Abstract

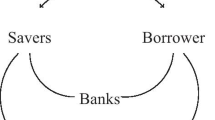

The present paper focuses on professionals as a special group of microenterprises. It explains their characteristics and financial relationships, using data from a survey conducted in Germany in 2002. Consistent with the theory of asymmetric information and relationship lending, we find that these firms maintain a small number of bank relationships, which increases in firm size and age. They tend to choose multiple banking relationships to overcome credit rationing and finance larger loans. Credit risk and the structure of the banking market do not seem to matter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Ongena and Smith (2000b) and Qian and Strahan (2005) for cross sections of countries, Guiso and Minetti (2004) for the US, Cosci and Meliciani (2002) and Detragiache et al. (2000) for Italy, Machauer and Weber (2000) and Harhoff and Körting (1998b) for Germany, Ziane (2003) for France, Neuberger et al. (2006) for Switzerland, Degryse and Ongena (2001) for Norway, Berger et al. (2001b) for Argentina, Berger et al. (2005) for India, Yu and Hsieh (2003) and Fok et al. (2004) for Taiwan, and Ogawa et al. (2005) for Japan.

We use ‘housebank’ and ‘relationship bank’ as synonymous terms. A housebank is usually defined as the major lender of a firm and does not preclude that the firm holds also other bank relationships. For German universal banks, the incidence of a housebank status has been shown to be positively related to the bank’s share of borrower debt financing, but negatively related to the firm’s number of bank relationships (Elsas 2005).

See, however, Baas and Schrooten (2006), who show that the lack of reliable information leads to comparative high interest rates even if a long-term bank–borrower relationship exists.

For empirical evidence, see Brunner and Krahnen (2002), who show that the success probability of a workout of financially distressed firms depends negatively on the number of lending banks. Gilson et al. (1990) and Petersen and Rajan (1994) find that a larger number of creditors worsens the terms of credit and increases the cost of financial distress to small firms.

For an overview, see Ongena and Smith (2000a, pp.243). Medium and larger firms typically hold more than three bank relationships in Germany (Elsas and Krahnen 1998, Machauer and Weber 2000), Argentina (Berger et al. 2001b), Taiwan (Yu and Hsieh 2003, Fok et al. 2004), India (Berger et al. 2005), and the majority of 20 European countries (Ongena and Smith 2000b). While firms in the UK, Norway and Sweden maintain fewer than three bank relationships on average, firms in Italy, Portugal, Belgium and Spain maintain on average 10 or more bank relationships (Ongena and Smith 2000a).

Transaction lending is generally viewed as being focused on informationally transparent borrowers. However, this view is oversimplified, because only one transaction technology (financial statement lending) is focused on transparent borrowers, while other transaction technologies (small business credit scoring, asset-based lending, factoring, fixed-asset lending and leasing) are targeted to opaque borrowers (Berger and Udell 2005).

For empirical evidence, see Carter et al. (2004).

The long-term relationship between banks and small firms in Germany has been strengthened by the increasing bank competition, which induced banks to provide more long-term funds and information to small firms (Audretsch and Elston 2002, p. 6).

Farinha and Santos (2002) find for young firms in Portugal that the chance of substituting a single banking relationship with multiple banking relationships increases with the duration of that relationship. Ongena and Smith (2001) show for Norwegian firms that the probability of ending a bank relationship increases in duration and that small, young and highly leveraged firms maintain the shortest relationships.

The low response rate is likely to be due to the fact that the questionnaire contained some very personal questions and questions about financial matters, which are reluctantly answered online. In Germany, there is still much concern about the safety of the internet, and especially older persons are reluctant to use this medium. In our sample, the mean age of the self-employed persons acting as professionals is 49 years.

In the present sample, investment credits are not only collateralized by real estate (63% of the cases), but also by transfer of property by way of security (25% of the cases), assignment of claims (20% of the cases) and personal guarantees (20% of the cases).

