Abstract

Tax benefits targeted to low-wage workers have become very common transfer programs that seek to meet both efficiency and equity targets. An expanding literature has assessed the effects of these policies on income distribution and labor supply showing important implications for female labor participation. In this paper, we estimate the distributional and behavioral impacts of a simulated new benefit in Spain based on the replacement of the existing working mother tax credit (WMTC) using as a reference the US Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). We simulate the effects of the proposed scheme using EUROMOD and a discrete choice model of labor supply. Our results show that the enhancement of the proposed reform would have significant and positive effects both in terms of female labor participation and inequality and poverty reduction. The introduction of this benefit would generate a substantial increase in labor participation at the extensive margin and a non-negligible reduction at the intensive margin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In terms of allowing them to change their labor supply, although not all of them will be affected by the reform.

Most women working full-time pay enough contributions to receive the benefit.

A similar result was found by Brewer (2001) for the US. The reason why this happens is because people might interpret this payment as an extra salary for holidays or special expenditures.

Saez (2002) suggests that, when behavioral responses are concentrated along the intensive margin, the best scheme is a traditional means-tested benefit with a substantial guaranteed income support and a large phase-out tax rate. By contrast, when behavioral responses are concentrated on the extensive margin, the optimal scheme is a transfer program with negative marginal tax rates at low income levels and a small guaranteed income.

The impact of the WTC is affected by the Child Tax Credit (CTC), making the combination of the two a more complex proposal to be simulated as compared to the EITC.

Family-based tax benefits are more common in Anglo-Saxon countries, whereas Belgium—the so-called “Employment Bonus”, a rebate on low skilled social security contributions—and France—“La Prime Pour l’Emploi”, a tax credit for low-income households—have implemented individual tax benefits. Family income-based eligibility rules and their interactions with other features of the tax-benefit system make the analysis of their impact on work incentives quite complex. In general terms, individual tax benefits ultimately promote work incentives, whereas family-based tax benefits tend to discourage the labor participation of second earners.

Considering children’s ages is important in the design of tax benefits, as households with younger children usually show stronger behavioral responses. Blundell and Shephard (2012) studied the optimal design of these policies for low-income families and highlighted the importance of including age in the design of the incentives.

Given their different labor behaviors, only women aged 18–60 except self-employed and disability pensioners are included within the scheme. They are not included because their different labor behavior.

In social policy debates in Spain, “mileurista” is a popular neologism that refers to a person who earns 1000 euros a month.

With the economic crisis, an important part of the lower wages fell to levels close to that minimum.

Men’s reactions have not been considered, as the proposed new policy does not apply to them. Regardless, we follow the conclusions of Bargain and Peichl (2013), who reviewed 282 estimated elasticities for OECD countries and found that elasticities are much higher for women than for men, which are positive but very small in most cases.

The classification of the regions is as follows: Region 1 = Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria; Region 2 = Basque Country, Navarre, Rioja, Aragón; Region 3 = Madrid; Region 4 = Castille and León, Castille-La Mancha, Extremadura; Region 5 = Catalonia, Valencia, Balearic Islands; Region 6 = Andalusia, Murcia, Ceuta, Melilla; Region 7 = Canary Islands.

According to our results, 66% of the marginal utilities are positive. Some authors, like Liégeois and Islam (2013), incorporate ex-ante on the likelihood function the constraint that all individuals have positive marginal utilities. Imposing such a restriction would, however, modify the behavior of the data.

Since we define three possible states in terms of the number of hours worked (0, 20 and 40 h), the estimates focus on the changes that the new tax benefit would produce in the probability of moving from one of those states to another.

Different models were estimated for single women and women cohabiting with their spouses but the estimated model in the case of the former did not converge.

Fixed costs were introduced as a disposable income reduction when women decide to work 20 or 40 h.

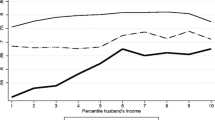

Most women reducing the number of hours worked are in the higher income deciles whereas the ones in the lower deciles are encouraged to entering into the labor market.

We calculate a weighted mean using the transition probabilities and the expected disposable income in the three hypothetical states (working 0, 20 or 40 h).

We use fixed poverty lines.

The poverty rate of single-parent households would decrease from 41.5 to 24.1%, and that of couples with children would decrease from 24.0 to 17.5%.

References

Aaberge, R., Colombino, U., & Wennemo, T. (2009). Evaluating alternative representations of the choice sets in models of labour supply. Journal of Economic Surveys, 23, 586–612.

Aaberge, R., Dagsvik, J. K., Strøm, S., & Strom, S. (1995). Labour supply responses and welfare effects of tax reforms. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 97, 635–659.

