Abstract

Women’s employment plays an important role in household well-being, and among mothers, lack of child care is one of the main reasons for not working and not seeking employment. We investigate the effect of a reform that lengthened school schedules from half to full days in Chile—providing childcare for school aged children—on different maternal employment outcomes. Using a panel of 2814 mothers over a 7-year period, we find evidence of important positive causal effects of access to full-day schools on mother’s labor force participation, employment, weekly hours worked, and months worked during the year. We also find that lower-education and married mothers benefit most from the policy. Findings suggest that alleviating childcare needs can promote women’s attachment to the labor force, increase household incomes and alleviate poverty and inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Women’s participation in the labor markets plays an important role in household welfare; therefore, policies that promote female labor force participation and employment are central for economic well-being. Motherhood is possibly the most relevant factor affecting a woman’s decision to engage in the labor market, because due to gender roles that are deeply embedded in society, it is often women who suspend their labor force activities when they have children. Recent data reveal that worldwide, 64 percent of married women participate in the labor force before having children, compared to 48 percent once they become mothers; among single women without and with children, participation rates are 82 and 70 percent, respectively (United Nations Women, 2020). The decisions women make after childbirth include whether to enter/continue or exit the labor market, and if so, how much time to dedicate to employment outside the home. In this context, public policies can play a direct or indirect role in reconciling work and family life. Research has estimated that lack of family-friendly employment policies explains almost 30 percent of the decrease in U.S. women’s labor force participation in last decades (Blau & Kahn, 2013), whereas policies such as flexible work schedules have facilitated mothers’ entry or reentry into the labor market after child birth (Chioda et al., 2011; Del Boca, 2002).

Low access to childcare is one of the main reasons cited by mothers of young children for not working or seeking employment. If increased female labor force participation is a desirable objective, policies that improve access to childcare should increase women’s employment. This relationship has been broadly studied in the literature in the context of preschool-aged children. Expansions in the coverage of daycare or preschool centers for children aged 0–4 years has led to increases in mothers’ employment (Berlinski & Galiani, 2007; Berlinski et al., 2011; Baker et al., 2008; Lefebvre & Merrigan, 2008; Brilli et al., 2016), as has access to kindergarten (Gelbach, 2002; Cascio, 2009; Fitzpatrick, 2012; Sall, 2014; and Cannon et al., 2006). Furthermore, the positive impacts of childcare are found to be long-lasting (Barua, 2014).

In addition to the effect of access to childcare for preschool-aged children, recent evidence finds that childcare for school-aged children provided by after-school programs have also had positive effects on mothers’ employment in Switzerland (Felfe et al., 2016) and Chile (Martínez & Perticara, 2017). School schedule extension policies in Mexico and Chile have also led to greater labor supply by mothers (Padilla-Romo & Cabrera-Hernández, 2019; Contreras & Sepúlveda, 2016), as did lowering the mandatory school entry age in Norway (Finseraas et al., 2017), whereas less time in school limits mothers’ labor force participation: shorter schedules lead to lower participation of mothers of elementary school children in Japan (Takaku, 2019), while year-round school calendars in California reduced mothers’ labor force participation, possibly because it made child care arrangements more difficult (Graves, 2013).

In this paper, we study the impact of a nation-wide education reform in Chile that extended the length of school schedules on mothers’ employment outcomes. While most studies to date have focused almost exclusively on mothers’ participation and employment decisions, our data allows us to explore other measures that capture the intensity of work and mothers’ attachment to the labor force, which has received relatively less attention in the literature. This is relevant because in labor markets with inflexible work regimes where part-time work is scarce, such as Chile, women adjust their labor supply by entering and exiting jobs. Another feature of our study is the panel nature of our data, which allows us to estimate a fixed-effects model that controls for (time-invariant) individual preferences regarding fertility, work, or child care arrangements; compared to other studies, our estimated effects of childcare are unbiased under weaker assumptions (i.e., as long as individual’s preferences are time-invariant).

The full-day schedule reform—which we refer to as FDS throughout this paper—may affect mothers’ decisions through different channels. First, the FDS regime is effectively a subsidy for nonfamily child care for school-aged children, which affects the opportunity cost of mothers’ time, and potentially, her employment decisions. A second channel would be through intra-household substitution of labor if the reform were to also affect spouses’ (fathers’) labor supply. Thirdly, access to schools with longer schedules may allow mothers to investment in her own formal education, thereby improving her prospects in the labor market. Our results suggest that the childcare subsidy implicit in the FDS policy is the main driver of the results.

We find that greater access to full-day schools significantly increased mothers’ labor force participation and employment in Chile. An increase in FDS access of 30 percentage points—equivalent to increasing the share of full-day primary schools in our sample to full FDS coverage, i.e., moving from about 70 percent to 100 percent—leads to an increase in mothers’ labor force participation and employment of 9 and 8.1 percent, respectively, and an increase in weekly hours worked of 3 h.Footnote 1 We also find that increasing FDS access to full coverage would increase mothers’ attachment to the labor market: the number of months worked during the year increases by 1 percent, and the likelihood of participating and working for more than 6 months during the year increases by 5 and 2 percent, respectively. Although these effects are modest, they suggest that full-day schedules can lead to more stable employment, since mothers stay in their jobs for longer periods of time. We also find that the effects vary by mothers’ education, and whether she is single: increased access to FDS schools was more beneficial for mothers with lower levels of education, and those with a spouse or partner.

Our results provide evidence that families’ childcare demands persist into a child’s school years, therefore policies aimed at increasing women’s employment need to consider older children, not only preschoolers. Also, they suggest that targeting full-day schooling programs to vulnerable populations, such as those with low-education mothers, would be most effective in promoting women’s labor force participation and more stable employment.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a background review of the Chilean education system and the full-day school reform. Section 3 explains our identification strategy and the estimation methodology. Section 4 describes the data and variables used in our estimates. Section 5 discusses our results and Section 6 presents our conclusions.

