Abstract

Despite a robust body of literature about the choice of students’ first postsecondary institution, we have little insight regarding transfer from four-year colleges and universities across socioeconomic groups. In this study, we argue that when entry to selective colleges reaches a heightened level of competitiveness, transfer may be employed by students from advantaged social backgrounds as an adaptive strategy to gain access. Using multinomial logistic regression, this study draws on data from BPS:04/09 to uncover whether transfer functions as a mechanism of adaptation that exacerbates class inequalities in higher education. We found that students from higher-socioeconomic quartiles who first enrolled in a selective institution are most likely to engage in lateral transfer, but mainly to another college even more prestigious. This study provides evidence of the role of college transfer in exacerbating class inequalities in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Though rates of transfer among four-year college students closely resemble those from community colleges, we know far less about their motivations for doing so. Indeed, 37% of students who first attended two-year colleges in 2011 eventually transferred to another institution, but the transfer rate for four-year college students was similar at 39% (Shapiro et al., 2018). Comparatively, while the vertical transfer pathway from community colleges is widely known and understood as a democratizing function of community colleges, less attention is given to trajectories best described as nonlinear—including lateral transfer between 4-year institutions and reverse transfer from 4-year to 2-year institutions. Research suggests that there are myriad considerations for nonlinear transfer decisions, such as a change in curricular program of study, limited institutional integration, academic challenges, and college affordability (Crisp et al., 2021; Goldrick-Rab & Pfeffer, 2009; Ishitani & Flood, 2018; Li, 2010). However, escalating competition for admission to selective colleges and universities may also affect students’ subsequent enrollment behaviors, particularly those from the most advantaged socioeconomic (SES) groups. As admission to prestigious institutions has become increasingly difficult, privileged students—those best positioned to engage in adaptive strategies that circumvent exclusionary mechanisms—may look to transfer as an option if they are initially unable to access their preferred instiution.

Prior scholarship has investigated a number of ways that enrollment patterns in higher education are highly stratified by socioeconomic status. In particular, many sociologists have found that postsecondary pathways differ by social background regarding the sector and selectivity of initial college choices (Alon, 2009; Davies & Guppy, 1997; Hearn, 1984, 1991; Roksa et al., 2007; Zarifa, 2012). Through the breadth of this vast body of literature, researchers have consistently demonstrated that students from low-SES groups are disadvantaged in accessing selective colleges and universities. What remains relatively understudied are the ways that students’ college trajectories evolve after the initial point of entry. Specifically, are there differences in the ways that higher-SES students engage in transfer to expand class advantage?

There is a small body of literature regarding student mobility that has examined variation by the sector of transfer destinations (Crisp et al., 2021; Goldrick-Rab & Pfeffer, 2009; Kalogrides & Grodsky, 2011) and the fluidity of student movement between institutions (Goldrick-Rab, 2006; Ishitani & Flood, 2018). Yet apart from whether or how four-year college students may engage in transfer, the extent of where they enroll is still unclear. Specifically, this study asks: Do the transfer destinations of students who first enroll in four-year colleges and universities vary by socioeconomic status? The current study builds on the aforementioned body of literature by considering how college transfer functions as a potential strategy to perpetuate class inequalities. In this article, we argue that lateral transfer functions as a strategy of adaptation, serving as a pathway for the most affluent students to maintain their privilege in an increasing competitive landscape of college admissions.

Theory and Prior Literature

We begin with a review of literature informing the empirical and theoretical basis for the investigation. We first provide background regarding shifts in the U.S. higher education landscape that coincide with changing student mobility patterns before turning to our theoretical framework regarding the expansion of class inequality that may help to explain variation in the potential motivations for transfer destinations.

Rising Competition within U.S. Higher Education and Socioeconomic Advantage

The mounting pressure of competition best defines the current context of selective college admissions. Hoxby (2009) argues that students in previous decades were far more sensitive to the distance of their home to their potential college; but as the costs of long-distance travel decreased over time, “students, especially high-aptitude students, are far more sensitive to a college’s resources and student body” (p. 102). Given the privileges afforded to students who attend elite colleges and universities (Brewer et al., 1999; Dale & Krueger, 2002; Cohodes & Goodman &, 2014; Hoekstra, 2009; Hout, 2012), it is unsurprising that demand for these institutions have steadily increased (Bound et al., 2009). For example, at elite institutions, “graduation is more certain (Bowen et al., 2009) and investment per student is higher (Hoxby, 2009)” (Hout, 2012, p. 388). Given such privileges, studies have shown significant economic returns for students attending elite private institutions (Brewer et al., 1999), particularly for students from low-SES backgrounds (Chetty et al., 2017; Dale & Krueger, 2002).

College rankings such as the U.S. News and World Report have played a significant role in exacerbating the admissions frenzy as more students report that these resources have a considerable influence on their college choice (Espinosa et al., 2014; Weis et al., 2015). As a result, many students now seek entry into the highest-ranked institution possible as opposed to merely any selective institution (Avery et al., 2004). This is especially the case for those from high-SES and upper-middle-SES backgrounds. As Weis and colleagues (2014) argue,

In a historic moment marked by deep economic uncertainty and accompanying class anxieties..a particularly located segment of largely, but not entirely, White and affluent parents and students in relatively privileged secondary schools individually and collectively mobilize all available and embodied cultural, social, and economic capital to carve out and instantiate..a ‘new’ upper middle class via entrance to particular postsecondary institutions (p. 3).

But less prestigious institutions have also experienced a commensurate increase in applications as demand intensifies. College Board reports that between 2002 and 2012, the average admit rate for colleges defined as the most competitive declined from 31.4 to 21.65%, while rates for the least competitive colleges also dropped by approximately 6 percentage points (Hurwitz & Kumar, 2015). Increased costs associated with attending higher education have also channeled many “high-achieving, affluent, and middle-income students, who in earlier years might have attended first- and second-tier private colleges and universities” into public flagship institutions (Bowen et al., 2009, p. 263). This shift altered the incoming student profile attending flagships—both academically and demographically—arguably pushing others out as selectivity increased across these institutions. As the selectivity of institutions “snowballs” from one tier to the next, the least privileged students become further segregated to noncompetitive colleges (Contreras, 2005).

To manage high demand, selective schools have historically increased their reliance on standardized test scores as the dominant criteria for admissions. Overreliance on the SAT/ACT relative to other holistic criteria has resulted in a “shifting meritocracy” in which higher-socioeconomic groups maintain an admissions advantage given their access to test preparation supports (Alon & Tienda, 2007; Bastedo & Jaquette, 2011). Even still, college admission has become far more precarious for all applicants, as many selective schools admit less than 20% of their application pool, on average, while the most elite institutions regularly admit between 5% and 10% (Hurwitz & Kumar, 2015). For instance, Avery and colleagues (2004) demonstrate that even for the most meritorious students in their sample who scored in 100th percentile of the SAT, only one in every five who applied to Harvard in 2004 received admission. Given the gamble regarding entry into one’s preferred institution, many students may have to rethink how they play the “admissions game” (Bound et al., 2009).

