Abstract

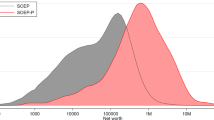

Entrepreneurs or small business owners are confronted by a number of risks in their business activities. Previous literature suggests that entrepreneurs balance business-related financial risk by changing their personal investment strategy to include fewer investments in risky stocks. However, existing studies cannot separate the effects of business-related financial risk from other household and individual factors that influence investment choices. A causal identification strategy is needed to provide actionable evidence regarding whether efforts to ease business-related financing limitations such as low-interest loan or venture capital programs are likely to influence entrepreneurial activity. This analysis uses instrumental variables (IV) estimation to isolate the effects of business ownership on personal finances. Results from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) suggest that entrepreneurs do mitigate business-related financial risk by reducing their personal portfolio share of risky financial assets, but at only half the magnitude estimated by previous studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Kanbur (1979), Kihlstrom and Laffont (1979), Bruce (2000, 2002), and Cullen and Gordon (2007) for examples of theoretical models. Vereshchagina and Hopenhayn (2009) develop a model of endogenous risk taking to explain why entrepreneurial returns, assumed to be inherently risky, do not receive a large risk premium. Their model suggests that entrepreneurs are relatively risk tolerant at the time of entrepreneurial entry.

Heaton and Lucas (2000b) reach analogous conclusions about background risks in general. Although not focused on differences between entrepreneurial and non-entrepreneurial households, research suggests that labor income risks (Guiso et al. 1996; Davis and Willen 2000), borrowing constraints (Guiso et al. 1996), and medical expenditures (Goldman and Maestas 2013) are important in determining portfolio allocations. Other factors affecting portfolio allocations include wealth and education (Bertaut 1998; Calvet et al. 2009).

Population weights were used to generate all statistics. Slight differences are likely between the statistics presented in this analysis and those presented in Bucks et al. (2009) because this analysis is limited to the public-use version of the data.

Data from 1989 are included for comparisons to earlier work but are excluded from the regression analyses due to the lack of availability of the IV variables for earlier time periods.

Note that while the patterns are generally consistent with Gentry and Hubbard (2004), the numbers differ because assets are defined differently. Assets are defined as in Bucks et al. (2009). Financial assets include transaction accounts, certificates of deposit, savings bonds, stocks, pooled investment funds, retirement accounts, cash value of life insurance, and other managed assets.

We note that some caution in interpreting the data is needed as there are key differences in how asset values are reported. Survey respondents are encouraged to use documents, including statements, when answering questions about financial assets. For business assets, respondents are asked how much they could sell their share of the business for, and for house value, respondents are asked what the property would be worth if sold today. These differences might affect the calculated portfolio shares across categories (e.g., higher than market estimates of business value will lead to lower calculated financial asset shares).

See Angrist and Pischke (2009) for more information on the omitted variables bias formula.

We use the STATA cmp command.

One way to address the limitation of having cross-sectional data that is not a panel is to treat the surveys as repeated cross-sections following recent SCF research (Sabelhaus and Pence 1999; Moore 2004). However, repeated cross-section estimation is a version of IV estimation (Moffitt 1993) and requires that all of the standard conditions are met (Verbeek and Vella 2005). Common groupings, such as age cohorts, are not an option for this analysis as the entrepreneurial decision is commonly associated with age and other potential grouping variables.

Results are comparable when age 35 is used to establish the IV values and when an average of IV values from 25 to 35 is used. Results are listed in Table 4.

Real interest rates are calculated using inflation rates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index.

Nominal interest rates are used in the regression analysis because a consistent CPI measure (CPI-RS) is only available back to 1978.

Note that the number of spousal siblings is truncated at 6 in the SCF data.

See Bracke et al. (2014), Fairlie (2013) and Wang (2012) for empirical evidence on home ownership and entrepreneurship. Papers examining housing and portfolio choice include Fratantoni (1998), Heaton and Lucas (2000b), Campbell and Cocco (2003), Cocco (2005), Chetty et al. (2017), and Yao and Zhang (2005). We expect the measure of home ownership to be subject to less reporting error and variation across respondents than alternative measures such as home equity or mortgage liability.

A limitation of our approach is the use of a linear model for a fractional dependent variable, which generates concerns about out-of-range predicted values or bias when means are near the extremes (Elsas and Florysiak 2015; Ramalho and Ramalho 2017; Murteira and Ramalho 2016; Ramalho et al. 2011). This concern around extreme values (i.e., means near zero) is mitigated because we are not using the model to predict outcomes and by our use of a selection equation. We rely on the best linear approximation of our estimator to generate similar results, akin to using a linear probability model for binary outcomes (Angrist and Pischke 2009).