2 The full-day school reform and female employment

In 1997, Chile began to implement a national education reform in the public school system that increased weekly hours of instruction without extending the number of school days, which led to longer school schedules.Footnote 2 In primary school—which consists of eight years of education—the reform increased weekly academic hours from 30 to 38 in grades 3 to 6, and from 33 to 38 for 7th and 8th grades. In addition, time allocated for recesses and lunch were extended, so that weekly time spent at school increased by about 1.5 to 2 hours daily. For most schools, the policy meant changing from a system of half-day shifts, to continuous full-day schedules. The reform also increased academic hours of secondary schools, but since childcare is a concern only for mothers of preschool and primary school-aged children, in this paper we only include mothers when their youngest child was in preschool and primary school.Footnote 3

Parents in Chile can choose a publicly subsidized school for their child without geographic restrictions. In our data, we do not observe the specific school chosen by parents, so we study the impact of mothers’ access to FDS schools. The FDS law mandated that all primary (and secondary) schools that receive public funds must offer full-day programs to all their students by 2007 or 2010, depending on the type of school.Footnote 4 The school system is highly decentralized in Chile, so that each school could decide the date to switch to the extended schedule regime and the extent of implementation within the school.Footnote 5 The extended schedules were not mandatory for 1st and 2nd grade, but many schools extended their schedules voluntarily. Finally, the FDS law stipulated that all publicly funded schools created after 1997 must initiate operations as full-day schools.Footnote 6 Ultimately, each schools’ decision depended on their individual infrastructure and financial constraints.Footnote 7 As a result, the phase-in of the reform was gradual, so that families’ access to schools with longer schedules varied in time and across geographic areas. Table 1 summarizes the pace of implementation of the program from the initial year of the reform until 2009. In 1997, the first year of the reform, in most municipalities—62 percent—schools had low take-up rates (below 20%); by 2009, in most municipalities—60 percent—schools reached take-up rates of 70–100 percent. The geographic variation of the policy’s implementation is also presented graphically in Fig. 1.

3 Data and variables

3.1 Data

Our data come from three sources. First, data for individual-level variables, i.e., labor market outcomes and socio–economic characteristics, come from Chile’s Social Protection Survey (Encuesta de Protección Social), which we denominate as EPS for its Spanish acronym. The EPS is the first nationally representative, long-term longitudinal survey implemented in Chile. It collects detailed information of respondent’s current employment situation, as well as information on individuals’ education, health, their household characteristics, and family demographics. Additionally, the EPS collects individuals’ employment history, which allows us to construct traditional employment variables, such as participation and employment decisions (i.e., extensive margins) and hours worked (i.e., intensive margin) with information from longer period of reference than other surveys in Chile, as well as other, less common measures of labor force attachment, such as number of months worked during the year and whether individuals worked at least half of the year.

We use rounds from 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2009 to construct an unbalanced panel of mothers who are potentially affected by the policy.Footnote 8 Since mothers of younger children have a greater demand for childcare, they are more likely to respond to the full-day school policy (see footnote 3); thus, we limit our sample to women that were potentially affected by the policy, i.e., women of working age (18–65) with at least one child aged 13 years or younger in any of the years she was surveyed. Since our data is longitudinal, we can analyze how mothers’ decisions change with changes in exposure to the policy, as well as with changes in her children’s age.

Our second source of information comes from publicly available administrative school data obtained from the Ministry of Education website, which provides the information necessary to construct our policy variable—which is coverage of full day schooling at the municipality level. From this administrative data, we also construct a variable that measures access to preschool (Pre-Kinder and Kindergarten) in the municipality of residence, which we include as a control variable in our estimations. Our third data source is Chile’s national CASEN Household Surveys, publicly available from the Ministry of Family and Social Development, from which we construct municipal level characteristics.Footnote 9

3.2 Variables

3.2.1 Labor market outcomes

The EPS data allows us to construct employment variables that measure both extensive and intensive margins of employment. We construct two variables that measure whether mothers participated in the labor force during the previous year, and whether she held paid employment at any time during the previous year. We also construct a variable of weekly hours worked in the main job during the previous year.

It is important to note that the employment questions in the EPS survey have a longer period of reference—12 months—compared to other employment surveys in Chile, i.e., CASEN household surveys and the National Employment Survey, ENE, which inquire about employment during the previous week. Therefore, though all variables constructed with EPS data are representative of the population, the EPS employment measures are not comparable to other sources because they capture individuals’ labor force activity during a longer period of time. In this regard, the EPS is more reflective of individuals’ employment outcomes throughout a given year relative to CASEN household surveys, which measure activity during the month of the survey.

Furthermore, the EPS surveys provide additional information on the degree of attachment to the labor force, specifically, number of months’ women participated in the labor force and months worked during the previous 12 months. With this information, we also construct variables for share of the year worked, and whether women participated in the labor force and whether they worked for at least 6 of the last 12 months.

3.2.2 Full day schooling

To measure FDS availability at the municipal level, we obtained publicly available administrative school data from the Ministry of Education that contains detailed yearly information on full day enrollment within a school. As discussed above, one feature of the program is that it did not require schools to implement full days for all their grade-levels, they were only required to offer it to all classrooms of the same grade, so that schools could progressively increase their full-day enrollment. In this paper, we define a school as FDS when at least half of its grade levels were under FDS. Our policy variable, therefore, is the share of schools under FDS in a municipality in a given year.Footnote 10

3.2.3 Women’s individual characteristics

In terms of individual characteristics, in our estimations we include measures of years of education and age of the mother. In addition, we also include an indicator variable that is equal to one when the mother’s youngest child is of primary school age, i.e., between 6 and 13 years of age. This latter variable is intended to capture the timing in which the policy should have an effect on mothers’ labor market outcomes.Footnote 11

3.2.4 Municipal-level characteristics

We also control for municipal-level characteristics, including the share of schools with pre-K and kindergarten, the average adult educational attainment measured by average years of education in the adult population (aged 25 and older), municipal poverty rates, unemployment rates (female and male), and labor force participation rates (female and male). In other to control for preexisting trends in labor market outcomes (see Section 4), we control for the initial labor market conditions classifying a municipality as “Low Labor Market Outcome” for three separate outcomes: municipal rates of women´s labor force participation, employment and hours worked. We define a municipality as having a low preexisting outcome, if the outcome was below the median in the year prior to our period of analysis.

The share of schools with pre-K and kindergarten was constructed from administrative school data from the Ministry of Education. All other municipal variables were constructed from Chile’s CASEN Household Surveys, which are representative of most municipalities in Chile during the period. In order to avoid the possibility that our results might be affected by migration decisions correlated with municipal FDS coverage, we exclude women that migrate to a different municipality during the period.Footnote 12

Summary statistics of all variables are found in Table 2. Our sample is an unbalanced panel of 2814 mothers.Footnote 13 Our panel has low attrition rates, and attrition is not systematically correlated to FDS access nor to most observable characteristics.Footnote 14

In our sample, approximately 75 percent of mothers participated in the labor force and 64 percent worked during at least one of the 12 months before the survey.Footnote 15 Mothers worked for an average of 27.2 hours per week, and during 6.1 months, equivalent to 53 percent of the year. Almost 70 percent of mothers in the sample participated in the labor force for more than half of the year, while 54 percent were employed during more than half of the year. Table 2 also reveals that mothers are more likely to work and have stronger attachment to the labor force when their youngest child reaches primary school relative to when the youngest child was of preschool age.

Regarding FDS implementation, mothers in our sample live in a municipality where on average 53 percent of elementary schools offer at least half of their grade levels under the FDS regime.Footnote 16 The differences in FDS coverage increase when mothers’ youngest child gets older, which reflects greater policy take-up through time. Mothers in our sample are 37 years old on average and they have completed 10.5 years of education; mothers of younger children are younger and have about half a year more education than mothers of older children. In our sample, the percentage of observations in which women have their youngest child of primary school age is 65 percent; 68 percent of mothers have a spouse or partner and 26.6 percent being the head of the household.Footnote 17 When we compare women with and without children of primary school age, we observe that when women’s youngest child is of primary school age, fewer mothers have spouses/partners (66 percent versus 72 percent), and they are more likely to be the head of household (30 percent versus 21 percent).

