Abstract

In this article we explore the impact of a series of factors, including creativity, intellectual property rights activities, new business formation, and the provision of amenities, on economic growth for 103 Italian provinces over the period spanning 2001 to 2006. Provincial growth rates are measured in terms of employment growth and value-added growth. The findings reveal that an increase in the number of firms active in the creative industries and net entry have a positive effect on regional employment growth. The share of legal immigrants is also found to positively impact employment growth. A high number of university faculties is found to lead to less employment growth, whereas trademarks, patents, cultural amenities, and industrial districts have no significant effect. Value-added growth is for a large part determined by employment growth, but no additional productivity-enhancing effects of the factors discussed are found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Mellander and Florida (2011) identify a number of conventional and less conventional measures of human capital and ‘talent’ in factors such as the presence of universities, amenities or service diversity, openness, and tolerance.

Consistent with Barzel’s (1989) view, it is likely that creative individuals decide to use patents, trademarks, and registered designs—when not too costly—to acquire IPRs on their creative outputs. In this respect, one might find evidence that systematic recourse to IPR protection is more common in those regions in which creative workers tend to cluster since, due to their compatibility with a variety of locations, they will display a marked preference for acquiring property rights on the achievements of their activities, in view of a possible transfer to other regions (compare Acs 2002).

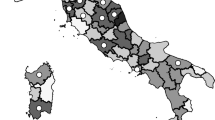

Article 114 of the Italian Constitution introduced three different levels of autonomy and three different orders of decentralization for the government: regions, provinces (and metropolitan provinces), and municipalities. Provinces are sub-regional levels of government with only statutory, regulatory, and administrative competences: they cannot approve statutes or law. According to the basic principles of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) established by Eurostat and used by the European Commission, Italian provinces are NUTS three regions. Even though a number of new provinces were created in 2006, bringing their total number to 107, for the purposes of this paper we have focused only on the 103 provinces (provincial territories) in existence at the beginning of the study by adjusting data to conform with the original 103.

This finding suggests that provinces in the traditionally laggard Southern regions are not yet involved in a significant learning and catching-up process. Partial exceptions are the provinces of Caserta (Campania), Taranto (Puglia), Crotone (Calabria), Ragusa (Sicilia), and Oristano (Sardegna) for value-added growth and those of Reggio Calabria (Calabria), Ragusa, and Oristano for employment growth.

Comprising those central and north-eastern regions in which industrial districts traditionally flourished, and small and medium-sized enterprises active in traditional consumer goods industries represent the bulk of manufacturing.

The main sources of data are: ISTAT, Movimprese (Union of the Italian Chambers of Commerce), and UIBM (Italian Patents and Trademarks Office).

We decided not to use controversial composite measures such as the Creativity Index submitted by Florida (2002). For a discussion, see Storper and Scott (2009). According to the relevant literature and different studies on the creative and cultural sector (e.g., European Commission 2005), we restricted our creative sector to the following industries: (1) activities related to printing (NACE 225); (2) software consultancy and supply (NACE 7222); (3) architectural and engineering activities, including industrial design and related technical consultancy (NACE 742); (4) advertising (NACE 744); (5) fashion design (NACE 7487); (6) artistic and literary creation and interpretation (NACE 9231).

The number of registered designs and models is much lower than the number of trademarks. In fact, over the entire period, the former accounts, on average, for just 4% of the total number of trademarks and designs and models granted by the UIBM.

Over the entire period patents represent on average 74% of the total number of patents and utility models granted by UIBM.

Mizzau and Montanari (2008) discuss the case of Piedmont’s music district as an example of a cultural district. They also use movie tickets per inhabitant as a measure of local demand for artistic and cultural products.

Other diversity measures are the Index of Fractionalization and the Index of Cultural Diversity, which respectively reflect the variety and the share and variety of the foreign population (workers) in the region considered. For a discussion of points of strength and weakness of the various measures, see Audretsch et al. (2010).

