Abstract

To improve our understanding of the role that universities play in facilitating the transmission of knowledge to private-sector business enterprises so as to generate economic growth, this article builds on the Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship to develop a formal model of university-with-business enterprise collaborative research partnerships in which the outcome is both mutually desirable and feasible. This model shows that if a university seeks to act as a complement to private-sector collaborative R&D so that it will be attractive to both incumbent firms and startup entrepreneurs, it needs to structure its program so that business enterprise revenues increase and business enterprise R&D costs rise by a smaller proportion than revenues increase, if they rise at all (and a fall would be better). Such a structure is consistent with both business enterprise and university interests, but is only likely to be feasible if the university is subsidized to cover the cost of such public-private collaborative research partnerships. In the absence of such support, the university will have to cover its costs through a fee charged to participating business enterprises and that will result in the university being seen as a substitute rather than a complement to private-sector collaborative R&D, and thus the university will be seen as an unattractive partner for many business enterprises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Thus, the debate over whether entrepreneurship is essentially a process of creation or discovery (Alvarez and Barney 2007) misses the point. As Michelacci (2003) and Acs et al. (2009) argue, creation of knowledge by researchers and existing firms and the discovery of such knowledge by entrepreneurs are both required.

We abstract from the important impact that universities have through their role in educating and graduating students.

Åstebro and Bazzazian (2011), in their wide-ranging review of the empirical literature on the impact of universities on local entrepreneurship and economic development, rightly sound a cautionary note on our ability to make definitive claims about the causal impact of universities on economic development.

See Link and Scott (2005).

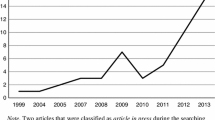

The Council on Competitiveness (1996, pp. 3–4) recently noted and emphasized this trend in the USA: “[P]articipants in the U.S. R&D enterprise will have to continue experimenting with different types of partnerships to respond to the economic constraints, competitive pressures and technological demands that are forcing adjustments across the board.…[and in response] industry is increasingly relying on partnerships with universities ….” Relatedly, Link (1996) showed that university participation in formal research joint ventures (RJVs) has increased steadily since the mid-1980s, Cohen et al. (1997) documented that the number of industry/university R&D centers increased by more than 60 % during the 1980s, and a recent survey of US science faculty by Morgan (1998) revealed that many desire even more partnership relationships with industry. Mowery and Teece (1996, p. 111) contend that such growth in strategic alliances in R&D is indicative of a “broad restructuring of the U.S. national R&D system.”

Cohen et al. (1997) provide a selective review of this literature, emphasizing the studies that have documented that university research enhances firms’ sales, R&D productivity, and patenting activity. See Blumenthal et al. (1986), Jaffe (1989), Adams (1990), Berman (1990), Feller (1990), Mansfield (1991, 1992), Van de Ven (1993), Bonaccorsi and Piccaluga (1994), Klevorick et al. Winter (1995), Zucker et al. (1994), Henderson et al. (1995), Mansfield and Lee (1996), Zeckhauser (1996), Campbell (1997), Baldwin and Link (1998), Lee (2000) and Lööf and Broström (2008). Cockburn and Henderson (1997) show that it was important for innovative pharmaceutical firms to maintain ties to universities. Hall et al. (2000, 2003) suggest that perhaps such research ties with universities increase the “absorptive capacity,” in the sense of Cohen and Levinthal (1989, 1990), of the innovative firms. This literature is reviewed by Audretsch et al. (2012).

GUIRR (2006, p. 8) point out that “Institutional practices and national resources should focus on fostering appropriate long-term partnerships between universities and industry.” While we do not offer recommendations about such partnerships in this article, we do acknowledge the importance of the timing of such relationships and their longevity. However, our model (below) is static and does not taking timing into account. Clearly, that is an area for future research.

Leyden and Link (2013) discuss collective entrepreneurship in the context of the management of places. Therein they hypothesize that the strategic management of places is functionally related to the collective positive entrepreneurial effort of individuals, each exercising his/her perception and action at different time based on their personal preferences, expertise, and estimation of the best steps forward. Collectively, they engage in what might be called a process of social sequential learning that moves a place forward for the common weal.

We thank an anonymous referee for pointing out that in a knowledge spillover perspective costs and profits are certainly important, as are other intermediary inputs and long-term strategies (for example, those that affect regional R&D culture and economic knowledge) that may or may not be captured in a static model that focused on costs and profits. We fully agree with this point, and we are hopeful that our initial theoretical effort toward collective entrepreneurship will provide a foundation for later extensions in the literature to account for these subtleties.