Other candidates for control variables, such as income, health insurance status, and perceived labor income risk are excluded from the baseline specification as they are likely to be jointly determined with the covariate of interest, entrepreneurial status. Results remain the same when these variables are included.

Please see footnote 15. Mortgage debt is included as the natural log of mortgage debt (in $10,000). Home equity is included as the inverse hyperbolic sine (to allow for negative and zero values in $10,000).

The selection model addresses the concern that households likely have a reference point (e.g. $500, $1000, etc.) and do not invest in stocks when their risky asset allocation is below this threshold. Tobit models produce comparable results.

Specifically, the results are obtained from the Stata cmp command, which allows for the maximum likelihood estimation of a broad range of mixed process Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR) models (Roodman 2011).

The average age of respondents in the labor force is 46. Results approximate those without the labor force restriction.

Use of the fixed effects model is a key component of our identification strategy, although we note that the same limitations as using a linear model described in footnote 15 also apply.

Results are presented for weighted data. Adjusting estimates for the presence of multiple implicates as in Kennickell (2017) does not meaningfully alter the results for unweighted data.

The IV variables are jointly significant at the 1% level (Hansen J = 0.740, P value = 0.390).

Similar to Chetty et al. (2017), the coefficients are of opposing signs in which mortgage debt has a negative coefficient while home equity has a positive coefficient.

References

Anderson, A. R., Jack, S. L., & Dodd, S. D. (2005). The role of family members in entrepreneurial networks: beyond the boundaries of the family firm. Family Business Review, 18(2), 135–154.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. J. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ardagna, S., & Lusardi, A. (2008). Explaining international differences in entrepreneurship: the role of individual characteristics and regulatory constraints. In J. Lerner & A. Schoar (Eds.), International differences in entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Becker, T. A., & Shabani, R. (2010). Outstanding debt and the household portfolio. The Review of Financial Studies, 23(7), 2900–2934.

Bergerab, A. N., & Udellc, G. F. (1998). The economics of small business finance: the roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(6), 613–673.

Bertaut, C. C. (1998). Stockholding behavior of U.S. households: evidence from the 1983-1989 survey of consumer finances. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(2), 263–275.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 26–60.

Bracke, P., Hilber, C.A., & Silva, O. (2014). Homeownership and entrepreneurship: the role of mortgage debt and commitment. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 5048.

Bruce, D. (2000). Effects of the United States tax system on transitions into self-employment. Labour Economics, 7(5), 545–574.

Bruce, D. (2002). Taxes and entrepreneurial endurance: evidence from the self-employed. National Tax Journal, 55(1), 5–24.

Brunnermeier, M. K., & Nagel, S. (2008). Do wealth fluctuations generate time-varying risk aversion? Micro-evidence on individuals’ asset allocation. American Economic Review, 98(3), 713–736.

Bucks, B. K., Kennickell, A. B., Mach, T. L., & Moore, K. B. (2009). Changes in U.S. family finances from 2004 to 2007: evidence from the survey of consumer finances. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 95, A1–A56.

Cagetti, M., & De Nardi, M. (2006). Entrepreneurship, frictions, and wealth. Journal of Political Economy, 114(5), 835–870.

Calvet, L. E., Campbell, J. Y., & Sodini, P. (2009). Fight or flight? Portfolio rebalancing by individual investors. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1), 301–348.

Campbell, J. Y., & Cocco, J. F. (2003). Household risk management and optimal mortgage choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1449–1494.

Carree, M., van Stel, A., Thurik, R., & Wennekers, S. (2002). Economic development and business ownership: An analysis using data of 23 OECD countries in the period 1976–1996. Small Business Economics, 19(3), 271–290.

Chetty, R., Sandor, L., & Szeidl, A. (2017). The effect of housing on portfolio choice. The Journal of Finance, 72(3), 1171–1212.

Civera, A., Meoli, M., & Vismara, S. (2017). Policies for the provision of finance to science-based entrepreneurship. Annals of Science and Technology Policy, 1(4), 317–469.

Cocco, J. F. (2005). Portfolio choice in the presence of housing. The Review of Financial Studies, 18(2), 535–567.

Colombo, M. G., Cumming, D. J., & Vismara, S. (2016). Governmental venture capital for innovative young firms. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(1), 10–24.