These authors used a specific definition of industrial districts, comprising only the ‘traditional’ ones (i.e., present since the first period of diffused industrialization following World War II) located in just 22 of the 103 Italian provinces (Unioncamere 2002).

Note that we do not apply a random effects approach since we incorporate lagged dependent variables into our model. The assumption behind a random effects approach that the individual effects are independent of the explanatory variables can therefore not hold.

In order to test whether the creative class is more attracted to highly urbanized regions, we also used population density and the interaction between population density and Δcreative and NetEntryt as explanatory variables. However, consistent with Boschma and Fritsch (2009), no evidence was forthcoming that the creative class is attracted to highly urbanized regions per se. The results are available from the authors upon request.

This might be also indication that informal business strategies such as secrecy and lead time may provide stronger protection (compare Scotchmer 2004, Chap. 9).

Pursuing the harmonization of tertiary education systems throughout Europe, soon after the signature in Bologna of a joint declaration on 19 June 1999, 29 European governments agreed to create a European Area of Tertiary Education with the purpose of enhancing the international competitiveness of the Member States. Accordingly, as early as the academic year 2001–2002, Italian universities started to reorganize their traditional courses of study to fit the international Bachelor/Master system.

One may suggest that the implementation of the Bologna process has apparent shortcomings in terms of promoting creativity and diversity. As stated by Audretsch (2007, p. 143): “…while the European universities spent decades equalizing their programs to ensure equal opportunities for all […] in America, colleges and universities were busy experimenting, creating new programs, finding new approaches and new ways to deliver education, and creating new opportunities for students and researchers, all spurred on by competition in the great race to attain an excellent reputation”.

We note that in most cases: (1) the academic personnel of peripheral faculties comprises commuters who travel daily from the central location of the multi-campus university; (2) that teaching activity alone is performed locally, whereas research is kept at the central location; (3) that the number of students enrolled can be very low (even close to zero).

In 2007, the three countries of origin of the largest groups of foreign immigrants were Romania (625,278, or 18%), Albania (401,949, or 12%), and Morocco (365,908, or 11%).

The inclusion of province fixed effects implies that ‘between’ effects are left unaccounted for. For example, there may be effects of certain amenities that are relatively constant over time ‘hidden’ in the fixed effects.

References

Acs, Z. J. (2002). Innovation and the growth of cities. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Acs, Z. J., & Megyesi, M. I. (2009). Creativity and industrial cities: A case study of Baltimore. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 21, 421–439.

Acs, Z. J., & Varga, A. (2002). Geography, endogenous growth and innovation. International Regional Science Review, 25, 132–148.

Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., Carlsson, B., & Braunerhjelm, P. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32, 15–30.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). The economic implications of learning by doing. Review of Economic Studies, 29, 155–173.

Audretsch, D. B. (2007). The new entrepreneurial society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional Studies, 38, 949–959.

Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2005). Entrepreneurship capital and regional growth. Annals of Regional Science, 39, 457–469.

Audretsch, D. B., & Thurik, A. R. (2000). Capitalism and democracy in the 21st Century: From the managed to the entrepreneurial economy. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 10, 17–34.

Audretsch, D. B., Santarelli, E., & Vivarelli, M. (1999a). Start-up size and industrial dynamics: Some evidence from Italian manufacturing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 17, 965–983.

Audretsch, D. B., Santarelli, E., & Vivarelli, M. (1999b). Does start-up size influence the likelihood of survival? In D. Audretsch & R. Thurik (Eds.), Innovation, industry evolution and employment (pp. 280–296). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Audretsch, D. B., Dohse, D., & Niebuhr, A. (2010). Cultural diversity and entrepreneurship: A regional analysis for Germany. Annals of Regional Science, 45, 55–85.

Bagnasco, A. (1977). Tre Italie: la problematica territoriale dello sviluppo italiano. Bologna: il Mulino.

Barzel, Y. (1989). Economic analysis of property rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Batabyal, A. A., & Nijkamp, P. (2010). Richard Florida’s creative capital in a trading regional economy: A theoretical investigation. Annals of Regional Science, 44, 241–250.

