Abstract

We study whether firms that are led by chief executive officers (CEOs) with law degrees (lawyer CEOs) have different credit ratings and costs of debt from other firms. Our sample consists of Standard & Poor’s 1500 firms from 1992 to 2020, 9.2% of which have lawyer CEOs. We find that these firms have better credit ratings, compared to other firms. On average, their cost of debt is 10% lower than that of firms led by CEOs without legal backgrounds. Our results are robust to different specifications, sampling methods, and controls, such as firm and CEO characteristics. We identify two ways that CEO expertise translates into higher credit ratings: lawyer CEOs are associated with a lower future volatility of stock returns and a reduction in information risk. The decreased business risk and better financial reporting are associated with 5% lower auditing fees for firms with lawyer CEOs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A recent stream of literature finds that CEO characteristics, such as educational background and other personal characteristics, have a significant impact on corporate policies. This literature started with the seminal paper of Bertrand and Schoar (2003), who investigate whether managerial fixed effects matter for corporate decisions. They find that executives from earlier birth cohorts act more conservatively and that managers who hold MBA degrees follow more aggressive strategies. Bertrand and Schoar’s work led to several studies on the effect of managerial characteristics on firm behavior. For example, Malmendier et al. (2011) find that chief executive officers (CEOs) who grew up during the Great Depression avoid debt and lean excessively on internal finance and that CEOs with military experience pursue more aggressive policies, including heightened leverage. Another example is the study of Cronqvist and Yu (2017), who find that, when a firm’s CEO has a daughter, its corporate social responsibility rating (CSR) is about 9.1% higher, compared to the median firm.Footnote 1

We focus on the relation between CEOs’ legal expertise and their firms’ credit ratings. The legal expertise of CEOs is important. Law school classroom experience has a lifelong effect on graduates and is likely to shape their managerial style. Executives with legal training also tend to follow more conservative corporate policies. According to Standard and Poor’s (2002), a firm’s credit rating reflects a ratings agency’s opinion of the entity’s overall creditworthiness in terms of its capacity to satisfy its financial obligations. Credit ratings are considered by both academics and practitioners as one of the primary indicators of a firm’s credit risk (Kisgen 2007; Kuang and Qin 2013). The seminal paper of Graham and Harvey (2001, p. 211) argues that credit rating is the second most important concern in the debt policy of firms: “firms are very concerned about their credit ratings (rating of 2.46, the second most important debt policy factor), which can be viewed as an indication of concern about distress.”Footnote 2

A stream of literature focuses on the roles of firm characteristics and accounting information in the credit rating process.Footnote 3 However, this literature has not considered the role of the CEO in this process. CEOs set the tone at the top and therefore matter for credit risk. We hypothesize that CEOs with a legal background are associated with better credit ratings and lower costs of debt. The reason behind this hypothesis is that CEOs’ legal training will help them facilitate corporate transparency and risk management when assessing their firms’ credit risk.

We find that around 9.2% of the firms in our sample of Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 1500 firms over the period from 1992 to 2020 were run by lawyer CEOs. Consistent with our expectations, we document that these firms have more favorable credit ratings than their peers. These results are robust to different specifications, sampling methods, and controls, such as firm and CEO characteristics, the presence of a general counsel on the senior investment team, and year and firm fixed effects.

The documented effect of CEO legal training on firms’ credit risk could suffer from an omitted variable bias. For example, firms could appoint lawyer CEOs based on certain firm characteristics, and these characteristics could simultaneously influence a firm’s credit risk assessment. We use a number of identification strategies to rule out potential endogeneity concerns. First, we control for firm fixed effects in all regressions to account for time-invariant firm-specific omitted variables. Second, to mitigate concerns that omitted firm or performance characteristics drive our results, we implement an identification strategy based on CEO turnover. Specifically, we examine whether CEO turnover is associated with changes in firm credit ratings by tracing cases of CEO turnover in which we can identify a change in legal education between the new and old CEOs. We find that the appointment of a lawyer CEO enhances a firm’s credit rating, whereas the firm’s credit rating declines when such a CEO is replaced by one without legal training. The same picture emerges when we study CDS spreads, which proxy for credit risk: a firm’s CDS spreads reduce following the appointment of a lawyer CEO, whereas they increase when a lawyer CEO is replaced by a nonlawyer CEO. Third, to ensure the robustness of our results, we employ alternative measures of credit ratings and credit risk, consider alternative model specifications, and conduct sensitivity analyses.

To show that the effect of lawyer CEOs on credit ratings is driven by a reduction in credit risk and not by the CEOs’ undue influence on the rating agencies, we conduct two tests. First, we study the direct impact of credit risk on the firm’s market-based assessment by examining whether lawyer CEOs matter in the pricing of debt capital. We consider all new nonconvertible issue fixed-rate corporate bonds issued and find that firms led by lawyer CEOs, on average, have about 10%, about 19 basis points (bps), lower costs than similar firms headed by nonlawyers. Second, we consider the alternative economic bonding hypothesis that the negotiating power of lawyer CEOs leads to more favorable credit ratings but find no confirmation for it.

An important question is to identify how the legal expertise of CEOs translates into lower credit risk. We isolate and test two possible explanations: reduction in future firm risk and improvement in reporting transparency and information asymmetry. We show that lawyer CEOs are associated with a lower future volatility of both earnings and returns. Using a market-based measure of information asymmetry, we find that CEO legal expertise increases information transparency. We also find that firms led by lawyer CEOs, on average, pay about 5% lower audit fees than those headed by nonlawyers, which is in line with both decreased business risk and better financial reporting in such firms.

Since the effects of corporate governance on credit risk are usually more pronounced for riskier, more vulnerable firms, we test the hypothesis that CEO legal expertise has a stronger effect on such firms. We test the impact of lawyer CEOs on corporate credit ratings separately for a) firms facing relatively high and low levels of financial constraints, b) firms facing relatively high and low levels of market competition, and c) firms with higher and lower levels of past variability. We find that the CEO’s legal background has a stronger effect on the credit ratings of firms that are riskier or operate in more uncertain economic environments.

