Abstract

This work explores the relationship between exports, global value chains (GVCs)’ participation and position, and firms’ productivity. To this aim, we combine the most recent World Bank Enterprise Survey in Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and World Trade Organization trade in value-added data. To explore the above relationship, we adopt an extended version of the standard Cobb-Douglas output function including indicators of export performance and GVCs. We control for heterogeneity among firms (by country, region, and industry), sample selection, firms’ characteristics, and reverse causality. Our empirical outcomes confirm the presence of a positive relationship between participation in international activities and firm performance. They also show that both participation in GVCs and position within GVCs matter. These findings have strong policy implications and may help policymakers in choosing the best policy options to enhance the link between GVCs’ integration and firms’ productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

De Loecker (2010) states that current methods used to test for learning by exporting are biased toward rejecting the hypothesis of positive effects of exports on productivity.

The value added reflects the value that is added by industries in producing goods and services. It is equivalent to the difference between the industry output and the sum of its intermediate inputs. Looking at trade from a value-added perspective better reveals how upstream domestic industries contribute to exports, as well as how much (and how) firms participate in GVCs (OECD–WTO, 2012).

Such as the World Input-Output Database (WIOD), the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP), and the EORA-MRIO database.

The TiVA version we use in this work provides 39 indicators for 57 countries (34 OECD countries plus 23 other economies, including Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, the Russian Federation, and South Africa) with a breakdown into 18 industries. Like for the WBES, the industry classification is based on the ISIC, Rev. 3.1.

We note a caveat in this decomposition at the industry level. While the value added embedded in a given imported intermediate could travel across many sectors before it is exported, the adopted decomposition traces only the direct and indirect effects.

Specifically, we match the TiVA GVC indicators computed for 2009 with the characteristics of firms available in the LAC WBES survey for 2010 that refer to the last completed fiscal year (2009).

The limitations of the WBES firm-level data have been acknowledged in the literature: for example, their being confined to the formal economy, their focus on manufacturing firms, and their variable levels of representativeness (Grazzi et al., 2016).

Only direct exporters with direct exports above 10% of annual total sales are considered exporters, whereas only firms with 10% of ownership held by private foreign investors are considered foreign owned.

Note that in this descriptive analysis, we use the firm-level data from the 2010 WBES survey for Argentina, Chile, and Mexico since the information collected in the surveys refers to characteristics of the firm to the last completed fiscal year (2009), and the 2009 WBES survey from Brazil.

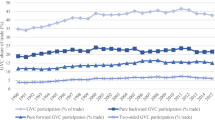

For the industrialized economies, we selected the USA, Japan, and Germany; for the emerging economies, we selected China, India, and South Korea; and for the developing/transitioning economies, we selected Poland, Turkey, and South Africa.

We use here labor productivity as a proxy of firm productivity. We acknowledge this is not the only (and probably also not the best) measure. Unfortunately, the available LAC WBES cross-sectional dataset is not suited to calculate other measures (e.g., total factor productivity) using the standard methodologies.

Although data by subnational regions are not representative of their relative economic relevance, subnational dummies are included in our analysis to capture additional unobserved heterogeneity across firms.

We eliminated the observations of the last 5 percentiles of our measure of labor productivity in order to clean it of potential outliers and keep consistency with the hypothesis of normal distribution. Without truncating, the outcomes do not change significantly. The results are available upon request.

Since we are fully aware of the selection mechanism, we easily identify selection in exporting by looking at the following exclusion restrictions: firms’ size and international linkages. This latter is proxied by the presence of foreign ownership (i.e., firm with at least 10% ownership held by private foreign investors). The selection equation estimates are then used to construct a proxy of the non-selection hazard, the so-called “inverse Mills ratio” (IMR) term, defined as \( {\lambda}_i=\frac{\phi \left[{x}_i^{\prime}\beta \right]}{\Phi \left[{x}_i^{\prime}\beta \right]} \) (Wooldridge, 2010). This term is then included in the main equation regression where only the truncated dependent variable is considered to derive the so-called “selection coefficient” (θ IMR). A simple t test of whether H 0: θ IMR = 0 is a workable test for sample selectivity bias. Note that because the IMR is a non-linear function of the variables included in the first-stage model, the second-stage equation is identified because of this non-linearity also when there is no “exclusion restriction” (i.e., Z = X).

