Abstract

This article presents a reevaluation of C. Wright Mills’s classic book, The Power Elite, in light of recent historical evidence about the changing nature of the corporate elite in the United States. I argue that Mills’s critique of the mid-twentieth century American elite, although trenchant and in large part appropriate, fails to acknowledge the extent to which business leaders of that era adopted a moderate and pragmatic approach to politics. Operating with an orientation they termed “enlightened self-interest,” the elites of that era promoted policies that—at least to an extent—served the interests of the larger population. I show how the history of the American corporate elite as well as the character of the current US big business community allows us to gain a clearer perspective on the actions of the group’s mid-century counterparts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is, not surprisingly, a huge literature on Mills and The Power Elite, some of which I discuss below. See Geary (2009, pp. 152–168) for a detailed and sensitive recent treatment by a historian, and http://www.newleftproject.org/index.php/site/series/the_power_elite_revisited for a series of brief essays on the book by leading British sociologists. See Adler (2009) for an excellent discussion of the value of rereading classic works in sociology.

For illustrations of work that Mills saw as reflective of these views, see, among others, Bell (1960), Dahrendorf (1959), Galbraith (1952), and Riesman (1950). As I have argued elsewhere (Mizruchi and Hirschman 2009), these works were considerably more subtle, and less celebratory, than Mills suggested.

See, for example, Mills’s biting discussions of what he called “grand theory” and “abstracted empiricism” in his 1959 book, The Sociological Imagination. Although the criticism of “grand theory” was directed primarily at Talcott Parsons, who was at Harvard, the attack on “abstracted empiricism” appears to have been directed at Mills’s Columbia colleague Paul Lazarsfeld. The latter is a point on which two very different biographers of Mills—Horowitz (1983, pp. 95–99) and Geary (2009, pp. 170–173)—agree.

Mills (1956, p. 18) defined the power elite as “those political, economic, and military circles which as an intricate set of overlapping cliques share decisions having at least national consequences.”

Several of the most well-known critiques of Mills, including those by Dahl, Bell, Adolf A. Berle, Jr., William Kornhauser, Talcott Parsons, Paul M. Sweezy, and Dennis H. Wrong—all cited in this article—were compiled into a book edited by Domhoff and Ballard (1968). Here I cite all these articles, with page numbers where necessary, as they appeared in the Domhoff and Ballard volume, with a 1968 date. Most of them originally appeared in the years immediately following the publication of The Power Elite.

As Mills put it (1956, p. 280), “We cannot infer the direction of policy merely from the social origins and careers of the policy-makers … not all men who effectively represent the interests of a stratum need in any way belong to it or personally benefit by policies that further its interests.”

The idea that a high level of military spending was necessary to maintain the economy in the postwar period was a widely-shared view among critics of American capitalism. For a classic example of this view, see Baran and Sweezy (1966).

See Phillips-Fein (2009) for a detailed treatment of efforts by American business to roll back the policies of the New Deal.

The US Chamber of Commerce adopted a more moderate approach for a brief period during the 1940s under the leadership of Eric Johnston. Johnston was eventually pushed out of his position in 1946 under pressure from local branches of the Chamber, who found his policies overly liberal. See Mizruchi (2013, pp. 53–56) for a discussion of Johnston’s tenure.

Mills analyzed the group to which he referred as the power elite, which consisted of leading members of the business, political, and military communities. In my historical discussion here (see Mizruchi 2013 for a more detailed presentation), I refer primarily to a group I call the “corporate elite,” which consisted (and consists) of the heads of the largest American companies. Although Mills indicated that the three groups in his triumvirate held relatively equal levels of power, it is possible to interpret his analysis as giving priority to business (see, for example, Sweezy 1968), an interpretation that I share. Although I also considered the role of political elites in my study, my focus was on the corporate elite, which I saw as both influencing and influenced by the state. Given the importance of corporate leaders in both Mills’s analysis and mine, a discussion focusing on these business officials is relevant to an assessment of Mills’s argument.

Ralf Dahrendorf (1959, pp. 41–47), for example, argued that the diffusion of stock ownership across the general populations of developed market societies indicated that these societies had transcended capitalism altogether. The suggestion, based on Berle and Means’s classic book (1968 [1932]), that the control of corporations had passed to hired managers, indicated, according to Dahrendorf, that ownership of capital was no longer a relevant variable in contemporary societies. See Mizruchi and Hirschman (2009, especially pp. 1083–1096).