Our paper contributes to the literature in two ways. First, it contributes to a growing literature that aims to understand the implications of managerial background, behavior, and experiences on corporate policies and outcomes. We contribute to this line of research by showing that executives’ legal expertise influences their firms’ default risk and cost of debt. We also find that CEO legal training affects how auditors price of their services. Second, this study contributes to the literature investigating the determinants of credit rating assessments. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to examine the effect of lawyer CEOs on credit risk assessments. We find that CEO legal expertise is an important credit risk factor incremental to firm fundamentals. To that extent, our paper aligns with those of Kuang and Qin (2013), Bonsall IV et al. (2017), Cornaggia et al. (2017), and Bernile et al. (2017), who show that CEOs’ personal traits should be considered when assessing their firms’ default risk. We also find that CEO legal training matters to pricing in debt markets, with firms headed by lawyers associated with narrower offering credit spreads.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 discusses our main hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data collection and our sample. Section 4 discusses our main regression findings. Sections 5 discusses the channels through which the effect of lawyer CEOs on credit ratings is likely. Section 6 provides robustness checks. Section 7 concludes.

2 Hypothesis development

Our focus is on the association between CEO legal education and a firm’s credit ratings. We expect lawyer CEOs to contribute to better credit ratings for three reasons. First, credit rating agencies are likely sensitive to any changes in a firm’s internal monitoring and gatekeeping functions (Ham and Koharki 2016).Footnote 4 A considerable proportion of lawyers serve as executives of corporations (40% of executives), and executive lawyers are often endowed with gatekeeping responsibilities (Morse et al. 2016).Footnote 5 Second, firms headed by lawyers tend to pursue conservative investment policies (Henderson et al. 2018) that can reduce the volatility of future cash flows and the likelihood of their companies missing principal and interest payments. Correspondingly, the reduction in firm risk should enhance the firm’s overall creditworthiness. Third, executives with legal expertise are less likely to exploit private information for personal gain (Jiang et al. 2021) and help enhance corporate disclosure transparency (Pham 2020). Given that an enhanced information environment reduces default risks (Francis et al. 2005; Cheng and Subramanyam 2008; Brogaard et al. 2017), firms led by lawyer CEOs can be associated with lower default risk and hence exhibit more favorable credit ratings.Footnote 6 Our first hypothesis therefore is as follows.

-

H1: The debt securities of firms led by lawyer CEOs have higher credit ratings.

Since we expect the effect of lawyer CEOs on credit ratings to be driven by the overall lowering of firm credit risk, we expect that the market-based assessment of credit risk will be lower for such companies. This motivates our second hypothesis, as follows.

-

H2: The cost of debt is lower for firms led by lawyer CEOs.

Finally, the effects of corporate governance and other factors on credit risk tend to be highly nonlinear, with the riskiest firms being the most sensitive to managerial actions and incentives (e.g., Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006; Cheng and Subramanyam 2008; Kabir et al. 2013). If lawyer CEOs do affect credit risk, we expect this effect to be particularly pronounced for those firms most affected by financial uncertainty. This leads to our third hypothesis, as follows.

-

H3: The positive effects of lawyer CEOs on their firms’ credit ratings are more pronounced for riskier firms.

3 Data and variables

3.1 Data and sample

We obtain information on stock prices, stock returns, and trading volumes from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP). Compustat is our source for firm-specific accounting data and credit ratings. We obtain data for the number of analysts following a firm from the Institutional Brokers’ Estimate System (I/B/E/S) database, and institutional ownership data from the Thomson Reuters Institutional Holdings (13F) Database. We collect additional data on managerial compensation from ExecuComp, personal characteristics and educational background of the executives from Marquis Who’s Who and BoardEx, and data on boards of directors from the Institutional Shareholder Services database. We source corporate social rating data from the Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Research & Analytics (KLD) database. We obtain corporate bond data from the Mergent Fixed Income Securities Database (FISD). We obtain the credit default swap (CDS) spread data from the Markit database. We source audit fee data and other standard control variables from the Audit Analytics database. To mitigate the effects of outliers, we winsorize all continuous variables at the first and 99th percentiles. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Cheng and Subramanyam 2008), we exclude from our sample financial and utility firms. Our final sample consists of 10,655 firm-year observations spanning 1992–2020. We provide a detailed description of the variables in Appendix Table 11.

3.2 Credit rating measures

We obtain S&P’s Long-Term Domestic Issuer Credit Rating data from Compustat/Capital IQ database. Following the literature on credit risk assessment (e.g., Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2013; Kuang and Qin 2013; Bonsall IV et al. 2017; Cornaggia et al. 2017), we construct numeric variables reflecting the ratings of the issuers in our sample. Specifically, we translate ratings numerically, increasing in credit quality as follows: D (or SD) = 1, …, AAA = 22. Appendix Table 12 provides the details for the credit rating classification. As the credit ratings are provided monthly by Compustat/Capital IQ database, we follow Ham and Koharki (2016) and use the average of a firm’s monthly credit rating in a given fiscal year (denoted RATING) as our main measure of credit risk.

We also employ two alternative measures of credit risk as suggested by the literature. First, we use credit ratings from Egan-Jones Ratings Company, an investor-pays rating agency (e.g., Bonsall IV et al. 2017). Second, we obtain the CDS spread from the Markit database as an alternative credit market risk measure (e.g., Zhang et al. 2009; Ham and Koharki 2016).

3.3 Lawyer CEO measure

We hand-collect from Marquis Who’s Who and BoardEx, two of the most comprehensive databases for CEOs’ personal biographical details, information on the personal characteristics and educational background of the executives in our sample. Specifically, we identify CEOs by name using ExecuComp’s classification (data item CEOANN = CEO). We classify a manager as a lawyer CEO, where LAWYER_CEO = 1, if the CEO has a law degree (LLB, BCL, LLM, LLD, or JD) or a doctorate in jurisprudence.

