Abstract

This paper uses the concept of a computer as a public good within the household to model the demand for computers at home. It also investigates the determinants, and consequences for earnings, of computer use. The equations are estimated using data on the native born and immigrants from the 2001 Census of Population and Housing in Australia. The multivariate analyses show that recent arrivals are more likely to use computers than the Australian born. The data suggests a high degree of favorable selection in migration as the level of computer use in Australia is much higher than in most of the countries that Australia’s immigrants come from. Those with a higher permanent income (education, household assets) are more likely to have a computer at home, but there is no effect of transitory income (unemployment). Immigrants who are more proficient in English are also more likely to use a computer. The relation between age and computer use is strongly influenced by cohort effects. Using a computer at home is associated with about 7% and 13% higher earnings for native-born and foreign-born men, respectively. For the immigrants, the effects of schooling and English language proficiency on earnings are greater among those who use a computer at home. This suggests complementarity in the labor market. The use of a computer is shown to be a way the foreign born can increase the international transferability of their pre-immigration skills, a finding that has implications for immigrant assimilation policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The conceptual framework recognizes that it may be proficiency in the dominant language of the internet (English) that matters more than the official language of the destination country. However, as the empirical analyses are conducted for an English-speaking country, Australia, the relative importance of this distinction cannot be determined.

The analyses presented build upon examination of the impact that computer use has on wages by Krueger (1993) and Goss and Phillips (2002) for the US, Daldy and Gibson (2003) for New Zealand, Miller and Mulvey (1997a) for Australia, Dolton and Makepeace (2004) for the UK, and DiNardo and Pischke (1997) for Germany.

This favorable selectivity may result from favorable self-selectivity on the part of the migrants (the supply side) and/or from selectivity in the rationing or allocation of visas (the demand side for immigrants). The latter form of selectivity should be more important in Australia than in the US, given Australia’s use of a skills-based points system in the selection of many of its immigrants. See Chiswick and Miller (2006) for a review of Australia’s immigration policy relevant to this issue. In particular, this paper sets out the point system used in immigrant selection at the present time, and highlights the major changes in this since its inception.

The model outlined here could be extended to include the paternalism of those with resources, or decision-making power, towards those without resources or direct involvement in household decision making. The demand for computers should vary directly with the degree of paternalism towards children, ceteris paribus.

The male householder is used as the reference person in this exposition to correspond to the empirical analysis, which focuses on adult males.

The RADL is an on-line database query system, under which microdata are held on a server at the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in Canberra. Registered users are able to submit programs (e.g., SAS, SPSS) to interrogate, analyze, model, etc. the data. See ABS (2003) for details.

There were 55,883 males in the 20–64 years age bracket prior to the exclusion of observations with missing values of variables used in the analysis. Missing values are not imputed in the Australian Census Microdata file as they are for the U.S. Census.

For the birthplace categories included in Table 1, the simple correlation coefficient between computer and internet use is .99. At the level of the individual, a simple cross-tabulation of computer use by internet use shows that 85.3% of adult males were in the same classification (user or non-user) for computer use as they were for internet use. The relationship would be even stronger if the questions were for computer/internet use last month instead of last week.

These data were extracted from the CIA World Factbook 2003. The relevant comparison data are presented in Appendix D.

The partial effect for a continuous variable in the logit model can be calculated by the formula: \({\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial Z}=\rho(1-\rho)\widehat{\beta}}\), where ρ is the probability of computer use in the data set for each particular model and \({\widehat{\beta}}\) is the estimated coefficient for the variable Z. The partial effects discussed in the text have been computed at the sample mean value of ρ.

Figure 1 presents only the probability for the total sample since there are no apparent differences between the Australian born and the overseas born in the education-computer use relationship.

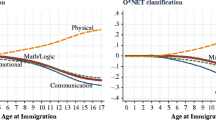

As age = age at migration + years since migration, the partial effect evaluated here of the impact of a change in age at migration, holding years since migration constant, must allow age to vary. Given this linear relationship, other partial effects can be computed from the estimates, such as the impact on computer usage of age at migration, holding age constant (which must allow years since migration to vary). Only the former magnitude is considered in the text.

