this, it is argued that the results of Table 2 are explained by an increased precision in identifying firm size heterogeneity rather than by spurious correlation.

6 Concluding remarks

This article shows that perceptions of firm growth barriers differ considerably across firm size. Furthermore, the results suggest that the choice of empirical strategy for measuring firm size is instrumental in shaping the way in which we conceptualize perceived growth barriers and their antecedents.

The application of a novel, data-driven strategy for identifying firm size groups to a dataset covering approximately 44,000 Swedish SMEs (0–249 employees) reveals that smaller firms typically face constraints on equity financing, whereas larger firms generally face barriers regarding competition and recruitment. Next, as a benchmark, these results are compared with those yielded by using a continuous estimator of firm size as well as standardized, so-called “ad hoc,” definitions of firm size following the nomenclatures of the OECD (2005) and the World Bank (2001). The results show that the proposed identification strategy widely outperforms its ad hoc equivalents in that it is able to account for the same dynamics as the latter while also yielding considerably more detailed predictions on the size thresholds at which firms incur, versus overcome, growth barriers. In contrast, ad hoc groups are found to consistently overshoot the abovementioned thresholds, whereby they fail to account for relevant size heterogeneity. Lastly, it is concluded that the use of a continuous estimator generally constitutes the second-best option among the applied strategies.

While the findings of this article are consistent with previous empirical research, it improves substantially on the former by capturing the relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm size in considerably greater detail. Most closely related to this article is that of Beck et al. (2005), who established that firms with 5–50 employees are more likely than larger firms to face financing constraints. This article supports their findings, although it is also concluded that there is substantial heterogeneity within the abovementioned group, i.e., firms with 5–50 employees. This finding raises questions as to the extent to which their findings are the consequences of financial constraints across the full 5–50 employee size range versus the extent to which they are the result of empirical limitations.

One limitation of this article is that it is based on perceptions, whereby the subjective nature of the studied phenomena may give rise to endogeneity issues. Prominently, growth rates and growth ambitions are known to differ across firm size. Furthermore, both of these factors are likely to affect top managers’ perceptions of firm growth barriers. To evaluate these issues, robustness analyses have been conducted to examine the role of self-stated growth ambitions and future growth expectations in perceived growth barriers across firm size. The outcomes of these analyses suggest that these factors have limited influence on the study’s results, whereby perceptions by top managers are inferred to be a valid measure for the purpose of the current analyses.Footnote 19

A second limitation concerns the fact that perceptions are unlikely to be fully comparable across individuals. Nevertheless, by using large-scale data and by controlling for a number of firm and top manager characteristics, the influence of differences across individual top managers is arguably reduced. A third limitation of this article concerns the fact that it covers only one institutional context—Sweden—where it purposely seeks to fit a regression model to the specific data used. A relevant concern is therefore whether its results are generalizable to other regions and time periods. Nonetheless, by conducting robustness checks over individual years and by comparing the results of this study with those of previous research, it is found that the overall implications are stable across the former. Moreover, the Swedish firm population has previously been noted to be similar to that of other western economies, which further speaks in its merit (e.g., Anyadike-Danes 2015; Andersson et al. 2018). A fourth limitation concerns the fact that the current analysis may be partially driven by sectoral differences in firm size. However, given that the sample is drawn to represent the full distribution of Swedish firms across industries, regions, and sizes, these sectoral differences can nonetheless be expected to closely correspond to those of the aggregate economy.

The findings suggest a need to rethink the treatment of firm size in empirical research on firm growth barriers. Specifically, the findings suggest that ad hoc firm size groups may be unsuitable for analyzing perceived firm growth barriers. Lastly, the findings notably suggest that ad hoc groups fail to capture dynamics among firms with up to 19 employees, whereby this group may be of particular interest to future research design.

For future research, a natural extension of this work may be to apply an equivalent empirical framework to study perceived growth barriers for different geographical and institutional contexts, as well as for specific economic sectors. With this approach, researchers may ultimately obtain new and deeper insights on the relationship between perceived growth barriers and firm size.

Notes

Within the confines of this paper, these groups are referred to ad hoc in the sense that they are not designed with the intention of studying firm growth barriers but, rather, to yield a general rule for categorizing firm sizes.

Throughout the article, the expressions “to perceive” and “to face” are used interchangeably to describe whether top managers identify a certain factor to be a growth barrier. Moreover, for the sake of brevity, the terms “top manager” and “firm” are used interchangeably to describe the occurrence of growth barriers within firms.