For an interesting antecedent to the KSTE distinction between firms and entrepreneurs, see Hébert and Link’s (2009) discussion of Adam Smith’s and Jeremy Bentham’s contrasting views of the entrepreneur.

For expository reasons, we reduce the dynamic, uncertain problem of maximizing expected profits to a static, deterministic one. See Knight’s (1921) classic work on risk and uncertainty for a justification of this approach.

The assumption that potential revenue (and later appropriability and costs) is a function of n is a simplifying assumption intended to proxy for the complex matching process by which business enterprises identify and partner with other business enterprises in ways that are to the mutual advantage to those business enterprises.

Economically usable knowledge includes the results of the entrepreneurial discovery process that may result in novel applications of technology and forms of output.

Anand and Khanna (1996) argue that the inability to fully appropriate the value of an innovation is due to the presence of weak property rights that arise because of an inability to specify the context and boundaries of knowledge in a manner that makes violation of those property rights verifiable. Cohen (1994) notes that this inability to fully appropriate the value of the research may, if severe enough, lead to incentive problems in engaging in efficient private-sector collaboration, that is, collaboration that results in more research than would be generated in the absence of the collaboration.

There are, of course, markets for human and technical capital, but the nature of R&D in a business enterprise is likely to be more focused on the development side and therefore more applied and proprietary, while the nature of R&D in a university is likely to be more focused on the research side.

See Baldwin and Link (1998) and Leyden and Link (1999) for empirical analyses based on the latter two effects—a reduction in appropriability and a (reduction) in business enterprise research costs. Clearly, we are only focusing on university-industry factors that affect costs and profits. We acknowledge, as urged by an anonymous referee, that there are other important rationales to consider. He/she is correct, but their inclusion is beyond the scope of our model.

The ensuing discussion assumes that α, ω, and κ are not functions of n. This assumption is made for the sake of model clarity. However, we recognize that these parameters may indeed vary to some degree with the number of private-sector collaborators. One possibility that is plausible and consistent with the conclusions of this article is that the loss in appropriability associated with the presence of a university is smaller for incumbent firms (i.e., those that have a larger number of private-sector collaborators) than for startup entrepreneurs (i.e., those that have a smaller number of private-sector collaborators) so that ∂α/∂n > 0. Likewise, the cost savings associated with collaborating with the university is relatively greater for startup entrepreneurs than for incumbent firms (i.e., ∂κ/∂n < 0). Of course, the issue is an empirical one and deserving of future work.

This is an arc elasticity with the base equal to the level of revenues and costs associated with the absence of university collaboration.

Because \( n^{U * } = n^{ * } \) when \( \alpha \sigma = \kappa \), and because the degree to which \( n^{U * } \) differs from \( n^{ * } \) is a positive, continuous function of the degree to which \( \alpha \sigma \) differs from \( \kappa \), we can illustrate these results in the same change in revenue × change in R&D costs policy space used to summarize the conditions under which a business enterprise will choose to collaborate with the university.

Technically, point A lies in Region 1 below the \( \delta_{c} \kappa - 1 = 0 \) line because α 0 ω < κ (recall that ω and κ equal 1 and α 0 is less than 1), which implies \( n^{U * } < n^{*} \) (see the discussion following Eq. (20)), and \( n^{U * } < n^{*} \) implies that \( \delta_{c} \kappa - 1 < 0 \) (see the discussion following Eq. 15). Intuitively, point A lies in Region 1 below the \( \delta_{c} \kappa - 1 = 0 \) line because the increased loss of appropriability (α 0 < 1) results (given no compensating gains in terms of a lower cost function or increase prospects for revenue) in participating firms reducing their level of collaboration with other business enterprises, and that results in a fall in costs and a (proportionately greater) fall in revenues.

If the iso-budget line B 0 were to cross the ασ = κ line, the university could design a balanced-budget program or even positive-profit program that lies in the upper part of Region 4 in Fig. 11. This would still result in a program that essentially charges a fee to participate (κ > 1), though all business enterprises would find the program attractive. Those that participated would have an incentive to increase the number of private-sector partners. However, because the program would be in the upper part of Region 4, this latter incentive would be weak.

See Wyckoff (1990) for a simple comparative static analysis of budget maximization versus slack maximization.