At the time of our survey, the possible advantage of the Basle II rules for small firms, given by lower bank capital requirements for the retail portfolio, had not been discussed yet. For recent research on the effects of the Basle II reform on retail credit markets, see Claessens et al. (2005) and the remaining papers in the respective special issue of the Journal of Financial Services Research.

References

Agarwal, S., & Hauswald, R. (2006). Distance and information asymmetries in lending decisions. Paper Presented at the Conference ‘Financial System Modernisation and Economic Growth in Europe’, Berlin, September 2006.

Akhavein, J., Goldberg, L. G., & White, L. J. (2004). Small banks, small business, and relationships: An empirical study of lending to small farms. Journal of Financial Services Research, 26, 245–261.

Arrow, K. J. (1985). The economics of agency. In J. W. Pratt & R. J. Zeckhauser (Eds.), Principals and agents. The structure of business. Boston, MA.

Audretsch, D. B., & Elston, J. A. (2002). Does firm size matter? Evidence on the impact of liquidity constraints on firm investment behavior in Germany. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20, 1–17.

Baas, T., & Schrooten, M. (2006). Relationship banking and SMEs: A theoretical analysis. Small Business Economics, 27, 127–137.

Bannier, C. E. (2005). Heterogeneous multiple bank financing under uncertainty: Does it reduce inefficient credit decisions? Working paper series: Finance and accounting, Goethe-University Frankfurt/Main No. 49.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (1995). Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance. Journal of Business, 68, 351–381.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2002). Small business credit availability and relationship lending: The importance of bank organisational structure. Economic Journal, 112, F32–F53.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2003). The future of relationship lending. In A. N. Berger & G. F. Udell (Eds.), The future of banking, Westport.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2005). A more complete conceptual framework for financing of small and medium enterprises. World bank policy research working paper, 3795.

Berger, A. N., Goldberg, L. G., & White, L. J. (2001a). The effects of dynamic changes in bank competition on the supply of small business credit. European Finance Review, 5, 115–139.

Berger, A. N., Klapper, L. F., & Udell, G. (2001b). The ability of banks to lend to informationally opaque small businesses. Journal of Banking and Finance, 25, 2127–2167.

Berger, A. N., Klapper, L. F., Soledad Martinez Peria, M., & Zaidi, R. (2005). The effects of bank ownership type on banking relationships and multiple banking in developing economies. Detailed evidence from India. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington DC.

Bhattacharya, S., & Chiesa, G. (1995). Proprietary information, financial intermediation, and research incentives. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 4, 328–357.

BMWi. (2006). Existenzgründungen durch freie Berufe, GründerZeiten 45, Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technologie (Ed.), September 2006.

Bolton, P., & Scharfstein, D. S. (1996). Optimal debt structure and the number of creditors. Journal of Political Economy, 104, 1–25.

Boot, A. W. A. (2000). Relationship banking: What do we know? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 9, 7–25.

Boot, A. W. A., & Thakor, A. V. (1994). Moral hazard und secured lending in an infinitely repeated credit market game. International Economic Review, 35, 899–920.

Boot, A. W. A., & Thakor, A. V. (2000). Can relationship banking survive competition? Journal of Finance, 55, 679–713.

Brunner, A., & Krahnen, J. P. (2002). Multiple lenders and corporate distress: Evidence on debt restructuring. CFS working paper 2001/04, Frankfurt/Main

Carletti, E. (2004). The structure of bank relationships, endogenous monitoring, and loan rates. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13, 58–86.

Carletti, E., Cerasi, V., & Daltung, S. (2004). Multiple-bank lending: Diversification and free-riding in monitoring. CFS working paper 2004/18, Frankfurt/Main.

Carter, D. A., McNulty, J. E., & Verbrugge, J. A. (2004). Do small banks have an advantage in lending? An examination of risk-adjusted yields on business loans at large and small banks. Journal of Financial Services Research, 25, 233–252.

Claessens, S., Krahnen, J., & Lang, W. W. (2005). The Basel II reform and retail credit markets. Journal of Financial Services Research, 28, 5–13.