To control for other known CEO characteristics, we hand-collect information on the CEOs’ country of birth, education, and other personal biographical details from Marquis Who’s Who, BoardEx, and several other databases, including the Notable Names Database (nndb.com), Reference for Business, Bloomberg.com, Wikipedia, and, in the last instance, Google searches, to cross-check the information obtained from Marquis Who’s Who. This allows us to compile a comprehensive dataset of several CEO attributes. Finally, we compute CEO risk incentives from compensation contract data following the methodology of Core and Guay (2002).

3.4 Descriptive statistics

We present the descriptive statistics for our variables in Panel A of Table 1. For each variable, we provide information about the total number of observations, the mean and median values, the standard deviation, and the values at the 25th and 75th percentiles.

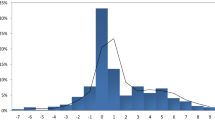

We find that firms headed by CEOs with legal degrees account for 9.2% of the total number of companies in our sample. The average firm has a logarithm of firm size (LNSIZE) of 8.32 and finances 29.9% of its book debt. The average firm earns a 4.30% return on assets (ROA) and covers its interest 14.67 times; 16.2% of firm-year observations have negative earnings, and the average natural logarithm of the number of analysts issuing an annual forecast (LNANALYST) is 2.45. Regarding credit rating measures, the average rating (RATING) is 13.066, with a median of 13, corresponding to a medium rating (BBB-). The average rating from Egan-Jones Ratings Company is 14.74, and the average CDS spread is 157.58 bps. Overall our credit rating and firm characteristics are in line with prior studies (e.g., Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006; Cheng and Subramanyam 2008; Zhang et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2013; Kuang and Qin 2013; Bonsall IV et al. 2017; Cornaggia et al. 2017; Pham 2020).

4 Main results

4.1 Lawyer CEOs and credit ratings

In this section, we examine whether and to what extent the legal expertise of CEOs affects the assessment of credit risk. We use the following regression.

where, for firm i and time t, RATING is the S&P issuer credit rating; LAWYER_CEO is an indicator variable that takes the value of one if the CEO has a law degree and zero otherwise; FIRMCTRL refers to firm-level control variables; CEOCTRL refers to CEO characteristic variables; and FE refers to firm and year fixed effects. We lag all independent variables by one year, relative to the credit rating measures, to avoid potential reverse causality issues (Pham 2020; Kempf and Tsoutsoura 2021). The timing of the variables is described in Fig. 1.

Timeline of the variables. This figure presents an example of the timeline of the estimation of the variables. The credit rating for Year t (in this example, 2010) is measured as the average monthly credit rating over that year (from the end of January to the end of December). The Lawyer CEO dummy is estimated on December 31 of Year t-1 (2009 in this example). The control variables are also measured on December 31 of Year t-1

Regarding control variables, we control for various firm characteristics that can be associated with firm credit risk assessment, as suggested by the literature. Specifically, we include firm size (LNSIZE), since larger firms tend to face lower risk and thus have higher credit ratings (e.g., Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006; Bonsall IV et al. 2017). Following prior studies (e.g., Kaplan and Urwitz 1979; Ziebart and Reiter 1992; Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006; Bonsall IV et al. 2017; Cornaggia et al. 2017), to proxy for a firm’s default risk, we use the debt-to-asset ratio (LEVERAGE), the return on assets (ROA), interest coverage (INT_COV), and an indicator of whether the firm reported negative earnings in the prior fiscal year (LOSS). Following Hutton et al. (2009) and Kim and Zhang (2016), we measure accrual quality (ACCRUAL) by estimating the three-year moving sum of absolute discretionary accruals, where discretionary accruals are estimated with the modified Jones (1991) model, following Dechow et al. (1995). We control for differences in firms’ asset structure (CAP_INTEN), since firms with greater capital intensity tend to be less risky for creditors and are thus expected to have better credit ratings. We account for differences in firms’ debt structure by including an indicator variable, SUBORD, that equals one if the firm has subordinated debt and zero otherwise (e.g., Kaplan and Urwitz 1979; Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006). We further control for the market-to-book ratio (LNMTB), the volatility of a firm’s operating cash flow (STDCFO), and the volatility of a firm’s stock return (RETVOL) to capture expected growth prospects and risk factors reflected in equity returns (e.g., Sloan 1996; Bhojraj and Sengupta 2003; Francis et al. 2005; Cheng and Subramanyam 2008; Cornaggia et al. 2017; Correia et al. 2018). We also include the number of analysts following a firm (LNANALYST), since Cheng and Subramanyam (2008) find that this is negatively associated with its default risk and thus positively related to credit ratings.

We account for other CEO characteristics and management attributes that can be associated with credit risk assessments. Specifically, we control for the risk-taking incentives of CEOs, since Kuang and Qin (2013) find they matter in credit risk assessments. Following the literature (e.g., Core and Guay 2002; Coles et al. 2006), we employ the sensitivity of managerial wealth to stock prices (LNDELTA) and to the volatility of a firm’s stock returns (LNVEGA), where LNDELTA and LNDELTA are measured as the natural logarithm of one plus the dollar change in wealth associated with a 1% change in the firm’s stock price (the standard deviation of the firm’s returns). We control for high-ability management, since Bonsall IV et al. (2017) and Cornaggia et al. (2017) find it relates to a firm’s risk profile. We adopt the managerial ability score proposed by Demerjian et al. (2012) and use an indicator indicating capable managers if the score is above the sample median.

We control for high-ability CEOs using four indicators that capture their educational background: MBA, PHD, IVY_EDUC, and FINTECH_EDUC. We also account for the top five highest-paid general counsels, since Ham and Koharki (2016) find that credit risk increases following a general counsel’s promotion to senior management. We control for corporate general counsel to ensure that CEO legal expertise directly influences credit ratings, independent of the effect of general counsel. Following Kwak et al. (2012), Hopkins et al. (2015), and Ham and Koharki (2016), we use the annual title from the ExecuComp database to construct our general counsel measure. Specifically, to identify executives who are general counsels, we search the annual titles of executive-firm-years for terms containing counsel, law, legal, and similar variants.Footnote 7 We manually search the executives’ titles and exclude titles that do not refer to legal expertise, such as tax counsel and investment counsel. Our measure of corporate counsel, HIGHPAID_GC, is a dummy variable that takes the value of one if a firm has corporate counsel among the top five highest-paid executives and zero otherwise.

