Abstract

We examine the relationship between CEO tenure and audit fees. After controlling for client and auditor attributes in the analyses, we find that audit fees are higher in the initial 3 years of CEOs’ service, suggesting that CEOs in their early career are more likely to show high risk-taking behavior and manage earnings that increases the probability of financial misreporting. Auditors incorporate this risk in their audit pricing decisions resulting in higher audit fees. We also find that audit fees are higher in the final year of CEOs’ service, supporting the argument for departing CEOs’ horizon problem that CEOs in their final year are more likely to manage earnings, and auditors perceive this action as increasing reporting risk in their audit pricing decisions, resulting in higher audit fees. However, the firms with more effective audit committees pay relatively lower audit fees in initial years of CEOs’ service indicating that effective audit committees reduce auditors’ assessed risk during this time-period resulting in lower audit fees. We do not find any evidence on the effect of firms’ CFO power and corporate social responsibility performance on audit fees in these two time-periods of CEOs’ service. The main results hold in a battery of supplemental tests that include the effect of several CEO characteristics, client bargaining power and the effect of SOX. Our study extends CEO characteristics and audit fee literature, and have implications for auditors in their client acceptance and audit pricing decisions, and for regulators to identify the filers with higher financial reporting and audit engagement risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data are obtained from public sources as described in the paper.

Notes

Each CEO brings a unique management style that has repercussions on financial reporting decisions (Bills et al. 2017). Prior research provides evidence on executive-level influence over financial reporting quality (Bertrand and Schoar 2003; Ge et al. 2011) and that earnings quality is directly impacted by managerial ability (Demerjian et al. 2013) and managerial incentives (Beneish 1999; Burns and Kedia 2006; Erickson et al. 2006).

Simunic and Stein (1996) suggest that total audit costs include a “resource cost and an expected liability loss component.” Resource cost increases with an increase in audit effort, and the proportion of liability loss component (ex-ante risk premium) increases with an increase in probable ex-post litigation loss liability that may arise due to undetected material misstatements. In the audit planning stage, auditors assess the probability of misstatements contained in a client’s financial statements and the effectiveness of internal control in the financial accounting process to prevent or detect such misstatements and then adjust the audit procedures to minimize the overall audit risk. Audit risk is a function of inherent risk of material misstatements, control risk that a client’s internal control system may not prevent or detect such misstatements on a timely basis, and detection risk that auditors will fail to detect the misstatements with their audit procedures. The greater the inherent risk, ceteris paribus, the more resources the auditor will have to engage in an audit to reduce the detection risk and, therefore, the audit risk to an acceptable level (Gul and Tsui 1998). Auditors respond to higher audit risk by investing more in audit process and assign more experienced professional staff to a particular engagement, leading to greater audit investment and higher audit fees. In addition, in the face of high audit risk, auditors may also include a risk premium in the quoted fees to cover future litigation loss liability that may arise from undetected financial misstatements during audits.

Our study is different from Bills, Lisic and Seidel (2017) who examine the effect of CEO succession and succession planning on financial reporting risk and audit fees. They show that though new CEOs increase the perception of risk and uncertainty in financial reporting resulting in higher audit fees, careful CEO succession planning (heir apparent) attenuates risk perception as evident from the lack of audit pricing adjustment. In contrast, we investigate the impact of a career cycle of CEO on audit fees in two separate regimes of current CEOs, i.e., their early service period of 3 years and final service year, and also examine how this relationship is impacted by CFO power, CSR and audit committee effectiveness. Furthermore, from audit pricing perspective, our study provides additional insight into the observations of Ali and Zhang (2015) for these two time-periods that are associated with higher probability of financial misstatements and thus, higher reporting risk.

Some prior studies find little/no evidence on the association between managers’ horizon problems and accrual and real earnings management. For instance, Wells (2002) finds little evidence of income-increasing earnings management before CEO turnover and Cheng (2004) finds no association between CEO turnover and R&D expenditures. However, we argue that auditors are more likely to pay attention to potential income-increasing incentive of CEOs in their last year and exert more efforts to identify accounting misstatements of those firms.

The industry dummies are for the following two-digit SIC codes: 01–14, 15–19, 20–21, 22–23, 24–27, 28–32, 33–34, 35–39, 40–48, 49, 50–52, 53–59, and 70–79.

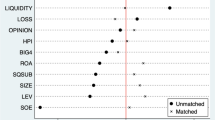

We find that all Spearman correlations among the independent variables are below 0.5 (not tabulated). Moreover, the variance inflation factors in the regressions are less than 3. Thus, multicollinearity has no consequential effect on our primary results.