Our analysis assumes that the university program exists in isolation. However, we recognize that university objectives are likely more complex with multiple objectives and the possibility for fungibility in the funding of multiple programs. Åstebro and Bazzazian (2011), for example, note the potential conflict between university efforts to support local startups and university desire for licensing revenue, and Ehrenberg, Rees, and Brewer (1993) provide evidence of universities using revenues from one program to subsidize others. To the extent universities treat the revenues of various programs as fungible, a research program with somewhat higher costs (on the iso-cost curve B 1 for example) might be possible without a grant. Initial work on a more sophistical model of university objectives suggests that the relative salience to the university of its various programs determines the degree to which funding in one program is used to subsidize others.

Breton and Wintrobe (1982) take a more expansive view of bureaucracy by focusing broadly on policy decisions rather than technical production decisions. The Niskanen literature, which derives from Niskanen (1971) and within which our work fits, focuses on policy as well. However, that focus is primarily from a quantitative perspective (such as the quantity to produce) and not from a qualitative one, such as what should be produced and what the qualities of that output should be. From the perspective of this article, Breton and Wintrobe's work is potentially of greater value for understanding the design of a research program, that is, whether it focuses on the goals of increasing revenues and reducing costs that are identified in this article and what mix (that is where on the iso-cost curve) the program would operate.

Business enterprise support for universities, to the extent it is motivated by profit considerations, is subsumed within the structure of this article’s model. However, as an anonymous referee rightly points out, business support for universities may also be motivated by more uncertain, dynamic, and longer term considerations such as the development and maintenance of relationships, access to future graduates, etc. Such motivations are clearly worthy of inquiry but are beyond the scope of this article.

Åstebro and Bazzazian (2011) in their discussion of university entrepreneurial activity suggest that while there are tensions within universities regarding the balance between traditional academic and entrepreneurial interests, the culture of some universities has adapted to entrepreneurial interests.

Baldwin and Link (1998) provide empirical evidence that research joint ventures with universities tend to be larger than those that do not involve universities and argue that the reason for this is that business enterprises in a large research joint venture (because they already have a large number of research partners) incur relatively little additional loss of appropriability if they also collaborate with a university. Leyden and Link (1999) provide similar evidence and argument for research joint ventures involving governmental labs. In terms of the model in this article, this suggests that university programs may empirically tend to be located in Region 2 and that α may be a positive function of the total number private-sector business enterprises (which in Region 2 would primarily be incumbent firms) that choose to collaborate with the university. See Cohn et al. (1989) for more general evidence of economies of scope in universities.

See also Segerstrom and Zolnierek (1999) for an alternative approach. There are two extensions of the Aghion and Hewitt argument worth noting. First, Morales (2003) extends that argument to the realm of financial capital, arguing that subsidies to financial capital are also growth enhancing, though this time because of improved monitoring. Second, Thesmar and Thoenig (2000) argue that recent decades (if not the past century) have seen an increase in product market volatility and creative destruction that has led to a shift away from fixed capital and unskilled labor and toward skilled labor, that is, higher levels of human capital. Such an argument suggests that universities, beyond their value in creating skilled workers, may provide an important role in acting as matchmaker between skilled workers and firms in the regional economy. See Audretsch et al. (2012) for empirical evidence of this connection with respect to the use of graduate students.

A classic description of this pattern can be found in Fisher (1932).

For evidence of other links between R&D and macroeconomic fluctuations, see Alexopoulos (2011).

References

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30.

Adams, J. D. (1990). Fundamental stocks of knowledge and productivity growth. Journal of Political Economy, 98(4), 673–702.

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351.

Alexopoulos, M. (2011). Read all about it!! What happens following a technology shock? American Economic Review, 101(4), 1144–1179.

Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1–2), 11–26.

Anand, B. N., & Khanna, T. (1996). Intellectual property rights and contract structure (Working Paper #3, Working Paper Series H). New Haven: Yale School of Management.

Åstebro, T. B., & Bazzazian, N. (2011). Universities, entrepreneurship and local economic development. In M. Fritsch (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship and Regional Development. New York: Edward Elgar.

Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. E. (2005). Does the knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship hold for regions? Research Policy, 34(8), 1191–1202.

Audretsch, D. B., Leyden, D. P., & Link, A. N. (2012). Universities as research partners in publicly supported entrepreneurial firms. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 21(5–6), 529–545. doi:10.1080/10438599.2012.656523.

Babbage. (2011). MIT and the art of innovation. The Economist. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/blogs/babbage/2011/01/mit_and_art_innovation.

Baldwin, W. L., & Link, A. N. (1998). Universities as research joint venture partners: Does size of venture matter? International Journal of Technology Management, 15(8), 895–913.