Finally, we control for year and firm fixed effects to control for time- and firm-invariant factors, respectively, that could be associated with credit ratings. We employ robust standard errors clustered by both firm and year dimensions to account for dependence both across firm and time (Cameron et al. 2011; Petersen 2009; Thompson 2011). We present the baseline regression results in Table 2.

We present five regression specifications: a model without any firm-specific control variables, two models with firm-specific control variables that relate to credit risk assessment, and two models with additional controls for other CEO characteristics and management attributes.Footnote 8 We find that the LAWYER_CEO variable is positively and significantly related to the measure of credit rating. The results hold for different model specifications. These findings suggest that firms headed by lawyer CEOs have better credit ratings.

Regarding control variables, we observe that credit risk assessments are more favorable for firms with the following attributes: larger size, a higher return-to-assets ratio, greater capital intensity, higher expected growth prospects as measured by the market-to-book ratio, and higher analyst following. Credit ratings are lower for firms with greater leverage, a loss in the prior fiscal year, subordinated debt, and greater stock return volatility. Consistent with Bonsall IV et al. (2017) and Cornaggia et al. (2017), we find that firms led by more capable managers are associated with higher credit ratings. We also find that firms with high-paid general counsel are associated with higher credit risks, in alignment with Ham and Koharki (2016).Footnote 9 Overall, the results for the control variables are consistent with studies on the determinants of credit risk assessment (e.g., Kaplan and Urwitz 1979; Bhojraj and Sengupta 2003; Francis et al. 2005; Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006; Cheng and Subramanyam 2008; Bonsall IV et al. 2017; Cornaggia et al. 2017).

4.2 CEO turnover test

We acknowledge that the documented relation between CEO legal training and firms’ credit risk could suffer from an omitted correlated variable bias. For example, firms could endogenously appoint lawyer CEOs based on certain firm characteristics and, at the same time, these characteristics could influence a firm’s credit risk assessment. To mitigate concerns that omitted firm or performance characteristics drive our results, we implement an identification strategy based on CEO turnover. We examine whether CEO turnover is associated with changes in firm credit ratings by tracing cases of CEO turnover in which we can identify a change in legal education between the new and old CEOs. Specifically, we study a sample of CEO changes with necessary credit rating and control variables during our sample period. Our sample for this test consists of 742 CEO changes, including 119 cases from nonlawyer CEOs to lawyer CEOs and from lawyer CEOs to nonlawyer CEOs. We follow Bonsall IV et al. (2017) and Kuang and Qin (2013) to analyze these changes. Specifically, we first transform our baseline model (Eq. (1)) into the first difference. This approach should remove time-invariant firm effects. We then replace LAWYER_CEO with ΔLAWYER_CEO, which equals one for a change from a nonlawyer to a lawyer CEO, minus one for a change from a lawyer to a nonlawyer CEO, and zero if the CEO legal background did not change.

The variable ΔCreditRating is the change in the S&P credit rating measures from Compustat in the following way. We manually collect the CEO announcement date from Factiva (an online database of business news produced by Dow Jones and Reuters) and the SEC’s EDGAR database. The dependent variable of interest is the change in the S&P credit ratings six months before to six months after the CEO announcement date. Figure 2 describes the timeline of the measurement of credit rating changes and other variables surrounding the CEO announcement dates.

Timeline of the credit rating changes surrounding the CEO announcement dates. This figure presents an example of the timeline of the credit rating changes surrounding the CEO change announcement date. In our example, the announcement of the CEO change occurs on October 1, 2010. The Lawyer CEO dummy is measured before and after the announcement. The control variables are measured at the end of the fiscal year prior to the CEO change on December 31, 2009, and after the CEO change on December 31, 2010. The credit rating before the change is measured in April 2010 (six months before the CEO change announcement). The post-change credit rating is measured in March 2011 (six months after the CEO change announcement). The change in credit ratings is measured as the difference between post- and pre-announcement credit ratings

We report the results for the CEO change test in Table 3.

Despite the small sample size, we find that changes in CEO legal background caused by a CEO turnover are positively and significantly associated with changes in firms’ credit ratings.Footnote 10 The results in Table 3 therefore provide additional support for our prediction that lawyer CEOs contribute to improvements in credit risk assessments.

Figure 3 presents the evolution of credit ratings surrounding CEO changes.Footnote 11 The orange line presents the average of credit ratings when there is a change from nonlawyer CEO to lawyer CEO. The blue line presents the average of credit ratings when there is a change from a lawyer CEO to a nonlawyer CEO. The gray line presents the average of credit ratings surround other CEO changes. Credit ratings are detrended and month t – 6, compared to the CEO change month, is normalized to zero. Overall Fig. 3 suggests that the appointment of a CEO with legal training enhances a firm’s credit rating, whereas there is no clear pattern in credit ratings when a lawyer CEO is replaced by a nonlawyer CEO or when other CEO changes occur.

Credit ratings around CEO changes. This figure presents the credit rating surrounding CEO changes. The orange line presents the average of credit ratings when there is a change from nonlawyer CEO to lawyer CEO. The blue line presents the average of credit ratings when there is a change from lawyer CEO to nonlawyer CEO. The gray line presents the average of credit ratings surround other CEO changes. Credit ratings are detrended using the time trend from the “Other changes” category, and month t – 6, compared to the CEO change month, is normalized to zero

4.3 Credit risk versus economic bonding

Our analysis so far suggests that sophisticated market participants, such as credit rating agencies, incorporate CEO legal expertise into their credit rating assessments. It is important to distinguish two possible reasons for this result: does the market believe that the credit risk of such firms is lower, or do lawyer CEOs influence firms’ ratings without affecting their credit risk? In this section, we test these alternative explanations of our results.