Students from higher-socioeconomic groups are significantly advantaged in the process of preparing for transitions to and through higher education. Research shows that affluent parents are actively involved in the process of “concerted cultivation” (Lareau, 2003; Lareau & Weininger, 2008) in which their children’s educational experiences are oriented to best prepare them strategically for postsecondary planning. Examples of such strategic preparation may include placement in advanced academic tracks (Lucas, 2001), private college counseling (McDonough et al., 1997), and engaging in academic and nonacademic enhancement strategies to bolster their profile in the college application process (Wolniak et al., 2016). This level of college preparation contrasts considerably with students from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds, who often face a number of barriers to access the knowledge and dominant forms of capital required to navigate the college-going process with ease (Cipollone & Stich, 2017; Deil-Amen & Tevis, 2010).

One reason for class differences in college preparation pertains to the acquisition of dominant cultural capital—or rather the norms, behaviors, and knowledge of one’s social class (Bourdieu, 1986; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990). Because priviledge begets privilege, students from high-SES backgrounds tend to embody the types of cultural capital that allow them to better position themselves for continued advantage. For example, studies show that students from higher-socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to possess the “know-how” required to navigate bureaucratic hurdles (Rosenbaum et al., 2006), and when uncertain, are more comfortable seeking out support from authority figures (Jack, 2016). Moreover, high-SES parents also supply their offspring with ample resources while in college by supplementing the advising provided by institutions in addition to affording considerable financial investments (Hamilton et al., 2018; Weis et al., 2015). In sum, students from the upper-SES strata are better able to position themselves for class advantages via adaptive strategies. Thus, for more privileged students unable to secure admission to the initial institution of their choice, college transfer may function as a strategy to ensure the transmission of advantage.

Effectively Expanding Inequality via Exclusion and Adaptation

In order to explain the persistence of disparities within an expanding system of education, Raftery and Hout (1993) argued that inequality is maximally maintained by the ability of privileged groups to take advantage of opportunities to secure higher levels of education. The authors argue that once socioeconomically privileged groups reach a point of saturation at any particular level of education, they will then seek out opportunities at the next level. Because privileged groups are better positioned to secure these opportunities, inequality remains maximally maintained within the system. In addition to the quantitative outcomes high-SES groups are better positioned to secure (e.g., greater number of years of education, higher credentials, etc.), Lucas (2001) extended this thinking to account for the qualitative differences that accompany postsecondary expansion. According to Lucas (2001), even when high-SES groups reach a point of saturation at any particular level of education (e.g., secondary schools), these groups will further ensure that they maintain class advantage by seeking out and safeguarding qualitatively different educational experiences—thereby working to effectively maintain inequality (EMI). For example, Lucas (2001) argued that once high school completion became more universal, high-SES groups sought out qualitatively different educational opportunities within the same education level to gain advantage (e.g., advanced course taking).

Further extending the work of Lucas (2001) to the context of higher education, Alon (2009) argues “that as a larger share of high school graduates reaches some form of higher education, class differences in access to selective college destinations becomes more prominent to preserve the status hierarchy” (p. 732). Indeed, this becomes clear as we look to the contemporary context of higher education and increasingly competitive admissions standards. It is no longer enough to merely enroll in and graduate from any college; instead, social status is maintained and perpetuated with the gravitas afforded by attending the most prestigious schools. For Alon, the mechanisms of adaptation and exclusion exacerbate class inequalities in college enrollment. Specifically, an increased reliance on test-scores in college admissions perpetuates a meritocratic system that facilitates exclusion to selective colleges and universities while also enabling students from high-SES backgrounds to employ strategies of adaptation (e.g., test-preparation, etc.) that ensure the transmission of privilege. Using data from three nationally representative cohorts, Alon (2009) found that class divisions in access to selective institutions have been the widest when competition and demand are high.

Students from high-SES backgrounds may similarly use the option of transferring as an adaptive strategy to overcome their initial exclusion to selective colleges and universities. Indeed, research regarding nonlinear transfer behavior reveals two consistent trends: while high-SES students are least likely to leave their first institution at all, among those who do so, a higher proportion transfer laterally to another four-year college whereas the least advantaged students are more likely to transfer to community colleges (Crisp et al., 2021; Goldrick-Rab, 2006; Goldrick-Rab & Pfeffer, 2009; Spencer, 2021). In a logistic regression analysis using data from the National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS:88), Goldrick-Rab and Pfeffer (2009) found that lateral transfers are more likely to come from advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, net of other factors. Because these students were not found to be academically underprepared like those who transfer in reverse, the authors speculate that these students may instead be motivated by the desire to find a “better” school given their socioeconomic privileges. Thus, mounting competition may induce the use of transfer as an adaptive strategy of “prestige-seeking” for affluent students to access more selective institutions (Alon, 2009). For this reason, we hypothesize that socially advantaged students who fail to gain initial entry into their preferred institution may transfer at a later time to increase the odds of attending a more selective institution.

Methods

Data

For this investigation, we draw on data from the 04/09 Beginning Postsecondary Students (BPS) Longitudinal Study. The BPS:04/09 is a nationally representative, longitudinal study tracking 18,640 sample members from the period of enrolling as first-time freshmen at colleges and universities throughout the country for a period of six years. Specifically, the cohort of students first enrolled in postsecondary institutions during the 2003–2004 school year. Data from the study are restricted and maintained by the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). The richness of the data for these students facilitates the opportunity to track enrollment behaviors longitudinally at multiple institutions nationwide.

Although the 04/09 BPS cohort were enrolled in college more than 15 years ago, the observed years capture a unique period in college admissions that is well-suited for our investigation. Indeed, the 2004 BPS cohort first enrolled during a precarious time for students seeking admission to selective colleges and universities. College Board’s American Survey of Colleges demonstrates that between 1996 and 2003, admit rates at the top private colleges dropped by 7.7 percentage points and by 11.26 percentage points at the top public institutions, on average (Bound et al., 2009). These declines were considerable compared to the minimal changes in admit rates that occurred from the 1980s through most of the 1990s. Given Alon’s (2009) theory that class divisions in access to selective institutions widens when admission to these schools is most difficult, we hypothesize that transfer activity will become especially pronounced during heightened periods of competition.

Sample

We introduced a number of restrictions to define the sample for our analysis. First, we restrict our sample to undergraduates under the age of 25 following past investigations of transfer activity (Goldrick-Rab, 2006; Goldrick-Rab & Pfeffer, 2009; Kalogrides & Grodsky, 2011). Compared to recent high school graduates, older, nontraditional students often have responsibilities external to their experiences in higher education that affect their enrollment trajectories differently (Calcagno et al., 2007; Zarifa et al., 2018). By restricting the sample to traditional-age students, we are also able to employ variables derived from high-school transcripts, which are excluded in BPS for observations over the age of 24.

