Abstract

Recent empirical work has offered strong support for ‘biased pluralism’ and ‘economic elite’ accounts of political power in the United States, according a central role to ‘business interest groups’ as a mechanism through which corporate influence is exerted. Here, we propose an additional channel of influence for corporate interests: the ‘policy-planning network,’ consisting of corporate-dominated foundations, think tanks, and elite policy-discussion groups. To evaluate this assertion, we consider one key policy-discussion group, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). We first briefly review the origins of this organization and then review earlier findings on its influence. We then code CFR policy preferences on 295 foreign policy issues during the 1981–2002 period. In logistic regression analyses, we find that the preferences of more affluent citizens and the CFR were positive, statistically significant predictors of foreign policy outcomes while business interest group preferences were not. These findings are discussed with a consideration of the patterns of CFR ‘successes’ and ‘failures’ for the issues in our dataset. Although a full demonstration of a causal connection between corporate interests, the policy-planning network and policy outcomes requires further research, we conclude that this has been shown to be a plausible mechanism through which corporate interests are represented and that ‘biased pluralism’ researchers should include it in their future investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In their widely cited study, Gilens and Page (2014) delineated four broad theoretical camps on US politics: majoritarian electoral democracy theories, which hold that the will of the electorate is the key influence on policy formation; majoritarian pluralism theories, which argue that the will of the majority asserts itself through conflicts between organised interest groups; economic elite theories, which claim that the views of the wealthiest citizens are disproportionately influential; and biased pluralism theories, which posit that the organised groups created by the wealthy or by businesses are disproportionately successful in the struggle between interest groups. They then evaluated these competing approaches by identifying the policy preferences of average citizens, affluent citizens, mass-based interest groups and business interest groups across a wide array of policy issues – from a dataset of 1779 public opinion survey questions - for the years 1981–2002. Entering all of these different policy preferences into their regression analyses, they found support for both ‘economic elite’ and ‘biased pluralism’ theories of political power: the preferences of citizens at the 90th income percentile (their proxy for ‘economic elites’) and of business interest groups were the most important predictors of policy outcomes. Their findings represent an important contribution to the theory of the distribution of political power in American society. Moreover, by bringing together data on public opinions and interest group preferences for a period of more than two decades, they have helped to develop a new methodological approach for the study of political power in the US.

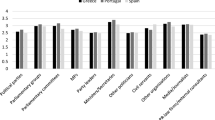

Their findings on the disproportionate influence of ‘economic elites’ have attracted considerable attention and engendered lively discussion and debate (e.g., Branham, Sorka and Wlezien, 2017; Enns, 2015a, 2015b; Gilens, 2015; Gilens and Page, 2016). Here, however, we would like to focus on the other aspect of their findings, concerning ‘biased pluralism.’ We regard their findings as important but suggest that they may actually underestimate corporate influence in politics. This is because their measure of corporate engagement may overlook ways in which corporate interests are represented, at least for certain policy areas. To develop this point, we start by observing that the level of engagement demonstrated by the business groups studied by Gilens and Page varied widely across different policy areas. Table 1 shows the level of engagement for each of the nineteen policy areas in their dataset, as indicated by the percentage of policy questions for which the groups expressed a preference. Both the business and mass-based groups in their dataset were clearly more engaged in some areas than in others. Thus, from the table alone, we would not be surprised to learn that, for example, business interest groups were more influential in shaping policy on campaign financing or taxation than on guns or religious issues during this period.

However, it is also possible that business interests were represented in ways that are not captured by the measure used by Gilens and Page. In this article, we seek to show that this is, in fact, the case – at least, in the area of foreign policy. Business interest groups expressed preferences on only 4.9% of the foreign policy questions in their dataset, suggesting that business interests played only a minor role in the shaping of foreign policy. Our claim, however, is that, despite this low level of engagement by business interest groups, the interests of the corporate community were, in fact, quite well represented in the area of foreign policy during this period. This is so, we argue, due to the efforts of a different type of organization that had clearly stated preferences on all of the foreign policy issues in the dataset: the Council on Foreign Relations, or CFR. Our broader claim is that researchers who restrict their focus to special interest groups or lobbyists may underestimate corporate influence in politics more generally by not including organizations such as the CFR.

Below, we develop this argument in stages. First, we offer a broader theoretical framework for understanding corporate influence. Next, we briefly outline the development of the CFR, reviewing evidence that the Council has both represented the interests of the corporate community and played an influential role in the formation of US foreign policy, including during the period of our study. Finally, in order to provide support for our claim, we repeat the analyses made by Gilens and Page for the subset of foreign policy issues in their database, adding the policy preferences of the CFR.

Theoretical framework: A corporate dominance perspective

The ‘corporate dominance’ approach to politics in the US (Domhoff, 2020, 2022) represents an attempt to provide an understanding of corporate political influence that goes beyond the activities of interest groups. According to this approach, corporate owners and senior executives have, from the early years of the twentieth century to the present time, used both their control of large parts of the economy and their disproportionate political power to become the dominant force in establishing the structure, rules and customs of daily life in the US. Following the rise of the corporation as the predominant economic organization in the late 1800s, as detailed in William Roy’s Socializing Capital: The Rise of the Large Industrial Corporation in America (Roy, 1999), the leaders of the corporate community next moved to develop policy-oriented organizations. In doing so, they split into relatively distinct, organisationally based moderate-conservative and ultraconservative political camps (McLellan and Woodhouse, 1960; Woodhouse and McLellan, 1966)Footnote 1 and this split, has, at times, offered opportunities for other organised power actors. Nonetheless, through their organizations, the corporate community came to have a dominant influence on US politics.

This view is distinct from other prominent sociological theories of US politics. In contrast to more-or-less ‘orthodox’ Marxist theories, it does not hold that corporate domination emerges inevitably from the development of capitalist production (Poulantzas, 1973), but rather that it was the particular outcome of the historical development of political ‘power actors’ in the United States. Unlike ‘historical institutionalist’ theories, which emphasize the roles of autonomous state actors (Skocpol, 2007), the corporate dominance perspective foregrounds the ways in which corporate actors not only directly occupy positions within the state, but also actively shape the institutions of the state to further their own ends.

