Abstract

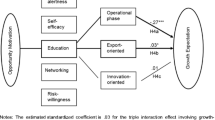

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor model combines insights on the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship at the national (adult working-age population) level with literature in the Austrian tradition. The model suggests that the relationship between national-level new business activity and the institutional environment, or Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions, is mediated by opportunity perception and the perception of start-up skills in the population. We provide a theory-grounded examination of this model and test the effect of one EFC, education and training for entrepreneurship, on the allocation of effort into new business activity. We find that in high-income countries, opportunity perception mediates fully the relationship between the level of post-secondary entrepreneurship education and training in a country and its rate of new business activity, including high-growth expectation new business activity. The mediating effect of skills perception is weaker. This result accords with the Kirznerian concept of alertness to opportunity stimulating action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that we are not suggesting that the GEM model would constitute a ‘theory’ in its own right. To provide for meaningful interpretation of the GEM data, it is nevertheless important to discuss how the model relates to influential schools of thought within the domain of entrepreneurship.

The box labeled New Firms was originally labeled Business Dynamics (Reynolds et al. 1999), then from 2000 to 2003 was labeled Business Churning (Reynolds et al. 2000, 2001a, b, 2002, 2003), and from 2004 to 2005 was labeled New Firms (Acs et al. 2005; Minniti et al. 2006). In the latest iteration (Bosma et al. 2008), it is labeled Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity.

We would suggest adding the word “Economic” to this box in the GEM model.

For an alternative reconciliation of the Schumpeterian and Kirznerian positions, which the GEM model could also accommodate, see Leibenstein (1987).

Strictly speaking, Baumol’s main focus was on the allocation of entrepreneurs into ‘productive’ and ‘unproductive’ activities. Baumol’s notion of the allocation of effort can easily be extended to consider the allocation of effort into entrepreneurship in general.

In a 1978 update of his earlier paper, Leibenstein renamed this “innovational” entrepreneurship (Leibenstein 1978, p. 40).

In relation to motivation, we note a recent review of entrepreneurial motivation by Shane et al. (2003) in which the authors urge researchers to control for opportunity in studies of motivation. The GEM model may act as a useful guide in this respect.

The focus of the GEM model is on what Baumol terms productive entrepreneurship. Thus, it is not relevant to the GEM model whether, as Baumol suggests, some individuals are entrepreneurial and others are not, and the question is what makes entrepreneurs choose productive over unproductive or destructive entrepreneurship, or whether, as von Mises suggests, anyone can behave entrepreneurially and the question is what prompts people to behave entrepreneurially rather than non-entrepreneurially.

Indeed, in some countries, entrepreneurs are not permitted to trade until they can prove they have acquired such facilities. See, for example, http://www.doingbusiness.org/ExploreTopics/StartingBusiness/Details.aspx?economyid=195, accessed 21 June 2008.

The latter has been traditionally referred to by GEM as “Cultural and Social Norms”. To distinguish it clearly from universal values, consideration might be given to changing the label to Entrepreneurial Attitudes.

We do not consider the effect of entrepreneurship education and training on motivation further in this paper.

The GEM 2000–2006 dataset covered the following high-income countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom and USA. In addition, the dataset included the following low-income countries, defined as countries with GDP per capita less than US $20,000: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Croatia, Ecuador, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Jordan, Latvia, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Although Baumol sees his independent innovator as a synonym for Schumpeter’s entrepreneur, we interpret Schumpeter’s entrepreneur as the fulfiller of the function ‘new business activity;’ “not only those “independent” businessmen in an exchange economy who are usually so designated” (Schumpeter 1934, p. 74).

In the data there were a number of unrealistically high job-expectation figures. We carefully examined the shapes of job expectation distributions and determined that any start-up attempt expecting more than 996 jobs could be set to zero without biasing the distribution.

http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28—accessed in August 2007.

Correlation matrix is available from the authors upon request.

