Abstract

In this paper, we provide evidence that banks with a low level of capitalization have reduced their commitment with respect to lines of credit after the introduction of the Basle Accord. A bank's lending behavior reflects its level of commitment towards borrowers, which in turn affects the level of effort it exerts on screening and monitoring the activities of borrowers. We find that the post-Basle Accord market reaction to the announcement of lines of credit issued by banks with a low level of capitalization is significantly lower than the reaction to other types of bank credit announcements. We interpret this result as evidence that some banks have a low level of commitment associated with lines of credit after the Basle Accord.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the United States banks had to gradually implement these requirements starting January 1, 1990 and were expected to fully comply by December 31, 1991.

Prior to the introduction of the Basle Accord, unused lines of credit had no impact on a bank's ability to meet minimum capital requirements.

When the capital ratio of a bank is close to the minimum required level, regulators monitor the bank more closely. To avoid this scrutiny a bank may, for instance, have to issue additional capital or change the composition of its assets.

We use an event study methodology in this paper. We examine the market reaction at the disclosure of bank credit agreements to infer the impact of the Basle Accord on bank lending behavior. Given that the financial press summarizes the credit agreements, we face a data constraint in that we cannot directly observe the introduction of clauses to reduce a bank's level of commitment. Alternatively, it is possible to study banks’ level of commitment by examining the terms of the loans from the 10-K forms which are available several months after the disclosure of the credit agreements.

Liu et al. (1997) define banks that are below (above) the mean total capital ratio as “at risk” (“not at risk”) banks. When we introduce this categorization in the analyses to distinguish between banks with a low or a high level of capitalization we obtain the same conclusions. An alternative test would be to define banks that are under or just at the minimum capital requirement as at risk banks. However, as indicated in Table 1 all of the banks in our sample meet the minimum capital requirements.

Bank data is obtained from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation website.

If a bank wants to change the maturity or terms of their lines of credit, it is possible that borrowers will switch banks. Under this scenario, only the most financially constrained borrowers would be put in this position. We test this possibility by comparing the financial position (e.g., leverage) of firms borrowing from banks with a low level of capitalization to those borrowing from banks with a high level of capitalization and we observe no significant differences between the two groups.

An exhaustive search was conducted using key words to identify all publicly available announcements of bank credit agreements disclosed in the Wall Street Journal. To ensure that all disclosures were identified in the initial search, we used general expressions such as “loan”, “credit”, “financing”, “credit agreement”, “restructuring”, “commitment”, “refinancing”, “credit line”, and “revolving”.

We require at least 100 days of trading in the estimation period in order to calculate expected returns using the market model.

Consistent with Lummer and McConnell (1989) and Best and Zhang (1993), the favorable group includes loans for which one of the following occurred: (1) the maturity of the credit agreement is lengthened; (2) the interest rate is reduced; (3) the amount of the loan is increased; or (4) the debt covenants are made less restrictive. The unfavorable group includes loans for which at least one of the above criteria is revised negatively while no terms are revised positively. The mixed group contains loans having at least one term revised favorably and one term revised unfavorably. A total of 195 revisions were favorable, 16 were unfavorable and 22 were mixed.

Consistent with Billett et al. (1995), when a syndicate of banks is involved we use the descriptive statistics of the lead bank.

The non-members of the FDIC are foreign (i.e., non-US) banks.

We combine announcements of term loans, with announcements involving both a line of credit and a term loan, into one category.

We also estimate Eq. (1) after controlling for firm size. Consistent with the univariate analysis, our results are not affected by the inclusion of a size variable.

The amount of non-performing loans is not included in Eqs. (1) and (2) since the information is not available on the FDIC website for the entire sample period covered by these tests.

An examination of the annual distribution of banks’ capital ratios over our sample period does not reveal any systematic patterns in the average annual values.