Different from the IV technique, the CF approach controls for the likely endogeneity bias by directly adding the estimated residual of a first-stage equation (ρ) into the main regression. This residual is, by definition, uncorrelated with the endogenous variable and provides an unbiased CF estimator that is generally more precise than the IV estimator (Wooldridge, 2010).

As the main excluded instrument in our analysis, we use the following variable: “average time to clear imports from customs (in days).” With respect to other options, it is characterized by a sufficient number of observations and proves to be the most relevant instrument for the value of exports. It can be argued that better performing firms are more likely to better prepare trade documents and shipments and thereby spend less time in customs or in getting a license. However, in our case, the weak correlation between firm labor productivity and the above instrument confirms that these trade obstacles are more related to causes that are external to firms (e.g., procedures, institutional efficiency, etc.). Because of the sample selection, the IMR from the selection equation has been also added as the excluded instrument in the first-stage regression.

Due to space limitations, the first-stage estimates are not reported in the table but can be provided by the authors upon request.

Concerning the validity of the excluded instruments, Wooldridge’s score test for over-identifying restrictions (robust to heteroscedasticity) does not reject the null hypothesis that our instruments are valid at the 5% significance level and the Angrist-Pischke (AP) F statistics strongly rejects the null of weak instruments. Furthermore, the Stock and Yogo minimum eigenvalue statistic is high, and Shea’s adjusted partial R 2 statistic shows that our instruments add enough information in the first-stage equation.

Please acknowledge that the residuals in the main equation ρ actually depend on the sampling error in the first-stage equation unless ρ is equal to zero.

The Levine test is similar to the standard ANOVA test but less sensitive to the violation of normality assumption. The conventional Levine test strongly rejects the null hypothesis both when centered at the mean (with Pr > F = 0.004) and when centered at the median (with Pr > F = 0.009).

References

Agostino, M., Giunta, A., Nugent, J. B., Scalera, D., & Trivieri, F. (2015). The importance of being a capable supplier: Italian industrial firms in global value chains. International Small Business Journal, 33(7), 708–730. doi:10.1177/0266242613518358.

Alcacer, J., & Oxley, J. (2014). Learning by supplying. Strategic Management Journal, 35(2), 204–223. doi:10.1002/smj.213.

Alvarez, R., & López, R. (2005). Exporting and performance: evidence from Chilean plants. Canadian Journal of Economics, 38(4), 1384–1400. doi:10.1111/j.0008-4085.2005.00329.x.

Antràs, P., Chor, D., Fally, T., & Hillberry, R. (2012). Measuring the upstreamness of production and trade flows. American Economic Review, 102(3), 412–416. doi:10.1257/aer.102.3.412.

Bair, J. (2005). Global capitalism and commodity chains: looking back, going forward. Competition & Change, 9(2), 153–180. doi:10.1179/102452905X45382.

Baldwin, R. (2013), Global supply chains: why they emerged, why they matter, and where they are going. In D. K. Elms and P. Low (eds), Global value chains in a changing world, WTO.

Baldwin, R., & Lopez-Gonzalez, J. (2015). Supply-chain trade: a portrait of global patterns and several testable hypotheses. The World Economy, 38(11), 1682–1721. doi:10.1111/twec.12189.

Baldwin, R., & Venables, A. (2013). Spiders and snakes: offshoring and agglomeration in the global economy. Journal of International Economics, 90(2), 245–254. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2013.02.005.