We ran all tests using both fixed-effect and random-effect specification, as well as specifying robust and non-robust standard errors (i.e., with and without assuming heteroscedasticity in error terms). No major differences in results were observed, and none of the significant influences reported in this paper showed sensitivity to analysis specification. As a further check of robustness, we also employed a large number of different variable combinations, as well as different model specifications. The core findings, as reported in Tables 1–4, were remarkably insensitive to model specifications.

An interesting pattern in the data, not reported here because of space and data limitations, concerned the differing role of primary and higher educational institutions in low- and high-income economies, respectively. Where we observed a mediating effect for higher education EFC, opportunity perception and entrepreneurship in high-income economies, a similar mediation was observed for primary education EFC, opportunity perception and TEA in low-income economies. This may suggest that the role of the educational system varies according to the level of economic development.

References

Acs, Z. (2006). How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innovations, 1, 97–107.

Acs, Z. J., & Amorós, J. E. (2008). Entrepreneurship and competitiveness dynamics in Latin America. Small Business Economics, 31(3), this issue. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9133-y.

Acs, Z. J., Arenius, P., Hay, M., & Minniti, M. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2004 executive report. Babson Park, MA: Babson College; London, UK: London Business School.

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsh, D. B. (1990). Innovation and small firms. Boston: MIT Press.

Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., Braunerhjelm, P., & Carlsson, B. (2004). The missing link: The knowledge filter, entrepreneurship and endogenous growth. Discussion Paper, No. 4783, December. London, UK: Center for Economic Policy Research.

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2006). A knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Discussion Paper, No. 5326, December. London, UK: Center for Economic Policy Research.

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S. & Hessels, J. (2008a). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31(3), this issue. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9135-9.

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Klapper, L. F. (2008b). What does “entrepreneurship” data really show? Small Business Economics, 31(3), this issue. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9137-7.

Acs, Z., & Szerb, L. (2007). Entrepreneurship, economic growth and public policy. Small Business Economics, 28(2/3), 109–122.

Acs, Z., & Varga, A. (2005). Entrepreneurship, agglomeration and technological change. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 323–334.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ardichvili, A. A., Cardozo, R. R., & Ray, S. S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 105–123.

Aronsson, M. (2004). Education matters—but does entrepreneurship education? An interview with David Birch. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3(3), 289–292.

Audretsch, D. B., Grilo, I., & Thurik, A. R. (2007a), Explaining entrepreneurship and the role of policy: A framework. In D. B. Audretsch, I. Grilo, & A. R. Thurik (Eds.), The handbook of research on entrepreneurship policy (pp. 1–17). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Audretsch, D. B., Grilo, I., & Thurik, A. R. (Eds.). (2007b). Handbook of research on entrepreneurship policy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Audretsch, D., Keilbach, M., & Lehman, E. (2006). Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Autio, E. (2005). GEM 2005 report on high-expectation entrepreneurship. London: GERA.

Autio, E. (2007). GEM 2007 report on high-growth entrepreneurship. London: GERA.

Autio, E., & Acs, Z. (2007, June). Individual and country-level effects on growth aspiration in new ventures. Paper presented at the Babson Entrepreneurship Research Conference, Madrid.

Baltagi, B. H., & Wu, P. X. (1999). Unequally spaced panel data regressions with AR(1) disturbances. Econometric Theory, 15, 814–823.

Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 893–921.

Baumol, W. J. (2002). The free-market innovation machine. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Baumol, W. J. (2003). On Austrian analysis of entrepreneurship and my own. In R. Koppl (Ed.), Austrian economics and entrepreneurial studies (Vol. 6, pp. 57–66). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Béchard, J.-P., & Grégoire, D. (2005). Entrepreneurship education research revisited: The case of higher education. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4(1), 22–49.

Bertrand, Y. (1995). Contemporary theories and practice in education. Madison, WI: Atwood Publishing.