We do not rule out the possibility that the results for the early years of CEOs’ service could partly be attributed to the transition period of a new executive. The new CEOs might change reporting style, structure of financial reporting, disaggregation of financials or any number of items, which would prompt incumbent auditors to increase the level of their audit testing from prior years to deal with those changes. The situation is likely to increase audit efforts and audit fees.

Prior research provides evidence of earnings management in the departing CEOs’ final two years (Reitenga and Tearney 2003). Thus, we construct a dummy variable of 1 if the firm-year observations correspond to the final 2 years prior to CEOs’ service and re-estimate the regressions. Regression results with the final 2 years included as a test variable are qualitatively similar to our main findings using only the final year as the test variable. Furthermore, we rerun all primary tests using firm fixed effect model and obtained qualitatively similar results.

CFOPOWER is constructed based on CFOs’ continuous years of service in a firm, and is a dummy variable of 1 for firms with CFO tenure in the top quartile, and 0 otherwise.

As a robustness check, we further evaluate the effect of relative CEO–CFO power on the three measures of CEO tenure using the methods adopted by Beck and Mauldin (2014) who evaluate CFO-audit committee relative power in their study. Based on the relative quartiles of CEO and CFO tenure, our variable of interest is constructed as RELATIVE_CEO_CFO, where value ranges from − 3 to + 3. Positive values indicate higher CEO power relative to CFO and negative values indicate lower CEO power relative to CFO. The untabulated results show insignificant interactions of the relative power variable with ETENURE1 and ETENURE2, and insignificant interaction of the variable with LTENURE (though it is significant in one-tailed test). Overall, the results are consistent with those reported in Table 4.

We do not exclude the possibility that lower CSR performance would elevate higher financial reporting risk and audit risk in CEOs' early and late tenure. However, we argue that auditors are more likely to consider CSR firms' genuine commitment to financial statement verification and are less likely to incorporate lower CSR performance in their risk assessments.

As a robustness check, we replace CSR with Hi-Strength variable, which is a dummy variable of 1 if the CSR strength is greater than industry median, and 0 otherwise and re-estimate regressions. The results are similar to the ones with CSR variable.

BoardEx dataset provides biographical information for all members of board and its sub-committees including audit committee and senior executives around the globe. The biographical information includes, but is not limited to, age, gender, nationality, role and functional expertise. Because BoardEx tracks individual members over years, we collapsed the data down to company-year level in order to understand unique characteristics not only of each audit committee member, but also of the audit committee itself.

BoardEx defines functional expertise of audit committee members as prior employment experience relevant to the audit committee [e.g., a public auditor at one of the 25 audit firms listed in Compustat, as a CPA or Chartered Accountant, or in an accounting-specific position, such as Chief Financial Officer, Treasurer, Controller, or Head of Accounting, see Ege (2015)] that individual members sit on.

Given that ACMONITORING by construction could be open to criticism because of underlying notion of a linearity effect by summing three measures for audit committee characteristics, we do a principal component factor analysis on the three measures to form a single "factor" and re-estimate our interaction models by replacing ACMONITORING with this factor. We find that the results remain unchanged.

As the board of directors is the paramount governance mechanism, following Carcello et al. (2002), we additionally control for board characteristics such as board size (BSIZE) and the proportion of independent directors on board (BINDEPENDENCE). Consistent with prior findings (Carcello et al. 2002; Abbott et al. 2003), we find that board size (BSIZE) and the proportion of independent directors on board (BINDEPENDENCE) exhibit positive relationship with audit fees, reinforcing the fact that board quality also matters in auditor’s pricing decision.

Following Cohen et al. (2014), we limit our data beginning in 2001 since the BoardEx database coverage prior to that year is very sparse.

When we partition the sample into two groups based on audit committee size (AC_SIZE) and audit committee functional expertise (AC_EXPERT), the positive effects of all three measures of CEO tenure on audit fees are found only in a group where audit committee size is smaller and audit committee functional expertise is weak. When the sample is partitioned into two groups based on audit committee independence (AC_INDEP), the positive effects of two CEO measures (ETENURE1 and ETENURE2) on audit fees are found only in a group where independent audit committee members are smaller in number.