Adiego, M., Cantó, O., Levy, H., & Paniagua, M. (2012). EUROMOD country report. Essex: Institute for Social and Economic Research.

Azmat, G., & González, L. (2010). Targeting fertility and female participation through the income tax. Labour Economics, 17, 487–502.

Badenes, N. (2001). IRPF, eficiencia y equidad: tres ejercicios de microsimulación. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Fiscales.

Bargain, O., & Orsini, K. (2006). In-work policies in Europe: killing two birds with one stone? Labour Economics, 13, 667–697.

Bargain, O., & Peichl, A. (2013). Steady-state labour supply elasticities: a survey ZEW Discussion Paper No. 13-084.

Baughman, R., & Dickert-Conlin, S. (2009). The earned income tax credit and fertility. Journal of Population Economics, 22, 537–563.

Blundell, R. (2006). Earned income tax credits policies: impact and optimality: the Adam Smith Lecture 2005. Labour Economics, 13, 423–443.

Blundell, R., Bozio, A., & Laroque, G. (2013). Extensive and intensive margins of labour supply: working hours in the US, UK and France. Fiscal Studies, 34, 1–29.

Blundell, R., Costa Dias, M., Meghir, C., & Shaw, J. (2016). Female labor supply, human capital, and welfare reform. Econometrica, 84, 1705–1753.

Blundell, R., & MaCurdy, T. (1999). Labour supply: a review of alternative approaches. In O. Ashenfelter, D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labour economics, Vol. 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Blundell, R., & Shephard, A. (2012). Employment, hours of work and the optimal taxation of low-income families. The Review of Economic Studies, 79, 481–510.

Bonhomme, S., & Hospido, L. (2017). The cycle of earnings inequality: evidence from spanish social security data. The Economic Journal, 127, 1244–1278.

Brewer, M. (2001). Comparing in-work benefits and the reward to work for families with children in the US and the UK. Fiscal Studies, 22, 41–77.

Brewer, M., Francesconi, M., Gregg, P., & Grogger, J. (2009). In-work benefit reform in a cross-national perspective—introduction. The Economic Journal, 119, 1–14.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., & Saez, E. (2013). Using differences in knowledge across neighborhoods to uncover the impacts of the EITC on earnings. American Economic Review, 103, 2683–2721.

Chetty, R., & Saez, E. (2013). Teaching the tax code: earnings responses to an experiment with EITC recipients. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5, 1–31.

Creedy, J. (2005). An in-work payment with an hours threshold: labour supply and social welfare. The Economic Recod, 81, 367–377.

Crossley, T. F., & Jeon, S. (2007). Joint taxation and the labour supply of married women: evidence from the Canadian tax reform of 1988. Fiscal Studies, 28, 343–365.

Creedy, J., & Kalb, G. (2005). Discrete hours labour supply modelling: specification, estimation and simulation. Journal of Economic Surveys, 19, 697–738.

De Luca, G., Rossetti, C., & Vuri, D. (2014). In-work benefits for married couples: an ex ante evaluation of EITC and WTC policies in Italy. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 3, 23.

Díaz, M. (2004). La Respuesta de los contribuyentes ante las reformas del IRPF, 1987–1994. Tesina CEMFI 0405.

Eissa, N., & Hoynes, H. W. (2004). Taxes and the labor market participation of married couples: the earned income tax credit. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1931–1958.

Eissa, N., Kleven, H. J., & Kreiner, C. T. (2008). Evaluation of four tax reforms in the United States: labour supply and welfare effects for single mothers. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 795–816.

Eissa, N., & Liebman, J. B. (1996). Labour supply response to the earned income tax credit. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111, 606–637.

Figari, F. (2010). Can in-work benefits improve social inclusion in the Southern European countries? EUROMOD Working Paper No. EM4/09.

Fisher, P. (2016). British tax credit simplification, the intra-household distribution of income and family consumption. Oxford Economic Papers, 68, 444–464.

Francesconi, M., & van der Klaauw, W. (2007). The socioeconomic consequences of “in-work” benefit reform for British lone mothers. The Journal of Human Resources, 42, 1–31.

Fuenmayor, A., Granell, R., & Higón, F. (2006). La deducción para madres trabajadoras: un análisis mediante microsimulación. Boletín Económico de ICE N° 2874.

Fuenmayor, A., Granell, R., & Mediavilla, M. (2017). The effects of separate taxation on labor participation of married couples. An empirical analysis using propensity score. Review of Economics of the Household (forthcoming).