Bitzenis, A., & Nito, E. (2005). Obstacles to entrepreneurship in a transition business environment: The case of Albania. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(4), 564–578.

Bosma, N., Jones, K., Autio, E., & Levie, J. (2008). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2007 executive report. London: Global Entrepreneurship Research Association.

Botero, J., Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2004). The regulation of labor. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 1339–1382.

Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 18(4), 63–77.

Brenner, R. (1992). Entrepreneurship and business ventures in the new commonwealth. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(6), 431–439.

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2000). The life cycle of the U.S. tire industry. Southern Economic Journal, 67(2), 254–287.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., & Reynolds, P. D. (1996). Exploring start-up event sequences. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(3), 151–166.

Cetorelli, N., & Strahan, P. E. (2006). Finance as a barrier to entry: Bank competition and industry structure in local U.S. markets. The Journal of Finance, 61(1), 437–461.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 295–316.

Choo, S., & Wong, M. (2006). Entrepreneurial intention: Triggers and barriers to new venture creations in Singapore. Singapore Management Review, 28(2), 47–64.

Clarysse, B., & Bruneel, J. (2007). Nurturing and growing innovative start-ups: The role of policy as integrator. R&D Management, 37(2), 139–149.

Corbett, A. C. (2005). Experiential learning within the process of opportunity identification and exploitation. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 29(4), 473–491.

Cotis, J. P. (2007, January). Entrepreneurship as an engine for growth: Evidence and policy challenges. Paper presented at GEM Forum: Entrepreneurship: Setting the Development Agenda, London.

Dahles, H. (2005). Culture, capitalism and political entrepreneurship: Transnational business ventures of the Singapore Chinese in China. Culture & Organization, 11(1), 45–58.

Davidsson, P., & Henrekson, M. (2002). Determinants of the prevalence of start-ups and high-growth firms. Small Business Economics, 19(2), 81–104.

Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2003). Does business planning facilitate the development of new ventures? Strategic Management Journal, 24(12), 1165–1185.

DeTienne, D., & Chandler, G. (2004). Opportunity identification and its role in the entrepreneurial classroom: A pedagogical approach and empirical test. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3(3), 242–257.

Directorate-General Enterprise. (2004). Benchmarking enterprise policy: Results from the 2004 scoreboard. Commission Staff Working Document SEC (2004) 1427, November

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 1–35.

Dolinsky, A. L., Caputo, R. K., Pasumarty, K., & Quazi, H. (1993). The effects of education on business ownership: A longitudinal study of women. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 18(1), 43–53.

Dreher, A., & Gassebner, M. (2007). Greasing the wheels of entrepreneurship? Impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. KOF WP 166. Zurich: KOF Swiss Economic Institute.

Dubini, P. (1989). The influence of motivations and environment on business start-ups: Some hints for public policies. Journal of Business Venturing, 4(1), 11–26.

Eckhardt, J. T., & Shane, S. A. (2003). Opportunities and entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 29(3), 333–349.

Etzioni, A. (1987). Entrepreneurship, adaptation and legitimation. Journal of Economic Behavior, 8, 175–189.

Fayolle, A. (2000). Exploratory study to assess the effects of entrepreneurship programs on French student entrepreneurial behaviors. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 8(2), 169–184.

Fiet, J. O. (2000). The theoretical side of teaching entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 16, 1–24.

Fischer, E., & Reuber, A. R. (2003). Support for rapid-growth firms: A comparison of the views of founders, government policymakers, and private sector resource providers. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(4), 346–365.

Fisman, R., & Sarria-Allende, V. (2004). Regulation of entry and the distortion of industrial organization. WP 10929. National Bureau of Economic Research

Garavan, T. N., & O’Cinneide, B. (1994). Entrepreneurship education and training programmes: A review and evaluation part 1. Journal of European Industrial Training, 18(8), 3–12.

Gartner, W., Bird, B., & Starr, J. (1992). Acting as if: Differentiating entrepreneurial from organizational behaviour. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 16(3), 13–32.