In terms of the municipal characteristics, we find that the average share of schools with pre-K and Kindergarten is 71 percent (with no significant difference by age of the youngest child). Mothers in our sample live in municipalities where the population has about 10 years of education, on average; where the poverty rate is 17 percent; where on average, 41 and 72 percent of women and men participate in the labor force, and where female and male employment rates are 88 and 92 percent, respectively. Regarding initial labor market conditions, about 49 percent of mothers live in municipalities that had low initial female labor force participation in 2000; 53 percent live in municipalities with low initial employment rates in 2000, and 51 percent in municipalities with low hours of work in 2000. We observe no significant differences in municipality characteristics between mothers when their youngest child is in preschool relative to primary school (differences are statistically significant, but their magnitudes are practically zero).

4 Identification and estimation

Our estimates are based on a reduced-form panel data model of female employment outcomes that controls for (time-invariant) individual unobservables, including those that affect both employment outcomes and the (unobserved) choice of school. The panel data model can be described as follows:

where the dependent variable Limrt is a labor market outcome of woman i living in municipality m and region r in year t. We analyze several employment outcomes, including participation in the labor force, employment, hours worked per week, months worked in the year, share of year worked, and two indicator variables for participating in the labor force and working than 50 percent of the previous 12 months. The policy variable of interest, FDSmrt, is the share of share of primary schools under FDS in municipality m and region r in year t, and measures the availability of full-day primary schools at the municipal level.

Equation (1) also includes individual and municipal characteristics in Ximrt and Mmt, respectively. Individual characteristics (Ximrt) include years of education, age, age squared, and an indicator for having a child of primary school age, which is defined as the child having 6–13 years of age. This latter variable is intended to capture the timing in which the policy should have an effect on mothers’ labor market outcomes. Municipal characteristics (Mmt) incorporate a set of variables that control for access to child care before primary school, as well as local labor market condition that could affect women´s labor market outcomes. These variables, discussed above, are: the share of schools with Pre-K and Kindergarten, average years of education in the adult population, municipal poverty rates, unemployment rates (female and male), and labor force participation rates (female and male). As we use longitudinal data, we are able to include an individual-level fixed effect αi, which allows us to control for individual unobserved heterogeneity in the labor participation and school decisions. Our estimation also includes municipal level time trends, μmt, and region-year fixed effects, τrt, to control for factors at the regional level that vary across time, such as regional labor market conditions, which may affect women’s labor outcomes or FDS access, among others.

Since we include individual fixed effects, our model estimates the effect of FDS schools from within-individual variation in FDS access, i.e., variation faced by the same mother through time. In our model, identification comes from two plausibly exogenous changes: (1) variation in the local supply of FDS primary schools at the municipal-level, and (2) changes in the age of children in the household, which determine mothers’ exposure to the policy. We measure both of these sources of variation by interacting the policy variable FDSmrt with an indicator variable Childimrt that equals one if the youngest child of mother i is of primary school age (6–13 years old) in year t, and zero otherwise. This means that we are comparing the labor market outcomes of mothers when their child is in primary school and can attend a full-day school, relative to the same mothers’ outcomes when her youngest child was in preschool (and could not attend full-day schools).

In Eq. (1), the effect of FDS availability is γ1 when the youngest child in a household is aged 5 or younger. If the policy is an implicit child care subsidy, FDS access should not affect mothers’ outcomes before their child is in primary school, i.e., γ1 = 0; we can test this directly in our results. The total effect of the policy on the same mother when her youngest child reaches primary school age is γ1 + γ2; we are interested in the impact of the policy once the mother can benefit from the policy (when her child is in primary school), so our discussion will focus on γ1 + γ2. With this estimation, the coefficients of interest (γ1 and γ2) can be interpreted as causal assuming that individuals’ preferences are stable through time. In the next section we explore possible threats to identification.

4.1 Threats to identification

There are three main threats to identification in our model; in this section we discuss how we have addressed them in our analysis. The first is the fact that families can choose schools in the public school system regardless of their residence, so that women that prefer to work may be more likely to enroll their child in a full-day school. This would be a problem if our policy variable was measured at the individual level. Due to data limitations, however, we construct a measure of potential access to FDS schools that families face in the municipality where they reside (FDSmrt). Given the decentralized nature of school-level decisions, FDS coverage at the municipal levels is plausibly exogenous to each family (whereas actual school choice is not), provided that FDS access at the municipal level is not correlated with families’ choice of residency. To assess this possibility, we estimated a model of municipality of residence choice following the approach in Borjas et al. (1992), where the decision to move to a different municipality depends on individual human capital and characteristics of the source and host municipalities. We found that municipal FDS coverage is not a relevant determinant for families’ location decisions, suggesting that families are not self-selecting into municipalities with higher access to FDS.Footnote 18

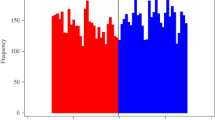

A second threat to identification is the possible correlation between the Government’s criteria for allocating FDS infrastructure funds and local female employment rates. Each year the Government prioritized infrastructure funds to schools that had high indices of socioeconomic vulnerability, therefore, it is possible that policy take-up was correlated with the likelihood that women work; this would violate the parallel trends assumption. We addressed this threat descriptively and analytically. Since all municipalities in our period of study had positive take-up rates, so that all municipalities had some level of “treatment,” we classified municipalities as “early” or “late” FDS adopters based on FDS take-up rates halfway through the implementation period: a municipality is a “late” adopter if take-up in 2004 was less than 1 standard deviation below the national average take-up rate. We then compared the trend in LFP, employment rates, and hour worked for females between these groups of municipalities. Figures 2, 3 and 4 reveal that all these outcomes followed almost identical pre-policy trends across both types of municipalities, which supports the parallel trends assumption.Footnote 19

Average of municipal female LFP rates (1990–2015), by early and late adoption of FDS program. Source: Authors’ estimates from CASEN surveys. Percent of women aged 25–55 that are economically active. Early or late adoption is defined based on whether FDS coverage in the municipality in 2004 was below the median implementation rate

Average of municipal female employment rates (1990–2015), by early and late adoption of FDS program. Source: Authors’ estimates from CASEN surveys. Percent of women aged 25–55 that are economically active. Early or late adoption is defined based on whether FDS coverage in the municipality in 2004 was below the median implementation rate

Average of municipal female hours worked (1990–2015), by early and late adoption of FDS program. Source: Authors’ estimates from CASEN surveys. Percent of women aged 25–55 that are economically active. Early or late adoption is defined based on whether FDS coverage in the municipality in 2004 was below the median implementation rate

