Abstract

Using a large panel of Italian firms, spanning the years from 1995 to 2003, this study investigates the relationship between bank debt and non-financial SMEs’ performance, evaluating whether and to what extent this link is affected by the degree of competition characterising the local credit market where firms operate. Controlling for inertia, unobserved heterogeneity and the endogeneity of some performance determinants, we find that the (negative) impact of bank debt on firms’ performance is weaker for firms running in more competitive banking markets. We interpret this result as evidence that a more intense banking competition may lead to better credit conditions for small and medium-sized firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a recent empirical investigation on the relationship between leverage and corporate performance, see Weill (2008).

For an overview of theoretical models assuming that banks are identical and competitive, and generating equilibrium (type II) credit rationing, see Parker (2002). After reviewing the empirical evidence on this phenomenon, the author is sceptical of the existence of credit rationing and calls for further investigation of this issue. Also Cressy (2004, p. 26) reckons that: "despite the mountain of theoretical literature suggesting the abstract possibility of credit constraint, it does not appear in general to be an important empirical phenomenon”.

On a theoretical ground, Boot and Thakor (2000) reach a conclusion in contrast to Petersen and Rajan (1995), arguing that competition can increase investments in relationship lending—as these latter represent a way for banks to offer a differentiated product that is less subject to price competition. Empirical support to this result is provided by Elsas (2005).

If a bank can costly use a screening technology which allows to discriminate firms according to their quality, rival banks—though cannot directly observe the outcome of the screening test—can extract information about the screened firms by observing whether the bank extends or denies the loan.

Financing obstacles are measured by a variable having a natural order (from 1 to 4), drawn from a survey question.

The following figures, drawn from the Bank of Italy annual reports (1991−2007), provide an idea of the main transformations that have occurred so far. From 1990 to 2006, the number of banks operating in Italy has dropped from 1,064 to 793, whereas bank branches have grown from 17,721 to 32,337. In the same period, 444 mergers and 205 acquisitions—among domestic credit institutions—were completed (excluding operations that involved the same bank more than once).

Also Angelini and Cetorelli (2003) show that, after the deregulation process, the Italian banking industry has experienced a substantial increase in the degree of competition.

It is worth noticing that local banks have been traditionally prevalent in the Italian banking system (they numbered more than 800 in 1990 and almost 450 at the end of 2006), with a quite homogeneous diffusion in the country. Most of them are cooperative banks (BCC) and Popolari banks. For a detailed discussion on this point, see De Bonis et al. (1994) and Masciandaro (1996).

A large amount of studies on this topic has reached controversial conclusions both on the theoretical and empirical field. According to the Structure-Conduct-Performance paradigm, structural changes leading to concentration in an industrial sector may facilitate collusive behaviour among firms and, therefore, a reduction in the degree of competition. On the other hand, the Efficient-Structure Hypothesis claims that a greater concentration emerges as a consequence of a more vigorous competition in the market, as the most efficient firms might increase their market shares at the expense of their less efficient competitors. For reviews on empirical studies, concerning the banking sector, see Gilbert and Zaretsky (2003) and Berger et al. (2004).

A related analysis concerns bank lending rules (for a discussion see Cressy 2004).

More generally, see Cressy (2004, p. 22) for a discussion on small businesses’ problems with the use of outside equity as alternative source of finance to debt.

Vesala (1995) proves that the same result holds for monopolistic competition without the threat of entry.

For an analysis concerning the problems in measuring market power for dynamic oligopoly models, see Corts (1999).

Indeed, as Panzar and Rosse (1987) clarify, this hypothesis is necessary for the cases of perfect competition and monopolistic competition, while it does not constitute a requirement in the case of monopoly.