George, G. G., & Zahra, S. A. S. (2002). Culture and Its consequences for entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 26(4), 5–8.

Geroski, P. A. (1989). Entry, innovation and productivity growth. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 71(4), 572–578.

Geroski, P. A. (1995). What do we know about entry? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13, 421–440.

Ghosh, P., & Cheruvalath, R. (2007). Indian female entrepreneurs as catalysts for economic growth and development. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 8(2), 139–148.

Goldfarb, B., & Henrekson, M. (2003). Bottom-up versus top-down policies towards the commercialization of university intellectual property. Research Policy, 32(4), 639–658.

Grilo, I., & Irigoyen, J. M. (2006). Entrepreneurship in the EU: To wish and not to be. Small Business Economics, 26(4), 305–318.

Hansen, J., & Sebora, T.C. (2003). Applying principles of corporate entrepreneurship to achieve national economic growth. Advances in the Study of Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Growth, 14, 69–90

Hart, D. M. (Ed.). (2003). The emergence of entrepreneurship policy: Governance, start-ups, and growth in the U.S. knowledge economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hawkins, D. I. (1993). New business entrepreneurship in the Japanese economy. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(2), 137–150.

Hayek, F. A. v. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530.

Hayek, F. A. v. (1978). Competition as a discovery procedure. In F. A. v. Hayek (Ed.), New studies in philosophy, politics, economics, and the history of ideas (pp. 179–190). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hayton, J. C. J., George, G. G., & Zahra, S. A. S. (2002). National culture and entrepreneurship: A review of behavioral research. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 26(4), 33–52.

Heinonen, J., & Poikkijoki, S.-A. (2006). An entrepreneurial-directed approach to entrepreneurship education: Mission impossible? Journal of Management Development, 25(1), 80–94.

Helms, M. H. (2003). The challenge of entrepreneurship in a developed economy: The problematic case of Japan. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 8(3), 247–264.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishers.

Hofstede, G., Noorderhaven, N. G., Thuirik, A. R., Wennekers, A. R. M., Uhlaner, L., & Wildeman, R. E. (2003). Culture’s role in entrepreneurship: Self-employment out of dissatisfaction. In J. Uljin & T. Brown (Eds.), Innovation, entrepreneurship and culture: The interaction between technology, progress and economic growth (pp. 162–203). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Honig, B. (2004). Entrepreneurship education: Toward a model of contingency-based business planning. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3(3), 258–273.

House, R. J. (1998). A brief history of GLOBE. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 13(3/4), 230–240.

Hunt, S., & Levie, J. (2004). Culture as a predictor of entrepreneurial activity. In W. D. Bygrave, C. G. Brush, P. Davidsson, J. O. Fiet, P. G. Greene, R. T. Harrison, M. Lerner, G. D. Meyer, J. Sohl, & A. Zacharakis (Eds.), Frontiers of entrepreneurship research 2003 (pp. 171–185). Babson Park, MA: Babson College.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and post modernization: Culture, economic and political change in 43 societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Javidan, M., House, R. J., Dorfman, P. W., Hanges, P. J., & Sully de Luque, M. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: A comparative review of GLOBE’s and Hofstede’s approaches. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 897–914.

Kaufmann, P. J., Welsh, D. H. B., & Bushmarin, B. V. (1995). Locus of control and entrepreneurship in the Russian Republic. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 20(1), 43–57.

Kawai, H., & Urata, S. (2002). Entry of small and medium enterprises and economic dynamism in Japan. Small Business Economics, 18, 41–52.

Keuschnigg, C., & Nielsen, S. B. (2001). Public policy for venture capital. International Tax and Public Finance, 8(4), 557–572.

Keuschnigg, C., & Nielsen, S. B. (2002). Tax policy, venture capital, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Public Economics, 87(1), 175–203.