4.3.1 Lawyer CEOs and the cost of debt capital

Arguably, one of the best market-based measures of a company’s credit risk is the cost of its debt. In this section, we study whether and to what extent lawyer CEOs impact bond investors’ required rates of return. Our analysis of the effect of CEO legal expertise on the cost of debt capital serves two purposes. First, we examine whether managers with legal expertise can reduce their firms’ cost of debt capital. Second, we study whether CEO legal expertise explains variations in credit spreads incremental to issuance-specific characteristics, such as credit ratings. This evidence provides more insight into how bond prices capture executives’ legal expertise.

We consider all new issue nonconvertible fixed-rate corporate bonds issued between 1992 and 2020 reported by the Mergent FISD. We then match the FISD data with the Compustat, CRSP, ExecuComp, BoardEx, and Thomson Reuters data, obtaining a final sample of 3223 bond issuances during our sample period. We measure offering credit spreads as the offering yields to maturity in excess of similar duration treasuries and use the following regression.

where SPREAD is the offering credit spread; LAWYER_CEO is an indicator variable that takes the value of one if the CEO has a law degree and zero otherwise; ISSUECRTL refers to issuance-specific characteristics; FIRMCTRL refers to firm-level control variables; CEOCTRL refers to CEO characteristic variables; and FIRM FEs (YEAR FEs) refer to firm (year) fixed effects.

We control for issuance characteristics, including bond-specific S&P ratings (BOND_RATING), the offering amount of the new bond (ISSUE), the number of months until the maturity of the new bond (MATURITY), an indicator of whether the new bond-related debt is senior for issuance (SENIOR), and an indicator of whether the new bond has credit enhancements (ENHANCE). We further control for various firm characteristics associated with credit quality, as in the baseline regression (column (4) of Table 2). Finally, we control for year and firm fixed effects to control for time- and firm-invariant factors, respectively, that could be associated with credit spreads. We present the results for this test in Table 4.

We present three regression specifications: 1) a model without issuance and firm control variables, 2) a model with all issuance and firm control variables, and 3) a model with all issuance attributes, firm control variables, and other management attributes, as in the baseline model in Table 2. In Models (1) and (2), the LAWYER_CEO variable relates negatively and significantly to the measure of credit spread, suggesting that CEO legal expertise is associated with a lower credit spread. The results reported in Models (2) and (3) suggest that there could be ways that CEO legal training affects bond costs. Specifically, the estimated coefficients on LAWYER_CEO are negative and statistically significant between the different model specifications, which is consistent with CEO legal training affecting credit spreads directly. Moreover, the coefficients on BOND_RATING are also negative and statistically significant, suggesting that CEO legal expertise affects credit spreads indirectly through its impact on credit ratings. The magnitude of the effect of CEO legal expertise on credit spreads is also economically significant, with firms led by lawyer CEOs having, on average, about 10% (about 19 bps) lower costs than firms headed by nonlawyer CEOs.Footnote 12 Taken together, the results of Table 4 suggest that CEO legal expertise impacts bond pricing through direct and indirect channels, confirming H2.Footnote 13

4.3.2 Testing for economic bonding

In this section, we attempt to address the concern that lawyer CEOs can influence issuer-pay rating agencies, which could lead to an increase in the ratings (i.e., the economic bonding hypothesis). Although these potential bonding relationships are unobservable and hence cannot be ruled out, we provide several tests to mitigate this concern.

First, we examine the possibility that the credit rating agencies themselves could have incentives to bond with the CEOs, since the bond issuers pay the rating agencies directly for their services. We address this concern by conducting a test using ratings from Egan-Jones Ratings Company, an investor-pays rating agency whose fees are not paid by insurers.Footnote 14 We report the results for this test in columns (1) to (3) in Table 5.

We present three regression specifications: a model without any control variables, a model with firm-specific control variables, and a model with all the firm-specific variables and other management attributes, as in the baseline model in Table 2. Across different model specifications, we consistently find that the relation between lawyer CEOs and credit ratings is positive and statistically significant for non-issuer-paid ratings. This result confirms that our main findings are not driven by issuer-pay incentives.

Second, firm managers could have incentives for economic bonding when their firms have rating-based performance pricing provisions in their private lending contracts. To address this concern, we examine whether the relation between lawyer CEOs and credit ratings is only found among firms with rating-based performance pricing provisions in their private lending contracts, as obtained from the DealScan database. Specifically, we re-estimate our baseline model (Table 2, Model (4)) for two subsamples of firms, with and without the performance pricing information. We report the results for these tests in columns (4) and (5), respectively, in Table 5. We find that the effect of lawyer CEOs on credit ratings is not limited to firms with rating-based performance pricing provisions. Using SUR and the Wald test for the coefficient differences between the two subsamples, we find no significant difference in the magnitudes of the association between CEO legal expertise and credit rating in these two subsamples.

Overall the results in Table 5 suggest that i) the relation between lawyer CEOs and credit ratings is positive and statistically significant for the non-issuer-paid ratings, and ii) the results are not concentrated among firms with rating-based performance pricing provisions in their loan contracts. The findings in the table therefore consistently suggest that economic bonding is not likely to be an omitted variable in our model of lawyer CEOs and credit ratings.

5 Path analyses

In this section, we discuss two possible mechanisms through which lawyer CEOs affect their firms’ credit risk assessment: reduction in future risk and improvement in information asymmetry. We follow the literature (e.g., DeFond et al. 2016; Landsman et al. 2012; Lang et al. 2012) and conduct path analyses to investigate whether there is a direct link in which the reduction in future risk and improvement in information asymmetry can serve as mediator variables influenced by lawyer CEOs that, in turn, influence their firms’ credit risk assessment.Footnote 15

Figure 4 and Table 6 present a path analysis that examines the effect of lawyer CEOs on credit ratings through ex ante future volatility and information risk. We estimate the following models in the path analyses.