Second, given the study’s focus to examine instances of nontraditional transfer pathways, the sample is also conditioned to only include first-time, undergraduates who initially enrolled at a four-year college or university. Hence, students who first enrolled at two-year institutions or who were co-enrolled at more than one institution were excluded from the analysis. In our final restriction, we also exclude observations missing data for the dependent variables (approximately 20 observations) and parental education status (approximately 70 observations), which is used to construct the primary independent variable of interest for our analysis (discussed further below). These restrictions have resulted in an analytic sample of 6,880. The sample size is rounded to the nearest ten per compliance with IES requirements for restricted data.

Empirical Strategy

We employ multinomial logistic regression (MLR) to answer our research questions regarding differences in transfer destinations. Specifically, MLR models dependent variables with multiple categorical options, simultaneously producing parameter estimates for each possible outcome with exception to the base category. In other words, this approach facilitates the ability to estimate the association between student characteristics and behaviors related to the probability of transferring to a particular type of college destination. MLR is preferred to binary logistic regression, which cannot account for all possible outcome categories simultaneously and thus limits an understanding of the nuances in students’ transfer choices. In contrast, this study examines the importance of social background factors in predicting the quality of transfer destinations. A general form of the MLR model can be expressed as follows:

where the probability of observing a particular transfer outcome j (e.g., moving to a particular institution type) for individual i when there is a total of j possibilities, x is a vector of our independent variables, and β is a vector of coefficients for these variables. Furthermore, because the BPS dataset is derived from a complex sampling design, all regression models employ sampling weights, the primary sampling unit, and strata to correctly estimate the variance and to make statistically valid inferences to the population. With the (“svy”) command in Stata 17.0, we use the WTC000 analysis weight.

Variable Descriptions

Defining Qualitative Differences in Transfer Destinations

Three multi-category dependent variables are constructed to capture qualitative distinctions in transfer destinations. To construct these measures, we began by using the Postsecondary Education Transcript Study (PETS) data to identify the first and second institutions attended for all BPS:04/09 sample members. We then used the transcript-level data to classify lateral or reverse forms of transfer for the first incidence of transfer based on the level of a student’s origin and destination institutions.

For two of the three variables, we further classified lateral transfer based on the institutional quality of students’ second enrolled institution using the 2004 version of Barron’s Admissions Competitive Index. Barron’s assigns four-year colleges in their profile to one of seven selectivity categories according to the school’s overall admissions rate and the average characteristics of their freshman cohort including students’ SAT scores, cumulative high-school GPA, and class rank. Although it is possible to measure college quality in a multitude of ways, the Barron’s index is preferred to other measures that rely solely on one criteria of selectivity as a proxy measure of both competitiveness and prestige.

The Barron’s Index successfully categorizes the first institution for 83% of BPS sample members who initially enrolled in four-year colleges and universities, and 96% of the second institutions for these students who engaged in lateral transfer. Because Barron’s does not rank all institutions of higher education, some institutions were classified using measures of corresponding selectivity levels from PETS and the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). Despite employing this additional classification approach, the transfer destinations for less than 1% of the sample could not be identified and were, therefore, dropped from the samples as aforementioned in the previous section. Using the Barron’s Index and IPEDS categorizations, we generated three dependent variables as follows:

Transfer Destination Type

. The first dependent variable defines nonlinear transfer options by the level of students’ second enrolled institution. In other words, this measure distinguishes reverse transfer for students who moved to a two-year college and lateral transfer if they moved to another four-year institution. For this measure and all other dependent variables, the option of never transferring is used as the base category. Thus, “never transfer” is coded as 0, while “lateral transfer” is coded as 1, and so on.

Transfer Destination Selectivity

. For the second dependent variable, we create five classifications to represent the selectivity of students’ second institution by collapsing the categories from Barron’s Index (presented in parentheses), which vary according to their rank in the distribution of competitiveness. Following other scholars using the Barron’s Index as a proxy for college quality, the remaining categorizations are re-grouped “due to the thinness of data and for ease of interpretation” (Smith et al., 2013, p. 250). In other words, we collapse the Barron’s categories because of data considerations, specifically the sample sizes for groupings, but the other reasons are also conceptual and grounded in the prior literature.

Our first category represents the most selective institutions (most competitive) in which the common criteria for admissions includes a median math or verbal SAT score of 655 to 800, class rank in the top 10–20%, and a GPA of B + to A (Schmitt, 2009). We distinguish the most selective institutions from those we classify as highly selective (highly competitive and very competitive) given the differences that Bastedo and Flaster (2014) argue are “quite substantial in terms of resources and effects” (p. 95). According to Hurwitz and Kumar (2015), institutions classified as the most competitive in 2002 admitted only 31.4% of their applications on average—a rate considerably lower than the average for institutions in the next category (56.3%).

Our third and fourth categories respectively represent moderately selective colleges (competitive), which admit 75 to 85% of all applicants, and the least selective colleges (less competitive and noncompetitive) that accept 85% or more of applicants (Schmitt, 2009). There were only a few observed instances (approximately 20) in which students transferred to colleges categorized by Barron’s as “Special”, which captures schools offering a specialized, or art-related program of study. Although these institutions do not neatly align with our study’s interest in comparing the selectivity of schools, we decide to keep sample members who attended these schools by folding them in the “least selective” category as opposed to dropping them from the sample altogether. We also replicated our models by excluding these observations to test whether the estimates are sensitive to their inclusion, but the main results are largely unchanged. Lastly, we separate two-year colleges into our final non-selective category in order to distinguish students who engage in reverse transfer behavior.

Transfer Destination Direction

. The third dependent variable captures differences in the directionality of transfer movement. In this categorization of transfer, a students’ first institution is similarly classified as their second using the Barron’s index categories and IPEDS. By comparing the Barron’s index rankings for transfer students’ first and second institutions, we categorize whether their move can be defined as ascending transfer (e.g., competitive to most competitive), descending transfer (e.g., most competitive to competitive), or parallel transfer (e.g., competitive to a competitive). Hence, we are able to capture whether students are transferring strategically. For instance, students who transfer to institutions ranked higher in competitiveness may be more likely to move due to “prestige-seeking” motivations compared to students who transfer in other directions.

Parental SES

The key independent variables of interest for this investigation identifies differences across categorizations of SES. A principal component analysis was used to construct our SES measure based on three items: (1) the total income in 2002 for independent students or the parents of dependent students, (2) parents’ highest level of education, and (3) income as a percent of the federal poverty level threshold in 2002. Though SES is also commonly defined according to parental occupation, this information is not available in BPS:04/09. The variables loaded into three factors in which the first component, a linear combination of the aforementioned variables, represents an index of SES. The first component is an optimal composite indicator that contains 72% of the original standardized variance.