Becker, G. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. New York: Columbia University Press for NBER.

Beesley, M. E., & Hamilton, R. T. (1984). Small firms’ seedbed role and the concept of turbulence. Journal of Industrial Economics, 33, 217–231.

Berry, C. R., & Glaeser, E. L. (2005). The divergence of human capital levels across cities. Papers in Regional Science, 84, 407–444.

Boschma, R., & Fritsch, M. (2009). Creative class and regional growth: Empirical evidence from seven European countries. Economic Geography, 85, 425–442.

Bun, M. G. J., & Carree, M. A. (2005). Bias-corrected estimation in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 23, 200–210.

Callejon, M., & Segarra, A. (1998). Business dynamics and efficiency in industries and regions: The case of Spain. Small Business Economics, 13, 253–271.

Camagni, R. (2008). Regional competitiveness: Towards a concept of territorial capital. In R. Capello, R. Camagni, B. Chizzolini, & U. Fratesi (Eds.), Modelling regional scenarios for the enlarged Europe (pp. 33–47). Heidelberg: Springer SBM.

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2008). The lag structure of the impact of business ownership on economic performance in OECD countries. Small Business Economics, 30, 101–110.

Choi, Y. R., & Phan, P. H. (2006). The influences of economic and technology policy on the dynamics of new firm formation. Small Business Economics, 26, 493–503.

D’Amuri, F., & Peri, G. (2010). Immigration and occupations in Europe. Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM) WP (10/26). London: University College.

de Palo, D., Faini, R., & Venturini, A. (2006). The social assimilation of immigrants. Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) discussion paper no. 5992. Washington D.C.: CEPR

Deller, S. C., Lledo, V., & Marcouillier, D. W. (2008). Modeling regional economic growth with a focus on amenities. Review of Urban and Regional Development Studies, 20, 1–21.

European Commission. (2005). Future of creative industries. Foresight working document series no. EUR21471. Brussels: European Commission.

Federico, S., & Minerva, G. A. (2008). Outward FDI and local employment growth in Italy. Review of World Economics, 144, 295–324.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class. New York: Basic Books.

Florida, R., & Gates, G. (2001). Technology and tolerance—the importance of diversity to high-technology growth. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Florida, R., Mellander, C., & Stolarick, K. (2008). Inside the black box of regional development—human capital, the creative class and tolerance. Journal of Economic Geography, 8, 615–649.

Foresti, G., Guelpa, F., & Trenti, S. (2009). “Effetto distretto”: Esiste ancora? Intesa Sanpaolo, Collana Ricerche no. R09-01. Turin: Intesa Sanpaolo

Fritsch, M. (2008). How does new business formation affect regional development? Introduction to the special issue. Small Business Economics, 30, 1–14.

Fritsch, M., & Mueller, P. (2004). Effects of new business formation on regional development over time. Regional Studies, 38, 961–975.

Fujita, M., & Thisse, J. F. (2002). Economics of agglomeration: Cities, industrial location, and regional growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Geroski, P. A., & Jacquemin, A. (1985). Industrial change, barriers to mobility, and European industrial policy. Economic Policy, 1, 169–204.

Giovannetti, E., Neuhoff, K., & Spagnolo, G. (2007). Trust and virtual districts: Evidence from the Milan internet exchange. Metroeconomica, 58, 436–456.

Glaeser, E., Kallal, H., Scheinkman, J., & Schleifer, A. (1992). Growth of cities. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 1126–1152.

Glaeser, E., Kolko, J., & Saiz, A. (2001). Consumer city. Journal of Economic Geography, 1, 27–50.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91, 481–510.

Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 71, 3–17.

Howkins, J. (2001). The creative economy. How people make money from ideas. London: Penguin Books.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York: Random House.

Jovanovic, B., & Rousseau, P. L. (2001). Why wait? A century of life before IPO. American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings), 91, 336–341.

Knudsen, B., Florida, R., Stolarick, K., & Gates, G. (2008). Density and creativity in US regions. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 98, 461–478.

