Abstract

This paper reports the results of experiments designed to test whether individuals and groups abide by monotonicity with respect to first-order stochastic dominance and Bayesian updating when making decisions under risk. The results indicate a significant number of violations of both principles. The violation rate when groups make decisions is substantially lower, and decreasing with group size, suggesting that social interaction improves the decision-making process. Greater transparency of the decision task reduces the violation rate, suggesting that these violations are due to judgment errors rather than the preference structure. In one treatment, however, less complex decisions result in a higher error rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Preference relations having expected utility representation are monotonic with respect to first-order stochastic dominance if and only if the utility function is increasing monotonically in income or in wealth.

Kahneman and Tversky (1972) report such violations. However, their subjects changed their minds once the nature of the alternative involved was made apparent.

See Cooper and Kagel (2005) for a discussion of this issue.

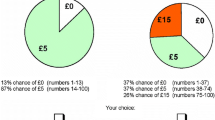

Except in the BCD treatment, described below, where the paying color is not determined until after the first draw.

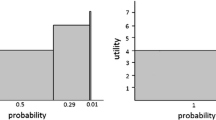

In the case of an initial black draw, there is a 2/3 chance that the state is Up. If the state is indeed Up, then by drawing from the Left side, the subject has a 2/3 chance of drawing another black card. If the state is Down (probability 1/3), then the subject has a 1/3 chance of drawing a black card. Thus, the expected value is 2/3*2/3 + 1/3*1/3 = 5/9. However, by choosing from the Right side for the second draw, the subject has a 2/3 (6/9) chance of drawing a black ball. The calculations are similar for the case of an initial draw of a white card.

We have not investigated group effects for the ABCD treatment, as we are more interested in simpler environments and trying to identify where the truth-wins paradigm breaks down.

To see this, note that α i = α,i = 1,2 implies that

$$ \frac{k_{2}}{_{\left( 1-x\right) ^{2}}}=\frac{k_{1}}{1-x} $$thus \(x^{\ast }=1-\frac{k_{2}}{k_{1}}.\) If α 1 > α 2 then, by the same reasoning, \(\hat{x}<1-\frac{k_{2}}{k_{1}},\) where \(\hat{x}\) is the true value of x. Thus, \(\alpha _{i}^{\ast }=k_{i}/\left( 1-x^{\ast }\right) ^{i}>k_{i}/\left( 1-\hat{x}\right) ^{i}=\alpha _{i},i=1,2.\) Hence,

$$ \frac{\alpha _{2}^{\ast }}{\alpha _{1}^{\ast }}=\frac{k_{2}}{k_{1}\left( 1-x^{\ast }\right) }>\frac{k_{2}}{k_{1}\left( 1-\hat{x}\right) }=\frac{ \alpha _{2}}{\alpha _{1}}. $$We chose to maintain the same marginal benefit for choosing the right color, rather than keeping the same show-up fee and changing the marginal incentives. While it is possible (although unlikely) that the slightly larger show-up fee caused participants to take the task less seriously, this would only serve to lessen the difference between the error rates in individual and group decisions.

This is considerably lower than the aggregate error rate in the ABCD treatment of Charness and Levin (2005). In that experiment, however, the amount paid for a successful draw differed for the two urns, rendering the decision somewhat more complex. Due to this differential payment, not all Bayesian errors in Charness and Levin (2005) reflected violations of first-order stochastic dominance.

The reduction is statistically significant, with Z = − 2.92, and p = 0.004, two-tailed test.

While we cannot be certain why the effect of affect was smaller here than in Charness and Levin (2005), we note that the corresponding ABCD and BCD treatments in that experiment were slightly different, in that people received 7/6 unit for successful draws from the Right side (compared to 1 unit for a successful draw from the Left side). This added a layer of complexity that appears to have affected behavior (note the reduction in the overall ABCD error rate from 48.3 to 38.7%). Perhaps affect is less determinative with simpler problems. In any case, the reduction after success is similar in both cases; the puzzle is the lack of reduction in the error rate after failure, compared to the modest reduction found in Charness and Levin (2005).

See, for example Tversky and Kahneman (1971; Tversky and Kahneman (1973), Kahneman and Tversky (1972), and Grether (1980; Grether (1992). More recent studies (e.g., Ouwersloot, Nijkamp and Rietveld 1998; Zizzo et al. 2000) also provide strong evidence that experimental subjects are often not even close to being ‘perfect Bayesians’.

One person admitted he hadn’t read the instructions. A colleague also suggests that some subjects may simply have been “jerking our chain” by deliberately choosing the dominated strategy.

