Abstract

The paper tests the hypothesis that private transfers can be explained by the existence of self-enforcing family constitutions prescribing the minimum level at which a person in middle life should support her young children and elderly parents. The test is based on the effect of a binding credit ration on the probability of making a money transfer, which can be positive only in the presence of family constitutions. Allowing for the possible endogeneity of the credit ration, we find that rationing has a positive effect on the probability of giving money if the potential giver is under the age of retirement, but no significant effect if the person is already retired. This appears to reject the hypothesis that transfer behavior is the outcome of unfettered individual optimization on the part of either altruistic or exchange motivated agents, but not the one that individuals optimize subject to a self-enforcing family constitution. The policy implications are briefly discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The results of the second wave were only just becoming available at the time of writing.

Under the strong assumption of income pooling, the two marginal effects should add up to unity. No empirical study has ever found that (see, for example, Altonji, Hayashi, & Kotlikoff, 1995).

If it did, there would be no point in distinguishing between goods that money can buy, and personal services supplied by a family member. An elderly person who regards the services of a paid nurse as a perfect substitute for those of a grown-up daughter is in fact indifferent between receiving an hour of her daughter’s time, or a sum of money sufficient to hire a nurse for an hour.

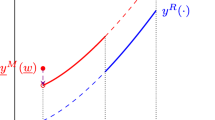

For a full exposition, see Cigno (2006).

According to the economic theory of constitutions (Buchanan, 1987), it may be in the interest of a group of agents to first agree on certain basic rules, that will permit them to safely renounce the dominant strategy in a prisoner’s dilemma type of situation, and then optimize subject to those rules.

This cost is fixed in the usual sense that it does not depend on the level of activity, in this case on the number children, and thus on how much the agent will receive from them in old age.

That, notice, is not the same as actually paying for those services as in the exchange model. In the constitution model, the old have already paid for what they are getting, and any money they might give their grown-up children will be a gift.

A system is said to be actuarially fair if the expected value of the benefits at the time of retirement equals the capitalized value of the contributions made. Therefore, an actuarially fair scheme does not alter the wealth position of those who participate in it.

Except for the distortion of marginal incentives if pension contributions increase with labor.

Indeed, if it were at least in part an entitlement to receive personal services without perfect market substitutes from a grown-up child, that could well be of great value to the child’s parent, but of little use to a third party such as a bank.

If the agent can comply with the constitution by supplying personal services without a perfect market substitute instead of money, income is to be interpreted as full income, and transfers as the money equivalent of the utility of the person receiving the transfer.

Incidentally, this asymmetry prevented us from exploiting the small panel element contained in this series of surveys.

Furthermore, it does not provide information on assets, and gives income information only in categorical form.

The questionnaire asks about a list of different forms of help given or received, including “economic help”, “help with health matters”, “help with domestic chores”, “help with bureaucratic matters”, and so on. We are classifying as money intensive not only what the questionnaire calls “economic help”, but also “help with health matters”, because that involves direct expenditure on medicines, private nurses, and the like. We classify everything else as time intensive.

Alimony to a former spouse, and mandated support for children living with a former spouse, are explicitly excluded.

The actual questions are: “In the course of 1991, did you or any other member of your household have a loan application rejected or curtailed by a bank or other financial institution?” and “In the course of 1991, did you or any other member of your household consider applying to a bank or other financial institution for a loan, but desisted thinking that the application would be rejected?”.

On average, rationed households transfer more than the rest (449,000 liras, as against 360,500 for the whole sample). If we exclude households not making transfers, however, the mean is lower for rationed households (1,821,000 liras) than in the sample as a whole (2,170,000 liras).

We checked for weakness of the instruments by regressing the rationing variable on the full set of explanatory and instrumental variables, as shown in Table 2, and testing whether the inclusion of the latter could be rejected by an F test. As the F statistics are well above the threshold value of 10 indicated in Bound, Jaeger and Baker (1995), we conclude that our instruments are not weak in a statistical sense.

This is the estimate, in percentage form (the so-called marginal effect), of the coefficient on credit rationing reported in Table 3.

Essentially, that the amount borrowed must not be more that a certain fraction of the market value of the house, and that the monthly repayment must not be higher than a certain fraction of the borrower’s monthly income.

As we are using several instruments for one endogenous variable, we performed an overidentification test (using the “overid” command implemented in STATA) as if the variables “transfer made” and “rationed” were continuous. In the full sample and in the sub-sample with a head still working, the hypothesis of orthogonality between the instruments and the error is only weakly accepted while in the sub-sample of households with a retired head the null of valid instruments is strongly not rejected (at the 1% level). That seems to throw doubt on our choice of instruments where the full sample and the first sub-sample are concerned. However, the overidentification test in question is designed for continuous variables, and it is thus not applicable to dichotomous variables like “transfer made” and “rationed”. Furthermore, since the correlation between the error terms of the two equations is negative, ignoring the endogeneity of the probability of being rationed, leads to an underestimate of the effect of rationing on the probability of making a money transfer. The probit estimates obtained treating the “rationed” variable as exogenous may thus be regarded as lower bounds. As these lower bounds are positive in the case of households with head not retired, and zero in that of household with head retired, the null hypothesis that self-enforcing family constitutions do not exist would then be rejected even if the estimates obtained by the instrumental variables method were not valid.