Croce, A., D’Adda, D., & Ughetto, E. (2015). Venture capital financing and the financial distress risk of portfolio firms: how independent and bank-affiliated investors differ. Small Business Economics, 44(1), 189–206.

Cullen, J. B., & Gordon, R. H. (2007). Taxes and entrepreneurial risk-taking: theory and evidence for the U.S. Journal of Public Economics, 91(7–8), 1479–1505.

Curtin, R. T., Juster, T., & Morgan, J. N. (1989). Survey estimates of wealth: an assessment of quality. In R. Lipsey & H. S. Tice (Eds.), The measurement of saving, investment, and wealth (pp. 473–552). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Davis, S., & Willen, P. (2000). Using financial assets to hedge labor income risks: estimating the benefits. Mimeo: University of Chicago.

Decker, R., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R., & Miranda, J. (2014). The role of entrepreneurship in U.S. job creation and economic dynamism. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 3–24.

Dunn, T., & Holtz-Eakin, D. (2000). Financial capital, human capital, and the transition to self-employment: Evidence from intergenerational links. Journal of Labor Economics, 18(2), 282–305.

Elsas, R., & Florysiak, D. (2015). Dynamic capital structure adjustment and the impact of fractional dependent variables. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 50(5), 1105–1133.

Evans, D. S., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 808–827.

Fairlie, R. W. (2013). Entrepreneurship, economic conditions, and the great recession. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 22(2), 207–231.

Fairlie, R. W., & Krashinsky, H. A. (2012). Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship revisited. The Review of Income and Wealth, 58(2), 279–306.

Fratantoni, M. C. (1998). Homeownership and investment in risky assets. Journal of Urban Economics, 44(1), 27–42.

Gentry, W. M., & Hubbard, R. G. (2004). Entrepreneurship and household saving. Advances in Economic Analysis & Policy, 4(1), Article 8.

Goldman, D., & Maestas, N. (2013). Medical expenditure risk and household portfolio choice. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 28(4), 527–550.

Guiso, L., Tullio, J., & Terlizzese, D. (1996). Income risk, borrowing constraints, and portfolio choice. American Economic Review, 86(1), 158–172.

Hall, R. E., & Woodward, S. E. (2010). The burden of the nondiversifiable risk of entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 100(3), 1163–1194.

Heaton, J., & Lucas, D. (2000a). Portfolio choice and asset prices: the importance of entrepreneurial risk. The Journal of Finance, 55(3), 1163–1198.

Heaton, J., & Lucas, D. (2000b). Portfolio choice in the presence of background risk. The Economic Journal, 110(460), 1–26.

Hernández-Cánovas, G., & Martínez-Solano, P. (2007). Effect of the number of banking relationships on credit availability: Evidence from panel data of spanish small firms. Small Business Economics, 28(1), 37–53.

Holtz-Eakin, D., Joulfaian, D., & Rosen, H. S. (1994a). Entrepreneurial decisions and liquidity constraints. RAND Journal of Economics, 25(2), 334–347.

Holtz-Eakin, D., Joulfaian, D., & Rosen, H. S. (1994b). Sticking it out: entrepreneurial survival and liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy, 102(1), 53–75.

Hout, M., & Rosen, H. (2000). Self-employment, family background, and race. Journal of Human Resources, 35(4), 670–692.

Hurst, E., & Lusardi, A. (2004). Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 319–347.

Iyer, R., & Schoar, A. (2010). Are there cultural determinants of entrepreneurship? In J. Lerner & A. Schoar (Eds.), International differences in entrepreneurship (pp. 209–240). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ji, T. (2004). Essays on consumer portfolio and credit risk. Doctoral Dissertation, The Ohio State University.

Jianakoplos, N. A., & Bernasek, A. (1998). Are women more risk averse? Economic Inquiry, 36(4), 620–630.

Kanbur, S. M. (1979). Impatience, information and risk taking in a general equilibrium model of occupational choice. The Review of Economic Studies, 46(4), 707–718.

Kennickell, A.B. (2017). Wealth measurement in the survey of consumer finances: methodology and directions for future research. Statistical Journal of the IAOS, 33(1), 23–29.

Kihlstrom, R. E., & Laffont, J. J. (1979). A general equilibrium entrepreneurial theory of firm formation based on risk aversion. Journal of Political Economy, 87(4), 719–748.

Kimball, M. S. (1990). Precautionary savings in the small and in the large. Econometrica, 58(1), 53–73.

Kimball, M. S. (1993). Standard risk aversion. Econometrica, 61(3), 589–611.