Baldwin, R.. 2014. Trade and industrialization after globalization’s second unbundling: how building and joining a supply chain are different and why it matters. In Feenstra R.C and A. M. Taylor (editors) Globalization in an age of crisis: multilateral economic cooperation in the twenty-first century, University of Chicago Press, ISBN: 9780226030753.

Balié, J., D. Del Prete, E. Magrini, P. Montalbano & S. Nenci. 2017. Agriculture and food global value chains in Sub-Saharan Africa: does bilateral trade policy impact on backward and forward participation? Working Papers Series Sapienza-DiSSE, No. 4/2017. www.diss.uniroma1.it/sites/.../DiSSE_Balieetal_wp4_2017.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2017.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (1995). Exporters, jobs, and wages in U.S. manufacturing: 1976–1987. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Microeconomics, 67–119. doi:10.2307/2534772.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (1999). Exceptional exporter performance: cause, effect, or both? Journal of International Economics, 47, 1–25. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(98)00027-0.

Bernard, A., Eaton, J., Jensen, B., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290. doi:10.1257/000282803769206296.

Blyde, J.S. (Ed.) 2014. Synchronized factories. Latin America and the Caribbean in the era of global value chains, Springer, ISBN 978-3-319-09991-0.

Cattaneo, O., Gereffi, G., Miroudot, S., & Taglioni, D. (2013). Joining, upgrading and being competitive in global value chains: a strategic framework. Policy research Working paper 6406. Washington, DC, The World Bank: Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2248476.

Clerides, S. K., Lach, S., & Tybout, J. (1998). Is learning by exporting important? Micro-dynamic evidence from Colombia, Mexico, and Morocco. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 903–947. doi:10.1162/003355398555784.

Contreras, O. F., Carrillo, J., & Alonso, J. (2012). Local entrepreneurship within global value chains: a case study in the Mexican automotive industry. World Development, 40(5), 1013–1023. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.11.012.

Corredoira, R. A., & McDermott, G. A. (2014). Adaptation, bridging and firm upgrading: How non-market institutions and MNCs facilitate knowledge recombination in emerging markets. Journal of International Business Studies, 45, 699–722. doi:10.1057/jibs.2014.19.

Costinot, A., Vogel, J., & Wang, S. (2013). An elementary theory of global supply chains. Review of Economic Studies, 80(1), 109–144. doi:10.1093/restud/rds023.

Crespi, G., Fernández-Arias, E., & Stein, E. (Eds.). (2014). Rethinking productive development: sound policies and institutions for economic transformation. Washington, DC: Palgrave Macmillan for Inter-American Development Bank ISBN 978-1-137-39399-9.

De Backer, K. & Miroudot, S. 2014. Mapping global value chains. ECB Working Paper No. 1677. Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=2436411. Accessed 4 July 2014.

De La Cruz, J., Koopman, R., & Wang, Z. (2011). Estimating foreign value-added in Mexico’s manufacturing exports. Working paper no. 2011-04. Washington, DC: U.S. International Trade Commission https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/EC201104A.pdf.

De Loecker, J. (2007). Do exports generate higher productivity? Evidence from Slovenia. Journal of International Economics, 73(1), 69–98. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.03.003.

De Loecker, J. (2010). A note on detecting learning by exporting. In NBER working paper 16548. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w16548.

Dussel Peters, E. (2003). Ser maquila o no ser maquila, ¿es ésa la pregunta? Comercio Exterior, 53(4), 328–336 http://revistas.bancomext.gob.mx/rce/magazines/19/4/RCE.pdf.

Eliasson, K., Hansson, P., & Lindvert, M. (2012). Do firms learn by exporting or learn to export? Evidence from small and medium-sized enterprises. Small Business Economics, 39, 453–472. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9314-3.

Fafchamps, M., El Hamine, S., & Zeufack, A. (2008). Learning to export: evidence from Moroccan manufacturing. Journal of African Economies, 17(2), 305–355. doi:10.1093/jae/ejm008.