Berman, E. M. (1990). The economic impact of industry-funded university R&D. Research Policy, 19(4), 349–355.

Blumenthal, D., Gluck, M., Lewis, K. S., Stoto, M. A., & Wise, D. (1986). University-industry research relationships in biotechnology: Implications for the university. Science, 232(4756), 1361–1366.

Bonaccorsi, A., & Piccaluga, A. (1994). A theoretical framework for the evaluation of university-industry relationships. R&D Management, 24(3), 229–247.

Bozeman, B., Hardin, J., & Link, A. N. (2008). Barriers to the diffusion of nanotechnology. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 17(7–8), 751–753.

Braunerhjelm, P., Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2010). The missing link: Knowledge diffusion and entrepreneurship in endogenous growth. Small Business Economics, 34(2), 105–125.

Breton, A., & Wintrobe, R. (1982). The logic of bureaucratic conduct: an economic analysis of competition, exchange, and efficiency in private and public organizations. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Campbell, T. I. D. (1997). Public policy for the 21st century: Addressing potential conflicts in university-industry collaboration. The Review of Higher Education, 20(4), 357–379.

Coates, D., & Humphreys, B. R. (2002). The supply of university enrollments: University administrators as utility maximizing bureaucrats. Public Choice, 110(3–4), 365–392.

Coates, D., Humphreys, D. R., & Vachris, M. A. (2004). More evidence that university administrators are utility maximizing bureaucrats. Economics of Governance, 5(1), 77–101.

Cockburn, I., Henderson, R. (1997). Public-private interaction and the productivity of pharmaceutical research (NBER Working Paper 6018).

Cohen, L. (1994). When can government subsidize research joint ventures? Politics, economics, and limits to technology policy. American Economic Review, 84(2), 159–163.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1989). Innovation and learning: The two faces of R&D. The Economic Journal, 99(397), 569–596.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). The implications of spillovers for R&D and technology advance. In V. K. Smith & A. N. Link (Eds.), Advances in applied micro-economics. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Cohen, W. M., Florida, R., Randazzese, L., & Walsh, J. (1997). Industry and the academy: Uneasy partners in the cause of technological advance. In R. Noll (Ed.), Challenge to the university. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Cohn, E., Rhine, S. L., & Santos, M. C. (1989). Institutions of higher education as multi-product firms: Economies of scale and scope. Review of Economics and Statistics, 71(2), 284–290.

Council on Competitiveness. (1996). Endless frontiers, limited resources: U.S. R&D policy for competitiveness. Washington, DC: Council on Competitiveness.

Ehrenberg, R. G., Rees, D. I., & Brewer, D. J. (1993). How would universities respond to increased federal support for graduate students? In C. Clotfelter & M. Rothschild (Eds.), Studies of supply and demand in higher education (pp. 183–210). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Feller, I. (1990). Universities as engines of R&D-based economic growth: They think they can. Research Policy, 19(4), 335–348.

Fisher, I. (1932). Booms and depressions: Some first principles. New York: Adelphi.

Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable (GUIRR. (2006). Guiding principles for university-industry endeavors. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Hall, B. H. (2004). University-industry research partnerships in the United States. In J.-P. Contzen, D. Gibson, & M. V. Heitor (Eds.), Rethinking science systems and innovation policies. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.

Hall, B. H., Link, A. N., Scott, J. T. (2000). Universities as research partners (NBER Working Paper 7643).

Hall, B. H., Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2003). Universities as research partners. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(2), 485–491.

Hébert, R. F., & Link, A. N. (2009). A history of entrepreneurship. New York: Routledge.

Henderson, R., Jaffe, A. B., Trajtenberg, M. (1995). Universities as a source of commercial technology: A detailed analysis of university patenting 1965-1988 (NBER Working Paper No. 5068).

Hertzfeld, H. R., Link, A. N., & Vonortas, N. S. (2006). Intellectual property protection mechanisms in research partnerships. Research Policy, 35(6), 825–838.

Howitt, P., & Aghion, Philippe. (1998). Capital accumulation and innovation as complementary factors in long-run growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 3(2), 111–130.

Jaffe, A. (1989). Real effects of academic research. American Economic Review, 79(5), 957–978.

Klevorick, A. K., Levin, R. C., Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1995). On the sources and significance of interindustry differences in technological opportunities. Research Policy, 24(2), 185–205.

Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty, and profit. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Layson, S. K., Leyden, D. P., & Neufeld, J. R. (2008). To admit or not to admit: The question of research park size. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 17(7/8), 691–699.