References

Abbott LJ, Parker S, Peters G, Raghunandan K (2003) The association between audit committee characteristics and audit fees. Audit J Pract Theory 22(2):17–32

Adams RB, Almeida H, Ferreira D (2005) Powerful CEOs and their impact on corporate governance. Rev Financ Stud 18(4):1403–1432

Ali A, Zhang W (2015) CEO tenure and earnings management. J Account Econ 59(1):60–79

Anita M, Pantzalis C, Parl JC (2010) CEO decision horizon and firm performance: An empirical investigation. J Corp Financ 16(3):288–301

Ashbaugh H, LaFond R, Mayhew BW (2003) Do nonaudit services compromise auditor independence? Further evidence. Account Rev 78(3):611–639

Axelson U, Bond P (2012) Wall street occupations. J Finance 70(5):1949–1996

Baker TA, Lopez TJ, Reitenga AL, Ruch GW (2019) The influence of CEO and CFO power on accruals and real earnings management. Rev Quant Finance Account 52:325–345

Barua A, Davidson LF, Rama DV, Thiruvadi S (2010) CFO gender and accruals quality. Account Horiz 24(1):25–39

Beck MJ, Mauldin EG (2014) Who’s really in charge? Audit committee versus CFO power and audit fees. Account Rev 89(6):2057–2085

Beneish BD (1999) Incentives and penalties related to earnings overstatements that violate GAAP. Account Rev 74(4):425–457

Berns VDK, Klarner P (2017) A review of the CEO succession literature and a future research program. Acad Manag Perspect 31(2):83–108

Bertrand M, Schoar A (2003) Managing with style: the effect of managers on firm policies. Q J Econ 118(4):1169–1208

Billings BA, Gao X, Jia Y (2014) CEO and CFO equity incentives and the pricing of audit services. Audit J Pract Theory 33(2):1–25

Bills KL, Lisic LL, Seidel TA (2017) Do CEO succession and succession planning affect stakeholders’ perceptions of financial reporting risk? Evidence from audit fees. Account Rev 92(4):27–52

Brickley J, Linck J, Coles J (1999) What happens to CEOs after they retire? New evidence on career concerns, horizon problems, and CEO incentives. J Financ Econ 52(3):341–377

Burks J (2010) Disciplinary measures in response to restatements after Sarbanes-Oxley. J Accout Public Policy 29(3): 195–225

Burns N, Kedia S (2006) The impact of performance-based compensation on misreporting. J Financ Econ 79(1):35–67

Carcello J, Hermanson T, Neal L, Riley R (2002) Board characteristics and audit fees. Contemp Account Res 19(3):365–384

Carroll A (1979) A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad Manag Rev 4(4):497–505

Casterella J, Francis J, Lewis B, Walker P (2004) Auditor industry specialization, client bargaining power, and audit pricing. Audit J Pract Theory 23(1):123–141

Chan AMY, Liu G, Sun J (2013) Independent audit committee members’ board tenure and audit fees. Account Finance 53(4):1129–1147

Chava S, Purnanadam A (2010) CEOs versus CFOs: Incentives and corporate policies. J Financ Econ 97(2):263–278

Chen Y, Gul FA, Veeraraghavan M, Zolotoy L (2015) Executive equity risk-taking incentives and audit pricing. Account Rev 90(6):2205–2234

Chen L, Srinidhi B, Tsang A, Yu W (2016) Audited financial reporting and voluntary disclosure of corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports. J Manag Account Res 28(2):53–76

Chen W, Zhou G, Zhu X (2019) CEO tenure and corporate social responsibility performance. J Bus Res 95:292–302

Cheng S (2004) R&D expenditures and CEO compensation. Account Rev 79(2):305–328

Choi A, Sohn B, Yeun D (2018) Do auditors care about real earnings management in their audit fee decisions? Asia Pac J Account Econ 25(1–2):21–41

Cohen J, Hoitash U, Krishnamoorthy G, Wright A (2014) The effect of audit committee industry expertise on monitoring the financial reporting process. Account Rev 89(1):243–273

Coles J, Daniel N, Naveen L (2006) Managerial incentives and risk-taking. J Financ Econ 79(2):431–468

Combs JG, Ketchen DJ Jr, Perryman AA, Donahue MS (2007) The moderating effect of CEO power on the board composition-firm performance relationship. J Manag Stud 44(8):1300–1323

Core J, Guay W (2002) Estimating the value of stock option portfolios and their sensitivities to price and volatility. J Account Res 40(3):613–630

Demerjian P, Lev B, McVay S (2012) Quantifying managerial ability: a new measure and validity tests. Manag Sci 58(7):1229–1274

Demerjian P, Lev B, Lewis M, McVay S (2013) Managerial ability and earning quality. Account Rev 88(2):463–498

Demers E, Wang C (2010) The impact of CEO career concern on accruals based and real earnings management. Working paper, INSEAD