This broader view of corporate influence holds that the corporate community exerts political influence in four ways: special-interest lobbying, policy-planning, opinion-shaping, and candidate-selection (Domhoff, 2020). Gilens and Page demonstrated the importance of the first process, special-interest lobbying, by showing that the policy preferences of business interest groups significantly predicted policy outcomes across a wide variety of issues. These business interest groups, which comprise the special-interest network, focus primarily on directly lobbying Congressional committees and regulatory agencies that are important in relation to their direct and specific interests. While Gilens and Page focused on a subset of particularly influential business groups, many dozens of such business associations have been formed by the various commercial sectors of the corporate community, such as the American Bankers Association, the National Petroleum Institute, and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (Berry, 1997; McConnell, 1970; Schlozman and Tierney, 1986; Schlozman, Verba and Brady, 2012) We emphasize that these organizations represent only one of the mechanisms through which corporate interests are represented.

In this article, we seek to extend the findings of Gilens and Page with a focus on the second of these mechanisms, namely, policy planning undertaken by the corporate community.Footnote 2 Policy planning is conducted through a network of corporate-financed and corporate-dominated (via memberships on boards of trustees) foundations, think tanks, and elite policy discussion groups (see Fig. 1). This policy-planning network (hereafter, PPN) started to emerge in the early years of the twentieth century and was already deeply enmeshed in the policy-making process by the 1930s. The organizations within this network provide settings within which the general policy interests of the corporate community are articulated and clarified, where conflicts are discussed, where potential representatives are informally recruited for government service, where policy perspectives are disseminated, and where concrete policy proposals are generated. The PPN disseminates policy perspectives, designs policy plans that can be made available to political actors, and selects and promotes experts and potential political candidates whose opinions are friendly to the corporations that fund these networks and dominate the boards of directors of their constituent organizations.

The PPN is largely distinct in its goals and methods from the special-interest network. In contrast to the latter, it functions to distill the more general interests of the corporate community into policy proposals. Earlier research has documented the role played by the PPN in shaping policy in various areas, including climate change (Bonds, 2016), the allocation of natural resources (Alpert and Markusen, 1980), environmental affairs more generally (Downey & Strife, 2010; Gonzalez, 2001), the privatization of schooling (Mintz, 2017), domestic economic issues (Burris, 2008; Peschek, 1987, 2017), and, the focus of the present article, foreign affairs (Van Apeldoorn and De Graaff, 2016; Dreiling and Darves, 2016; Murray, 2017; Whitham, 2016). The present study seeks to contribute to this literature, proposing that mapping the policy preferences of a key organization within the PPN – The Council on Foreign Relations – would provide a useful additional measure of corporate influence that goes beyond measuring the impact of business interest groups.

Policy-discussion groups and the Council on Foreign Relations

Central to the process through which corporate leaders develop and articulate their general interests are the policy-discussion groups within the PPN. Policy-discussion groups bring together corporate leaders, special experts from think tanks and university institutes, and government officials to discuss policy on a wide range of issues, including foreign policy. Their reports carry the status accorded to the prominent corporate directors involved. These groups thus differ from ‘think tanks’, which typically consist of expert employees of organizations focused on particular policy domains. Although some think tanks have, in recent decades, provided informal discussion sessions for the benefit of government experts and elected officials, policy-discussion groups and think tanks remain largely distinct and fulfill different functions. The operations of the policy-planning network are summarised in Fig. 1.

One of these policy-discussion groups, the Council on Foreign Relations, has arguably been the single most important institutional channel through which the corporate community has shaped US foreign policy. Connected to the corporate community through funding and membership, the CFR has shaped US foreign policy both through the flow of reports and studies to the government and through the direct occupation of government offices by CFR members. The CFR attained this uniquely important institutional position during World War II. As this outcome is central to understanding corporate influence on US foreign policy, we briefly outline its development.

The CFR was founded in June 1918, “as a somewhat loose gathering of bankers and other members of the business community in the New York area” (Wala, 1994, pp. 5–7). Wary of isolationist sentiment and interested in expanding international trade in the post-World War I era, they supported the creation of treaties to enable such an expansion and backed the foundation of the League of Nations. In 1920, they invited a group of professors and other experts in foreign affairs to become members and work on projects of mutual interest with the support of the CFR. In 1921, the enlarged CFR that emerged offered a clear statement of its purpose that has guided it ever since:

To afford a continuous conference on international questions affecting the United States, by bringing together experts on statecraft, finance, industry, education and science … [in order to] create and stimulate international thought among the people of the United States, and to this end, to cooperate with the Government of the United States and with international agencies, co-ordinating international activities by eliminating, in so far as possible, duplication of effort, to create new bodies, and to employ such other and further means, as from time to time may seem wise and proper (CFR, 1947).

To meet these goals, the CFR established the journal Foreign Affairs in 1922, which published articles by the leading statesmen of the day and by academic experts, many already affiliated with the CFR. The organization also created informal discussion groups for those who simply wanted to learn more about a topic and to ask basic questions, and – more importantly for our purposes – ‘study groups’ to focus on particular topics (Grose, 1996; Schulzinger, 1984). These study groups were led by ‘rapporteurs’, typically academic experts on the topic in question, and members included business leaders concerned with the topic, as well as current and former statesmen with experience related to it. The study groups thus established direct links between the corporate community and the government. The rapporteurs would often go on to write up a report distilling the study group’s policy suggestions, and these reports were eventually published in Foreign Affairs, or as pamphlets or books with the CFR imprimatur. The reports were sent on to relevant government agencies, and often included in the Congressional record when the leader or another member of the group testified before a Congressional committee. Indeed, generating and disseminating such reports became the central focus of the CFR’s efforts.Footnote 3