Specifically, the largest available multinational dataset on perceived growth barriers constitutes that of the World Bank Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Surveys (BEEPS), which currently cover approximately 120 economies. Due to its low coverage of each economy, however, the BEEPS has limited support for within-country firm size decompositions and thus is likely unsuitable for the purpose of the current analysis.

The surveyed population is delimited to private and domiciled sole proprietorships, partnerships, and limited liability firms (excluding the financial sector). This corresponds to approximately 90% of all Swedish firms.

Previous survey waves have been conducted in 2002, 2005, and 2008. However, they are not comparable with the later studies and are therefore omitted.

The formulations of these questions, as stated in the questionnaire, are presented in Appendix 1.

As a robustness check, analyses have also been conducted based on whether or not top managers face moderate or significant growth barriers. The outcomes of these analyses suggest that the results of the study are robust, although they become less pronounced when including “moderate” growth barriers.

Four variables are omitted from the analysis because their definitions have changed over the years, including growth barriers related to access to infrastructure, broadband, transport systems, and time for planning and strategizing. Robustness analyses suggest that these variables are only marginally related to firm size.

A person is considered employed within a firm if that person has collected labor and/or business income equivalent to 20% of a full-time occupation (32 h per month), which is the standard definition used by Statistics Sweden.

Distributional plots across firm size in terms of the number of respondents and their respective growth barriers can be found in Appendix 3.

The motivation for using a linear estimation model (specifically, OLS) is that these models enable the use of adjusted R2 to evaluate model fit. This approach is preferable to non-linear goodness-of-fit statistics as the latter are less agreed upon and carry less intuitive value.

Specifically, the model fit of each firm size group is weighted by the Kernel density of firms at its upper size limit, i.e., at its upper Kernel bandwidth. For example, in evaluating groups covering firms with 0–10 employees, regression output is weighted by the estimated Kernel density of firms with 10 employees.

The code needed to replicate the presented steps in STATA can be found in Appendix 4.

For a firm operating in multiple counties, this refers to the county where its head office is situated.

A complete list of the identified studies is presented in Appendix 2.

Similarly to AIC and BIC, the adjusted McFadden’s pseudo R2 is rejected due to its underlying parsimonious principles. Robustness analysis using the adjusted McFadden’s pseudo R2 suggests that this delimitation does not change the study’s overall results, although it does prioritize linear models to a higher extent than its unadjusted counterpart, which is likely due to their relative simplicity.

Similar public credit guarantee programs have also been implemented in the U.S. (e.g., U.S. Small Business Association 2019).

Results are available from the author upon request.

References

Anyadike-Danes, M., Bjuggren, C. M., Gottschalk, S., Holzl, W., Johansson, D., Maliranta, M., et al. (2015). An international cohort comparison of size effects on job growth. Small Business Economics, 44(4), 821–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9622-0.

Aldén, L., & Hammarstedt, M. (2016). Discrimination in the credit market? Access to financial capital among self-employed immigrants. Kyklos, 69(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12101.

Andersson, F. W., Johansson, D., Karlsson, J., Lodefalk, L., & Poldahl, A. (2018). The characteristics of family firms: Exploiting information on ownership, kinship, and governance using total population data. Small Business Economics, 51(3), 539–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9947-6.

Audretsch, D. B., & Elston, J. A. (2002). Does firm size matter? Evidence on the impact of liquidity constraints on firm investment behavior in Germany. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-7187(00)00072-2.

Beck, T., & Demirgüc-Kunt, A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(11), 2931–2943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.009.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2005). Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter? The Journal of Finance, 60(1), 137–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00727.x.

Beck, T., Dermigüc-Kunt, A., & Pería, M. (2011). Bank financing for SMEs: Evidence across countries and bank ownership types. Journal of Financial Services Research, 39(1–2), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-010-0085-4.

Benito-Osorio, D., Colino, A., & Zúñiga-Vicente, J. Á. (2015). The link between product diversification and performance among Spanish manufacturing firms: Analyzing the role of firm size. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 32(1), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1303.

Berger, A., & Udell, G. (1998). The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22(6), 613–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00038-7.

Birch, D. L. (1979). The job generation process. Michigan: MIT Program on Neighborhood and Regional Change. Available at SSRN https://ssrn.com/abstract=1510007.