Keuschnigg, C., & Nielsen, S. B. (2004). Start-ups, venture capitalists, and the capital gains tax. Journal of Public Economics, 88(5), 1011–1042.

Kirzner, I. (1979). Perception, opportunity and profit. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kirzner, I. (1985). The perils of regulation: A market process approach. In I. Kirzner (Ed.), Discovery and the capitalist process (pp. 119–149). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kirzner, I. (1997a). How markets work: Disequilibrium, entrepreneurship and discovery. IEA Hobart Paper 133. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Kirzner, I. (1997b). Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: An Austrian approach. Journal of Economic Literature, 35, 60–85.

Klapper, L., Laeven, L., & Rajan, R. (2006). Entry regulation as a barrier to entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 82, 591–629.

Klepper, S. (1996). Entry, exit, growth, and innovation over the product life cycle. American Economic Review, 86, 562–583.

Klepper, S. (2002). The capabilities of new firms and the evolution of the US automobile industry. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(4), 645–666.

Klepper, S., & Sleeper, S. (2005). Entry by spinoffs. Management Science, 51(8), 1291–1306.

Kögel, T. (2004). Did the association between fertility and female employment within OECD countries really change its sign? Journal of Population Economics, 17, 45–65.

Kouriloff, M. (2000). Exploring perceptions of a priori barriers to entrepreneurship: A multidisciplinary approach. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 25(2), 59–79.

Lazear, E. (2004). Balanced skills and entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 94(2), 208–211.

Lazear, E. P. (2005). Entrepreneurship. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(4), 649–680.

Leibenstein, H. (1966). Allocative efficiency vs. X-efficiency. American Economic Review, 56(3), 392–415.

Leibenstein, H. (1968). Entrepreneurship and development. The American Economic Review, 58(2), 72–83.

Leibenstein, H. (1978). General X-efficiency theory and economic development. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Leibenstein, H. (1987). Entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial training and X-efficiency. Journal of Economic Bahavior and Organization, 8, 191–205.

Leibenstein, H. (1995). The supply of entrepreneurship. In G. M. Meier (Ed.), Leading issues in economic development (pp. 273–275). New York: Oxford University Press.

Levie, J. (2006). From business plans to business shaping: Reflections on an experiential new venture creation class. WP 040/2006. London, UK: National Council for Graduate Entrepreneurship.

Levie, J., & Autio, E. (2008). Regulation of entry, rule of law, and entrepreneurship: an international panel study. Hunter Centre for Entrepreneurship working paper. Glasgow, UK: University of Strathclyde.

Levie, J., & Hunt, S. (2005). Culture, institutions and new business activity: Evidence from global entrepreneurship monitor. In S. A. Zahra, C. G. Brush, P. Davidsson, J. Fiet, P. G. Greene, R. T. Harrison, M. Lerner, C. Mason, G. D. Meyer, J. Sohl, & A. Zacharakis (Eds.), Frontiers of entrepreneurship research 2004 (pp. 519–533). Babson Park, MA: Babson College.

Liao, J., Welsch, H. P., & Pistrui, D. (2001). Environmental and individual determinants of entrepreneurial growth: An empirical examination. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 9(3), 253–272.

Lopez-Claros, A., Porter, M. E., Schwab, K., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (2006). The global competitiveness report 2006–2007. London, UK: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Lundström, A., & Stevenson, L. (2005). Entrepreneurship policy: Theory & practice. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Maddy, M. (2000). Dream deferred: The story of a high-tech entrepreneur in a low-tech world. Harvard Business Review, 78(3), 57–69.

Maddy, M. (2004). Learning to love Africa: My journey from Africa to Harvard Business School and back. New York: Harper Business.

Malerba, F., & Orsenigo, L. (1996). Schumpeterian patterns of innovation are technology-specific. Research Policy, 25, 451–478.

Michelacci, C. (2003). Low returns in R&D due to the lack of entrepreneurial skills. The Economic Journal, 113(484), 207–225.