For the sake of brevity, the first stage results for the probability of being rationed are omitted from Table 4, but are available on request from the authors.

References

Altonji, J. G., Hayashi, F., & Kotlikoff, L. J. (1995). Parental altruism and inter vivos transfers: Theory and evidence. Journal of Political Economy, 105, 1121–1166.

Altonji, J. G., Hayashi, F., & Kotlikoff, L. J. (2000). The effects of income and wealth on time and money transfers between parents and children. In A. Mason & G. Tapinos (Eds.), Sharing the wealth: Intergenerational economic relations and demographic change. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Attias-Donfut, C., & Wolff, F. C. (2000). The redistributive effect of generational transfers. In S. Arber, & C. Attias-Donfut (Eds.), The myth of generational conflict. The family and the state in ageing societies. London: Routledge.

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of social interactions. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 1063–1093.

Bhaumik, S. M., & Nugent, J. B. (2000). Wealth accumulation, fertility, and transfers to to elderly households heads in Peru. In A. Mason, & G. Tapinos (Eds.), Sharing the wealth: Intergenerational economic relations and demographic change. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bound, J., Jaeger, D. A., & Baker, R. M. (1995). Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and endogenous explanatory variables is weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90, 443–450.

Buchanan, J. (1987). Constitutional economics. In The new palgrave: A dictionary of economics. London: MacMillan.

Cigno, A. (1993). Intergenerational transfers without altruism: Family, market and state. European Journal of Political Economy, 7, 505–518.

Cigno, A. (2006). A constitutional theory of the family. Journal of Population Economics, 19, 259–283.

Cigno, A., Casolaro, L., & Rosati, F. C. (2003). The impact of social security on saving and fertility in Germany. FinanzArchiv, 59, 189–211.

Cigno, A., & Rosati, F. C. (1992). The effects of financial markets and social security on saving and fertility behaviour in Italy. Journal of Population Economics, 5, 319–341.

Cigno, A., & Rosati, F. C. (1996). Jointly determined saving and fertility behaviour: Theory, and estimates for Germany, Italy, UK, and USA. European Economic Review, 40, 1561–1589.

Cigno, A., & Rosati, F. C. (1997). Rise and fall of the Japanese saving rate: The role of social security and intra-family transfers. Japan and the World Economy, 9, 81–92.

Cigno, A., & Rosati, F. C. (2000). Mutual interest, self-enforcing constitutions and apparent generosity. In L. A. Gérard-Varet, S. C. Kolm, & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), The economics of reciprocity, giving and altruism. London and New York: MacMillan and St Martin’s Press.

Cox, D. (1987). Motives for private income transfers. Journal of Political Economy, 95, 508–546.

Cox, D., & Jakubson, G. (1995). The connection between public transfers and private interfamily transfers. Journal of Public Economics, 57, 129–167.

Cox, D., & Rank, M. (1992). Inter-vivos transfers and intergenerational exchange. Review of Economics and Statistics, 74, 305–314.

Finch, J. (1989). Family obligations and social change. Oxford: Polity Press.

Foster, A. D., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (2000). Financial intermediation, transfers, and commitment: Do banks crowd out private insurance arrangements in low-income rural areas? In A. Mason, & G. Tapinos (Eds.), Sharing the wealth: Intergenerational economic relations and demographic change. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greenwood, D. T., & Wolff, E. N. (1992). Changes in wealth in the United States, 1962–83. Journal of Population Economics, 5, 261–288.

Guttman, J. M. (2001). Self-enforcing reciprocity norms and intergenerational transfers: Theory and evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 81, 117–151.

ISTAT (1993). Sintesi dei risultati dell’indagine. Indagine Multiscopo sulle Famiglie. Roma: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica

Rosati, F. C. (1996). Social security in a non-altruistic model with uncertainty and endogenous fertility. Journal of Public Economics, 60, 283–294.

Sloan, F. A., & Zhang, H. H. (2002). Upstream intergenerational transfers. Southern Economic Journal, 69, 363–80.

Stark, O. (1995). Altruism and beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wooldridge, J. (2003). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

This paper originates from a suggestion by Donald Cox, and has benefitted from comments by Sonia Bhalotra. Constructive criticism by three anonymous referees helped to greatly improve the paper. Responsibility for remaining errors rests with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cigno, A., Giannelli, G.C., Rosati, F.C. et al. Is there such a thing as a family constitution? A test based on credit rationing. Rev Econ Household 4, 183–204 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-006-0010-7

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-006-0010-7