Abstract

This paper examines empirical links between sexual orientation and self-reported lying using data collected in several waves of Georgia Institute of Technology’s World Wide Web Users Survey. The data include questions about sexual orientation, lying in cyberspace, and a broad range of demographic information. According to the theoretical framework of Gneezy (Am Econ Rev 95: 384–395, 2005) on the economics of deception, individuals conceal or falsify information when the expected benefit of lying exceeds its costs in terms of psychic disutility. If non-heterosexuals expect to benefit more by falsifying information, then this theory predicts higher rates of lying among non-heterosexuals. The data show that gays and lesbians do indeed report lying more often than heterosexuals, both unconditionally in bivariate correlations and after controlling for demographic and geographic differences. These empirical results are consistent with the conclusion that non-heterosexuals expect higher benefits from concealing personal information because of anti-homosexual discrimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The literature on the psychology of heuristics (Gigerenzer et al. 1999) is rich with alternative models in which decision makers do not weigh costs and benefits at all, but rather employ simple strategies to deal with commonly encountered tasks such as taking a survey or, for homosexuals, choosing whether to conceal sexual orientation depending on contextual cues in the environment.

Grignon et al. (2006) use the linear probability model to estimate the effect of free health care programs on the probability of utilizing healthcare, arguing that the interpretation of fixed effects is superior to that obtained by logit or probit models, despite the disadvantages of heteroskedasticity and probability estimates that can lie outside the unit interval. Similarly, Drago et al. (2008) argue that measurement of fixed effects (or dummy variables) can be better accomplished with the linear probability model than with logit and probit models.

See http://gvu.cc.gatech.edu/what/websurveys.php for details.

The Wave-7, Wave-8 and Wave-9 sample item asked: “Some websites ask for you to register with the site by providing personal information. When asked for such information, what percent of the time do you falsify the information?” The response choices were: “I’ve never falsified information,” “Under 25% of the time,” “26–50% of the time,” “51–75% of the time,” or “over 75% of the time.” From this list of valid responses, a binary variable measuring self-reported lying was constructed. All estimated models reported below use two fixed effect dummies for Wave-8 and Wave-9 survey respondents and are reproducible using ordered categorical probability models that utilize the rest of the measurable variation in self-reported lying but suffer from the disadvantage of more cumbersome marginal effects.

Non-heterosexual sexual orientation is a binary indicator equal to one for individuals who self-report their sexual orientation as something other than heterosexual. The survey item states: “Note: Although this is a sensitive question, the answer can help Internet developers to understand the needs of current Web users. It is not intended to offend. How would you classify yourself?” Valid responses are: “None of your business!,” “Heterosexual,” “Gay Male,” “Lesbian,” “Bisexual” and “Transgender.” Any of the last four of these valid responses maps into the category “non-heterosexual.” Around 5% said that sexual orientation was “None of your business!” These non-responders were eliminated from the sample and are not considered outside of Appendix B, which discusses the empirical correlates of item non-response.

Another, potentially more troubling, possibility is that respondents in the Georgia Tech Survey were disproportionately white relative to the broader population of volunteer online survey respondents. We have no data to reliably cross-validate the demographics in our sample against reliable population characteristics of online survey respondents. Broader interpretations of our model’s results depend on the maintained assumption of representativeness, defined narrowly with respect to the population of online survey respondents.

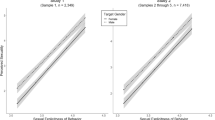

The test statistic for the null hypothesis that gays and straights have identical regressions (of lying on Age and Age-squared while controlling for all other variables in the model presented in Table 2) is distributed as F(3, 18591) for men and F(3, 9348) for women, with observed p-values of 0.044 and 0.000, respectively.

References

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80, 123–129. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(03)00032-6.

Allegretto, S., & Arthur, M. (2001). An empirical analysis of homosexual/heterosexual male earnings differentials: Unmarried and unequal? Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 54(3), 631–646. doi:10.2307/2695994.

Alm, J., Badgett, M. V. L., & Whittington, L. A. (2000). Wedding bell blues: The income tax consequences of legalizing same-sex marriage. National Tax Journal, 53(2), 201–214.

Badgett, L. M. V. (1995). The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 48(4), 726–739. doi:10.2307/2524353.

Badgett, L. M. V. (2001). Money, myths, and change: The economic lives of lesbians and gay men. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berg, N. (2005). Non-response bias. In Kempf-Leonard, K. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social measurement (vol. 2, pp. 865–873). London: Academic Press.

Berg, N., & Lien, D. (2006). Same-sex sexual behavior: U.S. frequency estimates from survey data with simultaneous misreporting and non-response. Applied Economics, 38(7), 757–769. doi:10.1080/00036840500427114.