Minniti, M., Bygrave, W. D., & Autio, E. (2006). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2005 executive report. Babson Park, MA: Babson College; London, UK: London Business School.

Murphy, P. J., Kickul, J., Barbosa, S. D., & Titus, L. (2007). Expert capital and perceived legitimacy: Female-run entrepreneurial venture signalling and performance. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 8(2), 127–138.

Murphy, K. M., Schleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1991). The allocation of talent: Implications for growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 503–530.

Parker, S. C. (2006). Entrepreneurship, self-employment, and the labour market. In M. Casson, B. Yeung, A. Basu, & N. Wadeson (Eds.), Oxford handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 435–460). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peterman, N., & Kennedy, J. (2003). Enterprise education: Influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 28, 129–144.

Puffer, S. M., & McCarthy, D. J. (2001). Navigating the hostile maze: A framework for Russian entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Executive, 15(4), 24–36.

Reynolds, P. D., Bosma, N., Autio, E., De Bono, N., Servais, I., Lopez-Garcia, P., et al. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205–231.

Reynolds, P. D., Bygrave, W. D., Autio, E., Cox, L. W., & Hay, M. (2002). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2002 executive report. Babson Park, MA: Babson College; London, UK: London Business School.

Reynolds, P. D., Bygrave, W. D., Autio, E., et al. (2003). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2003 executive report. Babson Park, MA: Babson College; London, UK: London Business School.

Reynolds, P. D., Camp, S. M., Bygrave, W. D., Autio, E., & Hay, M. (2001a). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2001 executive report. Babson Park, MA: Babson College; London, UK: London Business School.

Reynolds, P. D., Hay, M., Bygrave, W. D., Camp, S. M., & Autio, E. (2000). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2000 executive report. Babson Park, MA: Babson College; London, UK: London Business School.

Reynolds, P. D., Hay, M., & Camp, M. S. (1999). Global entrepreneurship monitor 1999 executive report. Babson Park, MA: Babson College; London, UK: London Business School.

Reynolds, P. D., Rauch, A., Lopez-Garcia, P., & Autio, E. (2001b). February). Data collection-analysis strategies operations manual. Internal GEM Document. London: London Business School.

Robertson, A., Collins, A., Medeira, N., & Slater, J. (2003). Barriers to start-up and their effect on aspirant entrepreneurs. Education & Training, 45(6), 308–316.

Robinson, P. B., & Sexton, E. A. (1994). The effect of education and experience on self-employment success. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(2), 141–156.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. The Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 71–102.

Ruef, M. (2005). Origins of organizations: The entrepreneurial process (review). Research in the Sociology of Work, 15, 63–100

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1947a). Capitalism, socialism and democracy (2nd ed.). London: George Allen & Unwin.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1947b). The creative response in economic history. Journal of Economic History, 7, 149–159.

Schwartz, S. (1994). Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S.-C. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, methods and applications (pp. 85–119). London: Sage.

Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11(4), 448–469.

Shane, S. (2002). Executive forum: University technology transfer to entrepreneurial companies. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(6), 537–552.

Shane, S. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: The individual-opportunity nexus. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Shane, S., Locke, E., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13, 257–279.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25, 217–226.

Shrader, R., & Siegel, D. S. (2007). Assessing the relationship between human capital and firm performance: Evidence from technology-based new ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 31(6), 893–908.

Smith, B., Peterson, M. F., & Schwartz, S. H. (2002). Cultural values, sources of guidance, and their relevance to managerial behavior. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(2), 188–208.

Spencer, J. W., & Gomez, C. (2004). The relationship among national institutional structures, economic factors, and domestic entrepreneurial activity: A multicountry study. Journal of Business Research, 57, 1098–1107.

Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector. London, UK: Routledge.

Storey, D. J., & Tether, B. S. (1998). Public policy measures to support new technology-based firms in the European Union. Research Policy, 26(9), 1037–1057.