Fally, T. (2012). Production staging: measurement and facts. Boulder: University of Colorado http://are.berkeley.edu/~fally/Papers/Fragmentation_US_Aug_2012.pdf.

Farole, T., & Winkler, D. (Eds.). (2014). Making foreign direct investment work for Sub-Saharan Africa: local spillovers and competitiveness in global value chains. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Fernandez, A., & Isgut, A. (2005). Learning-by-doing, learning-by-exporting, and productivity: evidence from Colombia. Policy research working paper 3544. Washington, DC: The World Bank Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=695444.

Fernández-Arias, E. (2014). Productivity and factor accumulation in Latin America and the Caribbean: a database. Washington, DC: Departamento de Investigación, Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo Available in: http://www. iadb.org/research/pub_desc.cfm?pub_id=DBA-015.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., Kaplinsky, R., & Sturgeon, T. J. (2001). Introduction: globalisation, value chains and development. IDS Bulletin, 32(3), 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2001.mp32003001.x.

Gereffi, G. (1994). The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains: how US retailers shape overseas production networks. In G. Gereffi & M. Korzeniewicz (Eds.), Commodity chains and global capitalism (pp. 95–122). Westport: Praeger ISBN 0-275-94573-1.

Gereffi, G. (1999). International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. Journal of International Economics, 48, 37–70. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(98)00075-0.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. doi:10.1080/09692290500049805.

Giovannetti, G., Marvasi, E., & Sanfilippo, M. (2015). Supply chains and the internationalization of small firms. Small Business Economics, 44(4), 845–865. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9625-x.

Girma, S., Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2004). Does exporting increase productivity? A microeconometric analysis of matched firms. Review of International Economics, 12(5), 855–866. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2004.00486.x.

Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2005). Upgrading in global value chains: lessons from Latin American clusters. World Development, 33(4), 549–573. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.01.002.

Grazzi, M., Pietrobelli, C., & Szirmai, A. (2016). Determinants of enterprise performance in Latin America and the Caribbean: what does the micro-evidence tell us? In M. Grazzi & C. Pietrobelli (Eds.), Firm innovation and productivity in Latin America and the Caribbean (pp. 1–36). US: Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-58151-1.

Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2007). Firm heterogeneity, exporting and foreign direct investment. Economic Journal, 117(517), 134–161. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02018.x.

Greenville, J., Beaujeu, R., & Kawasaki, K. (2016). GVC participation in the agriculture and food sectors. Joint working party on agriculture and trade. OECD Trade and Agriculture Directorate; TAD/TC/CA/WP(2016)1.

Grossman, G. M., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2008). Trading tasks: a simple theory of offshoring. The American Economic Review, 98(5), 1978–1997. doi:10.1257/aer.98.5.1978.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the world economy. Cambridge: MIT ISBN: 9780262071369.

Hayakawa, K., Machikita, T., & Kimura, F. (2012). Globalization and productivity: a survey of firm-level analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(2), 332–350. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6419.2010.00653.x.

Herrigel, G., Wittke, V., & Voskamp, U. (2013). The process of Chinese manufacturing upgrading: transitioning from unilateral to recursive mutual learning relations. Global Strategy Journal, 3(1), 109–125. doi:10.1111/j.2042-5805.2012.01046.x.

Hummels, D., Ishii, J., & Yi, K. (2001). The nature and growth of vertical specialization in world trade. Journal of International Economics, 54(1), 75–96. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(00)00093-3.

Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2002). How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Regional Studies, 36(9), 1017–1027. doi:10.1080/0034340022000022198.

IMF (2015). Regional economic outlook. Sub-Saharan Africa, ISBN-13: 978-1-49832-984-2.

Johnson, R. C., & Noguera, G. (2012a). Accounting for intermediates: production sharing and trade in value added. Journal of International Economics, 86, 224–236. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.10.003.

Johnson, R. C., & Noguera, G. (2012b). Fragmentation and trade in value added over four decades. In NBER Working paper 18186. Cambridge: MA. doi:10.3386/w18186.

