Abstract

In this paper, we unveil a disregarded benefit of product market competition for firms. We introduce the probability of bankruptcy in a simple model where firms compete à la Cournot and apply for collateralized bank loans to undertake productive investments. We show that the number of competitors and the existence of outsiders willing to acquire the productive assets of distressed incumbents affect the equilibrium share of investment financed by bank credit. Using a sample of Italian manufacturing firms, mostly small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), we found evidence showing that the degree of product market competition is positively correlated with the share of investment financed by bank credit only when outsiders are absent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our setup is characterized by symmetric information and firms’ limited liability: assuming bank risk-aversion would not change the main results because the optimal risk-sharing agreement would be unaffected.

One can easily check that the results of this section are not affected when, consistently with our analysis, outsiders are assumed to be endowed with limited funding M and to borrow the residual amount from a risk-neutral bank subject to a break-even constraint.

Following a proof similar to that in the Appendix A.3, one can prove that the equilibrium capacity is still \(\hat {q}\left (\cdot \right ) \) when firms are self-financed and there are at least two outsiders.

The model focuses on the simplest product market structures, N=2 vs. N=3. A preliminary analysis of the general case with N≥2 initial firms is provided by Cerasi et al. (2013).

All the companies with more than 500 workers are included in the sample, while smaller firms are drawn at random according to a stratified sampling scheme, with (80) strata defined on the basis of 5 size classes of employment, 4 territorial areas and 4 Pavitt sectors (see UniCredit Corporate Banking 2008). The companies are contacted and interviewed by phone (CATI mode) or can self-complete the questionnaire and hand in by email or fax.

Accornero et al. (2015) estimate that “the number of non-financial firms accessing the market from 2002 to 2013 was, on average, about 160 per year”.

Firms’ total leverage would not be as useful for our empirical analysis. The total stock of debt, cumulated over the past years and issued for many different reasons by the company, can hardly be associated to a specific investment. As a matter of fact, the association between the specific investment and the way it has been financed is crucial for our purpose: purchases of equipment and machinery might reveal that those purchased assets will be used as collateral in the credit contract.

For investment in land and real estate, redeployment costs are relatively low and it can be easily argued that in case of project failure these assets are attractive for all firms, regardless of their product specialization. In terms of our model, it is as if there are always outsiders willing to purchase land and real estate assets.

Due to data limitation, we could not retrieve the information on employees from AIDA and we had to rely on the number of employees in 2004 as self-reported in the survey.

This information is borrowed from Cerasi et al. (2009), where the market shares are computed using the number of branches of individual banks in each local market.

The fall in the number of companies is due to survey item nonresponse, not to the lack of balance sheet data; the latter are missing for only three companies.

References

Accornero, M., Finaldi Russo, P., Guazzarotti, G., & Nigro, V. (2015). First-time corporate bond issuers in Italy. Bank of Italy Occasional Paper No. 269. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2609309.

Acharya, V., Bharath, S., & Srinivasan, A. (2007). Does industry-wide distress affect defaulted firms? Evidence from creditor recoveries. Journal of Financial Economics, 85(3), 787–821. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.05.011.

Albareto, G., Benvenuti, M., Mocetti, S., Pagnini M., & Rossi, P. (2011). The organization of lending and the use of credit scoring techniques in italian banks. Journal of Financial Transformation, 32, 143–157. http://www.capco.com/insights/capco-institute/the-organization-of-lending-and-the-use-of-credit-scoring-techniques-in-italian-banks.

Almeida, H., Campello, M., & Hackbarth, D. (2011). Liquidity mergers. Journal of Financial Economics, 102(3), 526–558. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.08.002.

Altman, E. (2000). Predicting financial distress of companies: Revisiting the Z-Score and zeta models. Stern School of Business working paper. New York University. http://www.altmanzscoreplus.com/sites/default/files/papers/PredFnclDistr.pdf.

Antonielli, M., & Mariniello, M. (2014). Antitrust risk in EU manifacturing: A sector-level ranking. Bruegel WP 2014/07 http://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/publications/WP_2014_07_01.pdf.

Beck, T., & Demirguc-Kunt, A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(11), 2931–2943. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.009.

Benmelech, E., & Bergman, N.K. (2009). Collateral pricing. Journal of Financial Economics, 91 (3), 339–360. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.03.003.

Benmelech, E., & Bergman, N.K. (2011). Bankruptcy and the collateral channel. Journal of Finance, 66(2), 337–378. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01636.x.

Benmelech, E., Garmaise, M., & Moskowitz, T. (2005). Do liquidation values affect financial contracts? Evidence from commercial loan contracts and zoning regulation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 1121–1154. doi:10.1093/qje/120.3.1121.

Berger, A., & Udell, G. (1995). Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance. The Journal of Business, 68(3), 351–381. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2353332.

Bertand, M., & Kramarz, F. (2002). Does entry regulation hinder job creation? Evidence from the frenc retail industry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1369–1413. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4132481.