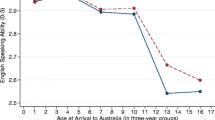

The estimates used for the foreign born in Fig. 2 are from the model without birthplace fixed effects. Controls for birthplace fixed effects have virtually no effect on the age-computer relationship.

Arabsheibani et al. (2004) report that a married person is more likely to use a computer, though the impact was not statistically significant. This may have arisen because no account was taken of the spouse’s education level.

Thus, adults may acquire a computer if their own teenage children are living at home, but not if aged parents live with them. Other family public goods may be in greater demand in the presence of aged relatives.

Miller and Mulvey (1997b) also find that those who had more limited English skills are less likely to use computers in the Australian labor market.

Miller and Mulvey (1997b) and DiNardo and Pischke (1997) contend that full-time workers are more likely to use computers than their part-time counterparts. Miller and Mulvey’s (1997b) computer usage variable includes anyone who had ever used a computer, while the DiNardo and Pischke (1997) measure was for on-the-job computer usage.

Males aged 20–64 who are not in the labor force are likely to be full-time students (12%), disabled, or early retirees (40% of those not in the labor force are aged 55–64).

As noted above, these measures of wealth, together with educational attainment and labor force participation, are likely to be better measures for the income effect on the demand for computers than labor market earnings last week. Other variables the same, earnings last week would measure the effect of transitory income. Earnings could reflect a price effect on the demand for computers, if those with higher earnings have a higher value of time in consumption activities and computers are substituted for more time-intensive home production activities. When the natural logarithm of weekly earnings was included as a regressor, its estimated impact was not statistically significant for either the total, Australian-born or native-born samples. In this analysis, those with zero or negative earnings were assigned a value of −log(2). This essentially linearizes the natural logarithmic function around 1.

Given the similarities between Australia and New Zealand, the low cost of migration, and the free (unrestricted) mobility between the two countries, New Zealanders in Australia are more like internal migrants than international migrants.

A significant negative effect of spouse’s education on computer usage is found only for the small sample of immigrants from Africa (162 observations). The reasons for this atypical finding are unclear.

These findings are in accordance with the results of Miller and Mulvey (1997a), who reported wage penalties of 7 and 18% for those who have some difficulties and extreme difficulties with the English language, respectively. Similarly, Chiswick and Miller (1985) report a wage penalty for immigrants in Australia of 11% for those who speak a language other than English at home, with the earnings of individuals who have poor mastery over the English language being a further 4% lower.

In this paper, the percentage impact on wages is calculated using 100[exp (estimate)−1] (see Halvorsen & Palmquist, 1980) for those estimates that are greater than .1, whereas all the remaining estimates will be interpreted as percentage effects.

In 2001 the Australian dollar was equivalent to approximately .5 US dollars. It is currently (2005) around .75 US dollars.

Dustmann and van Soest’s (2001) findings regarding the effect of language proficiency on immigrant earnings imply that correlated unobserved heterogeneity in earnings and computer use will result in an upward bias in the IV estimates.

A similar interaction term was insignificant when included in the estimating equation for the native born.

This is comparable to the apparent complementarity effect on earnings of English language proficiency and other human capital (schooling and experience) in Canada (Chiswick & Miller, 2003).

References

Arabsheibani, G. R., Emami, J. M., & Marin, A. (2004). The impact of computer use on earnings in the UK. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 51(1), 82–94.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2003). Technical Paper: Census of Population and Housing Household Sample File Australia 2001, Catalogue No. 2037.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

Baker, M., & Benjamin, D. (1994). The performance of immigrants in the Canadian labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 12(3), 369–405.

Buchinsky, M. (1998). Recent advances in Quantile Regression Models: A practical guideline for empirical research. Journal of Human Resources, 33(1), 88–126.

Chiswick, B. R. (1977). Sons of immigarnts: Are they at an earnings disadvantage?. American Economic Review, 67(1), 376–380.

Chiswick, B. R. (1978). The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. Journal of Political Economy, 86(5), 897–922.