For the sake of completeness, other hypotheses on which the H-statistic is based have to be acknowledged. Indeed, it assumes perfect competition in input markets, which may be a restrictive hypothesis in the case of deposits. In fact, there are reasons to doubt that the Italian market for deposits is perfectly competitive (Italian Competition Authority 2007; Cerasi 2007), although—as already mentioned—it is widely documented that banking competition in Italy has heavily increased, as a consequence of the transformations undergone by the sector in the recent past. When applied to the banking sector, the Panzar and Rosse methodology relies also on other restrictive hypotheses—such as the assumption of homogeneity in the cost structure across banks and the hypothesis that the latter are profit maximising single-product firms producing intermediation services (De Bandt and Davis 2000, and Shaffer 2004). Furthermore, the maturity structure of banks’ asset portfolios might imply a downward bias in the estimated elasticities, as fixed rate contracts with longer maturities prevent banks from direct price adjustments. This latter could be a relevant drawback when comparing banking systems of different countries.

The specification of this model is close to that used by De Bandt and Davis (2000).

These latter variables are potentially correlated with past values of the idiosyncratic error, but are not correlated to its present and future values. A strictly exogenous variable is uncorrelated with past, present and future values of the error term. In Eq. 4, if it appears plausible that the current value of a regressor (such as tangible assets) is influenced by past shocks to profitability, that variable is treated as predetermined. When a variable (such as firm’s market power) is likely to be determined simultaneously along with the profitability, it is treated as endogenous. As a result, we treat as exogenous only variables controlling for local market characteristics (population, real per capita growth and bad loans on total loans) and a few variables controlling for firm characteristics (total assets, age and the lag of the expense in research and development). See Sect. 5.1 for a robustness check concerning this choice.

This assumption is verified by two tests for first and second order serial correlation, in the first difference residuals. Indeed, if the errors in level are characterised by lack of serial correlation, the error in differences is expected to display first-order autocorrelation and to be uncorrelated to all other lags. Moreover, it is appropriate to test the overidentifying restrictions through a Sargan test of orthogonality between the extra instruments and the residuals.

In order to account for the presence of potential outliers, we drop, for each variable involved in the econometric analysis, the observations lying in the first and last half percentile of the distribution.

The principal component method allows combining the information contained in our three (highly correlated) measures of profitability. The new variable is the linear combination of the original set of variables, where the weights are chosen so as to maximise the variance explained by the composite index. Prior to the analysis, ROA, ROE and ROS have been standardised in order to avoid that the variable with the highest variance dominates the resulting index.

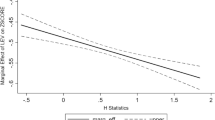

Although not individually significant, the interaction term is jointly significant with the bank debt variable when implementing an F-test. Such a discrepancy between individual and joint significance is usually interpreted as a symptom of multicollinearity (see Wooldridge 2003 and Brambor et al. 2006) induced by the inclusion of an interaction term. As Brambor et al. (2006) highlight, “even if there really is high multicollinearity and this leads to large standard errors on the model parameters, it is important to remember that these standard errors are never in any sense ‘too’ large—they are always the ‘correct’ standard errors. High multicollinearity simply means that there is not enough information in the data to estimate the model parameters accurately and the standard errors rightfully reflect this”.

It is worth recalling that values of the H-statistic lower than zero and greater than one are equivalent to zero and one, respectively, from an economic perspective.

See Sect. 3.2 for the marginal effect and standard error formulas.

The HHI has been computed as: \( {\hbox {HHI}}_{p} = \sum {\left( {ms_{ip} } \right)}^{2}, \) where \( ms_{ip} = \left( {D_{ip} /D_{p} } \right) \) is the deposit market share for each branch office of bank i in the province p, and \( D_{p} = \sum\nolimits_{i} {D_{ip} }.\) Deposits (D) at the provincial level have been obtained by using the criterion illustrated in Sect. 3.1. It is worth noting that, as Petersen and Rajan (1995, p. 418) argue, the HHI calculated on deposits represents a good proxy for competition in the loan markets if the empirical investigation involves firms that largely borrow from local markets, that is if credit markets are local for the firms under consideration. As we claim in Sects. 1 and 3, this is the case for our sample units.

Another approach to correct for generated regressors is the bootstrap method (see, for instance, Agostino-Trivieri 2008; Benfratello et al. 2006). Here, we take the Jackknife approach because the bootstrap alternative was too time-consuming. Moreover, as Fan and Wang (1996) argue, “the disparity between Jackknife and bootstrap results is primarily affected by the size of a sample to which the two techniques are applied. When the sample is large, the difference from the two approaches is small, or even negligible”.