Bonaccorsi di Patti, E. (2006). La diffusione delle garanzie reali e personali nel credito alle imprese. Unpublished working paper. Bank of Italy.

Brander, J., & Lewis, T. (1986). Oligopoly and financial structure: The limited liability effect. American Economic Review, 76(5), 956–970. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1816462.

Branstetter, L., Lima, F., Taylor, L. J., & Venancio, A. (2014). Do entry regulations deter entrepreneurship and job creation? Evidence from recent reforms in portugal. The Economic Journal, 124, 805–832. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12044.

Calcagnini, G., Farabullini, F., & Giombini, G. (2014). The impact of guarantees on bank loan interest rates. Applied Financial Economics, 24(4-6), 397–412. doi:10.1080/09603107.2014.881967.

Cerasi, V., Chizzolini, B., & Ivaldi, M. (2009). The impact of mergers on the degree of competition in the banking industry. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 7618. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1522006.

Cerasi, V., & Fedele, A. (2011). Does product market competition increase credit availability? The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 11(1). doi:10.2202/1935-1682.2916. (Topics), Article 41.

Cerasi, V., Fedele, A., & Miniaci, R. (2013). Product market competition and collateralized debt (February 15, 2013) Available at SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2097884.

Cestone, G. (1999). Corporate financing and product market competition: An overview. Giornale degli Economisti e Annali di Economia, 58, 269–300. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23248263.

Chaney, T., Sraer, D., & Thesmar, D. (2012). The collateral channel: How real estate shocks affect corporate investment. American Economic Review, 102(6), 2381–2409. doi:10.1257/aer.102.6.2381.

Duan, N., Manning, W.G., Morris, C.N., & Newhouse, J.P. (1983). A comparison of alternative models for the demand for medical care. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 1(2), 115–126. doi:10.2307/1391852.

European Commission (2014). Annual report on european smes 2013/2014. A partial and fragile recovery. http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/16121/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

Frèsard, L., & Valta, P. (2015). How does corporate investment respond to increased entry threat?. Review of Corporate Finance Studies, cfv015. doi:10.1093/rcfs/cfv015.

Gan, J. (2007). Collateral debt capacity and corporate investment: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Financial Economics, 85(3), 709–734. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.06.007.

Gavazza, A. (2010). Asset liquidity and financial contracts: Evidence from aircraft leases. Journal of Financial Economics, 95(1), 62–84. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2009.01.004.

Giovannini, A., Mayer, C., Micossi, S., Di Noia, C., Onado, M., Pagano, M., & Polo, A. (2015). Restarting european long-term investment finance. A green paper discussion document, CEPR Press. http://reltif.cepr.org/sites/default/files/RELTIF_Green%20Paper.pdf.

Habib, M., & Johnsen, B. (1999). The financing and redeployment of specific assets. Journal of Finance, 54(2), 693–720. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00122.

Heckman, J.J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1912352.

Holmstrom, B., & Tirole, J. (1997). Financial intermediation, loanable funds and the real sector. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(3), 663–691. doi:10.1162/003355397555316.

Huang, H.H., & Lee, H.H. (2013). Product market competition and credit risk. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(2), 324–340. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2012.09.001.

Norden, L., & van Kempen, S. (2013). Corporate leverage and the collateral channel. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(12), 5062–5072. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.09.001.

Ortiz-Molina, H., & Phillips, G.M. (2014). Real Asset Illiquidity and the Cost of Capital. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 49(1), 1–32. doi:10.1017/S0022109014000210.

Rajan, R. (1992). Insiders and outsiders. The choice between informed and arm’s-lenght debt. Journal of Finance, 48(4), 1367–1400. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb04662.x.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 559–586. http://www.jstor.org/stable/116849.

Rauh, J., & Sufi, A. (2012). Explaining corporate capital structure: Product markets, leases, and asset similarity. Review of Finance, 16(1), 115–155. doi:10.1093/rof/rfr023.

Rostam-Afschar, D. (2014). Entry regulation and entrepreneurship: a natural experiment in German craftsmanship. Empirical Economics, 47, 1067–1101. doi:10.1007/s00181-013-0773-7.

Schmalensee, R. (1977). Using the h-index of concentration with published data. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 59(2), 186–193. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1928815.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1992). Liquidation values and debt capacity: a market equilibrium approach. Journal of Finance, 47(4), 1343–1366. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb04661.x.

UniCredit Corporate Banking (2008). Decima indagine sulle imprese manifatturiere italiane. Rapporto Corporate, 1, 2008.

Valta, P. (2012). Competition and the cost of debt. Journal of Financial Economics, 105(3), 661–682. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.04.004.