Kobayashi, N. (2008). An empirical study about the impact of knowledge accumulation on the development of regional industry. Kwansei Gakuin University, discussion paper series no. 39. Tokyo: Kwansei Gakuin University

Lee, S. Y., Florida, R., & Acs, Z. J. (2004). Creativity and entrepreneurship: A regional analysis of new firm formation. Regional Studies, 38, 879–891.

Lucas, R. (2009). Ideas and growth. Economica, 76, 1–19.

Martin, Ph., & Ottaviano, G. I. P. (2001). Growth and agglomeration. International Economic Review, 42, 947–969.

Mellander, C., & Florida, R. (2011). Creativity, talent, and regional wages in Sweden. Annals of Regional Science, 46.

Mendonça, S., Pereira, T. S., & Godinho, M. M. (2004). Trademarks as an indicator of innovation and industrial change. Research Policy, 33, 1385–1404.

Mizzau, L., & Montanari, F. (2008). Cultural districts and the challenge of authenticity: The case of Piedmont, Italy. Journal of Economic Geography, 8, 651–673.

Morrison, A. (2008). Gatekeepers of knowledge within industrial districts: Who they are, how they interact. Regional Studies, 42, 817–835.

Paci, R., & Usai, S. (2000). The role of specialisation and diversity externalities in the agglomeration of innovative activities. Rivista Italiana degli Economisti, 2, 237–268.

Piergiovanni, R., & Santarelli, E. (2001). Patents and the geographic localization of R&D spillovers in French manufacturing. Regional Studies, 35, 697–702.

Prusa, T. J., & Schmitz, J. A., Jr. (1991). Are new firms an important source of innovation? Economics Letters, 35, 339–342.

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone. Journal of Democracy, 6, 65–78.

Putnam, R. D. (2006). E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century. The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30, 137–174.

Regini, M. (Ed.). (2009). Malata e denigrata: l’università italiana a confronto con l’Europa. Rome: Donzelli.

Santarelli, E., Carree, M. A., & Verheul, I. (2009). Unemployment and firm entry and exit: An update on a controversial relationship. Regional Studies, 43, 1061–1073.

Santarelli, E., & Sterlacchini, A. (1994). New firm formation in Italian industry: 1985–89. Small Business Economics, 6, 95–106.

Saxenian, A. (1994). Regional advantage: Culture and competition in Silicon Valley and route 128. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. American Economic Review, 51, 1–17.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). Theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Scotchmer, S. (2004). Innovation and incentives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Simonton, D. K. (1999). Origins of genius. New York: Oxford University Press.

Storper, M., & Scott, A. J. (2009). Rethinking human capital, creativity and urban growth. Journal of Economic Geography, 9, 147–167.

Unioncamere. (2002). Osservatorio Unioncamere sulla Demografia delle Imprese. Rome: Unioncamere.

Acknowledgments

Enrico Santarelli acknowledges financial support from MIUR (PRIN 2006, ‘Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Competitiveness of Italian Firms in the High-Tech Industries’; protocol #2006132439) and from the Max Planck Institute of Economics, Entrepreneurship, Growth and Public Policy Group. We thank seminar participants at University of Cassino, Friedrich Schiller University Jena and Polytechnic of Torino, Ferran Vendrell-Herrero and participants at the Workshop on ‘Entrepreneurship and Regional Competitiveness’ held at Deusto University San Sebastian, Alex Coad and participants at the DIME Workshop on ‘Markets and Firm Dynamics: From Micro Patterns to Aggregate Behaviors’ held at Université des Antilles et de la Guyane, and participants at the XXXVI Annual E.A.R.I.E. Conference (Ljubljana) for comments. We also thank two anonymous referees for helpful suggestions. The views expressed by Roberta Piergiovanni do not necessarily reflect those of Istat.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piergiovanni, R., Carree, M.A. & Santarelli, E. Creative industries, new business formation, and regional economic growth. Small Bus Econ 39, 539–560 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9329-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9329-4