Dhaliwal DS, Li OZ, Tsang A, Yang YG (2011) Voluntary non-financial information and cost of equity capital: the initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Account Rev 86(1):59–1000

Dhaliwal DS, Radhakrishnan S, Tsang A, Yang YG (2012) Non-financial disclosure and analysts forecast accuracy: international evidence on corporate social responsibility disclosure. Account Rev 87(3):723–759

Ege MS (2015) Does internal audit function quality deter management misconduct? Account Rev 90(2):495–527

Erickson M, Hanlon M, Maydew E (2006) Is there a link between executive compensation and accounting fraud? J Account Res 44(1):113–143

Faccio M, Marchica M, Mura R (2016) CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation. J Corp Finance 39(August):193–209

Fama EF (1980) Agency problems and the theory of the firm. J Polit Econ 88(2):288–307

Fee CE, Hadlock CJ (2003) Raids, rewards, and reputations in the market for managerial talent. Rev Financ Stud 16(4):1315–1357

Feng M, Ge W, Luo S, Shevlin T (2011) Why do CFOs became involved in material accounting manipulations? J Account Econ 51(1–2):21–36

Francis JR, Reichelt K, Wang D (2005) The pricing of national and city-specific reputations for industry expertise in the U.S. audit market. Account Rev 80(1):113–136

Francis B, Hasan I, Park JC, Wu Q (2015) Gender differences in financial reporting decision making: evidence from accounting conservatism. Contemp Account Res 32(3):1285–1318

Friedman H (2014) Implications of power: When the CEO can pressure the CFO to bias reports. J Account Econ 58(1):117–141

Fritzche DJ (1991) A model of decision making incorporating ethical values. J Bus Ethics 10(11):841–852

Ge W, Matsumoto D, Zhang J (2011) Do CFOs have style? An empirical investigation of the effect of individual CFOs on accounting practices. Contemp Account Res 28(4):1141–1179

Geiger MA, North DS (2006) Does hiring a new CFO change things? An investigation of changes in discretionary accruals. Account Rev 81(4):781–809

Geiger MA, Taylor P (2003) CEO and CFO certifications of financial information. Account Horiz 17(4):357–368

Gow ID, Ormazabal G, Taylor DJ (2010) Correcting for cross-sectional and time-series dependence on accounting research. Account Rev 85(2):483–512

Griffin P, Sun Y (2013) Going green: market reaction to CSR wire news releases. J Account Public Policy 32(2):93–113

Gul FA, Tsui JSL (1998) A test of the free cash flow and debt monitoring hypotheses: evidence from audit pricing. J Account Econ 24:219–237

Gul FA, Chen CJP, Tsui JSL (2003) Discretionary accounting accruals, managers’ incentives and audit fees. Contemp Account Res 20(3):441–464

Hambrick DC, Fukutomi GDS (1991) The seasons of a CEO’s tenure. Aca Manag Rev 16:719–742

Hay DC, Knechel WR, Wong N (2006) Audit fees: a meta-analysis of the effect of supply and demand attributes. Contemp Account Res 23(1):141–191

Hemingway CA, Maclagan PW (2004) Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics 50(1):33–44

Hermalin B, Weisbach M (1998) Endogenously chosen boards of directors and their monitoring of the CEO. Am Econ Rev 88:96–118

Himmelberg CP, Hubbard RG, Palia D (1999) Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance. J Finance Econ 53(3):353–384

Hennes KM, Leone AJ, Miller BP (2008) The importance of distinguishing errors from irregularities in restatement research: the case of restatements and CEO/CFO turnover. Account Rev 83(6):1487–1519

Ho SSM, Li AY, Tam K, Zhang F (2015) CEO gender, ethical leadership, and accounting conservatism. J Bus Ethics 127(2):351–370

Hohenfels D (2016) Auditor tenure and perceived earnings quality. Int J Audit 20(3):224–238

Holmstorm B (1982) Moral hazard in teams. Bell J Econ 13(2):324–340

Holmstorm B (1999) Managerial incentive problems: a dynamic perspective. Rev Econ Stud 66(1):169–182

Huang J, Kisgen DJ (2013) Gender and corporate finance: are male executives overconfident relative to female executives? J Finance Econ 108(3):822–839

Huang H-W, Liu L-L, Raghunandan K, Rama DV (2007) Auditor industry specialization, client bargaining power, and audit fees: further evidence. Audit J Pract Theory 26(1):147–158