Although the CFR brought together academic expertise with corporate financing from its outset, it achieved access to the highest levels of decision-making related to foreign affairs only in the late 1930s (Domhoff, 2020, Ch. 10; Shoup, 1975). Essentially brought in as a partner to the State Department following the start of the war in Europe in September 1939, the CFR established war-peace study groups that, between 1939 and 1942, articulated an internationalist vision for both the conduct of the war and the transition to the post-war world. One of these, the Economic and Financial Group, was tasked with determining the conditions that would allow for a resumption of stable world trade, a challenge made more urgent from May 1940 by the invasion of France and attack on the UK. Faced with exclusion from German-dominated Europe, the group quickly concluded that a ‘Western Hemisphere’ trading bloc would be insufficient, containing too many countries with competitive, rather than complementary, economies (Domhoff, 2020, p. 386). They thus focused on the question of determining the ‘minimum world area’ required for ‘security and economic prosperity’ and, on October 19 of that year, issued a memorandum that was remarkable for its coherence and scope as well as for the degree to which it foreshadowed US foreign policy positions across the entire post-war era, down to the present day. Their position started with the premise that a prosperous global economy – pre-requisite for a prosperous US economy – required sufficient supplies of raw materials and a large number of complementary economies. This could only be realised through an economic ‘Grand Area’ comprised of the western hemisphere as well as the British Empire and the Far East, implying that neither the UK nor Japan could be allowed to exclude the US from their areas of influence. To prevent defections from this ‘Grand Area’ (their own term for this area from the early 1940s, later discontinued), they envisioned two general strategies. On the one hand, monetary, investment and trade arrangements would need to be made to allow the US, the UK and Japan to harmoniously co-exist. On the other hand, attempts by countries to defect and develop exclusive trade zones would need to be thwarted through economic and political pressure and, if necessary, military coercion.

By 1942, evidence from government archives suggests that this worldview had been accepted within the government (Domhoff, 2020, Ch. 10; Shoup, 1975). Although the end of the war brought the need to rebuild and reintegrate Europe, as well as the replacement of Germany and Japan by the Soviet Union and communist movements as the main perceived threats to the world economy, the principles articulated by the CFR study groups continued to steer policy. At the same time, the CFR worked to convince government decision-makers to rebuild Germany as the core of a Western Europe capable of subduing its own national communist movements (Gramer, 1995, 1997; Wala, 1994, Ch. 4).

Working from the key assumptions articulated in the War-Peace Studies, CFR members were central in the construction of all of the pillars of the post-war Pax Americana, including the Marshall Plan, the IMF and the World Bank (Domhoff, 2020, Ch. 10–11, 13; Helleiner, 2014; Hogan, 1987; Steil, 2013; Whitham, 2016). Further, a broad network of experts and policymakers used these principles to navigate policy throughout the post-war period (usually in the face of strong opposition from corporate ultraconservatives), pressing continually for reductions in trade barriers, adjustments to monetary mechanisms and military interventions to prevent countries from departing from the US-led global economy. The clarity, depth and coherence of the corporate-backed CFR’s vision and the extent of its influence at a number of levels, with its leading members often in government positions implementing these plans, reflect its importance in shaping the post-war world.Footnote 4

In addition to the documentation provided by historical studies of the CFR, the hypothesised connection between the corporate community and the CFR has received further support from studies that have shown the centrality of the CFR within networks of top corporations and major non-profits, and in networks that focus exclusively on policy-discussion groups and think tanks (Eitzen, Jung & Purdy, 1982; Salzman and Domhoff, 1983; Burris, 1992, 2008). Direct links between the CFR and government have been demonstrated by studies of CFR members appointed to top government positions over many decades, up to and including the period covered in the present study – Reagan appointed 31 CFR members to his administration and Clinton appointed 32 to his (Burch, 1980; Domhoff, 1998, pp. 254–255, 2020, p. 479). These findings make it reasonable to infer that the CFR has served as a mechanism through which corporate interests are represented in government policymaking.

It follows, then, that inclusion of the policy preferences of the CFR within the framework developed by Gilens and Page might be expected to show that corporate preferences were even more predictive of policy outcomes than was shown by their original analysis. We thus adopt the dataset and the analytical method employed by Gilens and Page and seek to empirically support our argument by focusing on the subset of their dataset related to foreign policy issues. In addition to the actors considered by Gilens and Page, we add the policy preferences of one organization from the PPN – the CFR. Since the CFR is both a central and archetypal organization within the policy-planning network, it makes a good first test for the latter’s influence. We test whether (1) CFR preferences are indeed associated with policy outcomes and (2) whether adding them to the model proposed by Gilens and Page enhances the accuracy of predictions of political outcomes on foreign-policy issues.

Specifically, we hypothesize that, when entered in a regression model with more affluent citizens and business interest groups,

1 The preferences of the CFR significantly predict foreign policy outcomes; and.

2 The resulting model will be characterised by better overall fit and predictive accuracy than a model that does not include the CFR.

After assessing these hypotheses, we turn to a somewhat more detailed investigation of the outcomes in the dataset. We expect that the patterns identified in doing so can be plausibly interpreted as being consistent with our argument, while also shedding light on when CFR policy preferences did and did not prevail.

Data and methods

Much of our analysis adheres to that conducted by Gilens and Page (2014). From their original dataset (Gilens, 2015b) of 1779 public opinion survey questions covering a variety of policy areas across the 1981–2002 period, for which public survey data (including income level of respondents) existed and for which there was a clear outcome (whether or not a policy change occurred within a four-year window), we created a subset composed of the 295 questions in the larger dataset related to foreign policy, the largest of the policy areas in the original dataset. We used their estimates of the policy preferences of the ‘average citizen’ (those at the 50th income percentile) and the ‘economic elite’ (those at the 90th income percentile).Footnote 5 Both sets of preferences were on a continuous scale indicating the proportion supporting a policy change.

We also used their indexes of the positions of both business interest-groups and mass-based interest groups. Their measure of interest group policy preferences was constructed by starting from Baumgartner et al. (2009)‘s use of an index of 33 interest groups constructed by Baumgartner et al. (2009) from Fortune magazine’s “Power 25″ lists over a number of years. Baumgartner et al. found that the balance between the members of their list supporting and opposed to legislation correlated at 0.73 with a more comprehensive interest-group index. To this abbreviated list of 33 groups, Gilens and Page added groups from ten key industries reporting the highest lobbying expenditures. Their Interest Group Alignment indexes were created by coding the policy positions of each of these 43 groups on a four-point scale (strongly oppose, somewhat oppose, somewhat favour and strongly favour) and then counting the number of interest groups opposing and favouring policy change (where ‘somewhat’ positions were counted at half the value of ‘strongly’ positions). To adjust for the diminishing influence of additional groups on a given side for any given issue, they used the logarithms of the number of groups in support and opposition, using the below formula (Gilens, 2012, pp. 127–130; Gilens and Page, 2014, p. 569):

Net Interest-Group Alignment = ln(# Strongly Favour + [0.5 * # Somewhat Favour] + 1) – ln(# Strongly Oppose + [0.5 * # Somewhat Oppose] + 1)

The dependent variable in the analysis was whether or not the policy change proposed in the survey question was adopted within four years of the survey. Using multivariate analyses, Gilens and Page found that only the preferences of the “economic elites” and the interest groups (but not average citizens) were significantly associated with policy outcomes. In a secondary analysis, they divided the interest groups into 11 mass-based interested groups (e.g., ACLU, NRA), and 29 business interest groups (with three groups left uncategorized), finding that only the preferences of the business interest groups were significant predictors of policy outcomes. We use the same group variables in our analysis.