Analytically, we control for preexisting trends in labor market outcomes by including categorical variable Dmr that classifies a municipality as “Low Labor Market Outcome” and then interact Dmr with year fixed effects. This clears the FDS effect of differences in female labor market outcomes trends across municipalities that may have existed prior to the first year of our study.Footnote 20 We also estimated a regression of the determinants of municipal-level FDS take up to assess whether it was driven by female labor force participation rates; we find that female employment and labor force participation rates do not have significant effects on municipal-level FDS implementation, nor do poverty rates in the municipality.Footnote 21

A final threat to identification would be if the childcare provided by longer school schedules affects mothers’ fertility decisions, thus affecting the age structure of children within the household. To assess this possibility, we estimated regressions to test whether access to primary schools with FDS affects mothers’ fertility, both contemporaneously (measured by whether the mother had child in the last 12 months), and overall (measured by the number of children aged 0–13 in the household). We find no effect of the FDS policy on either of those two measures of fertility.Footnote 22

5 Estimation results

Our baseline estimates of the effect of FDS access on mothers’ employment outcomes are reported in Table 3. We report the estimated coefficients of FDS coverage and its interaction term with the indicator variable for youngest child being in primary school, along with individual and municipal level control variables.Footnote 23 As discussed in the previous section, the effect of FDS access when the youngest child is of preschool age is represented by the coefficient of the FDS variable, while the effect when the youngest child reaches primary school and is potentially affected by the policy is represented by the sum of the coefficients of the FDS variable and the interaction with the variable for youngest child being in primary school. As we are interested in the sum of these two coefficients, at the bottom of each table we report the sum of coefficient γ1 and γ2, and the p-vale of an F-test of joint significance of FDS access and the interaction term.

Table 3 reveals that FDS access did not affect most employment outcomes of mothers when their youngest child was in preschool—the coefficient of the FDS variable is not statistically significant for most outcomes. This is reasonable because the policy did not apply to preschools. However, we find that when the youngest child reaches primary school and mothers potentially benefit from FDS access, all employment outcomes increase relative to when the child was in preschool.

The sum of γ1 and γ2—from Eq. (1)—represents the effect of an increase in the share of FDS schools in a municipality by 1 (or 100 percentage points). Column 1 of Table 3 reveals that such an increase would lead to an increase female LFP during the last 12 months by 22.6 percentage points (reported at the bottom part of the table), and which is obtained as the sum of γ1 (0.208) and γ2 (0.0176).

To put our results in a relevant context, in 2009, almost 70 percent of primary schools in our sample were FDS, so that increasing FDS coverage by 30 percentage points—equivalent to reaching full FDS coverage—would lead to a predicted increase in female LFP over a period of a year of 6.8 percentage points (0.226 times 0.3). Since approximately 75 percent of mothers participate in the labor market, the estimated marginal effect is equivalent to an increase in female LFP of 9.0 percent.Footnote 24 A similar increase in FDS coverage of 30 percentage points would lead to an increase in the likelihood of employment during a year of almost 8.1 percent, and to an increase of 3 h worked per week, or 10.8 percent (columns 2 and 3, respectively).

We also analyze if FDS access affects attachment to the labor market in a more permanent way, and find that greater access to full-day schools contributes to mothers’ attachment to the labor force for longer periods of time during the year, although with moderate effects. Although statistically significant, we find that increasing FDS coverage by 30 percentage points would lead to a small increase of 1 percent in months worked during the year (column 4), an increase of 2.8 percent in the share of the year worked (column 5), as well as increases of 5.3 and 2.3 percent in the likelihood of participating in the labor market and working for more than 6 months (columns 6 and 7).

Our results are larger than previous estimations of the effects of the FDS policy on mothers’ employment found in Contreras and Sepúlveda (2016), which we refer to as C&S below. The differences can be due to several factors, including: the estimation methodology, definition of outcomes, grade levels considered in the analysis, among others. Due to the longitudinal nature of our data, our methodology includes individual fixed-effects that capture time-invariant non-observables, including those correlated with preferences to participate in the labor market and child care arrangements; whereas the data in C&S is repeated cross-sections (CASEN household surveys), so that they cannot include individual fixed-effects. In a pooled cross-section setting, the estimated effects are biased if the policy is correlated with unobserved municipality characteristics that can affect mothers’ employment, or with unobserved individual preferences for employment, child care, and school choice. Indeed, C&S recognize that the FDS policy was rolled out in areas of higher poverty, and conclude that their estimated results are likely biased towards zero, underestimating the true effect of the policy.

Another difference with C&S is the definition of the labor market outcomes, since the period of reference for all employment questions in the EPS survey is the previous 12 months, whereas the employment questions in the C&S data are based on employment in the previous week. Thus, our data is more likely to capture effects of the policy because they can be detected not only during a short period (one week), but over the whole year. In terms of the age at which mothers benefit from the policy, we consider mothers with children between 6 and 13 years of age as having access to the FDS policy (i.e., from 1st through 8th grade), while C&S consider mothers with children aged between 8 to 13 years (i.e., 3rd through 8th grade). If the effects of the policy are more likely to affect women with younger children (those more in need of childcare), our results should also be larger than those reported by C&S.

5.1 Is FDS providing childcare?

Our baseline results suggest longer school schedules facilitate mothers’ entry and attachment to the labor force. As discussed above, the FDS policy could work through several mechanisms. Our results suggest that the policy is effective when families benefit from extended school schedules—i.e., when children reach primary school. By spending more hours in school, young children’s formal care is provided and the gap between school hours and parents’ work schedules is reduced. If child care is the more relevant mechanism, we would expect women’s participation and employment outcomes to be affected more directly during the school year and less so during the summer months. Since we have detailed data on women’s employment (each month), we analyzed whether the effects of FDS access were different during the months of the school year (March through December) than during the summer vacation months (January and February) when schools are closed and parents must find childcare arrangements. Table 4 presents these results. We observe that mothers participate more in the labor force during the school year (74.4 percent) than the summer months (67 percent), and their employment rates are also higher during the school year (63 vis-à-vis 54 percent). Regarding the effect of longer schedules, we find that an increase of 30 points in FDS school coverage leads to: (i) an increase in labor force participation by mothers throughout the school year of 8.2 percent (column 1) but only of 1.4 percent during the summer months (column 2); (ii) an increase in employment of 7.3 percent during the school year, and no effect during the summer months (columns 3 and 4, respectively); and (iii) an increase of 0.2 months worked, but only during the school year (column 5).