Koopman, R., Wang, Z., & Wei, S. J. (2014). Tracing value-added and double counting in gross exports. American Economic Review, 104(2), 459–494. doi:10.1257/aer.104.2.459.

Koopman, R., Wang, Z., & Wei, S.-J. (2011). Give credit where credit is due: tracing value added in global production chains. In NBER working paper 16426. Cambridge: MA. doi:10.3386/w16426.

Kowalski, P., Gonzalez, J. L., Ragoussis, A., & Ugarte, C. (2015). Participation of developing countries in global value chains: implications for trade and trade-related policies. OECD trade policy papers, no. 179. Paris: OECD. doi:10.1787/5js33lfw0xxn-en.

Lileeva, A., & Trefler, D. (2010). Improved access to foreign markets raises plant-level productivity…for some plants. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3), 1051–1099. doi:10.1162/qjec.2010.125.3.1051.

López, R. (2005). Trade and growth: reconciling the macroeconomic and microeconomic evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys, 19(4), 623–648. doi:10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00264.x.

MacDuffie, J. P., & Helper, S. (2006). Collaboration in supply chains: with and without trust. In I. C. Heckscher & P. S. Adler (Eds.), The firm as a collaborative community: reconstructing trust in the knowledge economy (pp. 417–466). Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN13: 9780199286034.

Martins, P. S., & Yang, Y. (2009). The impact of exporting on firm productivity: a meta-analysis of the learning-by-exporting hypothesis. Review of World Economics, 145, 431–445. doi:10.1007/s10290-009-0021-6.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725. doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00467.

Meyer, K., & Sinani, E. (2009). When and where does foreign direct investment generate positive spillovers? A meta-analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(7), 1075–1094. doi:10.1057/jibs.2008.111.

Miroudot, S., & Ragousssis, A. 2009. Vertical trade, trade costs and FDI. Trade policy working paper 89. Paris: OECD. DOI:10.1787/222111384154.

OECD–WTO. (2012). Trade in value-added: concepts, methodologies, and challenges. Joint OECD–WTO note. Washington, DC: OECD–WTO http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/49894138.pdf.

Pagés, C. (Ed.). (2010). The age of productivity: transforming economies from the bottom up. Washington, DC: Palgrave Macmillan for Inter-American Development Bank ISBN 978-0-230-10761-8.

Park, A., Yang, D., Shi, X., & Jiang, Y. (2010). Exporting and firm performance: Chinese exporters and the Asian financial crisis. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 822–842. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00033.

Pietrobelli, C. & Staritz, C. (2017). Cadenas Globales de Valor y Políticas de Desarrollo. Desarrollo Económico, vol. 56, N° 220 (enero-abril).

Pietrobelli, C. & Staritz, C. (2013). Challenges for global value chain interventions in Latin America. Technical Note No. IDB-TN-548, May. Inter-American Bank. http://www.iadb.org/projectDocument.cfm?id=38815216. Accessed 1 August 2013.

Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2007). Upgrading to compete. In Global value chains, SMEs and clusters in Latin America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press ISBN 9781597820325.

Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2011). Global value chains meet innovation systems: are there learning opportunities for developing countries? World Development, 39(7), 1261–1269. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.05.013.

Porter, M. (1985). Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: Free ISBN: 978-0684841465.

Sako, M. (2004). Supplier development at Honda, Nissan and Toyota: comparative case studies of organizational capability enhancement. Industrial and Corporate Change, 13(2), 281–308. doi:10.1093/icc/dth012.

Serti, F., & Tomasi, C. (2008). Self-selection and post-entry effects of exports: evidence from Italian manufacturing firms. Review of World Economics, 144(4), 660–694. doi:10.1007/s10290-008-0165-9.

Singh, T. (2010). Does international trade cause economic growth? A survey. The World Economy, 33(11), 1517–1564. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01243.x.