We cannot use a one-tailed test, as we have no ex ante prediction that error rates will increase going from BCD to CD.

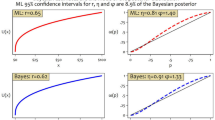

This is the solution to the equations: \(\alpha \left( 1-x\right) =0.294\) and \(\alpha \left( 1-x\right) ^{2}=0.243.\)

The restriction to error rates following success is for the purpose of comparison with the other treatments. The estimated values are based on the solution of the equations \(\alpha _{1}\left( 1-0.174\right) =0.188\) and \( \alpha_{2}\left( 1-0.174\right) ^{2}=0.154,\) where x ∗ = 0.174 and the error rates, 0.188 and 0.154 are from Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Using the methodology of modern experimental economics, Grether (1980) finds evidence of the representativeness bias in a task involving identifying the urn from which a ball was drawn. El-Gamal and Grether (1995) show that people are more prone to the representativeness bias than the conservatism bias. Ganguly, Kagel and Moser (2000) discuss a similar effect. This may help explain why we don’t see a big drop going from treatment BCD to treatment CD, but the observed increase is still surprising.

Charness and Levin (2005) also find this asymmetric improvement from removing affect.

References

Blinder, Alan and John Morgan. (2005). “Are Two Heads Better than One? An Experimental Analysis of Group versus Individual Decision Making,” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 37, 789–811.

Charness, Gary and Dan Levin. (2005). “When Optimal Choices Feel Wrong: A Laboratory Study of Bayesian Updating, Complexity, and Psychological Affect,” American Economic Review 95, 1300–1309.

Charness, Gary and Dan Levin. (2006). “The Origin of the Winner’s Curse: A Laboratory Study,” WP UCSB.

Cooper, David and John Kagel. (2005). “Are Two Heads Better Than One? Team versus Individual Play in Signaling Games,” American Economic Review 95, 477–509.

Edwards, Ward. (1982). “Conservatism in Human Information Processing.” In Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky (eds), Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristic and Biases 359–369, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

El-Gamal, Mahmoud and David Gretcher. (1995). “Are People Bayesian? Uncovering Behavioral Strategies,” Journal of the American Statistical Association 90, 1137–1145.

Ganguly, Ananda, John Kagel, and Donald Moser. (2000). “Do Asset Market Prices Reflect Traders’ Judgment Biases?” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 20, 219–245.

Grether, David. (1980). “Bayes’ Rule and the Representativeness Heuristic: Some Experimental Evidence,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 17, 31–57.

Grether, David. (1992). “Testing Bayes’ Rule as a Descriptive Model: The Representativeness Heuristic,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 95, 537–557.

Kagel, John and Dan Levin. (1986). “The Winner’s Curse and Public Information in Common Value Auctions,” American Economic Review 76, 894–920.

Kahneman, Daniel and Amos Tversky. (1972). “Subjective Probability: A Judgment of Representativeness,” Cognitive Psychology 3, 430–454.

Kerr, Norbert, Robert MacCoun, and Geoffrey Kramer. (1996). “Bias in Judgment: Comparing Individuals and Groups,” Psychological Review 103, 687–719.

Kocher, Matthias and Matthias Sutter. (2005). “The Decision Maker Matters: Individual Versus Team Behavior in Experimental Beauty-contest Games,” Economic Journal 115, 200–223.

Ouwersloot, Hans, Peter Nijkamp, and Piet Rietveld. (1998). “Errors in Probability Updating Behaviour: Measurement and Impact Analysis,” Journal of Economic Psychology 19, 535–563.

Tversky, Amos and Daniel Kahneman. (1971). “Belief in the Law of Small Numbers,” Psychological Bulletin 76, 105–110.

Tversky, Amos and Daniel Kahneman. (1973). “Availability: A Heuristic for Judging Frequency and Probability,” Cognitive Psychology 5, 207–232.

Zizzo, Daniel, Stephanie Stolarz-Fantino, Julie Wen, and Edmund Fantino. (2000). “A Violation of the Monotonicity Axiom: Experimental Evidence on the Conjunction Fallacy,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 41, 263–276.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous referees, Nick Burger, Asen Ivanov, Jim Peck, Tim Salmon, and in particular John Kagel for valuable comments. Charness thanks the Department of Economics at UCSB for funding, Karni thanks the Department of Economics at Johns Hopkins University for funding, and Levin thanks the National Science Foundation for funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Charness, G., Karni, E. & Levin, D. Individual and group decision making under risk: An experimental study of Bayesian updating and violations of first-order stochastic dominance. J Risk Uncertainty 35, 129–148 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9020-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9020-y