Abstract

We conducted an experiment to compare subjects’ attitudes toward risk before and after they experienced wealth changes induced by a real-effort task. We identified and estimated the subjects’ levels of reference point adaptation to absolute and relative wealth changes. We found that after experiencing a larger loss than others, the subjects did not completely adapt their reference points to the absolute wealth loss and the relative negative wealth gap, and thus significantly increased their risk-taking behavior. However, the subjects also did not adjust their attitudes toward risk after experiencing a smaller loss than others, a smaller gain than others, or a larger gain than others. This may be because they promptly adapted to wealth changes or because they did not adapt to wealth changes but the effects of absolute and relative wealth changes mostly offset each other.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We allowed the subjects to adjust their previous lottery choices rather than asking them to play a new lottery game in Stage 3 to eliminate the possible effect of expected earnings in Stage 1 on the subjects’ lottery choices in Stage 3.

Although our study focuses on how the reference point is determined by the degree of adaptation to recent absolute and relative wealth changes, it may also be determined by expectations (Kőszegi and Rabin 2006) or aspirations (Diecidue and van de Ven 2008). In a real-effort experiment, Abeler et al. (2011) found support for the hypothesis that the subjects used expectations as a reference point in labor supply decisions. Diecidue et al. (2015) also examined the role of aspiration in an experiment and found that the subjects might make lottery choices with heterogeneous aspiration levels.

Imas (2016) reconciled the mixed findings about whether people increase or decrease their risk-taking after a loss by distinguishing between realized versus paper losses. He found that people take on less risk after a realized loss and more risk after a paper loss.

Gneezy and Potters (1997) studied how the frequency of outcome evaluations influences individuals’ investments in risky assets and explained their experimental results with myopic loss aversion. Although their research focus was different than that of the studies reviewed here, they also compared the investments of subjects who had just experienced a loss with the investments of those who had just experienced a gain and found that the risk taken was only insignificantly greater after a loss.

There is ample evidence that people care not only about their own payoffs, but also about the payoffs of others. See Sobel (2005) for a review.

See Trautmann and Vieider (2012) for an extensive review of this literature.

Shefrin and Statman (1985), Heath et al. (1999), Gneezy (2005), Arkes et al. (2008), and Baucells et al. (2011) examined how the purchase price, historically highest and lowest prices, and current price jointly determine reference points and affect people’s investment decisions. March and Shapira (1992), Sullivan and Kida (1995), and Koop and Johnson (2010) found the reference point to be a function of the status quo, an aspiration level, and a critical survival point.

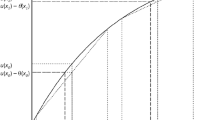

If the possible outcomes of the lottery were both positive and negative, the changes in people’s risk-taking behavior after the wealth changes would be too complicated to analyze using our chosen method. However, most of the real-pay lottery tasks commonly used to measure subjects’ risk attitudes in experimental contexts involve only nonnegative possible outcomes (e.g., Holt and Laury 2002; Dohmen et al. 2010). In our experiments, we use one of these popular lottery tasks, comprising a risky option with an equal chance of a low-value outcome and a high-value outcome, and a safe option generating a fixed outcome. All of the possible outcomes of our lottery task are nonnegative. We thus take this feature into consideration when deriving our hypotheses. Note that here we use only prospect theory, which has been widely implemented in the literature to predict and explain subjects’ choices under uncertainty. Our intention is to study the effects of wealth changes on people’s risk attitudes rather than examining the lottery task itself, which is used simply as a tool to measure the attitudes to risk.

The length of time after a wealth change may also affect the subjects’ adjustment of their risk attitude. For example, Eckel et al. (2009) elicited the risk preferences of Hurricane Katrina evacuees shortly after the event and their risk preferences after 10 months, and found that the risk-seeking behavior of the hurricane evacuees diminished over time. Although the relationship between the size of loss and the speed of reference point adaptation is an interesting topic, we leave it for future research and focus on the relationship between the type of wealth change and the reference point adaptation in this study.

The instructions provided five examples (including switching at the beginning and no switching at all) to help ensure that the subjects did not feel forced to switch or to switch at a certain point.

The threshold level of 4500 ensured a wealth loss for the subjects. In fact, the highest earnings were −100 and the lowest earnings were −4200 in the sessions, with a realized threshold level of 4500 in our data. This design also ensured that the wealth losses were lower than the high-value payment of 4500 generated by the risky option in the lottery task. Thus, the break-even opportunities, in terms of absolute wealth level, were always present in Stage 3.