To further explore whether the FDS policy provides childcare for school-aged children, we estimated our regressions among three groups that are less likely to demand childcare: women without children in the household, women whose youngest child is in secondary school, and fathers. If school schedules affect women’s employment outcomes because they provide childcare for their children, then women that did not have children living in their household between 2002 and 2009 should not be affected by the FDS policy, and similarly, mothers with children in secondary school or above (i.e., 14 years old or older) should require less or no child care services. The effect of the policy on fathers is ambiguous ex-ante: fathers are less likely to be affected than mothers because in Chile, most households distribute household tasks along traditional gender roles, and men tend to be more attached to the labor force, especially in the presence of children—indeed, the bottom part of panel C in Table 5 reveals that fathers’ labor force participation and employment rates are 98 and 96 percent, respectively. However, it is possible that fathers are positively affected by the FDS policy if their labor supply is also constrained by the supply of childcare, or affected negatively if the FDS-induced entry of mothers into the labor force leads to intra-household substitution of hours dedicated to the labor market.

We present our results in Panels A, B and C of Table 5, respectively. We find that when no children are present in the household or when the youngest child is in secondary school, the policy has no effect on women’s employment. This results should be expected, as women without children do not require childcare services and receive no benefits from the FDS policy, so that their labor market decisions should not be affected by the roll-out of the policy. Similar results for women whom their youngest child is of secondary school age, indicating that the policy does not affect their labor market decisions.

We also find that the policy does not affect most employment outcomes of fathers. An increase of 30 percentage points in FDS coverage increases months worked by 1.0 percent, increases the share of the year worked by 2.8 percent, and increases the likelihood of being in the labor force for more than half of the year by 5.3 percent. These effects are positive and similar in magnitude relative to the effect on mothers. Overall, our results provide evidence that extended schedules provide childcare services that help mothers enter de labor market, and they increase the attachment to labor market of mothers and fathers.

5.2 Heterogeneous effects of the FDS policy

We are also interested in analyzing whether the policy had heterogeneous effects. In particular, we look at differential effect for women of different socio–economic levels and by their head of household status. In order to analyze socio–economic levels, we proxy socioeconomic status with mothers’ education (in the first year she was surveyed), because income is endogenous to her employment decisions. Since longer schedules are essentially subsidized care for children by schools, we expect the effect to differ by socio–economic levels because lower-income mothers are more budget-constrained relative to high-income women who are able to pay for alternative childcare services. We defined a mother as having a low level of education if her level of school completion was 12 years of schooling or less (equivalent to high school or less), and she has a high level of education if her school completion was 13 years or more. Also, the literature has found that childcare policies may have differential effects for women that are single or heads of their households vis-à-vis women who are not. So we estimate our model by head of the household status of the mother. Results from regressions for both exercises are reported in Table 6.

We find that the FDS policy has greater effects on employment outcomes of lower-education women (Panel A of Table 6). Among this group, increasing FDS coverage by 30 percentage points leads to increases in the predicted probability of labor force participation and employment of 11.8 and 9.8 percent, respectively; in weekly hours and months worked of 13.8 and 0.6 percent, respectively, and in the probability of participating in the labor force and of working during most of the year by 7.2 and 1.4 percent, respectively. Among higher-education women, the same increase in access to FDS schools only increases labor force participation by 0.5 percent (Panel B, column 1), and the probability of participating in the labor force by 0.2 percent (Panel B, column 6).

For women who are not the head of their household, we find that the policy positively affects all labor market outcomes: an increase of FDS coverage by 30 percentage points increases LFP 10.3 percent, employment by 8.9 percent, hours worked per week by 11.4 percent, months worked during the year by 3.9 percent, the share of the year worked by 5.1 percent, and the likelihoods of participating in the labor market and of working for more than 6 months by 7,0 and 8.1 percent, respectively. In contrast, the policy has no significant effect on any the labor market outcomes of women who are head of household. We find similar results when considering women with and without spouse or partner, finding that all effects are concentrated among women with a spouse or partner. It is likely that women who are head of their household or single have a stronger attachment to the labor market than spouses or married women, so that they have arranged for child care prior to the policy and they are less sensitive to the policy implementation. The literature finds that the impact of childcare across head of household or civil status is highly context-dependent (Cascio et al., 2015); our results are consistent with Berlinski and Galiani (2007), Baker et al. (2008), and Boll and Lagemann (2019), which find positive effects of childcare access on married mothers in Argentina, Canada and Germany, respectively.

5.3 Robustness checks

We report a series of robustness checks in Table 7, which we carried out to ensure that our estimates are not driven by our sample design, variable definition, or spillover effects from other policies. First, as discussed in Section 2, families are not constrained to schools in their same municipality of residence, so that our definition of access—share of FDS schools in the municipality of residence—may be imprecise if many families reside in a municipality different from where the school is located. To address this potential measurement error, we excluded from our regressions the three metropolitan areas of Chile where, due to geographic proximity, families are more likely to enroll children in a different municipality. The three metro areas are: Metropolitan Region (Santiago, the capital), Concepcion, and Valparaiso (the second and third largest metropolitan areas, respectively). Estimates reported in Panel A of Table 7 reveal that results are very similar to those in Table 3 in terms of direction and magnitude of the effects of the policy (we expect statistical significance to dwindle because the sample size is reduced almost in half).

Second, in 2006, Chile began to expand public daycare and early preschool centers available for children aged between 3 months and 4 years of age. It’s possible that part of the increase in mothers’ employment that we observe is capturing spurious correlation between the Daycare Policy and the FDS reform. The policies were not coordinated and were implemented independently, and they were overseen by separate public institutions; nonetheless, to rule out the possibility that our estimated results are partially capturing the expansion in daycare center coverage, we estimated regressions that exclude mothers who could have potentially benefitted from the daycare expansion policy, i.e., we exclude mothers with children aged 3 months to 4 years old in 2006 and 2009, which are the years in our sample in which mothers could have benefitted from the daycare expansion policy, If our results are not capturing the effects of the Daycare Policy, then the estimates with and without these women should be similar. We present these results in Panel B of Table 7; comparison to the baseline estimates in Table 3 reveals that the effects of the FDS policy are similar in magnitude (we expect some reduction in statistical significance because the sample size is smaller), which suggests that our main results are not driven by the national Daycare Policy during part of the period of analysis.

Finally, as our main estimates exclude women that changed municipality of residence during the period, one concern could be that our sample contains a self-selected sample of women. In Panel C of Table 7 we add mothers that moved to a different municipality to the sample of mothers in our baseline regressions. Again, the results are similar to our baseline estimates.

6 Conclusions

Mothers of school-aged children in Chile cite lack of adequate child care as the second most important reason for not participating in the labor market. This suggests that making school schedules compatible with work schedules could facilitate women’s employment, and consequently increase household incomes and family well-being. The literature has mostly analyzed expansions of publicly provided preschool in developed countries; we know relatively less about the role of school schedules in employment decisions of mothers of primary school-aged children. In this paper we analyzed a nation-wide school reform in Chile that lengthened the school day in primary schools from half to full day schedules, and its impact on mothers’ labor force participation, employment, and attachment to the labor force.