Finally, we created an additional independent variable, representing the policy preferences of the CFR. A difficulty here is that the CFR has always represented itself as non-partisan and it does not issue formal statements of policy preferences on behalf of the entire organization or all of its members. Indeed, few positions would be likely to represent its entire membership, particularly after its expansion from several hundred into the thousands in the 1970s in reaction to increased social pressures for diversity. We therefore sought out public statements of opinion from ‘senior figures’ associated with the CFR. We first assembled a list of ‘senior figures’ by examining publicly available CFR archival materials on their website and at their archives in Princeton University. These archives included information on directors, senior analysts, and members of study groups. Senior figures were defined as such based on their position within the CFR, length of tenure and professional background. Any CFR members or experts that lead study groups resulting in books published by the CFR or testified before Congress with CFR affiliation stated were also included, as such persons provide a good proxy of the position favoured by the leadership of the CFR.Footnote 6 In terms of professional background, any previous work in federal agencies was considered to be a particularly important indicator, as this type of overlapping (‘revolving door’) membership in government and a policy-discussion group is a characteristic feature of the PPN (Domhoff, 2022). Most of the ‘senior figures’ thus identified were directors, officers, expert employees, or the leaders of study groups that produced a published report.

We then coded the policy preferences of CFR ‘senior figures’ on the 295 foreign policy questions in the Gilens’ dataset on a four-point scale (0 = ‘Strongly Opposed’; 1 = ‘Somewhat Opposed’; 2 = ‘Somewhat Favour’; and 3 = ‘Strongly Favour’), following the steps below:

(1) We analysed the lectures, and other research, writing and educational projects available on the CFR website or in their archives at Princeton University that contained opinions authored or edited by one or more of the ‘senior figures’ on our list.

(2) We went through all volumes of Foreign Affairs, the CFR’s in-house journal, and identified all articles authored by ‘senior figures’ in the CFR. We coded all such articles for their policy position.

(3) We searched the Congressional archives for testimony by CFR personnel on the topics asked about in the survey questions used by Gilens and Page (for example, testimony on the efficacy of US foreign policy in Central America during the Reagan Administration).

(4) If the codes resulting from steps 1, 2 and 3 agreed, then we used the resulting code. If they did not agree or if they did not provide sufficient information to infer a CFR policy position, we turned to newspaper articles, speeches, and books by senior CFR figures, to resolve the disagreement.

Cases in which all available public documents from the CFR were unqualified in their opposition to or support for a policy were coded as ‘Strongly Opposed’ (‘0’) or ‘Strongly Favour’ (‘3’), respectively. In cases where the opinion seemed qualified, or where different CFR authors expressed different opinions, we made a judgment based on how the more ‘senior’ members of the CFR appeared to lean on the issue, and coded the preference as either ‘Somewhat Opposed’ (‘1’) or ‘Somewhat Favour’ (‘2’). In this way, we coded the CFR’s positions on all 295 survey questions from 1981 to 2002. Some CFR positions were coded based on preferences expressed prior to the survey question being asked. Many foreign policy issues remain salient over a number of years, and in many cases ‘senior figures’ associated with the CFR had presented clearly articulated positions on the issues before they became prominent in public debate.

In order to assess the relative predictive power of the preferences of economic elites, mass-based and business interest groups and the CFR, we first examined the bivariate correlations between the above variables, then followed with bivariate logistic regression models, and finally determined the best-fitting multivariate logistic regression model. For these analyses, we transformed the preferences of citizens at the 50th and 90th percentiles from proportions to percentages, to facilitate interpretation of the odds ratios from the logistic regressions. We calculated the interest group index variables in the same way as in the original study. The four-point CFR scale was treated as continuous to generate Pearson Correlations, but as categorical for the logistic regression analyses. We used policy outcomes (re-coded as a binary variable, with no policy change coded as ‘0’ and all changes coded as ‘1’ – replacing the original indicator of the time period in which the change occurred) as the dependent variable. The analyses were performed using R (R Core Team, 2021). The coded positions of the CFR on the 295 foreign policy questions in the Gilens dataset are available as a supplementary file.

Results

The bivariate Pearson correlations for our subset of 295 foreign policy questions (Table 2), show an interesting pattern of similarities and differences with those in Gilens and Page’s full set of 1779 questions.Footnote 7 As in their findings, we found no statistically significant correlations between the preferences of the economic elites and the preferences of the interest groups, nor with the preferences of the CFR. The preferences of business interest groups on our subset of foreign policy questions, however, showed a significant negative correlation with those of mass public interest groups, as well as a significant positive correlation with the preferences of the CFR.

When bivariate logistic regression models were performed with policy outcomes as the dependent variable, there were significant, positive relationships between the preferences of economic elites (OR = 1.034, 95% CI = 1.019 to 1.048) and business interest groups (OR = 1.706, 95% CI = 1.244 to 2.338) and policy outcomes. The CFR was entered as a categorical variable with four levels. Using the lowest level (‘strongly oppose’) as the reference category, the odds ratios at the second level (OR = 2.931, 95% CI = 1.366 to 6.285), third level (OR = 4.659, 95% CI = 2.143 to 10.129) and fourth level (OR = 11.722, 95% CI = 5.940 to 23.133) were all positive and significant. There was a significant negative relationship between the preferences of mass-based interest groups and policy outcomes (OR = .428, 95% CI = .268 to .685). Table 3 summarizes the significance, fit and accuracy of these bivariate models.