Commission of the European Communities, 2003, Concerning the definition of micro, small, medium-sized enterprises, Document number C 1422

Cosci, S., & Meliciani, V. (2002). Multiple banking relationships: Evidence form the Italian experience. Manchester School Supplement, 37–54.

Cowling, M. (1999). The incidence of loan collateralization in small business lending contracts: Evidence from the UK. Applied Economics Letters, 6, 291–293.

D’Auria C., Foglia, A., & Reedtz, P. M. (1999). Bank interest rates and credit relationships in Italy. Journal of Banking and Finance, 23, 1067–1093.

Degryse, H., & Ongena, S. (2001). Bank relationships and firm performance. Financial Management, 30, 9–34.

Detragiache, E., Garella, P., & Guiso, L. (2000). Multiple versus single banking relationships: Theory and evidence. Journal of Finance, 55, 1133–1161.

Dewatripont, M., & Maskin, E. (1995). Credit and efficiency in centralized and decentralized economics. Review of Economic Studies, 62, 541–555.

Diamond, D. W. (1984). Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. Review of Economic Studies, 51, 393–414.

Elsas, R. (2005). Empirical determinants of relationship lending. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 14, 32–57.

Elsas, R., & Krahnen, J. P. (1998). Is relationship lending special? Evidence from credit file data in Germany. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22, 1283–1316.

Elsas, R., & Krahnen, J. P. (2002). Collateral, relationship lending and financial distress: An empirical study on financial contracting. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 2540.

Elsas, R., Heinemann, F., & Tyrell, M. (2004). Multiple but asymmetric bank financing: The case of relationship lending. CESifo working paper no. 1251.

Elyasiani, E., & Goldberg, L. G. (2004). Relationship lending: A survey of the literature. Journal of Economics and Business, 56, 315–330.

Farinha, L., & Santos, J. A. C. (2002). Switching from single to multiple bank lending realtionships: Determinants and implications. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 11, 124–151.

Fok, R. C. W., Chang, Y. C., & Lee, W. T. (2004). Bank relationships and their effects on firm performance around the Asian financial crisis: Evidence from Taiwan. Financial Management, 33, 89–112.

Gilson, S. C., Kose, J., & Lang, L. H. P. (1990). Troubled debt restructurings: An empirical study of private reorganization of firms in default. Journal of Financial Economics, 27, 315–353.

Greene, W. H. (2000). Econometric analysis, International Edition, New Jersey.

Guiso, L. (2003). Small business finance in Italy. European Investment Bank Papers, 8, 121–149.

Guiso, L., & Minetti, R. (2004). Multiple creditors and information rights: Theory and evidence from US firms’, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4278.

Hackl, P. (2004). Einführung in die Ökonometrie, München et al.

Hannan, T. H. (2003). Changes in non-local lending to small business. Journal of Financial Services Research, 24, 31–46.

Harhoff, D., & Körting, T. (1998a). Lending relationships in Germany – empirical evidence from survey data. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22, 1317–1353.

Harhoff, D., & Körting, T. (1998b). How many creditors does it take to tango?’ Discussion Paper, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin and Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, Mannheim.

Hauswald, R., & Marquez, R. (2006). Competition and strategic information acquisition in credit markets. Review of Financial Studies, 19, 967–1000.

Hellwig, M. (1991). Banking, financial intermediation and corporate finance. In A. Giovannini & C. Mayer (Eds.), European financial integration pp. (35–63). Cambridge.

Hommel, U., & Schneider, H. (2003). Financing the German Mittelstand. EIB Papers, 7, 52–90.

Hübler, O. (1991). Was unterscheidet Freiberufler, Gewerbetreibende und abhängig Beschäftigte? MittAB (Mitteilungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung) 1/91, 101–114.

Jayaratne, J., & Wolken, J. (1999). How important are small banks to small business lending: New evidence from a survey of small banks. Journal of Banking and Finance, 23, 427–458.

Jean-Baptiste, E. L. (2005). Information monopoly and commitment in intermediary–firm relationships. Journal of Financial Services Research, 27, 5–26.