Stehrer, R. 2013. Accounting relations in bilateral value added trade. Working Paper. Vienna: the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW), https://wiiw.ac.at/accounting-relations-in-bilateral-value-added-trade-dlp-3021.pdf.

Taglioni, D. & Winkler, D. (2016). Making global value chains work for development. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

Theyel, N. (2013). Extending open innovation throughout the value chain by small and medium-sized manufacturers. International Small Business Journal, 31(3), 256–274. doi:10.1177/0266242612458517.

Unctad, G. (2013). Global value chains: investment and trade for development. World investment report. New York and Geneva: United Nations Press.

Van Biesebroeck, J. (2005). Exporting raises productivity in Sub-Saharan African manufacturing plants. Journal of International Economics, 67(2), 373–391. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2004.12.002.

Verhoogen, E. A. (2008). Trade, quality upgrading, and wage inequality in the Mexican manufacturing sector. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 489–530. doi:10.1162/qjec.2008.123.2.489.

Wagner, J. (2007). Exports and productivity: a survey of the evidence from firm-level data. The World Economy, 30(1), 60–82. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00872.x.

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: a survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World Economics, 148(2), 235–267. doi:10.1007/s10290-011-0116-8.

Wang, Z., Wei, S.-J., & Zhu, K. (2013). Quantifying international production sharing at the bilateral and sector levels. NBER working paper 19677. doi:10.3386/w19677.

Woldesenbet, K., Ram, M., & Jones, T. (2012). Supplying large firms: the role of entrepreneurial and dynamic capabilities in small businesses. International Small Business Journal, 30(5), 493–512. doi:10.1177/0266242611396390.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT ISBN: 9780262232586.

Wynarczyk, P., & Watson, R. (2005). Firm growth and supply chain partnerships: an empirical analysis of UK SME subcontractors. Small Business Economics, 24, 39–51. doi:10.1007/s11187-005-3095-0.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Juan Blyde, Anna Giunta, Matteo Grazzi, Christian Volpe Martincus, Siobhan Pangerl, and Adam Szirmai for their insightful comments and suggestions. They also thank the seminar participants at the Centro Rossi-Doria Workshop “Global Value Chains for Food and Nutrition Security,” University of Roma Tre, the ETSG International Conference, Munich University, and the IDB Workshop “Determinants of Firm Performance in LAC: What Does the Micro Evidence Tell Us?,” Washington, DC. Finally, they are indebted to both the Editor and the two anonymous referees for their useful comments and suggestions for improvement. This publication was made possible thanks to the support of the Inter-American Development Bank. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Inter-American Development Bank, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

According to the methodology proposed by Koopman et al. (2011), gross exports can be decomposed into the following value-added components (see Fig. 4):

-

Direct domestic value added embodied in exports of goods and services (DVA), which reflects the direct contribution made by an industry in producing a final or intermediate good or service for export (i.e., value added exported in final goods or in intermediates absorbed by direct importers).

-

Indirect domestic value added embodied in intermediate exports (IVA), which reflects the indirect contribution of domestic supplier industries of intermediate goods or services used in the exports of other countries (i.e., value added exported in intermediates re-exported to third countries).

-

Re-imported domestic value added embodied in gross exports (RVA), which reflects the domestic value added that was exported in goods and services used to produce the intermediate imports of goods and services used by the industry (i.e., exported intermediates that return home).

-

Foreign value-added embodied in gross exports (FVA), which reflects the foreign value-added content of intermediate imports embodied in the final and intermediate gross exports (i.e., other countries domestic value added in intermediates used in exports).

These terms are complemented by a further component that quantifies the so-called “double counting,” i.e., the value of intermediate goods that cross international borders more than once (Koopman et al., 2014). The pure double-counted (DC) component reflects the (double-counted) values in intermediate goods trade that are originated at home and abroad.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montalbano, P., Nenci, S. & Pietrobelli, C. Opening and linking up: firms, GVCs, and productivity in Latin America. Small Bus Econ 50, 917–935 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9902-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9902-6