We next ran a series of multivariate logistic regression analyses, with results for the best fitting model shown in Table 4. These results show that when economic elites, mass-based interest groups, business interest groups and the CFR are included in the same model, only the preferences of the economic elites and the CFR remain significant. From the odds ratios, we can see that for every 1% increase in support from the economic elites, the odds of a policy change increase by about 1.04 times. Turning to the odds ratios for the different levels of CFR preferences, we can see that the shift from ‘strongly opposes’ to ‘somewhat opposes’ is associated with an increase of 3.25 times in the odds of a policy change. The difference between ‘somewhat opposes’ and ‘somewhat favours’ is relatively small, while the difference between the latter and ‘strongly favours’ is dramatic: the odds of policy change associated with the highest level of CFR support are 13.8 times higher than the reference level (‘strongly opposes’). Though not statistically significant, we note that the coefficients for the mass-based interest groups and business interest groups variables are negative - support for a policy from both sets of groups is associated with lower odds of a policy change.

The strong correlation between the preferences of average citizens and economic elites created a multicollinearity issue preventing us from including both in our multivariate regression models; we thus included them separately in different models. We found essentially no difference in the results, aside from a slight augmentation of CFR influence when ‘average citizens’ replace ‘economic elites.’ Finally, as a robustness check, we repeated the regression analysis with the CFR preference variable collapsed from a four-point scale to a binary scale (‘favor’ vs. ‘oppose’) and found the same general pattern of results.Footnote 8

Table 5 summarizes the other models that were evaluated. Of particular interest is a comparison of the model discussed above (shown in Table 4) and Model 2 in Table 5, which is closest to the final model selected by Gilens and Page in their analysis. Our model, which includes the CFR, results in better fit and greater predictive accuracy than does the model that includes only the economic elites, mass-based interest groups and business interest groups.

Thus, the key questions of this study can be answered in the affirmative: the preferences of the CFR do significantly predict foreign policy outcomes during this period and a multivariate model that includes the CFR demonstrates better fit and predictive accuracy than models which do not.

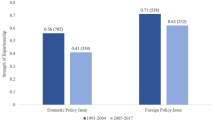

As a final step, we briefly contrasted preferences and outcomes for the CFR with those for citizens at the 90th percentile, our proxy for the ‘economic elite’ (hereafter, ‘EE’), since only these two sets of preferences were found to significantly predict policy outcomes. For the present dataset of foreign policy questions across the 1981–2002 period, if we transform preferences into binary categories, we find that the CFR and economic elites shared the same policy preferences 52.5% of the time and, their shared preferences prevailed on 79.4% of the issues and failed to prevail on 20.8%. They disagreed 47.5% of the time, and when they disagreed CFR preferences prevailed 60.7% of the time and those of the EE prevailed 39.3% of the time. Altogether, then, the preferences of the CFR prevailed in 70.5% of cases.

We divided the foreign policy questions into seven broad issue areas, using the full text of the survey questions (kindly provided by M. Gilens). Table 6 presents these issue areas, ranked by how often CFR preferences prevailed. As can be seen, the frequency with which CFR preferences prevailed ranged from a high of 82.6% on trade-related issues to a low of 59.5% on issues related to Central America. The CFR, as it has since WWII, took strongly ‘free trade’ positions on trade and aggressively anti-communist positions in Central America. What explains this difference in the degree to which the policies it supported were implemented?

A comparison of the coalitions that emerged around the two sets of issues suggests that the overall balance of forces appears to have been more favourable for the CFR positions on the trade-related issues. Although the preferences of the business interest groups were no longer statistically significant once those of the CFR were included in our regression model, the fact remains that these business groups were highly engaged in the political battles around trade (with stated preferences on 22.1% of possible opportunities, considerably higher than their overall average of less than 5% for all foreign policy issues) and their active involvement may have been critical. In sharp contrast, on the 42 questions related to Central America, primarily involving US efforts directed against the FMLN in El Salvador and the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, the policies supported by the CFR received little support from either ‘average citizens’ or ‘economic elites’ and neither the business nor the mass-based interest groups were highly engaged. Nonetheless, despite this lack of interest group alliances, the CFR’s preferences still prevailed on 59.5% of the issues. Thus, the corporate-friendly worldview advocated for by the CFR prevailed in nearly 60% of the cases in which it had little additional support from the corporate community and in about 85% of cases in which the business community was actively mobilized on the same side as the CFR.

Discussion and conclusion

Our article has extended Gilens and Page’s important work on the political influence of business groups and affluent citizens (‘economic elites’) in US politics in one issue area by adding the policy preferences of senior figures of the Council on Foreign Relations, a leading foreign policy discussion group. We first reviewed research showing the connections between the corporate community and the CFR, as well as between the CFR and the government – including research on CFR members who were part of presidential administrations during the 1981–2002 period. Next, through multivariate logistic regression analysis, we found that the policy preferences of the CFR, both alone and along with those of economic elites, significantly predicted foreign policy outcomes. In the best-fitting multivariate model, none of the original interest group predictors remained significant. Our findings support the assertion that economic elites and the organised corporate community are disproportionately successful in these struggles. These findings are consistent with results from a different set of survey studies concerning foreign-policy issues over a 30-year period (Jacobs & Page, 2005). As summarized by Gilens (2012, p. 43), these researchers concluded that “business leaders and experts have the greatest ability to sway foreign policy, but that the public as a whole has little or no influence.” The findings also provide quantitative support for previous claims about the importance of the CFR based on the analysis of archival research (Domhoff, 2020, Ch. 14). Taken together with these earlier findings, our results suggest that a model of biased pluralism that includes the policy planning network offers a more complete specification of the mechanisms through which corporate influence takes place.

More broadly, we believe that our inclusion of the policy-planning network provides a fuller model of the mechanisms through which corporate influence is deployed. Corporate-backed organizations in the policy planning network seek to articulate the long-term general interests of the US corporate community across a wide array of issues. In this, they contrast sharply with business ‘special-interest’ groups, which are engaged only on issues perceived as bearing directly on their operations. In the sample of 295 issues for the 1980–2002 period studied here, senior figures from the CFR had stated preferences on all 295 issues in the dataset, while the average business interest group took a policy stance on only 4.9% of these foreign policy issues.