One reason is that they can be manipulated according to the managers’ (or the owner-managers’) interests.

It is worth mentioning that, when our dependent variable is a proxy of firm size (as for net sales and employees, both divided by total assets), the estimating equations omit the measures of size (log of total assets). In the other two cases, columns 3 and 4 of Table 6, the dependent variable is in log form (log of net sales, and log of the number of employees). Since a lagged dependent variable is always included in the regressors set, we can interpret the regressors coefficients as effects in terms of (sales and employee) growth (see, for instance, Oliveira and Fortunato 2006).

These latter checks are here omitted and available upon request.

References

Agostino, M. R., & Trivieri, F. (2008). Banking competition and SMEs bank financing. Evidence from the Italian provinces. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 8(1), 33–53.

Angelini, P., & Cetorelli, N. (2003). The effects of regulatory reform on competition in the banking industry. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 35(5), 663–684.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–297.

Avery, R. B., & Samolyk, K. A. (2000). Bank consolidation and the provision of banking services: The case of small commercial loans. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Working Paper.

Bank of Italy. (1991–2007). Annual report. Rome.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2004). Bank competition and access to finance: International evidence. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 36(3), 627–648.

Benfratello, L., Schiantarelli, F., & Sembenelli, A. (2006). Banks and innovation: Microeconometric evidence on Italian firms. IZA Discussion Paper No. 2032.

Bikker, J. A., & Haaf, K. (2002). Competition, concentration and their relationship: An empirical analysis of the banking industry. Journal of Banking and Finance, 26, 2191–2214.

Black, S. E., & Strahan, P. E. (2002). Entrepreneurship and bank credit availability. The Journal of Finance, LVII(6), 2807–2833.

Berger, A. N., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Levine, R., & Haubrich, J. G. (2004). Bank concentration and competition: An evolution in the making. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 36(3), 433–451.

Berger, A. N., Goldberg, L. G., & White, L. J. (2001). The effects of dynamic changes in bank competition on the supply of small business credit. European Finance Review, 5, 115–139.

Berger, A. N., Kashyap, A. K., & Scalise, J. M. (1995). The transformation of the U.S. banking industry: What a long, strange trip it’s been. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (pp. 55–218).

Berger, A. N., Miller, N. H., Petersen, M. A., Rajan, R. G., & Stein, J. C. (2005). Does function follow organization form? Evidence from the lending practices of large and small banks”. Journal of Financial Economics, 76(2), 237–269.

Berger, A. N., Saunders, A., Scalise, J. M., & Udell, G. F. (1998). The effects of bank mergers and acquisitions on small business lending. Journal of Financial Economics, 50, 187–229.

Bonaccorsi di Patti, E., & Dell’Ariccia, G. (2004). Bank competition and firm creation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 36(2), 225–252.

Bonaccorsi di Patti, E., & Gobbi, G. (2001). The changing structure of local credit markets: Are small business special? Journal of Banking and Finance, 25, 2209–2237.

Bond, S., & Meghir, C. (1994). Dynamic investment models and the firm’s financial policy. Review of Economic Studies, 61(2), 197–222.

Boot, A., & Thakor, A. (2000). Can relationship banking survive competition? The Journal of Finance, LV(2), 679–713.

Brambor, T., Clarck, W., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Cao, M., & Shi, S. (2000). Screening, bidding, and the loan market tightness. Wharton School for Financial Institutions, Centre for Financial Institutions, Working Paper, 09.

Carbò Valverde, S., Humphrey, D. B., & Rodriguez, F. R. (2003). Deregulation, bank competition and regional growth. Regional Studies, 37(3), 227–237.

Cerasi, V. (2007). Più concorrenza nel mercato dei depositi italiani: una riflessione sull’indagine conoscitiva dell’Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato. Economia e Politica Industriale, 2, 169–179.