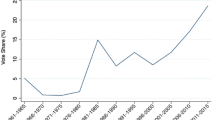

See Keith Poole’s website, http://voteview.com/, for systematic evidence of this increased polarization over time, virtually all of which is accounted for by the increasing conservatism of Congressional Republicans.

Funding for the bank was eventually restored, but widespread opposition continues to exist.

Mills argued, of course, that Congress was an element of the middle levels of power and thus was not where the “big decisions” were made. Questions could be raised about this point even in Mills’s time. Virtually every important domestic issue of the postwar period was at one time or another debated in Congress, a point that Mills, with his focus on foreign policy, neglected to mention. At the same time, Mills was likely correct that power in the US government had, at the time he was writing, moved increasingly to the executive branch. One could argue that in the contemporary United States, the legislative branch has reasserted its power. This was certainly the case during the Obama presidency, in which virtually every initiative the president proposed after the Republicans gained control of the House in the 2010 elections was thwarted. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the centralization of power in the US government is related to the degree of unity within the elite. If, as I have argued, the contemporary American corporate elite is fragmented relative to the elite of the postwar period, it would follow that the locus of state power could have shifted from the executive branch to the Congress.

A recent study by Chu and Davis (2016b) demonstrates that between 1997 and 2010, the density of the network of director interlocks among American firms was reduced by more than 30%. The average number of ties among the Standard & Poor’s 1500 leading US firms declined from 7.14 in 2000 to 4.98 in 2010. The average distance between firms increased from 3.21 in 2000 to 4.23 in 2010. In 2000 there were 62 firms in the network with more than 20 interlocks. By 2010 there was only one such firm.

References

Adler, P. S. (2009). Introduction: A social science which forgets its founders is lost. In Adler (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of sociology and organization studies (pp. 3–19). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bachrach, P., & Baratz, M. S. (1962). Two faces of power. American Political Science Review, 56, 947–952.

Baran, P. A., & Sweezy, P. M. (1966). Monopoly capital: An essay on the American economic and social order. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Barton, A. H. (1985). Determinants of economic attitudes in the American business elite. American Journal of Sociology, 91, 54–87.

Bell, D. (1960). The end of ideology: On the exhaustion of political ideas in the fifties. New York: Collier.

Bell, D. (1968). The Power Elite reconsidered. In G. W. Domhoff & H. B. Ballard (Eds.), C. Wright Mills and The Power Elite (pp. 189–225). Boston: Beacon Press.

Berle Jr., A. A. (1968). Are the blind leading the blind? In G. W. Domhoff & H. B. Ballard (Eds.), C. Wright Mills and the power elite (pp. 95–99). Boston: Beacon Press.

Berle Jr., A. A., & Means, G. C. (1968 [1932]). The modern corporation and private property (Revised ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Calmes, J. (2013). For ‘party of business,’ allegiances are shifting. New York Times, January 15, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/16/us/politics/a-shift-for-gop-as-party-of-business.html?_r=0.

Chu, J., & Davis, J. (2016a). Corporate America’s old boys’ club is dead—And that’s why big business couldn’t stop trump. The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/corporate-americas-old-boys-club-is-dead-and-thats-why-big-business-couldnt-stop-trump-67035.

Chu, J. S. G., & Davis, G. F. (2016b). Who killed the inner circle? The end of the era of the corporate interlock network. American Journal of Sociology, 122, 714–754.

Dahl, R. A. (1968). A critique of the ruling elite model. In G. W. Domhoff & H. B. Ballard (Eds.), C. Wright Mills and the power elite (pp. 25–36). Boston: Beacon Press.

Dahrendorf, R. (1959). Class and class conflict in industrial society. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

David, T., & Westerhuis, G. (Eds.). (2014). The power of corporate networks: A comparative and historical perspective. New York: Routledge.

Davis, A. (2012). The shifting contours of elite power. New Left Project. http://www.newleftproject.org/index.php/site/article_comments/the_shifting_contours_of_elite_power.

Davis, A. (2014). Embedding and disembedding of political elites: a filter system approach. The Sociological Review. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12186.

Davis, G. F. (2009). Managed by the markets: How finance re-shaped America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davis, G. F., & Mizruchi, M. S. (1999). The money center cannot hold: commercial banks in the U.S. system of corporate governance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 215–239.