Path analysis. This figure depicts the direct and indirect paths through which lawyer CEOs can affect credit ratings. We estimate the following models in the path analysis. Ratingt = β0 + β1∗Lawyer CEOt − 1 + β2∗ Volatilityt + β3∗Information Riskt + Controls + ℇt. (a), Volatilityt = α0 + α1∗ Lawyer CEOt − 1 + Volatilityt − 1 + Controls + ℇt. (b), Information Riskt = μ0 + μ1∗ Lawyer CEOt − 1 + Information Riskt − 1 + Controls + ℇt. (c). The independent variable of interest is an indicator denoting if a firm is led by a lawyer CEO. Rating refers to credit rating measure, as discussed in Model (1). Return Volatility is measured by the annualized stock return volatility based on the standard deviation of the daily stock returns over a fiscal year. To capture Information Risk, we use the logarithm of Corwin and Schultz’s (2012) bid-ask spread measure. The term Controls represents the relevant control variables from the baseline regression in Model (1). Firm and year fixed effects are included in all the models. The path coefficient β1 is the magnitude of the direct path from lawyer CEOs to credit ratings. The path coefficient β2 (β3) is the magnitude of the path from future volatility (information risk) to credit ratings. The path coefficient \( {\hat{\upalpha}}_1\times \hat{\beta_2}\ \Big({\hat{\upmu}}_1\times \hat{\beta_3} \)) is the magnitude of the indirect path from lawyer CEOs to credit ratings mediated through future volatility (information risk). The significance of the indirect effect is estimated using Sobel (1982) test statistics. The table reports the path coefficients of interest. *, **, and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

The independent variable of interest is an indicator equal to one if a firm is led by a lawyer CEO. Rating refers to the credit rating measure as discussed in Model (1). Return Volatility, measured by the annualized stock return volatility, is based on the standard deviation of the daily stock returns over a fiscal year (Bonsall IV et al. 2017; Brogaard et al. 2017; Correia et al. 2018). To capture Information Risk, we use bid-ask spread as a measure of information asymmetry (Diamond and Verrecchia 1991; Bartov and Bodnar 1996; Leuz and Verrecchia 2000; Frankel and Li 2004). Specifically, we follow Corwin and Schultz (2012) and estimate a bid-ask spread estimator from daily high and low prices. We compute the annual spread for each stock based on the average daily spread over a year. As information asymmetry can vary across industries (Pham 2020), we construct an industry-adjusted spread measure, defined as the difference between each firm’s bid-ask spread and the industry average value, scaled by industry standard deviation. The higher the spread, the greater the information asymmetry. The controls are the relevant control variables from the baseline regression in Model (1). We also include the lagged values of return volatility and information risk measures in equations (b) and (c), respectively. The path coefficient β1 is the magnitude of the direct path from lawyer CEOs to credit ratings. The path coefficient β2 (β3) is the magnitude of the path from future volatility (information risk) to credit ratings. The path coefficient \( {\hat{\upalpha}}_1\times \hat{\beta_2}\ \Big({\hat{\upmu}}_1\times \hat{\beta_3} \)) is the magnitude of the indirect path from lawyer CEOs to credit ratings mediated through future volatility (information risk). The significance of the indirect effect is estimated using Sobel (1982) test statistics.

The results of Table 6 suggest that return volatility reduction is a significant channel that helps explain 10.23% of the positive relation between lawyer CEOs and credit ratings.

Similarly, information risk is another significant channel that helps explain 2.77% of the positive relation between lawyer CEOs and credit ratings. These findings are consistent with the literature suggesting that rating agencies account for the variability of a firm’s future performance in their credit risk assessment (e.g., Kaplan and Urwitz 1979; Blume et al. 1998) and that a transparent information environment implies a reduction in default risk and correspondingly more favorable credit ratings (Francis et al. 2005; Cheng and Subramanyam 2008; Brogaard et al. 2017). Overall, the path analysis in Table 6 suggests that the effects of lawyer CEOs and credit ratings are mediated through at least two channels: i) information risk and ii) future volatility.Footnote 16

6 Other tests

6.1 Cross-sectional analysis

Hypothesis 3 states that the positive impact of CEO legal expertise is particularly pronounced for riskier firms. To test this hypothesis, we estimate the effect of lawyer CEOs on corporate credit ratings separately for 1) firms facing relatively high and low levels of financial constraints, 2) firms facing relatively high and low levels of market competition, and 3) firms with higher and lower levels of past variability and test for differences between these groups.

First, we use the Kaplan and Zingales (1997) index, as reported by Lamont et al. (2001) as a proxy for financial constraints and estimate our baseline regression (Eq. (1)) separately for groups with high and low levels of financial constraints. For each year, we sort firms into terciles based on the value of each measure and define high (low) levels of the measure based on the top (bottom) tercile of the measure. Consistent with previous sections, in all regressions, we control for year and firm fixed effects to control for time- and firm-invariant factors, respectively, that could be associated with credit risk assessment. We report the results for this test in columns (1) and (2), respectively, of Table 7.

Comparing the two subsamples, we observe that the coefficient on LAWYER_CEO is significantly positive in the group with high financial constraints and statistically insignificant in the low-constraints group. A test for coefficient differences across the high- and low-constraints subsamples indicates that the coefficient on LAWYER_CEO is statistically larger for the high-constraints subsample. These results suggest that CEO legal expertise is a significant credit rating factor, independent of its impact on prior firm performance and other observable characteristics (e.g., size, capital intensity, and capital structure) but only for firms with a high probability of financial constraints.

Second, we test the relevance of lawyer CEOs for corporate credit ratings separately for firms facing high and low product market threats, where we employ the firm-level product market threats developed by Hoberg et al. (2014). As levels of competition can vary across industries (Hoberg and Phillips 2010), we construct an industry-adjusted competition measure, defined as the difference between each firm’s product market threats and the industry average value, scaled by industry standard deviation. We then rerun the baseline regression (Eq. (1)) for the two groups of firms based on their measure of market threats and observe that the coefficient on LAWYER_CEO is significant in the high-competition subsample. A test for differences in the coefficients between the high- and low-market competition subsamples suggests that the coefficient on LAWYER_CEO is statistically larger for the high-competition subsample compared with the low-competition subsample. The results of columns (3) and (4) suggest that CEO legal training is a more important credit rating factor (independent of its impact on firm characteristics) for firms facing higher levels of market competition.