Lee, Y. S. (2000). The sustainability of university-industry research collaboration: An empirical assessment. Journal of Technology Transfer, 25(2), 111–133.

Leyden, D. P., & Link, A. N. (1999). Federal laboratories as research partners. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 17(4), 575–592.

Leyden, D. P., & Link, A. N. (2013). Collective entrepreneurship: The strategic management of Research Triangle Park. In D. P. Audretsch & M. L. Walshok (Eds.), Creating competitiveness: Entrepreneurship and innovation policies for growth (pp. 176–185). MA: Northampton.

Leyden, D. P., Link, A. N., & Siegel, D. S. (2008). A theoretical and empirical analysis of the decision to locate on a university research park”. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 55(1), 23–28.

Link, A. N. (1996). Research joint ventures: Patterns from Federal Register filings. Review of Industrial Organization, 11(5), 617–628.

Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2005). Universities as partners in U.S. research joint ventures. Research Policy, 34(3), 385–393.

Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2007). The economics of university research parks. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(4), 661–674.

Link, A. N., & Welsh, D. H. B. (2013). From laboratory to market: On the propensity of young inventors to form a new business. Small Business Economics, 40(1), 1–7.

Lööf, H., & Broström, A. (2008). Does knowledge diffusion between university and industry increase innovativeness? Journal of Technology Transfer, 33(1), 73–90.

Mansfield, E. (1991). Academic research and industrial innovation. Research Policy, 20(1), 1–12.

Mansfield, E. (1992). Academic research and industrial innovation: A further note. Research Policy, 21(3), 295–296.

Mansfield, E., & Lee, J.-Y. (1996). The modern university: Contributor to industrial innovation and recipient of industrial R&D support. Research Policy, 25(7), 1047–1058.

Michelacci, C. (2003). Low returns to R&D due to the lack of entrepreneurial skills. Economic Journal, 113(484), 207–225.

Morales, M. F. (2003). Financial intermediation in a model of growth through creative destruction. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 7(3), 363–393.

Morgan, R. P. (1998). University research contributions to industry: The faculty view. In P. D. Blair & R. A. Frosch (Eds.), Trends in Industrial Innovation: Industry Perspectives & Policy Implications. Research Triangle Park, NC: Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society.

Mowery, D. C., Teece, D. J. (1996). Strategic alliances and industrial research. In R. S. Rosenbloom, W. J. Spencer (Eds.), Engines of innovation: U.S. industrial research at the end of an era. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Niskanen, W. A. (1971). Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

Pissarides, C. A. (1990). Equilibrium unemployment theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development (R. Opie, Trans.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press (Original work published 1912).

Segerstrom, P. S., & Zolnierek, J. M. (1999). The R&D incentives of industry leaders. International Economic Review, 40(3), 745–766.

Siegel, D., Waldman, D., Link, A. N. (1999). Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the productivity of university technology transfer offices: An exploratory study (NBER Working Paper No. 7256).

State Science and Technology Institute (SSTI). (2008). A resource guide for technology-based economic development. Washington, DC: Economic Development Administration.

Tassey, G. (2008). Globalization of technology-based growth: The policy imperative. Journal of Technology Transfer, 33(6), 560–578.

Thesmar, D., & Thoenig, M. (2000). Creative destruction and firm organization choice. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4), 1201–1237.

Van de Ven, A. H. (1993). A community perspective on the emergence of innovations. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 10(1–2), 23–51.

Wyckoff, P. G. (1990). The simple analytics of slack-maximizing bureaucracy. Public Choice, 67(1), 35–47.

Zeckhauser, R. (1996). The challenge of contracting for technological information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 93(23), 12743–12748.

Zucker, L. G., Darby, M., Armstrong, J. (1994). Intellectual capital and the firm: The technology of geographically localized knowledge spillovers (NBER Working Paper 4946).

Acknowledgments

This article was presented at the Workshop on Academic Policy and the Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship, sponsored by the Competence Center for Global Business Management and the CisAlpino Institute for Comparative Studies in Europe, and held 20–21 August 2012 at the University of Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany. Special thanks to Zoltan Acs, Maksim Belitski, David B. Audretsch, Christopher Hayter, Marcel Hülsbeck, Mirjam Knockaert, Erik E. Lehmann, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leyden, D.P., Link, A.N. Knowledge spillovers, collective entrepreneurship, and economic growth: the role of universities. Small Bus Econ 41, 797–817 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9507-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9507-7