We identified the causal effect of the policy from its quasi-experimental implementation and the exogenous variation in children’s ages using a panel that allows us to control for individuals’ unobserved heterogeneity, such as preferences regarding fertility, work, or childcare arrangements for children. We find that increased availability of full day (FDS) primary schools in the municipality significantly increases the likelihood that mothers participate in the labor force and work, and they are more likely to remain attached to the labor force for longer periods throughout the year. If the supply of primary schools were to reach full coverage—i.e., increase by 30 percentage points—, mothers’ LFP and employment during a period of a year would increase by approximately 9 percent, they would work on average 3 h per week and an additional 0.2 months during the year. These findings suggest that lack of access to childcare for primary school aged children in Chile could explain—at least partly—the country’s low female participation rates, which is consistent with recent findings for other developing countries (Chioda et al., 2011; Martinez & Perticara, 2017).

Our findings complement and extend those reported by Contreras and Sepúlveda (2016) and Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hernández 2019, which analyze the effect of full-day school reforms in Chile and Mexico, respectively. We arrive at similar conclusions regarding extensive-margin measures of employment; however, the magnitude of the effects estimated with our data are larger than the previous two studies, which predict that a 30-point increase of FDS access would increase mothers’ LFP by 1.5 and 3.7 percent, respectively. These differences are due to slightly different control groups and periods of analysis. Our results—which are larger in magnitude—are identified from the discrete change in school levels by the youngest child in the household, i.e., the transition between preschool and primary school. In contrast, both of the papers cited above analyzed the effect of FDS access while children were already enrolled in primary school, so that the parameters estimated reflect more gradual changes, and Padilla-Romo and Cabrera-Hernández 2019 estimate cumulative, individual effects over 15-month periods.

In this paper we also analyze attachment to the labor force, and discover that in addition to participation and employment decisions, women worked more hours, more months during the year, and had a more permanent attachment to the labor force as a result of the FDS policy. The positive effects of access to FDS schools are concentrated in the months that schools are in session (March–December in Chile), suggesting that lack of child care in the summer months may be constraining mothers’ ability to participate in the labor market.

Finally, we find that lower-education women benefit most from the FDS policy in terms of their employment decisions and attachment to the labor market during the year, relative to high-education women. The implicit subsidy of extended school schedules, which reduce the need to arrange formal after-school care for primary school children, alleviates at least part of families’ financial constraints, and permits mothers to enter and remain in the work force for longer periods of time. This suggests that by facilitating mothers’ entry and attachment to the labor force, particularly women who are socio–economically vulnerable, the FDS policy can help reduce poverty and income-inequality.

These results have important policy implications for other countries that are considering similar policies of school schedule extensions, such as Germany, Colombia, Argentina, Uruguay, and Peru. If policy makers wish to support women’s entry and attachment to the labor market, then authorities should consider policies that make women’s employment and their children’s school schedules more compatible. Overwhelmingly, school hours fall short of most countries’ weekly work schedules. Our work shows that extending them and closing the gap has important benefits for mothers wishing to work.

Notes

An earlier study that analyzed the impact of the Chilean FDS policy (using repeated cross sections of household surveys) found that greater access to FDS schools had positive effects on female labor force participation and employment, yet negative effects on hours worked (Contreras & Sepúlveda, 2016).

The reform is referred to as JEC in Chile, due to the Spanish acronym of its official name, Jornada Escolar Completa, approved in law Nr.19,532.

According to CASEN (2009), almost 50% of mothers with youngest child in preschool and 25% of mothers with youngest child in primary school declared lack of child care as the main reason for not participating in the labor force, compared to 4% of mothers with youngest child in secondary-school.

During the period of study, two types of publicly funded schools existed in Chile: municipal schools—which are owned by municipal governments and publicly funded—and voucher schools, which are privately owned and co-funded by parents (through fees and tuition) and public funds (from the central and municipal governments). Fully private schools, which represent 8% of enrollment, are privately owned and do not receive public funding; they were not obligated to ascribe to the FDS program, so we do not include them in our analysis.

Schools were allowed to switch into the FDS regime gradually, offering full-day schedules for some of its grade levels as long as all classes within a grade level were FDS.

The most important expense (and constraint) associated with a full-day school is the expansion of schools’ infrastructure to accommodate, in many cases, twice the number of students at any given time. Financially constrained schools that wished to adopt the reform competed for public funds through an application process with the Ministry of Education, which followed administrative criteria to select among the applying schools. However, there is no publicly available information that reports how the actual funds-allocation process was carried out, nor which criteria were followed. To cover operational costs, the per-student subsidy paid to all public and voucher schools increased by 40%.

We did not include the 2012 and 2015 rounds; the 2012 has been deemed as “incomplete” and the Ministry of Labor (the agency that implemented the survey) does not recommend its use (see Ministerio del Trabajo y Previsión Social, https://www.previsionsocial.gob.cl/sps/biblioteca/encuesta-de-proteccion-social/bases-de-datos-eps). We do not have information on the municipality of residence for 2015, which is needed in order to match the availability of FDS schools in the municipality of residence with mothers’ labor outcomes.

Publicly available EPS data does not include individuals’ municipality of residence, which is required to merge EPS individuals’ data with the policy variable and other municipal characteristics. We obtained access to individuals’ municipality of residence for the 2002 through 2009 rounds by requesting it to the curators of the survey, which can be requested at https://www.previsionsocial.gob.cl/sps/biblioteca/encuesta-de-proteccion-social/bases-de-datos-eps/. We are willing to guide researchers through the request process upon request.

As a robustness check, we also constructed FDS access as the fraction of primary school enrollment that is under full-day schedules in the municipality. We prefer the first measure of FDS access—share of schools—because it is a better reflection of the information parents consider in the school decision. In the main part of the paper, we report results using this measure. Baseline results using the FDS measure based on enrollment are similar to those reported in the paper, and can be found in Appendix 1. All other estimates using the enrollment measure are available upon request.

We only include women’s age, years of education, and the indicator variable for a child of primary school age as individual controls to avoid possible endogeneity between other individual characteristics and the FDS policy during the period. However, we also estimated models with other control variables and our results are robust to their inclusion. These additional control variables include the woman being head of the household, having a spouse/partner, and several variables capturing household composition demographics.

In our data, 10.8 percent of mothers migrated to a different municipality between 2002/2004 and between 2004/2006, and 7.5 percent of mothers migrated between 2006 and 2009. Our results are similar with and without women that migrated; baseline results including women who migrated are reported in Table 7, Panel C.

The sum of the number of women in columns 2 and 3 does not have to add to the total number of women as the same women may be part of each subgroup in different periods.

The attrition rate between 2002 and 2009 is approximately 15 percent. Appendix 2 presents a complete analysis of attrition, describing attrition rates, differences in observable characteristics between mothers that persist in the panel and those that do not, as well as an analysis of the determinants of attrition. We find that FDS access and most observable characteristics are not correlated with attrition.