Finally, we examine whether the impact of CEO legal expertise on credit risk assessment is more pronounced among firms that operate in a highly uncertain environment. We conjecture that legal training that helps CEOs with risk management is likely to have a stronger impact on credit quality under riskier circumstances. To test this possibility, we run the baseline regression (Eq. (1)) separately for two subsamples of firms based on the standard deviation of monthly stock returns during the previous fiscal year. For each year, we sort firms into terciles based on the value of each measure and define high (low) levels of the measure based on the top (bottom) tercile of the measure. We report the results for this test in columns (5) and (6). We observe that the coefficient on LAWYER_CEO is significant in both subsamples of firms. We test the coefficient differences between the high- and low-variability subsamples and find that the coefficient for the high-variability subsample is statistically larger than that in the low-variability subsample. Collectively, the results of columns (5) and (6) support our prediction that CEO legal expertise impacts credit risk assessment to a greater extent when firms operate in a highly uncertain environment, confirming H3.

6.2 Sensitivity and additional analyses

We supplement the baseline regression results in Table 2 with a number of robustness tests to ensure that our results are insensitive to specific model specifications, sample selection, or alternative measures of corporate default risk.

6.2.1 Lawyer CEOs and CDS spreads

In this subsection, we consider CDS spread an alternative measure of credit market risk. We obtain the CDS spread data from the Markit database and follow Micu et al. (2006) and Zhang et al. (2009) and use five-year CDS spreads, because these contracts are the most liquid and provide the most reasonable pricing estimate of the underlying asset’s default risk (Ham and Koharki 2016). We present the results for this analysis in Table 8.

Consistent with prior analysis, we present four regression specifications: a model without firm-specific control variables, a model with firm-specific control variables, and two models with all the firm-specific control variables and other management attributes, as in the baseline model in Table 2. In the full model, after controlling for all available firm and CEO characteristics as well as fixed effects, we find that having a lawyer CEO is associated with a 17-bp lower CDS spread.Footnote 17 The results in Table 8 suggest that firms led by lawyer CEOs are associated with lower credit default spreads, consistently suggesting the role of lawyer CEOs in reducing firms’ credit risks.

Figure 5 presents the CDS spreads surrounding CEO changes.Footnote 18 The orange line presents the average of CDS spreads when there is a change from lawyer CEO to nonlawyer CEO. The blue line presents the average of CDS spreads when there is a change from nonlawyer CEO to lawyer CEO. The gray line presents the average of CDS spreads surrounding other CEO changes. Overall Fig. 5 suggests that the firm’s credit risk declines, as evidenced by a reduction in CDS spread, following the appointment of a lawyer CEO, whereas the firm’s CDS spread increases when a lawyer CEO is replaced by a nonlawyer CEO.

CDS spread around CEO changes. This figure presents the CDS spread surrounding CEO changes. The orange line presents the average of CDS spreads when there is a change from lawyer CEO to nonlawyer CEO. The blue line presents the average of CDS spreads when there is a change from nonlawyer CEO to lawyer CEO. The gray line presents the average of CDS spreads surrounding other CEO changes

6.2.2 Sensitivity analysis

So far, we have focused on credit ratings to measure corporate default risk, since they reflect a firm’s overall creditworthiness (S&P 2002). In Model (1) of Table 9, we consider an alternative measure of corporate default risk. Specifically, we use Merton’s (1974) distance-to-default measure (DTD), as applied by Bharath and Shumway (2008). We follow Bharath and Shumway (2008) and Brogaard et al. (2017) and compute the DTD as follows.

where Equityi, t is the market value of equity, measured as the product of the number of shares outstanding and the stock price at the end of the year; Debti, t is the face value of debt, measured as the sum of debt in current liabilities and one-half the long-term debt at the end of the year; ri, t − 1 is firm i’s past annual return; σEi, t is the stock return volatility for firm i during year t, estimated using the monthly stock return from the previous year; σVi, t is an approximation of the volatility of firm assets; and Ti, tis set to one year. A high (low) DTD value indicates relatively low (high) default risk.

In Model (2) of Table 9, we examine the relation between CEO legal expertise and credit risk assessment using ordered probit models (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006; Cheng and Subramanyam 2008). As Bernile et al. (2017) note, the ordinary least squares estimation is less sensitive to a large number of fixed effects in the model but requires that the distance between two adjacent rating categories be constant across the full range of ratings. The ordered probit estimation, on the other hand, can accommodate the varying distances between adjacent rating categories but is more sensitive to a large number of fixed effects. We therefore report the results from the ordered probit model in Model (2) to complement the ordinary least squares results.

In Model (3) of Table 9, we test the robustness of our baseline results to alternative standard errors two-way clustered by year and CEO, following Kuang and Qin (2013) and Cornaggia et al. (2017).Footnote 19 All of the tests in Models (1) to (3) support our main results and indicate a significant negative association between lawyer CEOs and their firms’ credit risk.

Next we run the baseline model (Eq. (1)) after including additional control variables. We control for earnings quality, since it can be associated with a firm’s cost of capital and credit rating (e.g., Francis et al. 2005; Francis et al. 2008; Armstrong et al. 2010; Alissa et al. 2013). We follow Barth et al. (2013) and construct earnings transparency measures. We measure earnings transparency using a two-step estimation procedure to allow for intertemporal and cross-sectional variations in our measure.Footnote 20

In addition, we control for rollover risk, since Gopalan et al. (2014) suggest that firms with greater exposure to rollover risk exhibit lower credit quality. We follow these authors and measure a firm’s exposure to rollover risk using the variable LTt-1, which is defined as the amount of the firm’s long-term debt outstanding at the end of year t - 1 due for repayment in year t, scaled by its book value of total assets at the end of year t - 1. We focus on ΔLTt-1, which equals LTt-1 - LTt-2, since a larger value of ΔLTt-1 denotes a greater increase in the firm’s exposure to rollover risk.