Cesarini, F. (2003). Il rapporto banca-impresa. Paper presented at the workshop Impresa, risparmio e intermediazione finanziaria: aspetti economici e profili giuridici, Trieste, 24-25 ottobre 2003.

Cetorelli, N. (2001). Competition among banks: Good or bad? Economic Perspectives, 2, 38–48.

Cetorelli, N. (2003). Life-cycle dynamics in industrial sectors: The role of banking market structure. Quarterly Review, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 85, 135–147.

Cetorelli, N., & Gambera, M. (2001). Banking market structure financial dependence and growth: International evidence from industry data. Journal of Finance, 56(2), 617–648.

Cetorelli, N., & Peretto, P. (2000). Oligopoly banking and capital accumulation (p. 12). Working Paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Cetorelli, N., & Strahan, P. E. (2006). Finance as a barrier to entry: Bank competition and industry structure in local U.S. markets. The Journal of Finance, LXI(1), 437–461.

Corts, K. S. (1999). Conduct parameters and the measurement of market power. Journal of Econometrics, 88(2), 227–250.

Corvoisier, S., & Gropp, R. (2002). Bank concentration and retail interest rates. Journal of Banking and Finance, 26, 2155–2189.

Costi, R. (2007). L’ordinamento bancario. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Costi, R., & Messori, M. (2005). Per lo sviluppo. Un capitalismo senza rendite e con capitale. Bologna. Ù: Il Mulino.

Cressy, R. (2004). Credit constraints on small business: Theory versus evidence. International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 1(4), 515–538.

De Bandt, O., & Davis, E. P. (1999). A cross-country comparison of market structures in European banking. Working Paper 7, European Central Bank.

De Bandt, O., & Davis, E. P. (2000). Competition, contestability and market structure in European banking sectors on the eve of EMU. Journal of Banking and Finance, 24, 1045–1066.

De Bonis, R. (2003). Le concentrazioni bancarie: una sintesi. In M. Messori, R. Tamburini, & A. Zazzaro (Eds.), Il sistema bancario italiano (pp. 149–182). Carocci, Roma.

De Bonis, R., Manzone, B., & Trento, S. (1994). La proprietà cooperativa. Teoria, storia e il caso delle banche popolari. Tema di discussione 238. Roma: Banca d’Italia.

De Young, R., Goldberg, L. G., & White, L. J. (1999). Youth, adolescence, and maturity of banks: Credit availability to small business in an era of banking consolidation. Journal of Banking and Finance, 23, 463–492.

Elsas, R. (2005). Empirical determinants of relationship lending. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 14, 32–57.

Fan, X., & Wang, L. (1996). Comparability of Jackknife and Bootstrap results: An investigation for a case of canonical correlation analysis. Journal of Experimental Education, 64, 173–189.

FinMonitor. (2006). Rapporto semestrale su fusioni e aggregazioni tra gli intermediari finanziari in Europa. Bergamo: University of Bergamo.

Geroski, P. A., & Jacquemin, A. (1988). The persistence of profits: A European comparison. Economic Journal, 98, 375–389.

Giacomelli, S., & Trento, S. (2005). Proprietà, controllo e trasferimenti nelle imprese italiane. Cosa è cambiato nel decennio 1993–2003? Bank of Italy, Temi di discussione n. 550.

Gilbert, R. A., & Zaretsky, A. M. (2003). Banking antitrust: Are the assumptions still valid? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review (pp. 1–24).

Goddard, J. A., & Wilson, J. O. S. (1999). The persistence of profit: A new empirical interpretation. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 17(5), 663–687.

Goddard, J. A., & Wilson, J. O. S. (2007). Measuring competition in banking: A disequilibrium approach. Working Paper.

Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. (1982). Corporate financial structure and managerial incentives. In J. McCall (Ed.), The economics of information and uncertainty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Guzman, M. (2000). Bank structure, capital accumulation and growth: A simple macroeconomic model. Economic Theory, 16, 421–455.

Hauswald, R., & Marquez, R. (2006). Competition and strategic information acquisition in credit markets. Review of Financial Studies, 19(3), 967–1000.