Bornhäll, A., Daunfeldt, S.-O., & Rudholm, N. (2017). Employment protection legislation and firm growth: Evidence from a natural experiment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 26(1), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtw017.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. (2007). Edith Penrose’s theory of the growth of the firm and the strategic management of multinational enterprises. MIR: Management International Review, 47(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-007-0009-1.

Cenni, S., Monferrà, S., Salotti, V., Sangiorgi, M., & Torluccio, G. (2015). Credit rationing and relationship lending. Does firm size matter? Journal of Banking & Finance, 53, 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.12.010.

Ciccone, A., & Hall, R. e. (1996). Productivity and the density of economic activity. The American Economic Review, 86(1), 54–70 Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118255.

Clark, K., Drinkwater, S., & Robinson, C. (2017). Self-employment amongst migrant groups: New evidence from England and Wales. Small Business Economics, 48(4), 1047–1069. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9804-z.

Coad, A. (2018). Firm age: A survey. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 28(1), 13–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-016-0486-0.

Coad, A., & Hölzl, W. (2012). Firm growth: Empirical analysis. In M. Dietrich & J. Krafft (Eds.), Handbook on the economics and theory of the firm. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781848446489.00035.

Coad, A., Segarra, A., & Teruel, M. (2013). Like milk or wine: Does firm performance improve with age? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 24, 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2012.07.002.

Coad, A., & Srhoj, S. (2019). Catching gazelles with a lasso: Big data techniques for the prediction of high-growth firms. Small Business Economics (forthcoming). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00203-3.

Coad, A., & Tamvada, J. P. (2012). Firm growth and barriers to growth among small firms in India. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9318-7.

Cucculelli, M., Peruzzi, V., & Zazzaro, A. (2019). Relational capital in lending relationships: Evidence from European family firms. Small Business Economics, 52(1), 277–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0019-3.

Davidsson, P., Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2006). Entrepreneurship and the growth of firms. Aldershot: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781009949.

Delmar, F. (1997). Measuring growth: Methodological considerations and empirical results. In R. Donckels & A. Miettinen (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and SME research: On its way to the next millenium (pp. 190–216). Aldershot: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781009949.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. B. (2003). Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 189–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00080-0.

Donati, C. (2016). Firm growth and liquidity constraints: Evidence from manufacturing and service sectors in Italy. Applied Economics, 48(20), 1881–1892. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2015.1109044.

European Commission. (2013). Entrepreneurship and innovation programme EIP performance report. Brussels: European Commission.

Gherhes, C., Williams, N., Vorley, T., & Vasconcelos, A. (2016). Distinguishing micro-businesses from SMEs: A systematic review of growth constraints. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(4), 939–963. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-05-2016-0075.

Gilbert, B. A., Audretsch, D. B., & McDougall, P. P. (2004). The emergence of entrepreneurship policy. Small Business Economics, 22(3/4), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SBEJ.0000022235.10739.a8.

Grossmann, V. (2007). Firm size and diversification: Multiproduct firms in asymmetric oligopoly. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 25(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2005.12.003.

Hansen, B., & Hamilton, R. (2011). Factors distinguishing small firm growers and non-growers. International Small Business Journal, 29(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610381846.

Harell, F. (2015). Regression modeling strategies. New York: Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7.

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (1999). Institutional effects on the evolution of the size distribution of firms. Small Business Economics, 12(1), 11–23 https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008002330051.

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (2010). Gazelles as job creators: A survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 35(2), 227–244 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9172-z.

Henrekson, M., & Stenkula, M. (2010). Entrepreneurship and public policy. In Z. J. Acs & D. B. Audretsch (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurship research (Vol. 5). New York: Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1191-9.

Hernández-Cánovas, G., & Martínez-Solano, P. (2010). Relationship lending and SME financing in the continental European bank-based system. Small Business Economics, 34(4), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9129-7.

Hölzl, W. (2012). Mobility barriers and the speed of market selection. WIFO working papers (no. 437). Vienna: WIFO.

Kitching, J. (2006). A burden on business? Reviewing the evidence base on regulation and small-business performance. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 24(6), 799–814. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0619.

Kitching, J. (2015). Burden or benefit? Regulation as a dynamic influence on small business performance. International Small Business Journal, 33(2), 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613493454.

Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing returns and economic geography. Journal of Political Economy, 99(3), 483–499. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1505245

Kwong, C., Jones-Evans, D., & Thompson, P. (2012). Differences in perceptions of access to finance between potential male and female entrepreneurs: Evidence from the UK. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 18(1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551211201385.

Lee, N. (2014). What holds back high-growth firms? Evidence from UK SMEs. Small Business Economics, 43(1), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9525-5.