Nonetheless, as we have seen, CFR preferences did not always prevail. As noted above, the corporate dominance perspective holds that corporations came to dominate US politics through political struggles involving shifting alliances of major political actors. Consistent with this position, based on our limited exploration of the policy areas in which the CFR’s preferences were more or less likely to prevail, we suggested that the answer likely lies in the balance of power that emerged on different issues. Policy proposals are put forward in a context of competition and conflict between different organized power actors (the corporate community with its moderate conservative and ultraconservative wings, liberal and labor groups, etc.), all of whom need to take public opinion into account at least every two years when elections are held. This study and many others suggest that the corporate community prevails more often than not, but it does not prevail in all cases.

As an example, we return to the issue of expanding international trade, always central to the CFR’s vision and the area on which the organization’s preferences were most likely to prevail during our period. We suggest that the ultimate success of these policy initiatives was the result of a relatively united corporate community after the Trade Act of 1974 was passed. These policies were supported not only by the moderate conservatives in the corporate community who were typically aligned with the CFR, but also by most of the corporate ultraconservatives from the mid-1980s on, represented by organizations such as the Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers and the American Farm Bureau Federation. These victories contrast sharply with the slow progress of the CFR’s trade agenda in the 1950s and much of the 1960s, when ultraconservatives opposed the widening of free trade, while unions, during this period of economic expansion, were more favourable to it. By the 1980s, this pattern had reversed: as corporations turned overseas to reduce labor costs, they supported trade liberalization while unions turned to opposition (Domhoff, 2020). In the face of opposition from labor and tepid public support, this coalition funded and organised efforts to shape public opinion across the country, with particular focus on key congressional districts. Provisions and side agreements designed to appeal to environmentalists and unions were added to further blunt opposition, which led to support by the large national environmental groups (although not from the unions). In the end, this all-out corporate-sponsored campaign, aimed at both elected officials and the public, was successful, offering a clear illustration of corporate triumph in the face of opposition (Dreiling and Darves, 2016; Mayer, 1998). In the highly consequential battles over trade during the 1982–2002 period, a united corporate community prevailed.Footnote 9

Central America represents a contrasting case in which the CFR view, although, in fact, largely triumphant in the end, faced stiff opposition from liberals and an anti-war movement, and without broad support from business groups (Smith, 2000). With Democrats controlling the House during Reagan’s first term and both the House and the Senate from 1987 on, and with little active engagement on the part of the business community, the aggressively interventionist policies favoured by the CFR faced a number of setbacks. Further research into these and similar political struggles promises to offer a better understanding of the limits of the influence of the policy-planning network and a more nuanced understanding of the role of variations in the balance of political forces across different issues.

An additional avenue for future research would involve the investigation of the influence of policy-planning groups focused on domestic policy, such as the Business Roundtable. We note that results might differ for domestic policy, as both mass and business interest groups appear to have been more engaged on domestic issues. Whereas the 11 mass interest groups in the dataset took stances on 6.1% of foreign policy issues, they did so on 10.3% of the remaining 1484 issues in the dataset. Likewise, business interest groups took a stance on only 4.9% of foreign policy issues compared to 10.4% of domestic issues. It is possible that the relative lack of engagement of interest groups on foreign policy issues helps account for the positive findings for the CFR in this article. This is an important topic for future research and one which could be further explored using the Gilens dataset along with other available material.

In this article, we have used the case of the Council on Foreign Relations as an illustration of how policy-planning networks may serve as a mechanism of corporate influence on the policy-making process. After reviewing the origins of the CFR and its ascent to a position of influence during World War II, we argued that it played an influential role during the postwar decades, and reviewed research showing the connections between the corporate community, the CFR and government policymaking. We then used logistic regression to show that the CFR’s policy positions more accurately predicted policy outcomes than did those of the business interest groups that are often the focus of attention in research on corporate influence. While much work remains to be done to establish the connection between corporate interests and US policy, we believe that we have shown that the policy-planning network, exemplified by organizations such as the CFR, should be part of the investigation when these questions are explored.

Availability of data and material

All data is available: a reference and URL is provided for a publicly available dataset used in this study, and new data used in this study is provided in a supplementary file.

Code availability

The R software code used in this study is provided as a supplementary file.

Notes

The few wealthy liberal members, or one-time members, of the corporate leadership, although often discussed and lionised in the media, are atypical and do not speak for any corporate group, as shown in a book comparing their visible efforts with the ‘stealth politics’ of ultraconservative billionaires (Page, Seawright and Lacombe, 2019).

Although their empirical focus was on special-interest groups, the policy-planning process has also been discussed by Page and Gilens as one of the mechanisms through which the wealthy transform their economic power into political power (Page and Gilens, 2017). Policy-planning and special-interest networks are complemented by ‘candidate selection’ – primarily large donations to political candidates and ‘opinion shaping’ - attempts to shape public opinion. Although efforts to shape the opinions of the general public have generally failed to demonstrate long term results (Page and Bouton, 2008; Page and Jacobs, 2009), they may help foster doubt, delay, or a sense of crisis in the context of efforts to have specific legislation enacted (Michaels, 2008; Oreskes and Conway, 2011).

Thus, the CFR from the start was different from a think tank. In any event, only one or two small think tanks had been created by the early 1920s, when the CFR was founded. Thus, political scientists who study think tanks either do not include the CFR within their purview (e.g., Rich, 2004), or call it a ‘policy research institution’ (Abelson, 1996), or a ‘hybrid organization’ (McGann, 2007, p. 93). A sociologist who interviewed members of think tanks about their perspectives called the CFR a conservative ‘activist-expert organization’ (Medvetz, 2012, pp. 92–94, 114).

The CFR played a similarly critical role in the reshaping of foreign policy in the early 1970s, beginning with its creation of an organization, the Trilateral Commission, that included CFR counterparts in Western Europe and Japan; this work came to fruition during the Carter Administration, in which ‘at least fifty-four members of the CFR’ directly served (Abelson, 1996; Shoup, 1980; Sklar, 1980).

Of course, citizens at the 90th income percentile are, as Gilens and Page point out, “neither very rich nor very elite”; nonetheless, they argue that “To the extent that their policy preferences differ from those of average-income citizens…there are likely to be similar but bigger differences between average-income citizens and the truly wealthy” (pp. 568–569). See also Gilens, 2012, pp. 2–3.