Huang H, Parker RJ, Yan YA, Lin Y (2014) CEO turnover and audit pricing. Account Horiz 28(2):297–312

Iliev P (2010) The effect of SOX section 404: costs, earnings quality, and stock prices. J Finance 65(3):1163–1196

Jensen M, Meckling W (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency cost and capital structure. J Finance Econ 3(4):305–360

Jeong N, Kim N, Cullen J (2016) CEO tenure and CSR: Impact of CEO self-interest on long-term investment decision making. Acad Manag Proc 2016(1)

Jiang J, Petroni KR, Wang IY (2010) CFOs and CEOs: Who have the most influence on earnings management? J Financ Econ 96:513–526

Kalyta P (2009) Accounting discretion, horizon problem, and CEO retirement benefits. Account Rev 84(5):1553–1573

Kalyta P, Magnan M (2008) Executive pensions, disclosure quality, and rent extraction. J Account Public Policy 27(2):133–166

Kannan Y, Skantz TR, Higgs JL (2014) The impact of CEO and CFO equity incentives on audit scope and perceived risks as revealed through audit fees. Audit J Pract Theory 33(2):111–139

Kim EH, Lu Y (2011) CEO ownership, external governance and risk taking. J Finance Econ 102(2):272–292

Kim Y, Park MS, Wier B (2012) Is earnings quality associated with corporate social responsibility? Account Rev 87(3):761–796

Kim Y, Li H, Li S (2015) CEO equity incentives and audit fees. Contemp Account Res 32(2):608–638

Kothari SP, Leone AJ, Wasley CE (2005) Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. J Account Econ 39:163–197

Krishnan GV, Visvanathan G (2009) Do auditors price audit committee expertise? The case of accounting versus non-accounting financial experts. J Account Audit Finance 24(1):115–144

Krishnan GV, Wang C (2015) The relation between managerial ability and audit fees and going concern opinions. Audit J Pract Theory 34(3):139–160

McWilliams A, Seigel D, Wright P (2006) Guest editors’ introduction to corporate social responsibility: strategic implications. J Manag Stud 43(1):1–18

Mian S (2001) On the choice and replacement of chief financial officers. J Financ Econ 60(1):143–175

Miller D (1991) Stale in the saddle: CEO tenure and the match between organization and environment. Manag Science 37(1):34–52

Mitra S, Hossain M, Deis D (2007) The empirical relationship between ownership characteristics and audit fees. Rev Quant Finance Account 28:257–285

Mitra S, Jaggi B, Al-Hayale T (2019) Managerial overconfidence, ability, firm-governance and audit fees. Rev Quant Finance Account 52:841–870

Murphy KJ, Zimmerman JL (1993) Financial performance surrounding CEO turnover. J Account Econ 16(1–3):273–315

Oyer P (2008) The making of an investment banker: macroeconomic shocks, career choice and lifetime income. J Finance 63(6):2601–2628

Petrovits CM (2006) Corporate-sponsored foundations and earnings management. J Account Econ 41(3): 335–362

Prendergast C, Stole L (1996) Impetuous youngsters and jaded old-timers: acquiring a reputation for learning. J Political Econ 104(6):1105–1134

Prior D, Surroca J, Trobo, JA (2008) Are socially responsible managers really Ethical? Exploring the relationship between earnings management and corporate social responsibility. Corp Gov- an Intern Rev 16(3):160–177

Reitenga AL, Tearney MG (2003) Mandatory CEO retirements, discretionary accruals, and corporate governance mechanisms. J Account Audit Finance 18(2):255–280

Simunic D, Stein MT (1996) The impact of litigation risk on audit pricing: a review of the economics and the evidence. Audit J Pract Theory 15(Supplement):119–134

Singer Z, You H (2011) The effect of section 404 of the Sarbanes–Oxley act on earnings quality. J Account Audit Finance 26(3):556–589

Tsui JSL, Jaggi B, Gul FA (2001) CEO domination, growth opportunities, and their impact on audit fees. J Account Audit Finance 16(3):189–208

Wells P (2002) Earnings management surrounding CEO changes. Account Finance 42(2):169–193

Wu Q (2017) Managing earnings for my boss? Financial reporting and the balance of power between CEOs and CFOs. Working paper of Baylor University

Wu S, Levitas E, Priem RL (2005) CEO Tenure and Company Invention under Differing Levels of Technological Dynamism. Aca Manag J. 48(5): 859–873

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mitra, S., Song, H., Lee, S.M. et al. CEO tenure and audit pricing. Rev Quant Finan Acc 55, 427–459 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-019-00848-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-019-00848-x