Berg, N., & Lien, D. (2002). Measuring the effect of sexual orientation on income: Evidence of discrimination? Contemporary Economic Policy, 20, 394–414. doi:10.1093/cep/20.4.394.

Black, D., Gates, C., Sanders, S., & Taylor, L. (2002). Why do gay men live in San Francisco? Journal of Urban Economics, 51, 54–76. doi:10.1006/juec.2001.2237.

Black, D. A., Makar, H. R., Sanders, S. G., & Taylor, L. (2003). The effects of sexual orientation on earnings. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 56(3), 449–469. doi:10.2307/3590918.

Bloom, D. E., & Glied, S. (1992). Projecting the number of new AIDS cases in the United States. International Journal of Forecasting, 8(3), 339–365. doi:10.1016/0169-2070(92)90052-B.

Chauncey, G. (1994). Gay New York: Gender, urban culture, and the making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. New York: Basic.

Cox, D. R. (1970). The analysis of binary data. London: Methuen.

Demichelis, S., & Weibull, J. W. (2006). Efficiency, communication and honesty, SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance No. 645.

Drago, F., Galbiati, R., & Vertova, P. (2008). Prison conditions and recidivism, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) Working Paper 3395.

Dreber, A., & Johannesson, M. (2008). Gender differences in deception. Economics Letters, 99(1), 197–199. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2007.06.027.

Gigerenzer, G., Todd, P. M., & The ABC Research Group. (1999). Simple heuristics that make us smart. New York: Oxford University Press.

Grignon, M., Perronnin, M., & Lavis, J. N. (2006). Does free supplementary health insurance help the poor to access health care?: Evidence from France, CHEPA Working Paper, McMaster University.

Gneezy, U. (2005). Deception: The role of consequences. The American Economic Review, 95(1), 384–394. doi:10.1257/0002828053828662.

Fischbacher, U. & Heusi, F. (2007). Lies in disguise, an experimental study on cheating, TWI Working Paper.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class. New York: Basic Books.

Hurkens, S., & Kartik, N. (2006). (When) would I lie to you? Comment on “Deception: The role of consequences,” Unitat de Fonaments de l’Anàlisi Econòmica (UAB) and Institut d’Anàlisi Econòmica (CSIC) Working Paper.

Mazar, N., Ariely, D. (2006). Dishonesty in everyday life and its policy implications. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 25(1), 1–25.

Miettinen, T. (2006). Promises and conventions: An approach to pre-play agreements, Working Paper.

Murray, S. O. (1999). Homosexualities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Plug, E., & Berkhout, P. (2004). Effects of sexual preferences on earnings in the Netherlands. Journal of Population Economics, 17, 117–131.

Sanchez-Pages, S., & Vorsatz, M. (2006). Enjoy the silence: An experiment on truth-telling, University of Maastricht Working Paper.

Turner, H. A. (1999) Participation bias in AIDS-related telephone surveys: Results from the National AIDS Behavioral Survey (NABS) non-response study. The Journal of Sex Research, 36, 52–66.

Wang, J. T., Spezio, M., & Camerer, C. F. (2006). Pinocchio’s Pupil: Using eyetracking and pupil dilation to understand truth-telling and deception in games, Cal-Tech Working Paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Logit model of self-reported lying

Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Coeff | t | Coeff | t | |

Non-Heterosexual | −0.255 | −0.5 | 1.326 | 1.4 |

Age | −0.104 | −11.2 | −0.065 | −4.5 |

Age-Squared | 0.001 | 5.5 | 0.000 | 1.8 |

Age × Non-Heterosexual | 0.013 | 0.5 | −0.036 | −0.6 |

Age-Squared × Non-Heterosexual | 0.000 | −0.2 | 0.000 | 0.2 |

Years On Internet | 0.245 | 14.1 | 0.205 | 8.5 |

Completed High School | −0.443 | −1.7 | −0.659 | −1.6 |

Some College | 0.100 | 1.5 | 0.105 | 1.1 |

Completed College | 0.100 | 2.6 | 0.110 | 2.0 |

Completed Graduate Degree | −0.006 | −0.1 | 0.165 | 2.5 |

Works in Software or Computer Biz | 0.267 | 4.6 | 0.290 | 3.9 |

Works in Education | −0.027 | −0.4 | −0.073 | −1.0 |

Works as a Manager | 0.105 | 1.6 | 0.067 | 0.8 |

Works as Other Professional | 0.031 | 0.5 | 0.066 | 0.9 |

Non-Windows OS User (Mac/Linux) | −0.005 | −0.1 | 0.010 | 0.2 |

Disabled | −0.016 | −0.2 | 0.024 | 0.3 |

Household Income in $1000 units | 0.001 | 0.9 | 0.001 | 0.7 |

Native Language Non-English | −0.036 | −0.5 | 0.074 | 0.5 |

Asian | −0.222 | −2.3 | 0.115 | 0.7 |

Black | −0.124 | −0.9 | −0.031 | −0.2 |

Hispanic | −0.135 | −1.1 | −0.087 | −0.5 |

Latino but not Hispanic | −0.109 | −0.5 | 0.362 | 1.1 |

Indigenous Person | 0.458 | 1.9 | 0.494 | 1.5 |

Other Race | 0.057 | 0.5 | −0.148 | −0.8 |

Africa | −0.183 | −0.8 | −1.087 | −1.4 |

Asia | 0.285 | 1.8 | 0.252 | 0.8 |

Canada | 0.047 | 0.7 | −0.025 | −0.2 |

Central America | −2.123 | −2.9 | −0.919 | −0.8 |

Europe | 0.226 | 3.0 | 0.089 | 0.6 |

Middle East | 0.249 | 0.9 | 0.664 | 1.4 |

Oceania | −0.159 | −1.7 | 0.314 | 2.1 |

South America | −0.776 | −3.5 | −2.037 | −1.9 |

West Indies | −0.118 | −0.3 | 0.776 | 0.9 |

8th-Wave Survey | 0.093 | 2.3 | 0.206 | 3.6 |

9th-Wave Survey | 0.286 | 7.4 | 0.242 | 4.4 |

Constant | 2.084 | 6.7 | 0.905 | 1.9 |

p-Value for H0: Non-Hetero coeffs = 0* | 0.026 | 0.000 | ||

Pseudo R 2 | 0.0957 | 0.0575 | ||

Unconditional rate of self-reported lying | 0.430 | 0.325 | ||

Sample Size | 18,597 | 9,354 | ||

Appendix B

Previous work emphasizes the importance of jointly accounting for misreporting and non-response when using data with self-reported sexual orientation (Berg 2005; Berg and Lien 2006). This appendix provides additional detail on how the data were cleaned and how item non-response correlates with important demographic characteristics.

Recall that the data consists of three waves of surveys. These data contain responses from a total of 34,498 individuals aged 19 and older, but only 27,951 provided valid responses to all variables used in the empirical model. The other 6,547 (=34,498 − 27,951) individuals non-responded to at least one sample item, raising the question of systematic inclusion or exclusion from the sample due to correlations between the event of non-response and other variables in the model.

There were two non-response possibilities for the dependent variable regarding the frequency of falsifying information: those who left the item blank, referred to as “Not Say;” and those who responded that the question was “Not Applicable,” perhaps because these responders never faced a website that requested personal information. Eliminating these invalid dependent-variable responses led to 3,913 individuals being dropped. These individuals are not included in any of the reported results here, and the “non-responders” label is defined to refer only to respondents who have a valid dependent variable observation but at least one missing response among the other variables in the empirical model listed in Table 1.

Rates of lying are 0.395 among responders and 0.421 among non-responders, are not very different. Regarding rates of self-reported sexual orientation, only 28.1% of those in the non-responder category non-responded to the sexual orientation sample item. Among the 71.9% of non-responders who did provide a valid response to the sexual orientation sample item (but non-responded to a sample item other than the sexual orientation), 5/71.9 = 7.0% report their status as non-heterosexual, roughly 1 percentage point lower than the responder sample.

The sample item with the highest rate of non-response was Household Income, with 70.1% of non-responders having left this item blank. Average Household Income among non-responders with a valid Household Income response is $42,730, which is significantly lower than mean Household Income among responders. Other interesting correlations are as follows. Those who work in education are more likely to non-respond, as are those whose native language is non-English. Those who report having a disability are more than twice as likely to be non-responders. More than 11% of non-responders refused to identify their ethnicity, although a large majority of both responders and non-responders who did provide ethnicity are white. Few systematic differences in geography between responders and non-responders were apparent, and both groups are roughly 60% male.

As for why non-responders choose to non-respond, there is one survey item that provides some information. Respondents were asked to choose from a list of 15 issues which was the “most important issue facing the Internet.” Privacy concerns are noticeably higher among non-responders, with 33% of non-responders versus 26% of responders saying that privacy is the most important issue facing the Internet.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berg, N., Lien, D. Sexual orientation and self-reported lying. Rev Econ Household 7, 83–104 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-008-9038-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-008-9038-1