Grogger, J., & Karoly, L. (2009). The effects of work-conditioned transfers on marriage and child well-being: a review. Economic Journal, 119, 15–37.

Guyton, J., Manoli, D.S., Schafer, B., & Sebastiani, M. (2016). Reminders & recidivism: evidence from tax filing & EITC participation among low-income nonfilers. NBER Working Paper No. 21904.

Hotz, V., & Scholz, K. (2003). The earned income tax credit. In R. Moffitt (Ed.), Means-tested transfer programs in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hoynes, H., Miller, D., & Simon, D. (2015). Income, the earned income tax credit, and infant health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7, 172–211.

Hoynes, H.W., & Patel, A.J. (2015). Effective policy for reducing inequality? The earned income tax credit and the distribution of income. NBER Working Papers 21340.

Hoynes, H., & Rothstein, J. (2017). Tax policy toward low-income families. In A.J. Auerbach and K. Smetters (Eds.), The economics of tax policy. Oxford: University Press.

Immervoll, H., & Pearson, M. (2009). A good time for making work pay? Taking stock of in-work benefits and related measures aross the OECD. OECD Social, employment and migration Working Papers 81.

Labeaga, J. M., Oliver, X., & Spadaro, A. (2008). Discrete choice models of labour supply, behavioural microsimulation and the Spanish tax reforms. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 6, 247–273.

Lalumia, S. (2008). The effects of joint taxation of married couples on labor supply and non-wage income. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 1698–1719.

Liégeois, P., & Islam, N. (2013). Dealing with negative marginal utilities in the discrete choice modeling of labor supply. Economics Letters, 118, 16–18.

Meyer, B. D., & Rosenbaum, D. T. (2001). Welfare, the earned income tax credit, and the labour supply of single mothers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1063–1114.

Nichols, A., & Rothstein, J. (2015). The earned income tax credit (EITC). NBER Working Paper No. 21211.

OECD (2008). Growing unequal. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development.

Oliver, X., & Spadaro, A. (2012). Active welfare state policies and women labour participation in Spain. Presented at the 2nd Microsimulation Workshop 2012, Bucharest.

Pencavel, J. (1987). Labour supply of men. In O. Ashenfelter, & R. Layard (Eds.), Handbook of labour economics, Vol. I (pp. 3–102). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Saez, E. (2002). Optimal income transfer programs: intensive versus extensive labour supply responses. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 1039–1073.

Sánchez-Mangas, R., & Sánchez-Marcos, V. (2008). Balancing family and work: the effect of cash benefits for working mothers. Labour Economics, 15, 1127–1142.

Sanmartín, J. (2007). El efecto de los cambios en los tipos marginales sobre la base imposible del IRPF. Hacienda Pública Esp, 182, 9–27.

Scholz, J. K. (1996). In-work benefits in the United States: the earned income tax credit. The Economic Journal, 106, 156–169.

Selin, H. (2014). The rise in female employment and the role of tax incentives. An empirical analysis of the Swedish individual tax reform of 1971. International Tax and Public Finance, 21, 894–922.

Sutherland, H. (2007). EUROMOD: the tax-benefit microsimulation model for the European Union. In A. Gupta, & A. Harding (Eds.), Modelling our future: population ageing, health and aged care, Vol. 16. International Symposia in Economic Theory and Econometrics. Oxford: Elsevier.

Sutherland, H., & Figari, F. (2013). EUROMOD: the European Union tax-benefit microsimulation model. International Journal of Microsimulation, 6, 4–26.

Van Soest, A. (1995). Structural models of family labour supply. A discrete choice approach. The Journal of Human Resources, 30, 63–88.

Acknowledgements

We thank María Arrazola, Olga Cantó, Stacy Dickert-Conlin, Xisco Oliver, Jorge Onrubia, Raul Ramos, Jesús Ruiz-Huerta, three anonymous referees and the editor and many seminar participants at Alicante, Atlanta, Bucharest, Dublin, Girona, and Madrid for their helpful discussions and comments. Financial support for this research was provided by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (ECO2016-76506-C4-3-R) and Comunidad de Madrid (S2015/HUM3416). The results presented here are based on EUROMOD version G4.0 and Spanish ECV 2014. EUROMOD is maintained, developed and managed by the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) at the University of Essex, in collaboration with national teams from the EU member states. We are indebted to the many people who have contributed to the development of EUROMOD. The process of extending and updating EUROMOD is financially supported by the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation “Easi” (2014-2020). The results and their interpretation are the authors’ responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ayala, L., Paniagua, M. The impact of tax benefits on female labor supply and income distribution in Spain. Rev Econ Household 17, 1025–1048 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-018-9405-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-018-9405-5