To offer examples, we included as ‘senior figures’ the heads of research groups that eventually produced published reports, such as John C. Whitehead, co-author of Lessons of the Mexican Peso Crisis (Whitehead and Kravis, 1997), and Bernard W. Aronson and William D. Rogers, who co-authored U.S. – Cuban Relations in the twenty-first Century: A Follow-On Report (Rogers and Aronson, 2001). They authored the introductions to these reports and were undoubtedly the guiding force in their publication. All three, although never having served as CFR directors, were nonetheless called upon on several occasions to develop reports and deliver testimony on issues pertaining to Latin America. At the time Whitehead wrote his CFR book in 1997, he was the retired co-chair of Goldman, Sachs, an investment banking firm, where he had worked for 38 years, and served on the board of trustees of a large foundation and a major think tank. When Aronson and Rogers co-authored their book, Aronson was the chair of an international investment firm he had co-founded after serving in various roles in the state department in the Carter, Reagan, and Clinton administrations. Rogers, a corporate lawyer for most of his career, was a founding member of Kissinger Associations, an international consulting firm.

Gilens and Page sought to correct for correlated measurement error between their independent variables. They report the resulting adjusted correlations and use structural equation modelling in their regression analyses in order to include these adjustments (see “Testing Theories of American Politics,” Appendix). Their approach has been discussed and criticized elsewhere (e.g., Enns, 2015a). Here we report unadjusted correlations.

Given the difficulties discussed in the Methods section related to attempting to attribute policy preferences to an organization such as the CFR, we acknowledge the possibility that replication with different raters or findings of future archival research might result in a revision to some of our coded results for CFR policy preferences. We feel that changes from ‘strongly’ to ‘somewhat’ or vice-versa were more likely than complete reversals (from ‘support’ to ‘oppose’, or vice-versa), given that CFR-affiliated authors typically had reasonably consistent positions on broad policy issues. Thus, as a robustness check, we collapsed the four-point rating scale to a less precise binary scale, with only ‘support’ and ‘oppose’ as values and re-ran our analyses. The results remain essentially the same: the coefficients for the mass-based and business interest groups remain negative but non-significant, while the preferences of citizens at the 90th income percentile and of the CFR are statistically significant positive predictors of policy outcomes. The odds of policy change based on policy ideas supported by the CFR are 4.9 times higher than the odds associated with CFR opposition.

Although beyond the scope of this article, these results on trade raise a number of further questions on the relationship between political inequality and other types of inequality. Recent research has demonstrated that the trade deals discussed here have contributed to patterns of regional job loss and subsequently greater levels of economic inequality (Autor, Dorn & Hanson, 2013, 2016; Owen and Johnston, 2017; Pierce and Schott, 2016). These trends, in turn, have been associated with broader indicators of social or health-related inequality: higher levels of incarceration, poorer health outcomes and higher levels of mortality from drug use disorders (Dean and Kimmel, 2019; Nosrati et al., 2019). Indeed, the geographical pattern of job losses has also been associated with increasing levels of political partisanship and may partially explain the outcome of the 2016 presidential election (Autor et al., 2020).

References

Abelson, D. (1996). American think-tanks and their role in U.S. foreign policy. New York: St. Martin’s press.

Alpert, I., & Markusen, A. (1980). The professional production of policy, ideology, and plans: Brookings and Resources for the Future. Critical Sociology, 9(2–3), 94–106.

Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2013). The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States. The American Economic Review, 103(6), 2121–2168 https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2121

Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2016). The China shock: Learning from labor-market adjustment to large changes in trade. Annual Review of Economics, 8, 205–240 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080315-015041

Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., Hanson, G., & Majlesi, K. (2020). Importing political polarization? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure. American Economic Review, 110(10), 3139–3183.

Baumgartner, F. R., Berry J. M., Hojnacki, M., Leech, B. L., & Kimball, D. C. (2009). Lobbying and policy change: Who wins, who loses, and why. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berry, J. M. (1997). The interest group society. 3rd ed. New York: Longman.

Bonds, E. (2016). Beyond Denialism: Think tank approaches to climate change. Sociology Compass, 10(4), 306–317.

Branham, A. J., Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2017). When do the rich win? Political Science Quarterly, 132(1), 43–62.

Burch, P. (1980). Elites in American history: The new deal to the Carter Administration (Vol. 3). New York: Holmes & Meier.

Burris, V. (1992). Elite policy-planning networks in the United States. Research in Politics and Society, 4, 111–134.

Burris, V. (2008). The interlock structure of the policy-planning network and the right turn in US state policy. Research in Political Sociology, 17, 3–42.

Council on Foreign Relations [CFR]. (1947). The council on foreign relations: A record of twenty-five years, 1921–1946. New York: Council on Foreign Relations.

Dean, A., & Kimmel, S. (2019). Free trade and opioid overdose death in the United States. SSM - Population Health, 8(April), 100409.

Domhoff, G. W. (1998). Who rules America? Power and politics in the year 2000. 3rd ed. Mountain View: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Domhoff, G. W. (2020). The corporate rich and the power elite in the twentieth century. New York: Routledge.

Domhoff, G. W. (2022). Who rules America? The corporate rich, white nationalist Republicans, and inclusionary Democrats in the 2020s. 8th ed. New York: Routledge.

Downey, L., & Susan, S. (2010). Inequality, democracy, and the environment. Organization and Environment, 23(2), 155–188.

Dreiling, M. C., & Darves, D. Y. (2016). Agents of neoliberal globalization: Corporate networks, state structures, and trade policy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Eitzen, S. D., Jung, M. A., & Purdy, D. A. (1982). Organizational linkages among the inner group of the capitalist class. Sociological Focus, 15(3), 179–189.

Enns, P. K. (2015a). Relative policy support and coincidental representation. Perspectives on Politics, 13(4), 1053–1064.

Enns, P. K. (2015b). Reconsidering the middle: A reply to Martin Gilens. Perspectives on Politics, 13(4), 1072–1074.

Gilens, M. (2012). Affluence and influence: Economic inequality and political power in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gilens, M. (2015). Economic inequality and political representation [dataset]. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Retrieved January 20, 2020 (https://www.russellsage.org/economic-inequality-and-political-representation).