Suzuki, K., Kim, S. H., & Bae, Z. T. (2002). Entrepreneurship in Japan and Silicon Valley: a comparative study. Technovation, 22(10), 595–606.

Trulsson, P. (2002). Constraints of growth-oriented enterprises in the southern and eastern African region. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 7(3), 331–339.

Uhlaner, L. M., & Thurik, A. R. (2007). Post-materialism: A cultural factor influencing total entrepreneurial activity across nations. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 17(2), 161–185.

Van der Horst, R., Nijsen, A., & Gulhan, S. (2000). Regulatory policies and their impact on SMEs in Europe: The case of administrative burdens. In D. Sexton & H. Landstrom (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 128–149). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

van Stel, A., Carree, M., & Thurik, R. (2005). The effect of entrepreneurial activity on national economic growth. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 311–321.

van Stel, A., Storey, D., & Thurik, A. R. (2007). The effect of business regulations on nascent to young business entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(2/3), 171–186.

Volery, T., Doss, T, Mazzarol, T. & Thein, V. (1997, June). Triggers and barriers affecting entrepreneurial intentionality: The case of western Australian nascent entrepreneurs. Paper Presented at 42nd ICSB World Conference, San Francisco

Von Mises, L. (1949). Human action. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Wennekers, S., van Stel, A., Thurik, R., & Reynolds, P. (2005). Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 293–309.

Witt, U. (2002). How evolutionary is Schumpeter’s theory of economic development? Industry and Innovation, 9(1/2), 7–22.

Wright, M., Hmieleski, K. M., Siegel, D. S., & Ensley, M. D. (2007). The role of human capital in technological entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 31(6), 791–806.

Acknowledgements

Both authors contributed equally to the development of this article. They are grateful to Paul Reynolds, David Audretsch and Zoltan Acs and to participants in the 2007 GEM Research Conference, Washington, D.C., for their encouragement and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Items employed in the 2006 National Expert Survey

EFC type | Item code | Item wording |

|---|---|---|

Finance EFC | A01 | In my country, there is sufficient equity funding available for new and growing firms |

Finance EFC | A02 | In my country, there is sufficient debt funding available for new and growing firms |

Finance EFC | A03 | In my country, there are sufficient government subsidies available for new and growing firms |

Finance EFC | A04 | In my country, there is sufficient funding available from private individuals (other than founders) for new and growing firms |

Finance EFC | A05 | In my country, there is sufficient venture capitalist funding available for new and growing firms |

Finance EFC | A06 | In my country, there is sufficient funding available through initial public offerings (IPOs) for new and growing firms |

Policy EFC | B01 | In my country, government policies (e.g., public procurement) consistently favor new firms |

Policy EFC | B02 | In my country, the support for new and growing firms is a high priority for policy at the national government level |

Policy EFC | B03 | In my country, the support for new and growing firms is a high priority for policy at the local government level |

Regulations EFC | B04 | In my country, new firms can get most of the required permits and licenses in about a week |

Regulations EFC | B05 | In my country, the amount of taxes is NOT a burden for new and growing firms |

Regulations EFC | B06 | In my country, taxes and other government regulations are applied to new and growing firms in a predictable and consistent way |

Regulations EFC | B07 | In my country, coping with government bureaucracy, regulations and licensing requirements is not unduly difficult for new and growing firms |

Programs EFC | C01 | In my country, a wide range of government assistance for new and growing firms can be obtained through contact with a single agency |

Programs EFC | C02 | In my country, science parks and business incubators provide effective support for new and growing firms |

Programs EFC | C03 | In my country, there are an adequate number of government programs for new and growing businesses |

Programs EFC | C04 | In my country, the people working for government agencies are competent and effective in supporting new and growing firms |

Programs EFC | C05 | In my country, almost anyone who needs help from a government program for a new or growing business can find what they need |