We then divided the composite indicator into four dichotomous indicators representing SES quartiles, which serve as the independent variables of interest for our MLR models: high-SES, upper-middle-SES, lower-middle-SES, and low-SES (reference category). We identify low-SES students if their SES composite score fell within the lowest 25% of the unweighted sample distribution, high-SES student scores fell within the top 25%, and so on. The use of quartiles is commonly employed in research of socioeconomic differences (Bastedo & Jaquette, 2011). Table 1 summarizes the characteristics for each SES quartile by presenting the weighted means and proportions for key indicators. The table shows that, on average, the 2002 household income of low-SES students in our sample was $23,844 compared to $50,663 for the lower-middle-SES group, $80,705 for upper-middle-SES students, and $149,201 for high-SES students. Notably, low-SES students, on average, come from families with an income below 185% of the federal poverty level, which is the eligibility threshold used for many governmental mean-tested programs such as free- and reduced-price meals (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Furthermore, the typical parental educational achievement level of low-SES students was only a high school diploma or less, but nearly all upper-middle-SES and high-SES students came from college educated families with either a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Covariates

Several measures are included in the models to account for other explanatory factors associated with students’ enrollment decisions. In addition to dichotomous measures for race/ethnicity and gender, degree aspirations were also captured with dummies for the highest level of degree that was expected at baseline. We then account for pre-college related factors including indicators of high school type, cumulative high school GPA, and whether or not pre-college level credits were earned. Because first-year academic achievement and enrollment behaviors are highly associated with transfer decisions, we also control for first-year grade point average, part-time enrollment status, remedial coursework enrollment, whether the academic major was undecided, and whether enrollment was delayed after graduating from high school. We also control for financial demands associated with student enrollment behavior including indicators for hours worked in the first year of enrollment, the cost of tuition and fees for the first institution, and the total amount of student loan debt in the first-year (Bozick, 2007; Goldrick-Rab, 2016).

Finally, given the importance of a student’s initial college choice, we control for factors related to their first-year experience. These factors include students’ initial living arrangements and the distance from a respondent’s home to their first institution (Turley, 2009). We also include measures of selectivity for the first enrolled institution using the Barron’s Index, which are coded similarly as the aforementioned dependent variable capturing the selectivity of transfer destinations. Given the small number of students in our sample who initially enrolled in the most selective colleges and universities (See Table 2), our MLR models only include selectivity dummies for the least and moderately selective institutions—thus leaving students who initially enrolled in all top colleges and universities (defined as the most selective and highly selective) as the reference category.

Limitations

There are limitations of this analysis that are important to note. It is most noteworthy to caution the reader regarding causal inferences. This study is principally interested in understanding the relationship between socioeconomic status with transfer destinations, so our approach is not intended to make any causal claims regarding the observed findings. While we have incorporated robust covariates in our models to account for other confounding explanations of transfer, there are a number of complicated time-invariant and time-varying factors affecting students’ enrollment decisions that may be unobserved.

Our dependent variables are also imperfect as there are no ideal ways to observe the nuanced distinctions in college quality. In particular, the Barron’s Index, though a commonly used proxy to measure college quality, is limited by its primary emphasis on admissions competitiveness and selectivity. Furthermore, because the employed Barron’s index classifies institutions by group, it is unclear whether transfer could occur within a given category. Consider a student who first enrolls at Boston College: the student would not be categorized as engaging in ascending transfer activity if she moved to a similarly ranked institution like Harvard University. In such a scenario, the distinctions in prestige that the two colleges signal culturally may be evident to students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, but capturing such a qualitative difference between institutions is also a challenge to quantify. Therefore, lateral transfer may also occur through a more intricate level of prestige-seeking behavior that is not captured by the study.

That said, we are also unable to fully explain why some students may move from one institution to another. Although our analysis of transfer destination direction offers evidence that could be construed as “prestige-seeking” behavior for those moving in an ascending direction, we are unable to claim that this is always the case absent survey data or an examination of student motivations using qualitative research methods. Because students’ motivations for lateral movement are complex, we cannot fully account for all potential reasons that students may choose to leave their first institution. Certainly, students may transfer for reasons that are not examined such as a change in program of study or personal circumstances, among others. But while our study is limited in what we can actually measure, it is important to note that the findings from this study are interpreted through a sociological lens. In other words, given the aforementioned theoretical grounding, we interpret evidence of socioeconomic differences in the type of transfer destinations as a perpetuation of stratified enrollment trajectories in higher education.

Findings

Descriptive Analysis

Characteristics of the Sample

Table 2 presents weighted descriptive statistics for the full sample of four-year college students juxtaposed with the characteristics of those who never transfer, those who engaged in lateral transfer, and those who reverse transfer. Among the full sample, the majority of students are from White, middle-SES backgrounds (upper-middle and lower-middle). Most also attended public high schools and a large proportion performed well academically before college, but nearly half had a first year GPA of C or lower. The majority were enrolled full time, lived on campus (275 miles from home, on average), did not work while enrolled, and had expectations for advanced educational credentials. Very few students first enrolled at one of the most selective colleges. Instead, 30% first attended highly selective institutions, 41% attended a moderately selective college, and 22% attended one of the least selective four-year colleges and universities.

The table also shows that 74% of students never transfer (n = 5,070), while nearly 19% transfer laterally and 7% transfer in reverse. Relative to those who never transfer, there is a higher proportion of lateral transfer students who identify as White and female from high-SES and upper-middle SES backgrounds. More lateral transfers also initially lived on campus and first enrolled at highly selective colleges. In contrast, there is a higher proportion of reverse transfer students from low-SES, Black, and Hispanic/Latino backgrounds. Students who reverse transfer also tend to be lower-achieving academically as indicated by their high school and college GPAs, remedial course-taking, and their initial enrollment at the least selective and moderately selective colleges.

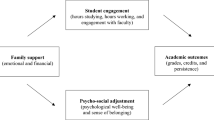

Trends in Transfer Behavior

Figure 1 presents the transfer rates of four-year college students to institutions of varying selectivity levels by SES. It shows that few students from any background transferred to one of the most selective colleges (< 3% of all groups). But nearly 8% of upper-middle-SES students and 10% of high-SES students transferred to highly selective schools: rates that were more than two to three times higher than low-SES students. Compared to other school types, nonselective colleges were the most popular destination for transfer students from lower-middle SES and low-SES backgrounds.

Rates of Transfer Among Four-year College Students, by Socioeconomic Status and Transfer Institution Selectivity

Source. BPS: 2004/2009.

Notes: Proportions are reported for each SES group by the selectivity of their first college. The sample sizes for each SES group are as follows: High SES (n = 1,730), Upper-Middle SES (n = 1,730), Lower-Middle SES (n = 1,700), and Low SES (n = 1,720). Estimates are survey weighted. Selectivity is determined using the 2004 version of Barron’s Admissions Competitive Index.