Koziol, C. (2006). When does single-source versus multiple-source lending matter? International Journal of Managerial Finance, 2, 19–48.

Lehmann, E., & Neuberger, D. (2001). Do lending relationships matter? Evidence from bank survey data in Germany. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 45P, 339–359.

Machauer, A., & Weber, M. (1998). Bank behaviour based on internal credit ratings of borrowers. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22, 1355–1384.

Machauer, A., & Weber, M. (2000). Number of bank relationships: An indicator of competition, borrower quality, or just size? CFS working paper 2000/06, Frankfurt/Main.

Menkoff, L., Neuberger, D., & Suwanaporn, C. (2006). Collateral-based lending in emerging markets: Evidence from Thailand. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30, 1–21.

Neuberger, D., Räthke, S., & Schacht, C. (2006). The number of bank relationships of SMEs: A Disaggregated analysis of changes in the Swiss loan market. Economic Notes, 35(3), 319–353.

Ogawa, K., Sterken, E., & Tokutsu, I. (2005). Bank control and the number of bank relations of Japanese firms, CESIFO working paper no. 1589.

Ongena, S., & Smith, D. C. (2000a). Bank relationships: A review. In P. T. Harker & S. A. Zenios (Eds.), The performance of financial institutions (pp. 221–258). Cambridge University Press.

Ongena, S., & Smith, D. C. (2000b). What determines the number of bank relationships? Cross-country evidence. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 9, 26–56.

Ongena, S., & Smith, D. C. (2001). The duration of bank relationships. Journal of Financial Economics, 61, 449–475.

Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1994). The benefits of lending relationships: Evidence from small business data. Journal of Finance, 49, 3–37.

Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1995). The effect of credit market competition on lending relationships. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 407–433.

Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (2002). does distance still matter? The information revolution in small business lending. Journal of Finance, 57, 2533–2570.

Qian, J., & Strahan, P. E. (2005). How law and institutions shape financial contracts: The case of bank loans. NBER working paper 11052

Rajan, R. G. (1992). Insiders and outsiders: The choice between informed and arms length debt. Journal of Finance, 47, 1367–1400.

Sachverständigenrat. (2004). Erfolge im Ausland – Herausforderungen im Inland. Jahresgutachten 2004/05, Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung, Wiesbaden.

Sachverständigenrat. (2005). Die Chance nutzen – Reformen mutig voranbringen. Jahresgutachten 2005/06, Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung, Wiesbaden.

Sharpe, S. A. (1990). Asymmetric information, bank lending, and implicit contracts: A stylized model of customer relationships. Journal of Finance, 45, 1069–1087.

Stark, J. (2001). Neue Trends in der Unternehmensfinanzierung. Deutsche Bundesbank, Auszüge aus Presseartikeln, 9, 2–6.

Strahan, P. E., & Weston, J. P. (1998). Small business lending and the changing structure of the banking industry. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22, 821–845.

Sturman, M. C. (1999). Multiple approaches to analysing count data in studies of individual differences: The propensity for type I Errors, illustrated with the case of absenteeism prediction. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 59, 414–430.

Vale, B. (1993). The dual role of demand deposits under asymmetric information. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 95, 77–95.

Von Rheinbaben, J., & Ruckes, M. (2004). The number and the closeness of bank relationships. Journal of Banking and Finance, 28, 1597–1615.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT.

Yosha, O. (1995). Disclosure costs and the choice of financing source. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 4, 3–20.

Yu, H., & Hsieh, D. (2003). Multiple versus single banking relationships in an emerging market: Some Taiwanese evidence. In From money lenders to bankers: Evolution of Islamic banking in relation to Judeo Christian and oriental banking traditions, Monash Prato Centre, Prato IT.

Ziane, Y. (2003). Number of banks and credit relationships: Empirical results from french small business data. European Review of Economics and Finance, 2, 33–60.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Robert Hauswald and two referees for helpful suggestions and comments

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neuberger, D., Räthke, S. Microenterprises and multiple bank relationships: The case of professionals. Small Bus Econ 32, 207–229 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9076-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9076-8