This measure of labor force status in the EPS has a longer reference period (12 months) than other surveys in Chile (with reference periods for labor force participation of one week or one month); consequently, the rates of labor force participation and other labor market outcomes in the EPS data are higher than other Chilean surveys. However, individual characteristics in the EPS data are comparable to other surveys.

Measured with enrollment, the average rate of FDS access is 47 percent.

In the percentage of women with their youngest child of primary school age is 56.6 percent in 2002, 62.8 percent 2004, 68.9 percent in 2006, and 74.3 percent in 2009.

Appendix 3 reports estimates of a linear probability model of the likelihood of mother´s migration. Our estimates show that migration decisions are not affected by FDS access.

The large dips in LFP, employment and hours works around 1997-2000 and 2008-2009 are explained by the Asian financial crisis and the subprime crises, respectively (both of them generated recessions in Chile in 1999 and 2009).

Due to data availability, we can construct Dmr indicators using data from the 2000 CASEN for LFP, employment and hours worked outcomes. For all other outcomes—months worked, share of year worked, and LFP and employment in 7 or more months—it is not possible to construct corresponding variables of initial conditions from CASEN surveys; thus, we use the Dmr indicator that is most related to the dependent variable.

See Appendix 4 for a complete description and discussion of these results.

Appendix 5 presents our estimates. A related literature has analyzed the effect of access to longer schedules of secondary schools on fertility outcomes of women when they are of secondary school age, finding that longer schedules of secondary schools reduces teenage pregnancy (Berthelon & Kruger, 2011) and delays age of first births (Dominguez & Ruffini, 2021). In this literature, longer school schedules affect fertility through different channels: the incarceration (or monitoring) effect of being under adult supervision during longer periods during the day, and through the human capital effect of accumulating more hours of education. In contrast, in our setting, we analyze the effect of increased access to FDS primary schools, which does not affect adult women/mothers directly (i.e., through incarceration or human capital effects) but indirectly through another channel, which is the provision of childcare for their children. Therefore, given that the policy can act through these different channels, the effects of FDS on mothers’ fertility outcomes should not be comparable.

For ease of exposition we do not report municipal level time trends, region-year fixed effects and trends for pre-reform labor market outcomes. Complete estimates are available upon request.

Marginal effects are calculated by dividing the estimated coefficient by the mean of the dependent variable, and multiplying by 0.3. For instance, the marginal effect of an increase in FDS coverage of 30 percentage points on labor force participation is obtained by dividing the sum of the estimated coefficients γ1 + γ2 which is equal to 0.2256 by the mean of the dependent variable, 0.748 (shown in the bottom of Table 3) and multiplying the result by 0.3.

Municipal characteristics are constructed from CASEN Household Surveys carried out in 1996, 1998, 2000, 2003 and 2006.

We also estimated the model with contemporaneous municipal characteristics; the results were unchanged.

SIMCE (Sistema de Medición de la Calidad de la Educación) tests are a series of standardized test administered to 4th, 8th and 10th grades in all schools in Chile. For the period of study, we have data on language and math test in 4th grade for 2000, 2003, 2006 and 2009. In 1998 we only have data on 10th grade scores, which we still use to measure quality in primary schools for 1997 and 1999. Results are not sensitive to different test score measures or to the exclusion of this variable.

References

Baker, M., Gruber, J., & Milligan, K. (2008). Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. Journal of Political Economy, 116(4), 709–45.

Barua, R. (2014). Intertemporal substitution in maternal labor supply: Evidence using state school entrance age laws. Labour Economics, 31, 129–40.

Bellei, C. (2009). Does lengthening the school day increase students’ academic achievement? Results from a natural experiment in Chile. Economics of Education Review, 28(5), 629–40.

Berlinski, S., Galiani, S., & Mc Ewan, P. (2011). Preschool and maternal labor market outcomes: evidence from a regression discontinuity. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 59(2), 313–44.

Berlinski, S., & Galiani, S. (2007). The effect of a large expansion of pre-primary school facilities on preschool attendance and maternal employment. Labour Economics, 14(3), 665–80.

Berthelon, M., & Kruger, D. (2011). Risky behavior among youth: Incapacitation effects of school on adolescent motherhood and crime in Chile. Journal of Public Economics, 95(1), 41–53.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2013). Female Labor Supply: Why Is the United States Falling Behind? The. American Economic Review, 103(3), 251–56.

Boll, C., & Lagemann, A. (2019). Public childcare and maternal employment—New evidence for Germany. Labour, 33(2), 212–39.

Borjas, G. J., Bronars, S. G., & Trejo, S. J. (1992). Self-selection and internal migration in the United States. Journal of Urban Economics, 32(2), 159–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9227-4.

Brilli, Y., Del Boca, D., & Pronzato, C. D. (2016). Does child care availability play a role in maternal employment and children’s development? Evidence from Italy. Review of Economics of the Household, 14(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9227-4.

Cannon, J. S., Jacknowitz, A., & Painter, G. (2006). Is full better than half? Examining the longitudinal effects of full-day kindergarten attendance. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 25(2), 299–321.

Cascio, E. U. (2009). Maternal labor supply and the introduction of kindergartens into American public schools. The Journal of Human Resources, 44(1), 140–70.

Cascio, E. U., Haider, S. J., & Nielsen, H. S. (2015). The effectiveness of policies that promote labor force participation of women with children: A collection of national studies. Labour Economics, 36, 64–71.

Chioda, L., Garcia-Verdu, R., & Muñoz, A. M. (2011). Work and Family: Latin American and Caribbean Women in Search of a New Balance. Washington, D.C: World Bank.

Contreras, D., & Sepúlveda, P. (2016). Effect of Lengthening the School Day on Mother’s Labor Supply. World Bank Economic Review, 31(3), 747–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhw003.

Del Boca, D. (2002). The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. Journal of Population Economics, 15(3), 549–73.

Dominguez, P., Ruffini, K. (2021) Long-Term Gains from Longer School Days. Journal of Human Resources, https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.59.2.0419-10160R2.

Finseraas, H., Hardoy, I., & Schøne, P. (2017). School enrolment and mothers’ labor supply: evidence from a regression discontinuity approach. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(2), 621–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9350-0.

Fitzpatrick, M. D. (2012). Revising our thinking about the relationship between maternal labor supply and preschool. The Journal of Human Resources, 47(3), 583–612. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.47.3.583.

Felfe, C., Lechner, M., & Thiemann, P. (2016). After-school care and parents’ labor supply. Labour Economics, 42, 64–75.

Gelbach, J. (2002). Public schooling for young children and maternal labor supply. American Economic Review, 92(1), 307–22.

Graves, J. (2013). School calendars, child care availability and maternal employment. Journal of Urban Economics, 78, 57–70.

Lefebvre, P., & Merrigan, P. (2008). Child-care policy and the labor supply of mothers with young children: A natural experiment from Canada. Journal of Labor Economics, 26(3), 519–48.