Programs EFC | C06 | In my country, government programs aimed at supporting new and growing firms are effective |

Primary education EFC | D01 | In my country, teaching in primary and secondary education encourages creativity, self-sufficiency and personal initiative |

Primary education EFC | D02 | In my country, teaching in primary and secondary education provides adequate instruction in market economic principles |

Primary education EFC | D03 | In my country, teaching in primary and secondary education provides adequate attention to entrepreneurship and new firm creation |

Higher education EFC | D04 | In my country, colleges and universities provide good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms |

Higher education EFC | D05 | In my country, the level of business and management education provides good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms |

Higher education EFC | D06 | In my country, the vocational, professional and continuing education systems provide good and adequate preparation for starting up and growing new firms |

R&D transfer EFC | E01 | In my country, new technology, science, and other knowledge are efficiently transferred from universities and public research centers to new and growing firms |

R&D transfer EFC | E02 | In my country, new and growing firms have just as much access to new research and technology as large, established firms |

R&D transfer EFC | E03 | In my country, new and growing firms can afford the latest technology |

R&D transfer EFC | E04 | In my country, there are adequate government subsidies for new and growing firms to acquire new technology |

R&D transfer EFC | E05 | In my country, the science and technology base efficiently supports the creation of world-class new technology-based ventures in at least one area |

R&D transfer EFC | E06 | In my country, there is good support available for engineers and scientists to have their ideas commercialized through new and growing firms |

Business services EFC | F01 | In my country, there are enough subcontractors, suppliers and consultants to support new and growing firms |

Business services EFC | F02 | In my country, new and growing firms can afford the cost of using subcontractors, suppliers and consultants |

Business services EFC | F03 | In my country, it is easy for new and growing firms to get good subcontractors, suppliers and consultants |

Business services EFC | F04 | In my country, it is easy for new and growing firms to get good, professional legal and accounting services |

Business services EFC | F05 | In my country, it is easy for new and growing firms to get good banking services (checking accounts, foreign exchange transactions, letters of credit and the like) |

Market dynamism EFC | G01 | In my country, the markets for consumer goods and services change dramatically from year to year |

Market dynamism EFC | G02 | In my country, the markets for business-to-business goods and services change dramatically from year to year |

Market openness EFC | G03 | In my country, new and growing firms can easily enter new markets |

Market openness EFC | G04 | In my country, the new and growing firms can afford the cost of market entry |

Market openness EFC | G05 | In my country, new and growing firms can enter markets without being unfairly blocked by established firms |

Market openness EFC | G06 | In my country, the anti-trust legislation is effective and well enforced |

Physical infra EFC | H01 | In my country, the physical infrastructure (roads, utilities, communications, waste disposal) provides good support for new and growing firms |

Physical infra EFC | H02 | In my country, it is not too expensive for a new or growing firm to get good access to communications (phone, Internet, etc.) |

Physical infra EFC | H03 | In my country, a new or growing firm can get good access to communications (telephone, Internet, etc.) in about a week |

Physical infra EFC | H04 | In my country, new and growing firms can afford the cost of basic utilities (gas, water, electricity, sewer) |

Physical infra EFC | H05 | In my country, new or growing firms can get good access to utilities (gas, water, electricity, sewer) in about a month |

Entrep culture EFC | I01 | In my country, the national culture is highly supportive of individual success achieved through own personal efforts |

Entrep culture EFC | I02 | In my country, the national culture emphasizes self-sufficiency, autonomy and personal initiative |

Entrep culture EFC | I03 | In my country, the national culture encourages entrepreneurial risk-taking |

Entrep culture EFC | I04 | In my country, the national culture encourages creativity and innovativeness |

Entrep culture EFC | I05 | In my country, the national culture emphasizes the responsibility that the individual (rather than the collective) has in managing his or her own life |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levie, J., Autio, E. A theoretical grounding and test of the GEM model. Small Bus Econ 31, 235–263 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9136-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9136-8