Dobbin, F., & Zorn, D. (2005). Corporate malfeasance and the myth of shareholder value. Political Power and Social Theory, 17, 179–198.

Domhoff, G. W. (1970). The higher circles: The governing class in America. New York: Vintage.

Domhoff, G. W. (1979). The powers that be: Processes of ruling class domination in America. New York: Vintage.

Domhoff, G. W. (2013). The myth of liberal ascendancy: Corporate dominance from the great depression to the great recession. Boulder: Paradigm.

Domhoff, G. W., & Ballard, H. B. (Eds.). (1968). C. Wright Mills and the power elite. Boston: Beacon Press.

Dreiling, M. (2001). Solidarity and contention: The politics of security and sustainability in the NAFTA conflict. New York: Garland.

Drutman, L. J. (2015). The business of America is lobbying. New York: Oxford University Press.

Galbraith, J. K. (1952). American capitalism: The concept of countervailing power. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Geary, D. (2009). Radical ambition: C. Wright Mills, the left, and American social thought. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goodman, P. (1960). Growing up absurd: Problems of youth in the organized society. New York: Vintage.

Horowitz, I. L. (1983). C. Wright Mills: An American utopian. New York: Free Press.

Kogut, B. (Ed.). (2012). The small worlds of corporate governance. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kornhauser, W. (1968). ‘power elite’ or ‘veto groups’? In G. W. Domhoff & H. B. Ballard (Eds.), C. Wright Mills and the power elite (pp. 37–59). Boston: Beacon Press.

Lipset, S. M. (1962). Introduction. In R. Michels, Political parties (pp. 15–39). New York: Free Press.

Mills, C. W. (1948). The new men of power: America’s labor leaders. New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World.

Mills, C. W. (1951). White collar: The American middle classes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mills, C. W. (1956). The power elite. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mizruchi, M. S. (1992). The structure of corporate political action: Interfirm relations and their consequences. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mizruchi, M. S. (2013). The fracturing of the American corporate elite. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mizruchi, M. S., & Hirschman, D. (2009). The Modern Corporation as social construction. Seattle Law Review, 33, 1065–1108.

Newmyer, T. (2015). The inside story of how big business lost Washington. Fortune, February 20. http://fortune.com/2015/02/20/the-inside-story-of-how-big-business-lost-washington/.

Packard, V. (1957). The Hidden Persuaders. New York: Pocket Books.

Parsons, T. (1968). The distribution of power in American society. In G. W. Domhoff & H. B. Ballard (Eds.), C. Wright Mills and the power elite (pp. 60–88). Boston: Beacon Press.

Pearlstein, S. (2016). How big business lost Washington. Washington Post Wonkblog, September 2, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/09/02/how-big-business-lost-washington/.

Phillips-Fein, K. (2009). Invisible hands: The businessmen’s crusade against the New Deal. New York: Norton.

Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2003). Income inequality in the United States, 1913-1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1–39.

Riesman, D. (1950). The lonely crowd: A study of the changing American character. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Schriftgiesser, K. (1960). Business comes of age: The story of the Committee for Economic Development and its impact upon the economic policies of the United States, 1942–1960. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Simmel, G. (1955). Conflict and the web of group affiliations. New York: Free Press.

Sweezy, P. M. (1968). Power elite or ruling class? In G. W. Domhoff & H. B. Ballard (Eds.), C. Wright Mills and The Power Elite (pp. 115–132). Boston: Beacon Press.

Useem, M. (1993). Executive defense: Shareholder power and corporate reorganization. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Vogel, D. (1989). Fluctuating fortunes: The political power of business in America. New York: Basic Books.

Waterhouse, B. C. (2013). Lobbying America: The politics of business from Nixon to NAFTA. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Weinstein, J. (1968). The corporate ideal in the liberal state: 1900–1918. Boston: Beacon Press.

Wrong, D. H. (1968). Power in America. In G. W. Domhoff & H. B. Ballard (Eds.), C. Wright Mills and The Power Elite (pp. 88–94). Boston: Beacon Press.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were funded by the National Science Foundation (grant # SES-0922915) as well as a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mizruchi, M.S. The Power Elite in historical context: a reevaluation of Mills’s thesis, then and now. Theor Soc 46, 95–116 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-017-9284-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-017-9284-4