Table 3 further disaggregates rates of transfer for each SES group by the selectivity level of their first and second institutions. Consistent with the literature, a higher proportion of high-SES students first enrolled at the most selective and highly selective colleges, especially compared to low-SES students, who were more likely to start at the least selective and moderately selective schools (Bowen et al., 2009; Carnevale & Rose, 2004; Smith et al., 2013). Nonetheless, students of all backgrounds who attended the most selective schools were the least likely to transfer.

Of those who did transfer, a higher proportion of middle- and high-SES students at the top schools (most selective and highly selective) moved to a school of similar selectivity as opposed to one less competitive. In contrast, a higher proportion of low-SES transfers, from all school types moved “down” to less selective institutions. But transfer students from high-SES backgrounds who first enrolled at the least selective colleges and universities were more likely to move “up.” For instance, nearly 8% of high-SES students at the least selective institutions moved to moderately selective colleges and 6% moved to a college defined as highly selective. In contrast, only 1% of low-SES students at the least selective institutions moved to a college defined as highly selective.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis

Though the descriptive trends suggest that students from the highest socioeconomic groups may aspire to attend more prestigious institutions at a higher rate compared to other groups, it does not provide evidence that the relationship between transfer behavior and SES is salient above and beyond other potential explanatory factors. Thus, we now turn to the results from our multinomial logistic regression analyses which allows us to account for multiple influences on transfer behavior. In this effort, we do not attempt to make causal inferences, but rather, we interpret all findings as associations between our variables of interest with the outcomes. All coefficients from the MLR models are presented as average marginal effects for ease of interpretation.

We begin by reviewing the results for nonlinear transfer activity defined by destination type, which essentially replicates the approach by other scholars in the literature who juxtapose transfer to another four-year college versus transfer to a two-year college (Crisp et al., 2021; Goldrick-Rab & Pfeffer, 2009). We subsequently present the results for transfer according to the destination selectivity level. Finally, we conclude with results identifying the directionality of transfer movement, which will allow us to ascertain differences across SES groups in the potential aspirations associated with transfer behavior.

Variation in Nonlinear Transfer Destination Type

Table 4 presents results from MLR models for transfer destination type defined by institutional level. In these models, we distinguish between lateral and reverse transfer, compared to never transferring. Model 1 shows estimates for only the SES measures of interest and other socio-demographic characteristics. Model 2 presents the results after controlling for pre-college, high school influences and Model 3 adds controls for postsecondary factors at baseline. The results in Model 1 suggest that, controlling for race/ethnicity and gender, there is a relationship between SES and nonlinear transfer behavior: the probability of engaging in lateral transfer relative to never transferring is higher for students from the upper-middle SES group and high-SES group compared to those from the low-SES group, on average; but the probability that the more advantaged students would transfer in reverse is lower by 3 percentage points. These findings are fairly consistent with the observed descriptive trends. However, Model 3 shows that these relationships with lateral transfer are no longer statistically different from zero after accounting for pre-college and postsecondary factors. Model 3 does show, however, that upper-middle-SES students have a lower probability of transferring in reverse, net of other influences.

The results show that there were other significant determinants of transfer consistent with the prior literature. Corresponding to the research on retention, students who transferred to two-year colleges were more likely to work, on average (Bozick, 2007). Model 3 also shows that there is a positive relationship between lateral transfer with the distance between a student’s home and their first institution. This suggests that students who engage in this form of enrollment behavior are unlikely to be place-bound and, therfore, more inclined to make decisions about their enrollment for reasons other than location (Turley, 2009).

Relative to never transferring, there was also a statistically significant relationship between nonlinear transfer with earning a GPA of C average or lower (from high school or the first year of college), controlling for other factors. This finding further demonstrates that indicators of academic achievement were among the most relevant explanatory factors of reverse transfer (Crisp et al., 2021; Goldrick-Rab & Pfeffer, 2009; Kalogrides & Grodsky, 2011). Hence, reverse transfer may serve as a pathway for “cooling out” among students who first enroll at four-year colleges—facilitating student persistence, albeit in a sub-baccalaureate degree program (Clark, 1960). In contrast, lower academically-achieving students were less likely to transfer laterally.

Variation in the Selectivity of Nonlinear Transfer Destinations

We now turn to our examination of differences in transfer destination selectivity using collapsed categories from the Barron’s Admissions Competitive Index in Table 5. Consistent with the results from Table 4, upper-middle-SES students are less likely to transfer to nonselective institutions. But controlling for other influences, the probability of transferring to a highly selective college or university relative to never transferring is nearly 5 percentage points higher for upper-middle-SES and high-SES students compared to low-SES students, on average. Therefore, while there is no statistically significant relationship between SES and lateral transfer, broadly defined, there appears to be an exception when lateral transfer is further distinguished by levels of selectivity. Indeed, upper-middle- and high-SES students are most likely to transfer specifically to selective institutions, which is obscured by the general lateral transfer category.

But while the SES coefficients are statistically significant after controlling for the selectivity of their first intuition, we cannot conclude from the results in Table 5 alone that these students are transferring to a college more prestigious than their first. Thus, in Table 6 we further distinguish the differences between the selectivity of students’ first and second institutions by categorizing the directionality of transfer movement. The dependent variable for this MLR analysis categorizes students who transferred to an institution with a similar Barron’s selectivity rating (parallel) versus one higher (ascending) or lower (descending) than their first college. In other words, if students transfer to institutions that are ranked higher than their first institutions, this ascending form of transfer movement can be reasonably construed as strategic: one that is motivated by an interest to enroll in the most competitive college possible.

Model 1 presents the MLR results without controlling for the selectivity of students’ initial institution and shows that there is no relationship between SES and transfer movement directionality. But after adding indicators for initial institutional selectivity—specifically least and moderately selective college dummies—we do find a statistically significant association of SES. Table 6 shows that, relative to never transferring, the probability of high-SES and upper-middle-SES students engaging in ascending forms for transfer (i.e., transferring to a more selective institution from the one they initially enrolled in) is higher than low-SES students by 4 and 3 percentage points respectively. However, this relationship is specific to students who first enrolled in one of the colleges and universities defined by the Barron’s Index as highly competitive and very competitive. The results show that upper-middle SES and high-SES students at top schools are, indeed, transferring laterally to other selective schools; but they are not merely going from one good school to another—they are instead moving from one good school to another that is ranked higher and arguably can be defined as qualitatively “better.”