We did not create wealth changes using pure lotteries. Wealth changes caused by pure luck (a windfall) may have led to the house-money effect, whereas wealth changes generated by real efforts do not (Arkes et al. 1994; Kivetz 1999; Dannenberg et al. 2012; Peng et al. 2013). In addition, the threshold level was randomly selected ex post for each session rather than exogenously determined ex ante. This design was deliberately chosen to minimize the potential discouraging effect for subjects who found it extremely difficult and even nearly impossible to avoid an earnings loss under the situation with an exogenously determined high threshold level. The discouraging effect may have unexpectedly influenced their calculation effort and subsequent risk-taking behavior. Moreover, our design of the calculation task closely mimics the common workplace situation in which individuals’ earnings depend on both their effort and a random shock (created by the random common threshold level) rather than rare situations such as in casinos, where people’s wealth changes depend entirely on luck.

It could be argued that even if the subjects were told to make the adjustment or not based on their wishes, they might still feel the pressure to change their previous choices while facing the same lottery choice tasks. The possible demand effect can be isolated by referring to the results of the control treatment. In fact, we find that the subjects did not change their attitudes toward risk after the calculation task in the control treatment.

Two subjects in the gain sessions started with the risky option and then switched to the safe option in the lottery task. We thus dropped these subjects from the analysis due to their inconsistent lottery choice behavior. In addition, to make the estimation of the reference point feasible, we had to drop 18 subjects who chose only the risky options or only the safe options in all 14 situations in either Stage 1 or Stage 3. Because risk aversion is identified by the switching behavior of the subjects, the risk aversion of a subject cannot be identified when the subject does not switch between lotteries. For example, when a subject only chooses the risky options, we only know that the risk aversion of this subject is bounded below a threshold, but there is no information for us to identify the exact risk aversion of this subject. To achieve consistency, we also dropped these outliers in the other analyses in this study. However, the results are similar for these analyses when we retain these subjects, and are available upon request from the authors.

We do not aim to compare alternative choice models under the risk conditions, or search for the best model to fit the observed changes in risk-taking behavior under various wealth change conditions. These topics may be interesting for future research but are beyond the scope of this study. Instead, we draw on the commonly acknowledged prospect theory to provide a possible explanation for the observed changes in attitude to risk after wealth changes from the less-explored perspective of reference point adaptation.

Studies have found the risk-aversion coefficients in the gain and loss domains to be close (Tversky and Kahneman 1992; Abdellaoui et al. 2007; Booij et al. 2010). However, we were unable to estimate the risk-aversion coefficient in the loss domain in the first step, because all of the possible outcomes of our lotteries were nonnegative. Thus, we imposed the constraint that r is the same across the two domains. This constraint restricted the estimated shape of the utility function, but did not decrease the power of the estimated reference point to explain the changes in attitude to risk.

However, the level of loss aversion is less conclusive in the literature (Kliger and Levy 2009). Some studies have found that it is close to or even insignificantly different from 1 (Prelec 1998; Andersen et al. 2010; Frino et al. 2008), and others have reported higher levels (Tversky and Kahneman 1992; Abdellaoui et al. 2007; Booij et al. 2010). Andersen et al. (2010) argued that in the case of ambiguous reference points (which we attempted to estimate), one cannot simply claim that loss aversion is always present. We thus assume λ = 1 in our main analysis. See the Robustness Checks section for the results under an alternative degree of loss aversion.

Because the two possible outcomes are equally probable, the decision weights assigned to the utility levels of the two outcomes are both equal to 1/2 after probability weighting (Tversky and Kahneman 1992).

Most of the subjects who were assigned the difficult problems in the calculation task faced relatively worse conditions and those assigned with the easy problems faced relatively better conditions. Only one subject completed the difficult problems but earned more than the session average in the loss treatment. Seven subjects in the loss treatment and three subjects in the gain treatment completed the easy problems but earned less than the session average. All of the results remain similar after omitting the observations of the 11 subjects.

The initial risk attitudes elicited in Stage 1 (see Table 3) are not significantly different across conditions except that the subjects in gain-worse are more risk averse than those in loss-worse (p = 0.003) and loss-better (p = 0.047). This pattern in risk aversion is not likely to affect our main results for three reasons. First, our study focuses on how the risk attitude changes after experiencing a wealth change, where the wealth change does not relate to the initial risk attitude. Second, we include a demographic control variable in Table 4, which partly captures the effect of the initial risk attitudes on the risk attitude changes due to wealth change, if there are any. Third, we estimate the initial risk attitude in Table 5 as a part of the structural estimates, which isolates the effect of the initial risk attitudes on the risk attitude changes due to wealth change.