Chiswick, B. R. (1999). Are immigrants favorably self-selected? American Economic Review, 89(2), 181–185.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (1985). Immigrant generation and income in Australia. Economic Record, 4(2), 168–192.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (1995). The endogeneity between language and earnings: An international analysis. Journal of Labor Economics, 13(2), 246–288.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (1998). The economic cost to native-born Americans of limited English language proficiency, Report Prepared for the Center for Equal Opportunity, available http://www.ceousa.org/earnings.html

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2003). The complementarity of language and other human capital: Immigrant earnings in Canada. Economics of Education Review, 22, 469–480.

Chiswick B. R., & Miller P. W. (2005) Linguistic distance: a quantitative measure of the distance between English and other languages. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 26(1), 1–11.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2006). Immigration to Australia during the 1990s: Institutional and labour market influences. In: Deborah Cobb-Clark, Siew-Ean Khoo (eds), Public Policy and Immigrant Settlement. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 121–148.

Daldy, B., & Gibson, J. (2003). Have computers changed the New Zealand wage structure? Evidence from data on training? New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 28(1), 13–21.

DiNardo, J.E., & Pischke, J. (1997). The returns of computer use revisited: Have pencils changed the wage structure too? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1), 291–303.

Dolton, P., & Makepeace, G. (2004). Computer use and earnings in Britain. The Economic Journal, 114, C117-C129.

Dostie, B., Jayaraman, R., & Trépanier, M. (2006). The returns to computer use revisited, Again. IZA Discussion Paper No. 2080, IZA, Bonn.

Dustmann C., & van Soest A. (2001). Language fluency and earnings: Estimation with misclassified language indicators. Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(4), 663–674.

Fry, R., & Lowell, B. L. (2003). The value of bilingualism in the US labor market. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 57(1), 128–140.

Goss, E. P., & Phillips, J. M. (2002). How information technology affects wages: Evidence using internet usage as a proxy for IT skills. Journal of Labor Research, 23(3), 463–474.

Halvorsen, R., & Palmquist, R. (1980). The interpretation of dummy variables in semilogarithmic equations. American Economic Review, 70(3), 474–475.

Krashinsky, H. A. (2004). Do marital status and computer usage really change the wage structure? Journal of Human Resources, 39(3), 774–791.

Krueger, A. B. (1993). How computers have changed the wage structure: Evidence from Microdata, 1984–1989. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(1), 33–60.

Liu, J. T., Tsou, M. W., & Hammitt, J. K. (2004). Computer use and wages: Evidence from Taiwan. Economics Letters, 82(1), 43–51

Martins, P., & Pereira, P. (2004). Does education reduce wage inequality? Quantile regression evidence from 16 countries. Labour Economics, 11(3), 355–371.

Miller, P. W., & Mulvey, C. (1997a). Computer skills and wages. Australian Economic Papers, 36(68), 106–113.

Miller, P. W., & Mulvey, C. (1997b). Computer usage among Australian workers. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 1(1), 25–47.

Miller, P. W., & Neo, L. M. (2003). Labour market flexibility and immigrant adjustment. Economic Record, 79(246), 336–356.

Puhani, P. A. (2000). The Heckman correction for sample selection and its critique. Journal of Economic Surveys, 14(1), 53–68.

Stolzenberg, R. M., & Relles, D. A. (1997). Tools for intuition about sample selection bias and its correction. Amerian Sociology Review, 63, 493–507.

Acknowledgements

We thank Derby Voon for research assistance, and Henriette Engelhardt, participants at the Midwest Economics Association March 2006 Annual Meeting (Chicago), the Vienna Institute of Demography Seminar May 2006, and the European Society for Population Economics Annual Meeting (Verona), June 2006, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments. Chiswick acknowledges research support from the Institute of Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois. Miller acknowledges financial assistance from the Australian Research Council. Part of the research for this paper was conducted while both authors were visitors at IZA-Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The appendices cited in this article are available from the authors upon request.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chiswick, B.R., Miller, P.W. Computer usage, destination language proficiency and the earnings of natives and immigrants. Rev Econ Household 5, 129–157 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-007-9007-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-007-9007-0