Gilens, M., & Page, B. I. (2014). Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), 564–581.

Gilens, M., & Page, B. I. (2016). Critics argued with our analysis of US political inequality. Here are 5 ways they’re wrong. The Washington Post, May, 23, 1–5.

Gonzalez, G. A. (2001). Corporate power and the environment: The political economy of US environmental policy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Gramer, R. (1995). The German question from recovery to rearmament: The Council on Foreign Relations and its voices of dissent, 1942–1950. In paper presented at the Society for Historians of American foreign relations. Annapolis.

Gramer, R. (1997). Reconstructing Germany, 1938–1949: United States foreign policy and the cartel question. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University.

Grose, P. (1996). Continuing the inquiry: The council on foreign relations from 1921 to 1996. New York: Council on Foreign Relations.

Helleiner, E. (2014). Forgotten foundations of Bretton Woods: International development and the making of the postwar order. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Hogan, M. (1987). The Marshall Plan: America, Britain, and the reconstruction of Western Europe, 1947–1952. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobs, L., & Page, B. (2005). Who influences U.S. foreign policy? American Political Science Review, 99, 107–123.

Mayer, F. (1998). Interpreting NAFTA: The science and art of political analysis. New York: Columbia University Press.

McConnell, G. (1970). Private power & American democracy. New York: Vintage.

McGann, J. (2007). Think tanks and policy advice in the United States: Academics, advisors and advocates. New York: Routledge.

Medvetz, T. (2012). Think tanks in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McLellan, D. S., & Woodhouse, C. E. (1960). The business elite and foreign policy. Political Research Quarterly, 13(1), 172–190.

Michaels, D. (2008). Doubt is their product: How industry’s assault on science threatens your health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mintz, B. (2017). Who rules America? and the policy-formation network: The case of venture philanthropy. Pp. 126–35 in Studying the Power Elite: Fifty years of Who Rules America? New York: Routledge.

Murray, J. (2017). Interlock globally, act domestically: Corporate political unity in the 21st century. American Journal of Sociology, 122(6), 1617–1663.

Nosrati, E., Kang-Brown, J., Ash, M., McKee, M., Marmot, M., & King, L. P. (2019). Economic decline, incarceration, and mortality from drug use disorders in the USA between 1983 and 2014: An observational analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 4(7), e326–e333.

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2011). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Owen, E., & Johnston, N. (2017). Occupation and the political economy of trade: Job routineness, offshorability and protectionist sentiment. International Organization, 71(4), 665–699 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818317000339

Page, B. I., & Bouton, M. B. (2008). The foreign policy disconnect: What Americans want from our leaders but don’t get. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Page, B. I., & Gilens, M. (2017). Democracy in America?: What has gone wrong and what we can do about it. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Page, B. I., & Jacobs, L. R. (2009). Class war?: What Americans really think about economic inequality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Page, B. I., Seawright, J., & Lacombe, M. J. (2019). Billionaires and stealth politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Peschek, J. G. (1987). Policy-planning organizations: Elite agendas and America’s rightward turn. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Peschek, J. G. (2017). The policy-planning network, class dominance, and the challenge to political science. Pp. 115–25 in Studying the Power Elite: Fifty years of Who Rules America?. Routledge.

Pierce, J. R., & Schott, P. K. (2016). The surprisingly swift decline of US manufacturing employment. The American Economic Review, 106(7), 1632–1662 https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20131578

Poulantzas, N. (1973). Political power and social classes. London: New Left Books.

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for statistical computing, , Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

Rich, A. (2004). Think tanks, public policy, and the politics of expertise. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rogers, W. D., & Aronson, B. W. (2001). US-Cuban relations in the 21st century: A follow-on report: report of an independent task force sponsored by the council on foreign relations. Washington, D.C.: Council on Foreign Relations.

Roy, W. (1999). Socializing capital: The rise of the large industrial corporation in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Salzman, H., & Domhoff, G. W. (1983). Nonprofit organizations and the corporate community. Social Science History, 7(2), 205–216.

Schlozman, K. L., & Tierney, J. T. (1986). Organized interests and American democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Schlozman, K. L., Verba, S., & Brady, H. E. (2012). The unheavenly chorus: Unequal political voice and the broken promise of American democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schulzinger, R. D. (1984). The wise men of foreign affairs: The history of the council on foreign relations. New York: Columbia University Press.

Shoup, L. H. (1975). Shaping the postwar world: The Council of Foreign Relations and United States war aims during World War II. Insurgent Sociologist, 5(3), 7–52.

Shoup, L. H. (1980). The Carter presidency, and beyond: Power and politics in the 1980s. Palo Alto, CA: Ramparts Press.

Sklar, H., ed. (1980). Trilateralism: The trilateral commission and elite planning for world management. Boston: South End Press.

Skocpol, T. (2007). Government activism and the reorganization of American civic democracy. Pp. 39–67 in The transformation of American politics: Activist government and the rise of conservatism, edited by P. Pierson and T. Skocpol. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University press.

Smith, M. A. (2000). American business and political power: Public opinion, elections, and democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Steil, B. (2013). The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the making of a new world order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Van Apeldoorn, B., & De Graaff, N. (2016). American grand strategy and corporate elite networks: The open door since the end of the cold war. New York: Routledge.

Wala, M. (1994). The council on foreign relations and American foreign policy in the early cold war. Providence, RI: Berghahn Books.

Whitehead, J. C., & Kravis, M. J. (1997). Lessons of the Mexican Peso Crisis. Washington, D.C.: Council on Foreign Relations of the United States of America.

Whitham, C. (2016). Post-war business planners in the United States, 1939–48: The rise of the corporate moderates. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Woodhouse, C. E., & McLellan, D. S. (1966). American business leaders and foreign policy: A study in perspectives. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 25(3), 267–280.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Martin Gilens, both for making his original dataset publicly available and for sharing the original text for the survey questions used in this study. We would also like to thank Professors Mark Haggard and Bruno Di Giusto for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Mistakes remain our own.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts or competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luther-Davies, P., Doniec, K.J., Lavallee, J.P. et al. Corporate political power and US foreign policy, 1981–2002: the role of the policy-planning network. Theor Soc 51, 629–652 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-022-09475-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-022-09475-3