Lee, N., & Cowling, M. (2014). Place, sorting effects and barriers to enterprise in deprived areas: Different problems or different firms? International Small Business Journal, 31(8), 914–937. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242612445402.

Lee, N., & Cowling, M. (2015). Do rural firms perceive different problems? Geography, sorting, and barriers to growth in UK SMEs. Environment and Planning C – Government and Policy, 33(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1068/c12234b.

Lee, N., & Luca, D. (2019). The big-city bias in access to finance: Evidence from firm perceptions in almost 100 countries. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(1), 199–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbx047.

Levy, B. (1993). Obstacles to developing indigenous small and medium enterprises: An empirical assessment. World Bank Economic Review, 7(1), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/7.1.65.

Mahmood, I. P., Zhu, H., & Zaheer, A. (2016). Centralization of intragroup equity ties and performance of business group affiliates: Intragroup equity ties and business group affiliates. Strategic Management Journal, 38(5), 1082–1100. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2542.

McCann, P., & Ortega Argiles, R. (2016). Smart specialisation, entrepreneurship and SMEs: Issues and challenges for a results-oriented EU regional policy. Small Business Economics, 46(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9707-z.

McFadden, D. (1973). Conditional Logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In P. Zarembka (Ed.), Frontiers in econometrics (pp. 105–142). New York: Academic Press.

Miyakawa, D., Miyauchi, Y., & Perez, C. (2017). Forecasting firm performance with machine learning: Evidence from Japanese firm-level data. In RIETI discussion paper 17068. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI): Tokyo.

Mol-Gómez-Vázquez, A., Hernández-Cánovas, G., & Koëter-Kant, J. (2019). Bank market power and the intensity of borrower discouragement: Analysis of SMEs across developed and developing European countries. Small Business Economics, 53(1), 211–225 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0056-y.

Nyström, K., & Elvung, G. Z. (2014). New firms and labor market entrants: Is there a wage penalty for employment in new firms? Small Business Economics, 43(2), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9552-x.

OECD. (2005). OECD SME and entrepreneurship: 2005. Paris: OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264009257-en.

OECD. (2018a). Enhancing SME access to diversified financing instruments. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9150(99)80142-7.

OECD. (2018b). OECD regulatory policy outlook 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

Okpara, J. O. (2011). Factors constraining the growth and survival of SMEs in Nigeria. Management Research Review, 34(2), 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171111102786.

Okpara, J. O., & Wynn, P. (2007). Determinants of small business growth constraints in a sub-Saharan African economy. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 72(2), 24–36.

Oliveira, B., & Fortunato, A. (2006). Firm growth and liquidity constraints: A dynamic analysis. Small Business Economics, 27(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-0006-y.

Orser, B., & Hogarth-Scott, S. (2002). Opting for growth: Gender dimensions of choosing enterprise development. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 19(3), 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.2002.tb00273.x.

Orser, B. J., Hogarth-Scott, S., & Riding, A. L. (2000). Performance, firm size, and management problem solving. Journal of Small Business Management, 38(4), 42–58.

Palazuelos, E., Crespo, Á. H., & del Corte, J. M. (2018). Accounting information quality and trust as determinants of credit granting to SMEs: The role of external audit. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 861–877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9966-3.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198289774.001.0001.

Robson, P., & Obeng, B. (2008). The barriers to growth in Ghana. Small Business Economics, 30(4), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9046-1.

Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector. Andover: Cengage Learning. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315544335.

Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth. (2018a). Förenkla för företagen (Better Regulation for Swedish Firms). Stockholm: Agency for Economic and Regional Growth.

Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth. (2018b). Företagens villkor och verklighet 2017 (the situation and condition of enterprises 2017). Stockholm: Agency for Economic and Regional Growth.

Tjur, T. (2009). Coefficients of determination in logistic regression models—A new proposal: The coefficient of discrimination. The American Statistician, 63(4), 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1198/tast.2009.08210.

U.S. Small Business Administration. (2019). Small business administration 7(a) loan guaranty program (no. R41146). Washington D.C.: American Congress Research Service.

Wang, Y. (2016). What are the biggest obstacles to growth of SMEs in developing countries? – An empirical evidence from an enterprise survey. Borsa Istanbul Review, 16(3), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2016.06.001.

World Bank (2001). Firm size and the business environment: Worldwide survey results. International Finance Corporation Discussion Paper number 43. Washington D.C: The World Bank.

Acknowledgments