Hempell, H. (2002). Testing for competition among German banks. Discussion Paper 04. Economic Research Centre of the Deutsche Bundesbank.

Italian Competition Authority. (2007). Indagine conoscitiva riguardante i prezzi alla clientela dei servizi bancari. Rome.

Jayaratne, J., & Strahan, P. E. (1998). Entry restrictions, industry evolution and dynamic efficiency: Evidence from commercial banking. Journal of Law and Economics, 41, 239–274.

Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76, 323–339.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360.

Koutsomanoli-Fillipaki, A., & Staikouras, C. H. (2006). Competition and concentration in the new European banking landscape. European Financial Management, 12(3), 443–482.

Majumdar, S., & Chhibber, P. (1999). Capital structure and performance. Evidence from a transition economy on an aspect of corporate governance. Public Choice, 98, 287–305.

Marquez, R. (2002). Competition, adverse selection, and information dispersion in the banking industry. Review of Financial Studies, 15, 901–926.

Masciandaro, D. (1996). La specificità delle banche popolari. In D. Masciandaro & F. Riolo (Eds.), Quali banche in Italia? Mercati, assetti proprietari e controlli (pp. 153–183). Milano: Edibank.

Messori, M. (2001). La concentrazione del settore bancario: effetti sulla competitività e sugli assetti proprietari. Quaderni CEIS, 151, 1–65.

Mueller, D. C. (1977). The persistence of profits above the norm. Economica, 44, 369–380.

Nickell, S., & Nicolitsas, D. (1999). How does financial pressure affect firms. European Economic Review, 43, 1435–1456.

Oliveira, B., & Fortunato, A. (2006). Firm growth and liquidity constraints: A dynamic analysis. Small Business Economics, 27, 139–156.

Pagan, A. (1984). Econometric issues in the analysis of regressions with generated regressors. International Economic Review, 25, 221–247.

Pagano, M. (1993). Financial markets and growth. An overview. European Economic Review, 37, 613–622.

Panzar, J. C., & Rosse, J. N. (1987). Testing for monopoly equilibrium. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 35(4), 443–456.

Parker, S. C. (2002). Do banks ration credit to new enterprises? And should governments intervene? Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 49(2), 162–195.

Peek, J., & Rosengren, E. S. (1998). Bank consolidation and small business lending: It’s not just bank size that matters. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22, 799–819.

Petersen, M., & Rajan, R. G. (1995). The effect of credit market competition on lending relationships. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 407–443.

Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88, 559–586.

Saccomanni, F. (2006). Il ruolo delle banche italiane per lo sviluppo del Sistema paese. Intervento alla X Convention ABI, Roma.

Shaffer, S. (1982). A non-structural test for competition in financial markets. In Proceedings of a Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago (pp. 225–243).

Shaffer, S. (1998). The winner’s curse in banking. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 7, 359–392.

Shaffer, S. (2004). Patterns of competition in banking. Journal of Economics and Business, 56, 287–313.

Stiglitz, J., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. American Economic Review, 71, 393–410.

Strahan, P. E., & Weston, J. P. (1998). Small business lending and the changing structure of the banking industry. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22, 821–845.

Vesala, J. (1995). Testing for competition in banking: Behavioural evidence from Finland. Helsinki: Bank of Finland.

Waring, G. F. (1996). Industry differences in the persistence of firm-specific returns. American Economic Review, 86(5), 1253–1265.

Weill, L. (2008). Leverage and corporate performance: Does institutional environment matter? Small Business Economics, 30(3), 251–265.

Williams, J. (1987). Perquisites, risk, and capital structure. The Journal of Finance, XLII, 29–49.

Wooldridge, J. (2003). Introductory econometrics. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

Zarutskie, R. (2004). New evidence on bank competition, firm borrowing and firm performance. Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, Mimeo.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to an anonymous referee for his/her valuable comments and suggestions on a previous version of the paper. We also thanks Francesca Gagliardi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agostino, M., Trivieri, F. Is banking competition beneficial to SMEs? An empirical study based on Italian data. Small Bus Econ 35, 335–355 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9154-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9154-6