Xu, J. (2012). Profitability and capital structure: Evidence from import penetration. Journal of Financial Economics, 106(2), 427–446. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.05.015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A: Proofs

1.1 A.1 Triopoly

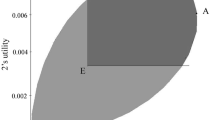

To simplify the notation, we anticipate that \(q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \) is the equilibrium capacity set by each rival at date 0. The representative firm A’s expected profit function at date 0, U A , is thus given by

When firm A is healthy—with probability p —at date 1 it repays r A to bank A, produces at the maximum capacity q A without additional production costs and it earns P 3 q A , where \(P_{3}=1-\left [ q_{A}+2q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \right ] \) indicates the price of the homogeneous good when the total production is equal to the total capacity, \(q_{A}+2q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \), regardless of the allocation of PAs among healthy firms. Moreover, when one rival, either firm 2 or firm 3, fails—this occurs with probability \(2p\left (1-p\right ) \) —both firm A and the healthy rival are willing to purchase the failing firm’s PAs; firm A acquires these PAs with probability \(\frac {1}{2}\) and gets the extra-revenue \(P_{3}q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \). When both rivals fail—this occurs with probability (1−p)2 —firm A is the only potential buyer of the two rivals’ PAs and acquires them with probability 1; its extra-revenue is \(P_{3}2q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \). By contrast, if firm A fails—with probability (1−p) —it earns nothing. Finally, M denotes the opportunity cost of firm A’s own funds.

The expected profit function of bank A, V A , is given by

When firm A is successful—this occurs with probability p —bank A receives r A . Moreover, when only one rival fails—with probability \(2p\left (1-p\right ) \) —bank A lends an expected extra amount \(\frac {1}{2}P_{3}q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \) to firm A, which offers \(P_{3} q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \) to buy the PAs of the failing rival, \(\frac {1}{2}\) being the probability that firm A obtains the PAs on sale and actually pays the offered price. With probability \(\left (1-p\right )^{2}\), bank A funds the amount 2ε offered by firm A to acquire the PAs of both failing rivals. By contrast, firm A fails with probability 1−p. When both rivals are healthy—with probability p 2 —bank A sells firm A’s PAs at price P 3 q A ; with probability \(2p\left (1-p\right ) \) only one rival, either 2 or 3, is healthy and buys at price ε. Finally, the last term, c q A −M, is the opportunity cost of the amount lent to firm A, since we assume zero risk-free interest rate. Note that the expected cost of the extra credit in the event that firm A is the only healthy one, −p(1−p)22ε, cancels with the expected value recovered from the sale of firm A’s PAs in case only one rival is healthy, \(2\left (1-p\right )^{2}p\varepsilon \).

To obtain the firm A’s expected profits at date 0, we first calculate the expected repayment p r A required by bank A to break even:

The above value is positively affected by the opportunity cost of lending, \(\left (cq_{A}-M\right ) \), and by the expected extra-credit to firm A when the firm competes with an healthy rival to buy the failing firm’s PAs, \(2p^{2}\left (1-p\right ) \frac {1}{2}P_{3}q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \). On the contrary, p r A is negatively affected by the expected value recovered by bank A from the sale of firm A’s PAs when the two rivals are healthy, \(\left (1-p\right ) p^{2}P_{3}q_{A}\). Plugging Eq. 13 into Eq. 12 gives Eq. 4 where \(q_{B}+q_{C}=2q^{\ast }\left (3\right ) \).

1.2 A.2 Entry by outsiders

Duopoly Firm A’s expected profit function at date 0 is given by (1). Bank A’s expected profit function is instead affected by the new expected liquidation value of PAs and given by

The bank’s break-even condition is

Plugging this value into Eq. 1 yields Eq. 5.

Triopoly A similar reasoning can be invoked to compute Eq. 6 under triopoly.

1.3 A.3 Self-financed firms

To compute the representative self-financed firm A’s expected profit, we rely on the following reasoning. With probability p firm A actually competes in the product market by gaining P 2 q A . Moreover, when firm A is the only buyer because firm B is failing—probability \(p\left (1-p\right ) \) —firm A’s extra-profit is \(p\left (1-p\right ) \left [ P_{2}q_{B}-\varepsilon \right ] \), where P 2 q B is the extra-revenue thanks the additional capacity q B and ε is the offer to acquire the rival’s PAs. With probability \(\left (1-p\right ) \) firm A is in distress, in which case it cashes the expected liquidation value of its PAs, \(\left (1-p\right ) p\varepsilon \). Finally, firm A incurs the cost c q A of installing the capacity q A . Overall, the expected profit of firm A in case it is self-financed amounts to

Note the the above expression is equivalent to Eq. 4 after rearrangement. The result follows.

Appendix B: Additional table

In Table 3 we report the estimates of the parameters of Eqs. 7–9.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cerasi, V., Fedele, A. & Miniaci, R. Product market competition and access to credit. Small Bus Econ 49, 295–318 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9838-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9838-x

Keywords

- Product market competition

- Collateralised bank loans

- Resale of productive assets

- Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)