Discussion

Along with the vast expansion of higher education access in recent decades, there has also been a commensurate shift in enrollment behavior that varies by social background. Yet, despite increased competition for access to selective colleges and universities, prior research has not considered the potential role of transfer activity in further advantaging socioeconomically privileged students. This study contributes to the literature by examining qualitative distinctions in transfer trajectories for students who first enrolled at four-year colleges and universities in the early 2000s, when entry to selective colleges and universities reached a heightened level of competitiveness. Grounded by the theoretical underpinnings of Alon (2009) and Lucas (2001), our investigation sought to uncover whether transfer functions as a mechanism of adaptation that exacerbates class inequalities in higher education. We found that lateral transfer activity among traditional-age students was concentrated among those from socially advantaged backgrounds who first enrolled in a selective institution and later moved to one even more prestigious.

Net of other factors, we found no statistically significant difference between SES groups in the probability of lateral transfer, broadly defined; however, our findings suggest that there is variability by social background within the lateral transfer distinction when classified by levels of selectivity. Relative to never transferring, students from advantaged backgrounds were more likely to transfer to highly selective institutions compared to those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, on average. These findings suggest that lateral transfer operates to exacerbate class inequalities at top colleges and universities, which already disproportionately enroll students from the highest socioeconomic strata (Bowen et al., 2009; Carnevale & Rose, 2004; Smith et al., 2013). As presented in Table 3, only 21% of the students from low-SES families initially enrolled at one of the most selective or highly selective colleges compared to 57% of students from the highest socioeconomic quartile. Taken together with research regarding initial college entry (Alon, 2009; Davies & Guppy, 1997; Hearn, 1984, 1991; Roksa et al., 2007; Zarifa, 2012), it is evident that students from higher-socioeconomic backgrounds are clearly advantaged in multiple admissions pathways to selective institutions.

Notably, the country’s most selective colleges and universities were not the primary transfer destinations among students from the top SES quartiles. That there was no difference between SES groups in transfer to elite institutions is not a huge surprise: only 6% of our sample initially enrolled at an institution defined as the most selective, so the probability of admission to these schools is incredibly low across the board. Since most students never transferred at all, the number who could feasibly transfer to an elite school would be miniscule in comparison to the amount who initially enroll at these institutions. Indeed, many elite colleges and universities have historically admitted few transfer students from community colleges or elsewhere (Dowd et al., 2006; Wang, 2016). For instance, Princeton University instituted a moratorium on transfer in 1990 and only recently reinstated the opportunity for a very small number of students (Hotchkiss, 2018). On the contrary, it makes sense that we would find higher rates of transfer to highly selective colleges and universities instead. So, while our findings support the hypothesis that upper-SES students employ transfer as an adaptive strategy to access institutions higher in quality, it seems that transfer to the most exclusive colleges and universities is a rare occurrence; and instead, the more common transfer destinations are slightly less selective, yet still well-renowned institutions.

Our findings also suggest that the motivations for lateral transfer may be strategic, at least in part. Although our analysis did not explicitly analyze data pertaining to students’ expressed reasons for transferring, high-SES and upper-middle-SES students had a higher probability of transferring “up” to a college more competitive than their initial institution. Implied in the difference between SES groups in the ascending transfer movement is that students from higher-socioeconomic groups are more inclined to engage in this prestige-seeking behavior, possibly as an adaptive strategy due to exclusion from selective colleges (Alon, 2009).

Notably, there was generally not a difference in ascending transfer behavior by SES among all college students as the relationship was only statistically significant after controlling for the selectivity of students’ first institution. As such, compared to low-SES students, advantaged students only had a higher probability of engaging in ascending transfer behavior when they first enrolled at an institution that was already quite competitive. In other words, upper-middle-SES and high-SES students are not simply interested in moving to another good school with equal social standing; on the contrary, their revisited college choice is more likely to be an institution more selective than their first, on average. In this, it is evident that transfer functions to effectively expand inequality as students from advantaged backgrounds, who are already more likely to first enroll in top schools, further exert their privilege by strategically overcoming their initial exclusion from these institutions.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Changes to admissions-related policies and practice are important to consider as the findings from this investigation complicates our understanding of how higher education evolves to further stratify groups. Notably, lateral transfer may be further exacerbated by the prestige-seeking behaviors of colleges and universities. Rankings such as the U.S. News and World Report (USNWR) have been a significant influence as institutions seek higher positioning on the annual listings. In particular, the USNWR ranking has accounted for several criteria indicating the extent of admissions selectivity. But because only first-year students are used as criteria for this methodology, institutions have the option to use transfer as a pathway to admit students with credentials that may not warrant admission against a larger pool of qualified applicants. Indeed, Golden (2010) shows that admissions offices often encourage potential legacies and students from wealthy families to transfer when they are initially denied. Through such enrollment practices, selective colleges and universities may help to further privilege the most advantaged students.

Given enrollment trends, we argue that it is imperative for selective institutions to consider whether lateral transfer pathways may stymie efforts to improve socioeconomic diversity in their undergraduate student bodies. Our findings suggest that upper-middle- and high-SES students are most likely to move to highly selective colleges and universities, which consists of more public research universities and flagships. This trend also corresponds with the “snowballing” effect observed by scholars who have reported on the enrollment shifts of more affluent students to public flagships (Bowen et al., 2009; Contreras, 2005). Although these selective institutions have a mission to serve the public good as potential “engines of opportunity” (Bowen et al., 2005), higher rates of lateral transfer from advantaged students only furthers the argument that their admissions practices have perpetuated their role as “engines of inequality” (Gerald & Haycock, 2006).

Selective public institutions should recommit themselves, instead, to expand transfer opportunities for students from the least advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. The most likely pathway to achieve this aim, however, would be through the promotion of vertical transfer from community colleges, which have historically served more students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds (Bailey et al., 2015). For instance, in their recent 2030 Capacity Plan, the University of California system has recently announced their intentions to improve the transfer pipeline by increasing the recruitment and enrollment of these students (UC Council of Chancellors, 2022). Other states should consider how their flagship and research universities could follow suit to offer more robust initiatives centering vertical transfer. Moreover, public colleges and universities have traditionally created transfer pathways for community college students through established articulation agreements (Roksa, 2009), and there is a growing body of research showing that these statewide agreements can effectively improve rates of transfer and post-transfer outcomes (Boatman & Soliz, 2018; Worsham et al., 2021). Through such efforts, selective, public institutions can use their resources to eliminate admissions barriers for many low-SES students and work towards advancing more equitable transfer outcomes.

Conclusion

Our study raises several important considerations for future research as there is still very little known about the motivations and outcomes related to nonlinear transfer behavior. Despite a robust body of literature about the choice of students’ first enrolled institution, we have little insight regarding the decision to transfer from four-year colleges and universities, by comparison. One potential area for future research is the consideration of undermatching, or rather, the phenomena in which high-achieving students initially enroll in nonselective colleges where the average achievement level of the student body is not commensurate with their own. Though the present study controlled for several measures of academic achievement, we did not explicitly account for undermatching. Therefore, it is possible that students may have transferred if they were initially academically undermatched with their initial institution, which research shows is especially common among high-achieving students from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds (Bowen et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2013).