Lyons, A.C., & Yilmazer, T. (2005). Health and financial strain: evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Southern Economic Journal, 71(4), 873–890.

Mach, T. (2007). Survey of consumer finances: presentation (November 2, 2007). 2007 Kauffman Symposium on Entrepreneurship and Innovation Data. Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1027931.

Moffitt, R. (1993). Identification and estimation of dynamic models with a time series of repeated cross-sections. Journal of Econometrics, 59(1–2), 99–123.

Moore, K. (2004). The effects of the 1986 and 1993 tax reforms on self-employment. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2004–05.

Moskowitz, T., & Vissing-Jørgensen, A. (2002). The returns to entrepreneurial investment: a private equity premium puzzle? American Economic Review, 92(4), 745–778.

Murteira, J. M. R., & Ramalho, J. J. S. (2016). Regression analysis of multivariate fractional data. Econometric Reviews, 35(4), 515–552.

Pence, K. M. (2006). 401(k)s and household saving: new evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Contributions to Economic Analysis & Policy, 5(1), Article 20.

Pratt, J. W., & Zeckhauser, R. J. (1987). Proper risk aversion. Econometrica, 55(1), 143–154.

Pryor, J. H., & Reedy, E. J. (2009). Trends in business interest among U.S. college students: an exploration of data available from the Cooperative Institutional Research Program (November 1, 2009). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1971393.

Puri, M., & Robinson, D. T. (2013). The economic psychology of entrepreneurship and family business. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 22(2), 423–444.

Ramalho, E. A., & Ramalho, J. J. S. (2017). Moment-based estimation of nonlinear regression models with boundary outcomes and endogeneity, with applications to nonnegative and fractional responses. Econometric Reviews, 36(4), 397–420.

Ramalho, E. A., Ramalho, J. J. S., & Murteira, J. M. R. (2011). Alternative estimating and testing empirical strategies for fractional regression models. Journal of Economic Surveys, 25(1), 19–68.

Reynolds, P. D., & Curtin, R. T. (2008). Business creation in the United States: panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics II initial assessment. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 4(3), 155–307.

Risk Management for a Small Business Curriculum. Resource Document. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/files/INSTRUCTOR_GUIDE_RISK_MANAGEMENT.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2018.

Robb, A. M., & Robinson, D. T. (2014). The capital structure decisions of new firms. The Review of Financial Studies, 27(1), 153–179.

Roodman, D. (2011). Estimating fully observed recursive mixed-process models with cmp. The Stata Journal, 11(2), 159–206.

Rosen, H., & Willen, P. (2002). Risk, return and self-employment. University of Chicago/Princeton University Discussion Paper. Available at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.463.9726&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Rostamkalaei, A., & Freel, M. (2016). The cost of growth: small firms and the pricing of bank loans. Small Business Economics, 46(2), 255–272.

Sabelhaus, J., & Pence, K. (1999). Household saving in the ‘90s: evidence from cross-section wealth surveys. The Review of Income and Wealth, 45(4), 435–453.

Stangler, D. (2009). The coming entrepreneurship boom. SSRN Working Paper No. 1456428.

Sundén, A. E., & Surette, B. J. (1998). Gender differences in the allocation of assets in retirement savings plans. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 88(2), 207–211.

Verbeek, M., & Vella, F. (2005). Estimating dynamic models from repeated cross-sections. Journal of Econometrics, 127(1), 83–102.

Vereshchagina, G., & Hopenhayn, H. A. (2009). Risk taking by entrepreneurs. American Economic Review, 99(5), 1808–1830.

Wang, S. (2012). Credit constraints, job mobility and entrepreneurship: evidence from a property reform in China. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(2), 523–551.

Wong, P. K., Ho, Y. P., & Autio, E. (2005). Entrepreneurship, innovation and economic growth: evidence from GEM data. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 335–350.

Yao, R., & Zhang, H. (2005). Optimal consumption and portfolio choices with risky housing and borrowing constraints. The Review of Financial Studies, 18(1), 197–239.

Zissimopoulos, J., Karoly, L.A., & Gu, Q. (2009). Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and self-employment: the case of older workers. RAND Working Paper WR-725.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation for which the author is grateful. The author thanks seminar participants at the University of Indiana School of Public and Environmental Affairs for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was funded in part by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors. Any views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Census Bureau.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gurley-Calvez, T., Lugovskyy, J. The role of entrepreneurial risk in financial portfolio allocation. Small Bus Econ 53, 839–858 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0104-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0104-7