Instead of assuming that the degrees of maladaptation w a and w r are the same across different conditions, we estimated these coefficients separately for each of the four conditions to test for a possible interactive effect between the absolute and relative wealth changes on the reference points. For example, the effect of absolute wealth change on the reference points may depend on whether the relative wealth change is positive or negative. Such an interaction effect of multiple reference points is also reported in the literature (e.g., Viscusi and Huber 2012).

References

Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H., & Paraschiv, C. (2007). Loss aversion under prospect theory: a parameter-free measurement. Management Science, 53(10), 1659–1674.

Abeler, J., Falk, A., Goette, L., & Huffman, D. (2011). Reference points and effort provision. The American Economic Review, 101(2), 470–492.

Ackert, L. F., Charupat, N., Church, B. K., & Deaves, R. (2006). An experimental examination of the house money effect in a multi-period setting. Experimental Economics, 9(1), 5–16.

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Rutström, E. E. (2008). Eliciting risk and time preferences. Econometrica, 76(3), 583–618.

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Rutström, E. E. (2010). Behavioral econometrics for psychologists. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(4), 553–576.

Arkes, H. R., Joyner, C. A., Pezzo, M. V., Nash, J. G., Jacobs, K. S., & Stone, A. E. (1994). The psychology of windfall gains. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 59(3), 331–347.

Arkes, H. R., Hirshleifer, D., Jiang, D., & Lim, S. (2008). Reference point adaptation: Tests in the domain of security trading. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 105(1), 67–81.

Arkes, H. R., Hirshleifer, D., Jiang, D., & Lim, S. (2010). A cross-cultural study of reference point adaptation: evidence from China, Korea, and the US. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 112(2), 99–111.

Bartling, B., Fehr, E., Maréchal, M. A., & Schunk, D. (2009). Egalitarianism and competitiveness. American Economic Review, 99(2), 93–98.

Baucells, M., Weber, M., & Welfens, F. (2011). Reference-point formation and updating. Management Science, 57(3), 506–519.

Boles, T. L., & Messick, D. M. (1995). A reverse outcome bias: the influence of multiple reference points on the evaluation of outcomes and decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 61(3), 262–275.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). A theory of equity, reciprocity and competition. American Economic Review, 90(1), 166–193.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2010). Betrayal aversion: evidence from Brazil, China, Oman, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States: Comment. American Economic Review, 100(1), 628–633.

Booij, A. S., van Praag, B. M. S., & van de Kuilen, G. (2010). A parametric analysis of prospect theory’s functionals for the general population. Theory and Decision, 68(1–2), 115–148.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 817–869.

Coval, J. D., & Shumway, T. (2005). Do behavioral biases affect prices? Journal of Finance, 60(1), 1–34.

Dannenberg, A., Riechmann, T., Sturm, B., & Vogt, C. (2012). Inequality aversion and the house money effect. Experimental Economics, 15(3), 460–484.

Diecidue, E., & van de Ven, J. (2008). Aspiration level, probability of success and failure, and expected utility. International Economic Review, 49(2), 683–700.

Diecidue, E., Levy, M., & van de Ven, J. (2015). No aspiration to win? An experimental test of the aspiration level model. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 51(3), 245–266.

Dohmen, T., & Falk, A. (2011). Performance pay and multidimensional sorting: productivity, preferences, and gender. American Economic Review, 101(2), 556–590.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2010). Are risk aversion and impatience related to cognitive ability? American Economic Review, 100(3), 1238–1260.

Eckel, C., El-Gamal, M., & Wilson, R. (2009). Risk loving after the storm: a Bayesian-network study of hurricane Katrina evacuees. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 69(2), 110–124.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Frino, A., Grant, J., & Johnstone, D. (2008). The house money effect and local traders on the Sydney futures exchange. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 16(1–2), 8–25.

Gertner, R. (1993). Game shows and economic behavior: risk-taking on “Card Sharks.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(2), 507–521.

Gneezy, U. (2005). Updating the reference level: experimental evidence. In R. Zwick & A. Rapoport (Eds.), Experimental business research (pp. 263–284). The Netherlands: Springer.

Gneezy, U., & Potters, J. (1997). An experiment on risk taking and evaluation periods. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 631–645.

Haisley, E., Mostafa, R., & Loewenstein, G. F. (2008). Subjective relative income and lottery ticket purchases. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 21(3), 283–295.

Halko, M.-L., Kaustia, M., & Alanko, E. (2012). The gender effect in risky asset holdings. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 83(1), 66–81.