Furthermore, although some studies have examined the subsequent success of students who engage in nonlinear transfer (Andrews et al., 2014; Li, 2010; Kalogrides & Grodksy, 2011; Spencer, 2021), more research is needed to understand how these behaviors may result in heterogeneous postsecondary outcomes by socioeconomic background. Because lateral transfer serves as a pathway for the elite to access more selective institutions, it likely functions as a mechanism to further stratify differences in persistence, degree attainment, and labor market outcomes. Future work should consider the implications of these varied enrollment behaviors in contemporary student college-going.

But whether or not socially and economically privileged students will continue to use transfer as a strategic advantage for admission to selective colleges and universities remains unclear. Indeed, much has changed in the college admissions landscape since 2003–2004 when the students in our sample first enrolled in higher education. As of Fall 2021, overall undergraduate college enrollments decreased by 6.5% over two years—a trend that was precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic and related economic downturn (Sedmak, 2021). The National Student Clearinghouse reports that rates of lateral and reverse transfer have also substantially declined (Bobbitt et al., 2021). But in contrast to the general trend, data from the Common App show that selective institutions have seen an increase in application volume during the same period, which includes many students from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds, due in part to the nearly ubiquitous adoption of test-optional policies (Jaschik, 2021).

While no longer requiring the SAT or the ACT for admission may help to democratize access to these schools, some research shows that when colleges elevate extracurricular activities and subjective factors (e.g., essays, etc.), they may also enroll a lower percentage of students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Rosinger et al., 2020). In other words, admissions practices may further evolve to maintain privileges for students from the most advantaged families. Certainly, as evidenced by the increased number of applications to these schools, demand for selective colleges and universities has not waned—even as most colleges and universities have been left reeling from the sudden decline in enrollment. For this reason, researchers should pay attention to the potential ways in which students from higher-socioeconomic groups may continue to strategically adapt in the effort to maintain admissions advantages through transfer or other means.

Change history

21 March 2023

The corresponding author name "George Spencer" was included incorrectly as article subtitle. It is now corrected.

References

Alon, S. (2009). The evolution of class inequality in higher education: competition, exclusion, and adaptation. American Sociological Review, 74(5), 731–755.

Alon, S., & Tienda, M. (2007). Diversity, opportunity, and the shifting meritocracy in higher education. American Sociological Review, 72, 487–511.

Andrews, R., Li, J., & Lovenheim, M. F. (2014). Heterogeneous paths through college: detailed patterns and relationships with graduation and earnings. Economics of Education Review, 42, 93–108.

Avery, C., Glickman, M., Hoxby, C., & Metrick, A. (2004). A revealed preference ranking of U.S. colleges and universities. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper 10803.

Bailey, T., Jaggars, S., & Jenkins, D. (2015). Redesigning America’s community colleges: a clearer path to student success. Harvard University Press.

Bastedo, M. N., & Flaster, A. (2014). Conceptual and methodological problems in research on college undermatch.Educational Reseracher, 43(2).

Bastedo, M. N., & Jaquette, O. (2011). Running in place: low-income students and the dynamics of higher education stratification. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(3), 318–339.

Boatman, A., & Soliz, A. (2018). Statewide transfer policies and community college student success. Education Finance and Policy, 13(4), 449–483.

Bobbitt, R., Causey, J., Kim, H., Lang, R., Ryu, M., & Shapiro, D. (Aug 2021), COVID-19 Transfer, Mobility, and Progress, Academic Year 2020–2021 Report, Herndon, VA:National Student Clearinghouse Research Center

Bound, J., Hershbein, B., & Long, B. T. (2009). Playing the admissions game: student reactions to increasing college competition. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(4), 119–146.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook for Theory and Research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (2nd edition). London: Sage Publications.

Bowen, W. G., Kurzweil, M. A., Tobin, E. M., & Pichler, S. C. (2005). Equity and excellence in American higher education. University of Virginia Press.

Bowen, W. G., Chingos, M. M., & McPherson, M. S. (2009). Crossing the finish line: completing college at America’s public universities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bozick, R. (2007). Making it through the first year of college: the role of students’ economic resources, employment, and living arrangements. Sociology of Education, 80(3), 261–285.

Brewer, D. J., Eide, E. R., & Ehrenberg, R. G. (1999). Does it pay to attend an elite private college? Cross-cohort evidence on the effects of college type on earnings. Journal of Human Resources, 34(1), 104–123.

Calcagno, J. C., Crosta, P., Bailey, T., & Jenkins, D. (2007). Does age of entrance affect community college completion probabilities? Evidence from a discrete-time hazard model. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 29(3), 218–235.

Carnevale, A. P., & Rose, S. J. (2004). Socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and selective college admissions. In R. D. Kahlenberg (Ed.), America’s untapped resource: Lowincome students in higher education (pp. 101–156). Washington, DC: Century Foundation Press.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Saez, E., Turner, N., & Yagan, D. (2017). Mobility report cards: The role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. NBER Working Paper No. 23618. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23618/w23618.pdf

Cipollone, K., & Stich, A. E. (2017). Shadow capital: the democratization of college preparatory education. Sociology of Education, 90(4), 333–354.

Clark, B. (1960). The cooling-out function in higher education. American Journal of Sociology, 65, 569–576.

Cohodes, S., & Goodman, J. (2014). Merit aid, college quality, and college completion: Massachusetts’ Adams scholarship as an in-kind subsidy. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(4), 251–285.

Contreras, F. E. (2005). The reconstruction of merit post-proposition 209. Educational Policy, 19(2), 371–395.

Crisp, G., Potter, C., & Taggart, A. (2021). Characteristics and predictors of transfer and withdrawal among students who begin college at bachelor’s granting institutions. Research in Higher Education.

Dale, S. B., & Krueger, A. B. (2002). Estimating the payoff to attending a more selective college: an application of selection on observables and unobservables. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1491–1527.

Davies, S., & Guppy, N. (1997). Fields of study, college selectivity, and student inequalities in higher education. Social Forces, 75(4), 1417–1438.

Deil-Amen, R., & Tevis, T. L. (2010). Circumscribed agency: the relevance of standardized college entrance exams for low SES high school students. The Review of Higher Education, 33(2), 141–175.

Dowd, A. C., Bensimon, E. M., Gabbard, G., Singleton, S., Macias, E., Dee, J. R., & Giles, D. (2006). Transfer access to Elite colleges and universities in the United States: threading the needle of the american dream. Boston, MA and Los Angeles, CA: University of Massachusetts Boston and University of Southern California.

Espinosa, L. L., Crandall, J. R., & Tukibayeva, M. (2014). Rankings, Institutional Behavior, and College and University Choice: framing the national dialogue on Obama’s ratings Plan. Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education.