Billett et al. (1995) provide evidence that a bank's credit quality conveys information to capital markets. They observe a positive association between the quality of a bank's credit rating and the magnitude of the market reaction to the announcement of a credit agreement. To examine this possibility, we collect the available Moody's credit ratings for our sample banks’ senior non-secured debt. The correlation between the level of bank capitalization and credit ratings is low (−0.27) implying that credit ratings may provide additional explanatory power in our tests. To examine this possibility, we code the Moody's ratings in a manner consistent with Billett et al. (1995) and include a credit rating variable in Eq. (3). The results (not reported) indicate that the credit rating variable is insignificant and its inclusion does not affect our main conclusions from Table 5.

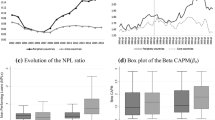

Alternatively, if a bank has a large amount of non-performing loans, it may indicate that the bank's screening and monitoring activities are not effective. As a result, the market may not positively react to the announcement of a credit agreement provided by such a bank. In this case, we would observe a negative sign on NPL. See Liu and Ryan (1995) for a discussion on the signaling role of NPL.

The variable NPL is not included in Tables 6 and 7. Table 6 compares the market reaction to the disclosure of lines of credit before and after the introduction of the Basle Accord. Given that the value of non-performing loans is not available for the entire sample period, we exclude this variable. Table 7 compares term loans (issued by any bank) to lines of credit (issued by a bank with a low level of capitalization and banks with a high level of capitalization). To maximize the number of observations, we do not limit our analysis to the term loans for which the name of the bank is mentioned.

References

Aintablian S, Roberts GS (2000) A note on market response to corporate loan announcements in Canada. J Banking Fin 24:381–393

Andre P, Mathieu R, Zhang P (2001) A note on capital adequacy and the information content of term loans and lines of credit. J Banking Fin 25:431–444

Best R, Zhang H (1993) Alternative information sources and the information content of bank loans. J Fin 48:1507–1522

Billett MT, Flannery MJ, Garfinkel JA (1995) The effect of lender identify on a borrowing firm's equity return. J Fin 50:699–718

Boot AWA (2000) Relationship banking: What do we know. J Fin Intermed 9:7–25

Brown SJ, Warner JB (1980) Measuring security price performance. J Fin Econ 8:205–258

Houston J, James C (1996) Bank information monopolies and the mix of private and public debt claims. J Fin LI:1863–1889

James C (1987) Some evidence of the uniqueness of bank loans. J Fin Econ 19:217–235

Johnson SA (1996) The effect of bank reputation on the value of bank loans agreements. J Acc, Aud Fin 12(1):83–100

Liu CC, Ryan SG (1995) The effect of bank loan portfolio composition on the market reaction to an anticipation of loan loss provisions. J Acc Res 33(1):77–94

Liu CC, Ryan SG, Wahlen JM (1997) Differential valuation implications of loan loss provisions across banks and fiscal quarters. Acc Rev 72(1):133–146

Lummer SL, McConnell JJ (1989) Further evidence on the bank lending process and the capital-market response to bank loan agreements. J Fin Econ 25:99–122

Ongena S, Smith DC (2000) Bank relationships: A review. In: Zenios SA, Harker P (eds) Performance of financial institutions. Cambridge Press

Petersen MA, Rajan RG (1994) The benefits of lending relationships: Evidence from small business data. J Fin 49:3–37

Preece D, Mullineaux DJ (1996) Monitoring, loan renegotiability, and firm value: The role of lending syndicates. J Banking Fin 20:577–593

Rajan RG (1992) Insiders and outsiders: The choice between informed and arm's-length debt. J Fin 47:1367–1400

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Standard Research Grant and from a grant partly funded by Wilfrid Laurier University Operating funds and partly by a SSHRC Institutional Grant awarded to Wilfrid Laurier University. We thank Jean Bedard, Matthew Billet, Daniel Coulombe, Ole-Kristian Hope, Kiridaran Kanagaretnam, Suzanne Paquette and workshop participants at Laval University for their comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, L., Mathieu, R., Robb, S. et al. Bank capitalization and lending behavior after the introduction of the Basle Accord. Rev Quant Finan Acc 28, 147–162 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-006-0009-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-006-0009-4