Harrison, G. W., & Rutström, E. E. (2008). Risk aversion in the laboratory. In J. C. Cox & G. W. Harrison (Eds.), Risk aversion in experiments (Research in experimental economics, Volume 12) (pp.41–196). Bingley: Emerald.

Heath, C., Huddart, S., & Lang, M. (1999). Psychological factors and stock option exercise. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 601–627.

Hey, J., & Orme, C. (1994). Investigating generalizations of expected utility theory using experimental data. Econometrica, 62(6), 1291–1326.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Imas, A. (2016). The realization effect: risk-taking after realized versus paper losses. The American Economic Review, 106(8), 2086–2109.

Kahneman, D. (1992). Reference points, anchors, norms, and mixed feelings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 51(2), 296–312.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Kameda, T., & Davis, J. A. (1990). The function of the reference point in individual and group risk decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 46(1), 55–76.

Keasey, K., & Moon, P. (1996). Gambling with the house money in capital expenditure decisions: an experimental analysis. Economics Letters, 50(1), 105–110.

Kivetz, R. (1999). Advances in research on mental accounting and reason-based choice. Marketing Letters, 10(3), 249–266.

Kliger, D., & Levy, O. (2009). Theories of choice under risk: Insights from financial markets. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 71(2), 330–346.

Koop, G. J., & Johnson, J. G. (2010). The use of multiple reference points in risky decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 25(1), 49–62.

Kőszegi, B., & Rabin, M. (2006). A model of reference-dependent preferences. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(4), 1133–1165.

Linde, J., & Sonnemans, J. (2012). Social comparison and risky choices. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 44(1), 45–72.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2010). Hedonic adaptation to positive and negative experiences. In S. Folkman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 200–226). San Francisco: Oxford.

March, J. G., & Shapira, Z. (1992). Variable risk preferences and the focus of attention. Psychological Review, 99(1), 172–183.

Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1067–1101.

Peng, J., Miao, D., & Xiao, W. (2013). Why are gainers more risk seeking? Judgment and Decision Making, 8(2), 150–160.

Post, T., van den Assem, M. J., Baltussen, G., & Thaler, R. H. (2008). Deal or no deal? Decision making under risk in a large-payoff game show. American Economic Review, 98(1), 38–71.

Prelec, D. (1998). The probability weighting function. Econometrica, 66(3), 497–527.

Seo, M.-G., Goldfarb, B. D., & Barrett, L. F. (2010). Affect and the framing effect within individuals over time: risk taking in a dynamic investment simulation. Academy of Management Journal, 53(2), 411–431.

Shaw, K. L. (1996). An empirical analysis of risk aversion and income growth. Journal of Labor Economics, 14(4), 626–653.

Shefrin, H. M., & Statman, M. (1985). The disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long: theory and evidence. Journal of Finance, 40(3), 777–790.

Shupp, R., Sheremeta, R. M., Schmidt, D., & Walker, J. (2013). Resource allocation contests: experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39, 257–267.

Smith, G., Levere, M., & Kurtzman, R. (2009). Poker player behavior after big wins and big losses. Management Science, 55(9), 1547–1555.

Sobel, J. (2005). Interdependent preferences and reciprocity. Journal of Economic Literature, 43(2), 392–436.

Sullivan, K., & Kida, T. (1995). The effect of multiple reference points and prior gains and losses on managers’ risky decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64(1), 76–83.

Tanaka, T., Camerer, C. F., & Nguyen, Q. (2010). Risk and time preferences: linking experimental and household survey data from Vietnam. American Economic Review, 100(1), 557–571.

Thaler, R. H., & Johnson, E. J. (1990). Gambling with the house money and trying to break even: the effects of prior outcomes on risky choice. Management Science, 36(6), 643–660.

Trautmann, S. T., & Vieider, F. M. (2012). Social influences on risk attitudes: applications in economics. In S. Roeser, R. Hillerbrand, P. Sandin, & M. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of risk theory (pp. 575–600). The Netherlands: Springer.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: a reference-dependent model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 1039–1061.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323.

Viscusi, W. K., & Huber, J. (2012). Reference-dependent valuations of risk: why willingness-to-accept exceeds willingness to pay. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 44(1), 19–44.

Weber, M., & Camerer, C. F. (1998). The disposition effect in securities trading: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 33(2), 167–184.

Acknowledgements

Chun-Yu Ho would like to acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Project No. 71301103).

Xiangdong Qin would like to acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Project No. 71333010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 437 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chao, H., Ho, CY. & Qin, X. Risk taking after absolute and relative wealth changes: The role of reference point adaptation. J Risk Uncertain 54, 157–186 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-017-9257-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-017-9257-z