Gerald, D., & Haycock, K. (2006). Engines of Inequality. Washington, D.C.: The Education Trust.

Golden, D. (2010). An Analytic Survey of Legacy Preference. In R. D. Kahlenberg (Ed.), Affirmative action for the Rich: legacy preferences in College admissions (pp. 71–99). New York: Century Foundation Press.

Goldrick-Rab, S. (2006). Following their every move: an investigation of social-class difference in college pathways. Sociology of Education, 79(2), 61–79.

Goldrick-Rab, S. (2016). Paying the price: College costs, financial aid, and the betrayal of the american dream. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Goldrick-Rab, S., & Pfeffer, F. T. (2009). Beyond access: explaining socioeconomic differences in college transfer. Sociology of Education, 82(2), 101–125.

Hamilton, L., Roksa, J., & Nielsen, K. (2018). Providing a ‘‘leg up’’: Parental involvement and opportunity hoarding in college.Sociology of Education,111–131.

Hearn, J. C. (1984). The relative roles of academic, ascribed, and socioeconomic characteristics in college destinations. Sociology of Education, 57, 22–30.

Hearn, J. C. (1991). Academic and nonacademic influences on the college destinations of 1980 high school graduates. Sociology of Education, 64, 158–171.

Hoekstra, M. (2009). The effect of attending the flagship state university on earnings: a discontinuity-based approach. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(4), 717–724.

Hotchkiss, M. (2018). Princeton Offers Admission to 13 Students in Reinstated Transfer Program. Princeton University, Office of Communications. Retrieved from https://www.princeton.edu/news/2018/05/09/princeton-offers-admission-13-students-reinstated-transfer-program

Hout, M. (2012). Social and economic returns to college education in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 379–400.

Hoxby, C. (2009). The changing selectivity of american colleges and universities: its implications for students, resources, and tuition. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(4), 95–118.

Hurwitz, M., & Kumar, A. (2015). Supply and demand in the Higher Education Market: College Admission and College Choice. New York, NY: College Board.

Ishitani, T. T., & Flood, L. D. (2018). Student transfer-out behavior at four-year institutions. Research in Higher Education, 59(7), 825–846.

Jaschik, S. (2021, March 15). The rich get richer… Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2021/03/15/new-common-app-data-show-admissions-rich-get-richer

Jack, A. A. (2016). No) harm in asking: class, acquired cultural capital, and academic engagement at an elite university. Sociology of Education, 89(1), 1–19.

Kalogrides, D., & Grodsky, E. (2011). Something to fall back on: Community colleges as a safety net. Social Forces, 89(3), 853–877.

Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods: class, race, and family life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lareau, A., & Weininger, E. B. (2008). Class and the transition to adulthood. In A. Lareau, & D. Conley (Eds.), Social Class: how does it work? (pp. 118–151). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Li, D. (2010). They need help: transfer students from four-year to four-year institutions. The Review of Higher Education, 33(2), 207–238.

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642–1690.

McDonough, P. M., Korn, J., & Yamasaki, E. (1997). Access, equity, and the privatization of college counseling. The Review of Higher Education, 20(3), 297–317.

Raftery, A. E., & Hout, M. (1993). Maximally maintained inequality: expansion, reform, and opportunity in irish education, 1921–75. Sociology of Education, 66(1), 41–62.

Roksa, J. (2009). Building bridges for student success: are higher education articulation policies effective? Teachers College Record, 111(10), 2444–2478.

Roksa, J., Grodsky, E., Arum, R., & Gamoran, A. (2007). Chapter 7: changes in higher education and social stratification in the United States. In Y. Shavit, R. Arum, & A. Gamoran (Eds.), Stratification in higher education: a comparative study (pp. 165–191). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Rosenbaum, J. E., Deil-Amen, R., & Person, A. E. (2006). After admission. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Rosinger, K. O., Ford, K. S., & Choi, J. (2020). The role of selective college admissions criteria in interrupting or reproducing racial and economic inequities. The Journal of Higher Education, 92(1), 31–55.

Sedmak, T., & National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2021, October 26). Undergraduate enrollment declines show no signs of recovery from 2020. Herndon, VA:. Retrieved from https://www.studentclearinghouse.org/blog/undergraduate-enrollment-declines-show-no-signs-of-recovery-from-2020/

Schmitt, C. (2009). Documentation for the restricted-use NCES-Barron’s Admissions Competitiveness: Index Data Files: 1972, 1982, 1992, 2004, and 2008. (NCES 2010–330). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences. U.S. Department of Education. Washington, D.C.

Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Huie, F., Wakhungu, P. K., Bhimdiwali, A., Nathan, A., & Youngsik, H. (2018). Transfer and mobility: a national view of student movement in postsecondary institutions, fall 2011. Cohort signature report No. 15. Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Spencer, G. (2021). Off the beaten path: can statewide articulation support students transferring in nonlinear directions? American Educational Research Journal, 58(5), 1070–1101.

Smith, J., Pender, M., & Howell, J. S. (2013). The full extent of student-college academic undermatch. Economics of Education Review, 32, 247–261.

Turley, R. N. L. (2009). College proximity: Mapping access to opportunity. Sociology of Education, 82(2), 126–146.

University of California Council of Chancellors (2022). University of California 2030 Capacity Plan. Retrieved from https://ucop.edu/institutional-research-academic-planning/_files/uc-2030-capacity-plan.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Poverty guidelines. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines

Wang, X. (2016). A multilevel analysis of community college students’ transfer to four-year institutions of varying selectivity. Teachers College Record, 118, 1–44.

Weis, L., Cipollone, K., & Stich, A. (2015). Poverty, privilege, and the intensification of inequalities in the postsecondary admissions process. In W. Tierney (Ed.), Rethinking education and poverty. Johns Hopkins Press.

Wolniak, G. C., Wells, R. S., Engberg, M. E., & Manly, C. A. (2016). College enhancement strategies and socioeconomic inequality. Research in Higher Education, 57, 310–334.

Worsham, R., DeSantis, A. L., Whatley, M., Johnson, K. R., & Jaeger, A. J. (2021). Early effects of North Carolina’s comprehensive articulation agreement on credit accumulation among community college transfer students. Research in Higher Education.

Zarifa, D. (2012). Higher education expansion, social background and college selectivity in the United States. International Journal of the Sociology of Education, 1(3), 263–291.

Zarifa, D., Kim, J., Seward, B., & Walters, D. (2018). What’s taking you so long? Examining the effects of social class on completing a bachelor’s degree in four years. Sociology of Education, 91(4), 209–322.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to members of the Sociology of Education Association for their constructive feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript presented at the conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Spencer, G., Stich, A. College Choice Revisited: Socioeconomic Differences in College Transfer Destinations Among Four-Year College Entrants. Res High Educ 64, 959–986 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-023-09730-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-023-09730-1