Abstract

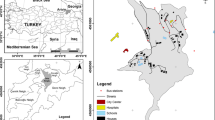

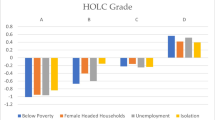

This paper studies the effect of a newly completed highway extension on home prices in the surrounding area. We analyze non-linearities in both the effect of distance from the highway and the effect of time relative to the completion of the road segment. While previous studies of the effects of nearby amenities on property and land values have focused on either cross-sectional spatial or temporal patterns, the joint analysis of the two dimensions has not been thoroughly investigated. We use home sale data from a period of 11 years centered around the completion of a new highway extension in metropolitan Los Angeles. We combine a standard hedonic model with a spline regression technique to allow for non-linear variations of the effect along the temporal and spatial dimensions. Our empirical results show that the maximum home price appreciation caused by the new highway extension occurs at moderate distances from the highway after it is completed. Lower price increases for this period are observed for homes sold closer to the highway or much further away. This price pattern gradually fades away in the years following the construction completion. A similar, although weaker, price pattern is also observed in the first years of the construction period. There is no statistically significant distance dependency in the 2 years in our sample prior to the beginning of the construction. This indicates that the housing market is not fully efficient as the information about the impending construction of the highway is not immediately incorporated into sales prices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Information source: www.sanbag.ca.gov.

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency. The index is set at 100 for 1995 quarter 1.

An alternative to such system estimation is a single regression with interaction terms for the distance spline variables for the eleven 1-year periods. While such pooled model takes advantage of the total set of observations, it also implicitly assumes a constant error variance across all observations. Independent factors that may have been omitted in our model may vary in their strength of the effect on the selling price over time and at different distances; in this case, varying error term variances are more appropriate. Moreover, a possible correlation of the omitted effects over time makes us believe that the seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) methodology employed here is a better candidate than the single regression with interaction terms (or separate regressions for the eleven time subsets).

The analysis of the single regression model tested confirms that the SUR model is superior, as is indicated by lower standard errors, or, alternatively, higher t-statistics, for 60 out of the 77 (or about 78 percent) distance spline variables. The single regression model also appears to capture fewer distance spline effects across the eleven 1-year subsets at statistically significant levels. In addition, unlike the earlier used “global” and the single regression model with the distance-year interaction terms, the SUR methodology gives a high statistical significance (1 percent) to the positive AllRooms coefficient, while at the same time making physical characteristic variables more precise as evidenced from their higher t-statistics. The results of the single regression model are available upon request.

Traffic volume in each direction is calculated by averaging the traffic counts at the new exits of the highway extension in the study area. Data source: California Department of Transportation.

Like in the previous analysis of the spatial distance effects in different time subsets, due to the likely correlation of the omitted variables at different distances from the highway extension we utilize the SUR approach as superior to a single regression with interaction variables or a set of seven independent regressions.

Again, since the coefficients for almost all independent variables maintained their sign and the statistical significance at least at 1 percent level, the regression results for these variables are omitted (available upon request), and Table 7 thus only presents the results for the goodness-of-fit and the time variable coefficients with the corresponding t-statistics.

References

Alonso, W. (1964). Location and land use. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Archer, W. R., Gatzlaff, D. H., & Ling, D. C. (1996). Measuring the importance of location in house price appreciation. Journal of Urban Economics, 40, 334–353.

Bao, H. X. H., & Wan, A. T. K. (2004). On the use of spline smoothing in estimating hedonic housing price models: Empirical evidence using Hong Kong data. Real Estate Economics, 32, 487–507.

Benjamin, J. D., & Sirmans, G. S. (1996). Mass transportation, apartment rent and property values. Journal of Real Estate Research, 12, 1–8.

Bourassa, S. C., Hamelink, F., & Hoesli, M. (1999). Defining housing submarkets. Journal of Housing Economics, 8, 160–183.

Bourassa, S. C., Cantoni, E., & Hoesli, M. (2007). Spatial dependence, housing submarkets, and house price prediction. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 35, 143–160.

Bowes, D. R., & Ihlanfeldt, K. R. (2001). Identifying the impacts of rail transit stations on residential property values. Journal of Urban Economics, 50, 1–25.

Brasington, D. M., & Hite, D. (2005). Demand for environmental quality: a spatial hedonic analysis. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 35, 57–82.

Brown, G. M., & Pollakowski, H. O. (1977). Economic valuation of shoreline. Review of Economics and Statistics, 59, 272–278.

Can, A. (1992). Specification and estimation of hedonic housing price models. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 22, 453–474.

Can, A., & Megbolugbe, I. (1997). Spatial dependence and house price index construction. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 14, 203–222.

Case, B., Clapp, J., Dubin, R., & Rodriguez, M. (2004). Modeling spatial and temporal house price patterns: a comparison of four models. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 29, 167–191.

Debrezion, G., Pels, E., & Rietveld, P. (2007). The impact of railway stations on residential and commercial property value: a meta-analysis. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 35, 161–180.