Martínez, C., & Perticara, M. (2017). Childcare Effects on Maternal Employment: Evidence from Chile. Journal of Development Economics, 126, 127–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.01.001.

Padilla-Romo, M., & Cabrera-Hernández, F. (2019). Easing the constraints of motherhood: the effects of all-day schools on mothers’ labor supply. Economic Inquiry, 57, 890–909. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12740.

Sall, S. P. (2014). Maternal labor supply and the availability of public pre-K: Evidence from the introduction of prekindergarten into American public schools. Economic Inquiry, 52, 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12002.

Takaku, R. (2019). The wall for mothers with first graders: availability of afterschool childcare and continuity of maternal labor supply in Japan. Review of Economics of the Household, 17(1), 177–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-017-9394-9.

United Nations Women (2020). The Impact of Marriage and Children on Labour Market Participation: Spotlight on Goal 8. Spotlight on the SDGs Working Paper Series. United Nations. https://doi.org/10.18356/88f157a4-en.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank seminar participants at the University of Chile, Catholic University of Chile, Oregon State University, University of Maryland, the Northwest Development Workshop, the Inter American Development Bank, and Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez. We also thank an anonymous referee for comments and suggestions. Berthelon and Kruger received financial support from Chile’s National Committee of Scientific and Technological Research (Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, CONICYT), through FONDECYT Project No. 1120882. Berthelon and Kruger would like to thank funding provided by the Center for Studies of Conflict and Social Cohesion (ANID/FONDAP/15130009). The authors thank the Sub-Secretariat of Social Provision for granting permission for the use of Chile’s Social Protection Surveys. All results, errors and omissions are sole responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Baseline estimates using the FDS measure of enrollment

Table 8

Appendix 2: attrition in EPS survey

Our sample includes women who are mothers of children of preschool or primary-school age during the survey year, and whose child attends primary school in at least one of the panel years. Attrition rates for our sample between 2002 and 2009 are below 15% (see Table 9) It is relevant that since our sample is composed of mothers with children of preschool or primary-school age, as children get older, mothers exit the panel. We performed two analyses to explore whether attrition is a serious problem in our data. Our first analysis is descriptive: we compared mothers’ observable characteristics in 2002 (the initial year) were significantly different for those who remained in the panel through 2009 and those that did not. The results are reported in Table 10.

We find that in 2002, among all women in the EPS surveys, women who did not appear in the 2009 round had slightly less access to FDS schools in 2002 than women who were followed up in 2009. Furthermore, relative to women who remain in the panel, they were: 5 years older, more likely to be head of the household, and less likely to have a partner; their household size was smaller; they had 0.5 fewer years of education, were less likely to have worked, yet had higher incomes. Their municipalities of residence had higher average education and income, and lower poverty rates.

We found fewer differences in observable characteristics among women in our sample—mothers of a child aged 13 or less and was in primary school during the panel years: mothers who were not followed in 2009 were 1.2 years older and had higher income in 2002. Although the differences in the means of these observable variables were statistically significant between these groups, most of the differences were not economically large.

Since observable characteristics may be correlated, in our second analysis, for mothers who were surveyed in 2002, we estimated regressions of the determinants of the probability of remaining in the panel in 2004, 2006 and 2009. Our control variables include FDS access, as well as individual and municipal characteristics; we present these results in Table 11. We find that individual (and municipal) characteristics do not affect the likelihood of persistence in the panel, including access to FDS. The age of the youngest child does affect attrition: mothers of older children in 2002 were less likely to remain in the panel through 2009, revealing that attrition is mostly due to our sample selection criteria.

Appendix 3: migration

Table 12

Appendix 4: determinants of municipal full-day schooling implementation

In this section we analyze whether FDS implementation is exogenous to women’s labor market outcomes by estimating a model of the determinants of municipal full-day schooling implementation. We regress our policy variable of interest—share of FDS at the municipal level—on several municipal characteristics.Footnote 25 Our model can be represented as:

where the dependent variable FDSmrt is the share of full-day primary schools in municipality m and region r in year t. Mmrt−1 is a vector of pre-determined municipality-level characteristics. We estimate this model using the previous year’s municipal characteristics because the decision to enter FDS by schools in period t, had to be taken at least in period t−1, so that if local conditions affect the decision to adopt the policy, they should be measured prior to entry into FDS.Footnote 26 Municipal-level variables include: total enrollment in primary schools (in thousands of students), number of students per school (in thousands), average years of schooling in the municipality (for population aged 15 years or older), municipal poverty rate, average (autonomous) household income per capita (in logs), fraction of the population that lives in rural areas, male and female employment rates, male and female labor force participation rates (for the population aged 15 years or older), and average school quality (measured by average scores from the national standardized math and language test, SIMCE).Footnote 27 Depending on the estimated model, we include region-year fixed effects (ωr) and/or municipal fixed effects (φm).

We report results from these regressions in Table 9. First, we estimate equation (A1) for each year in which we have both FDS data and data on municipal characteristics. These series of cross section estimates allow us to see whether differences in several municipality characteristics can explain differences in FDS take-up rates in different years. Column 1 reports estimates for the first year of the policy’s implementation, 1997. The estimates indicate that initial full-day schooling implementation was greater in municipalities with smaller schools. Neither socio–economic variables (such as years of education, poverty rates, income and rural population) nor labor market outcomes for men or women are significant determinants; thus, we can rule out that the policy responds to mothers’ labor outcomes. At the same time, the role of school quality is ambiguous, for municipalities with higher average test scores in language had larger initial takes-up rates, but the opposite happened in terms of math scores.

Next, when we analyze the level of implementation of the policy in the following years (columns 2–5), we find that in the earlier years of the reform (in 1999), higher take-up rates are observed in municipalities with smaller schools, but no effect is observed for school quality. We also find that the policy had higher take-up rates in municipalities with larger shares of rural population. In subsequent years (2001, 2004 and 2007), we find that the policy implementation was larger in smaller municipalities (measured by total enrollment in primary schools), in more rural municipalities and with lager rates of labor force participation among men.

We pooled all years of our data and estimated our model with and without municipal fixed-effects (columns 5 and 6). We find similar results with the cross sectional municipality variation: smaller and more rural municipalities, with large LFP in the male population, had higher take-up rates, and women’s labor market outcomes were not associated with the policy (column 6). When estimations are performed including municipal fixed effects, we find that within municipality changes in average school size and years of education were associated with larger levels of FDS. As average school sizes and average years of education (in the population older the 15 years) increased, the take-up rates increased within municipalities.

Table 13

Appendix 5: fertility and full-day schooling

Table 14

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berthelon, M., Kruger, D. & Oyarzún, M. School schedules and mothers’ employment: evidence from an education reform. Rev Econ Household 21, 131–171 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09599-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09599-6

Keywords

- Full day schooling

- School schedules

- Female employment and labor force participation

- Education reform

- Latin America

- Chile