Dubin, R. A. (1998). Predicting house prices using multiple listings data. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 17, 35–59.

Dubin, R., & Sung, C.-H. (1987). Spatial variation in the price of housing: rent gradients in nonmonocentric cities. Urban Studies, 24, 193–204.

Fik, T. J., Ling, D. C., & Mulligan, G. F. (2003). Modeling spatial variation in housing prices: a variable interaction approach. Real Estate Economics, 31, 623–646.

Gatzlaff, D. H., & Smith, M. T. (1993). The impact of the Miami Metrorail on the value of residences near station locations. Land Economics, 69(1), 54–66.

Gibbons, S., & Machin, S. (2005). Valuing rail access using transport innovations. Journal of Urban Economics, 57, 148–169.

Goodman, A. C. (1978). Hedonic prices, price indexes and housing markets. Journal of Urban Economics, 5, 471–484.

Griliches, Z. (1971). Price indexes and quality change. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Harrison, D., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (1978). Hedonic housing prices and demand for clean-air. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 5, 81–102.

Haurin, D. R., & Brasington, D. (1996). School quality and real house prices: inter- and intrametropolitan effects. Journal of Housing Economics, 5, 351–368.

Hughes, W. T., & Sirmans, C. F. (1992). Traffic externalities and single-family house prices. Journal of Regional Science, 32, 487–500.

Kahn, M. E. (2007). Gentrification trends in new transit-oriented communities: Evidence from 14 cities that expanded and built rail transit systems. Real Estate Economics, 35, 155–182.

Kilpatrick, J. A., Throupe, R. L., Carruthers, J. I., & Krause, A. (2007). The impact of transit corridors on residential property values. Journal of Real Estate Research, 29, 303–320.

Kong, F., Yin, H., & Nakagoshi, N. (2007). Using GIS and landscape metrics in the hedonic price modeling of the amenity value of urban green space: a case study in Jinan City, China. Landscape and Urban Planning, 79, 240–252.

Lafferty, R. N., & Frech, H. E. (1978). Community environment and the market value of single-family homes—effect of the dispersion of land uses. Journal of Law & Economics, 21, 381–394.

Larson, K. L., & Santelmann, M. V. (2007). An analysis of the relationship between residents’ proximity to water and attitudes about resource protection. The Professional Geographer, 59, 316–333.

Leech, D., & Campos, E. (2003). Is comprehensive education really free?: a case-study of the effects of secondary school admissions policies on house prices in one local area. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A-Statistics in Society, 166, 135–154.

Mahan, B. L., Polasky, S., & Adams, R. M. (2000). Valuing urban wetlands: a property price approach. Land Economics, 76, 100–113.

Marsh and Cormier. (2001). Spline regression models. Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, series no. 07–137. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Matthews, J. W., & Turnbull, G. K. (2007). Neighborhood street layout and property value: the interaction of accessibility and land use mix. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 35, 111–141.

McMillen, D. P., & McDonald, J. (2004). Reaction of house prices to a new rapid transit line: Chicago’s Midway Line, 1983–1999. Real Estate Economics, 32, 463–486.

Mikelbank, B. A. (2004). Spatial analysis of the relationship between housing values and investments in transportation infrastructure. Annals of Regional Science, 38, 705–726.

Mikelbank, B. A. (2005). Be careful what you wish for: the house price impact of investments in transportation infrastructure. Urban Affairs Review, 41, 20–46.

Muth, R. E. (1969). Cities and housing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nelson, J. P. (1978). Residential choice, hedonic prices, and demand for urban air-quality. Journal of Urban Economics, 5, 357–369.

Plaut, P. O., & Plaut, S. E. (1998). Endogenous identification of multiple housing price centers in metropolitan areas. Journal of Housing Economics, 7, 193–217.

Rosen, S. (1974). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: product differentiation in pure competition. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 34–55.

Smersh, G. T., & Smith, M. T. (2000). Accessibility changes and urban house price appreciation: a constrained optimization approach to determining distance effects. Journal of Housing Economics, 9, 187–196.

Song, Y., & Knaap, G. J. (2003). New urbanism and housing values: a disaggregate assessment. Journal of Urban Economics, 54, 218–238.

Waddell, P., Berry, B. J. L., & Hoch, I. (1993). Residential property values in a multinodal urban area: new evidence on the implicit price of location. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 7, 117–141.

Yiu, C. Y., & Wong, S. K. (2005). The effects of expected transport improvements on housing prices. Urban Studies, 42, 113–125.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the helpful comments of the participants of the 2008 American Real Estate Society annual conference. We also thank the Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activities program of the California State University for providing us with the funds necessary to purchase the data used for this study.

We would also like to thank Torto Wheaton Research for sponsoring the prize that the paper won for best paper in the Market Analysis category at the 2008 American Real Estate Society annual conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chernobai, E., Reibel, M. & Carney, M. Nonlinear Spatial and Temporal Effects of Highway Construction on House Prices. J Real Estate Finan Econ 42, 348–370 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-009-9208-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-009-9208-9