We further control for CSR, since a firm’s CSR performance impacts the pricing of corporate debt and the assessment of credit quality (Oikonomou et al. 2014; Ge and Liu 2015). We therefore control for CSR to ensure that the effect of CEO legal training on credit risk assessment is not driven by CSR performance. We source corporate social rating data from the KLD database and follow Cronqvist and Yu (2017) to construct a CSR score. Specifically, KLD rates companies by using six CSR categories (i.e., community, diversity, employee relations, the environment, human rights, and product) and provides a number of strengths and concerns for each category. For each firm-year, each strength adds +1 to the score, and each concern adds −1. We aggregate the scores for each category and then aggregate them across all six categories. The CSR score equals the number of strengths minus the number of concerns. We follow Cronqvist and Yu (2017) and normalize these scores so that the minimum is zero, for straightforward interpretation. A higher score indicates a more socially responsible rating.

Furthermore, we consider whether corporate governance can explain the effect of CEO legal expertise on a firm’s credit risk. The importance of corporate governance for the corporate information environment and risk taking has been extensively documented.Footnote 21 In the context of credit risk assessment, Klock et al. (2005) find firms with strong antitakeover provisions are associated with a lower cost of debt financing, while Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. (2006) show that firms with better governance have more favorable credit ratings. A potential concern is that the documented effect of lawyer CEOs on credit ratings could be driven by the strength of the firm’s governance. We examine this possibility by controlling for a comprehensive set of governance proxies, including a) the corporate governance index constructed by Gompers et al. (2003), based on 24 governance provisions; b) institutional ownership (Bhojraj and Sengupta 2003); c) a takeover index constructed from laws (Cain et al. 2017), and d) three measures of board quality, that is, board size, the share of independent directors on the board (Dahya et al. 2008; Hazarika et al. 2012), and co-opted boards (Coles et al. 2014).Footnote 22 We construct these governance measures using the RiskMetrics database.

In Model (4) of Table 9, we re-estimate our baseline model after including the nine additional control variables mentioned. Although the sample shrinks significantly (from 10,655 to 2304 firm-year observations), the coefficient of LAWYER_CEO remains positive and statistically significant, consistently indicating that the effect of CEO legal expertise on credit risk is not confounded by any (or all) of the above firm characteristics and alternative explanations.

In Model (5) of Table 9, we examine whether the legal training of CFOs affects the effect of CEO legal expertise on a firm’s credit risk. It could be argued that CEOs make strategic decisions while CFOs make the financing decisions and that the CFO’s legal training should matter more than that of the CEO. On the other hand, Malmendier et al. (2011) posit that, although CFOs design the financing decisions, the CEO has the final say. Nevertheless, we manually collect CFOs’ educations and conduct further tests to ensure our results are not explained by CFOs’ legal education. The results of Model (5) suggest that lawyer CEOs still significantly influence credit ratings, even after we control for CFO legal training.

In Models (6) and (7) of Table 9, we consider alternative sampling methods. Specifically, to rule out the possibility of the documented effect of CEO legal expertise on credit risk being driven by the global financial crisis (2007–2009), we rerun our baseline models after excluding this crisis and report the results in Model (6). Dimitrov et al. (2015) investigate the impact of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) on corporate bond ratings by credit rating agencies and document that, following the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, the agencies issued lower ratings and issued downgrades with less information. We therefore rerun our baseline models after excluding the period after the implementation of the Dodd-Frank Act to ensure the act cannot explain our documented effect. We report the results for this test in Model (7).

Overall the results from the robustness tests in Table 9 suggest that the effect of CEO legal expertise on corporate credit ratings is robust across various model specifications, sampling methods, and alternative measures of default risk or alternative explanations.

6.3 Lawyer CEOs and audit pricing

Our analysis so far suggests that, when assessing a firm’s credit risk, debt market participants consider CEO legal expertise, which helps CEOs facilitate corporate transparency and risk management. In this section, we further examine whether other firm stakeholders value CEO legal expertise. We focus on auditors for two reasons. First, auditors are important participants in financial markets and are particularly sensitive to the credibility of corporate financial misreporting. If CEO legal expertise plays a role in enhancing corporate financial reporting quality and reducing information asymmetry, it will likely affect audit risks and audit fees, in line with the findings of Danielsen et al. (2007) and Engel et al. (2010). Second, the auditing literature suggests that client business risk is among the primary risks assessed by auditors (Morgan and Stocken 1998; Bell et al. 2001). Given that lawyer CEOs reduce corporate risk, auditors could consider this in the pricing of their services.

We source audit fee data and other standard control variables from the Audit Analytics database. We measure audit fees, LN(AUDIT_FEE), as the logarithm of the audit fees (in US dollars) the firm pays its auditors over the fiscal year. Follow the auditing literature (e.g., Simunic 1980; Gul and Goodwin 2010; Bentley et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2015), we include control variables for firm characteristics and auditor characteristics, including firm size (LNSIZE), leverage (LEVERAGE), firm profitability (ROA), the market-to-book ratio (MTB), operating losses (LOSS), capital intensity (CAP_INTEN), interest coverage (INT_COV), the logarithm of non-audit fees (LN_NONFEE), a dummy variable (YE) that is equal to one if the firm’s fiscal year-end is December and zero otherwise, a dummy variable (BIG4) that takes the value of one if the firm is audited by one of the Big Four auditors and zero otherwise, audit opinion (OPINION), auditor tenure (AUDITOR_TENURE), and special items (SI). We account for differences in firms’ debt structure by including an indicator variable, SUBORD, which equals one if the firm has subordinated debt and zero otherwise (e.g., Kaplan and Urwitz 1979; Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2006). We also include the number of analysts following a firm (LNANALYST) (Gotti et al. 2012). We further include the standard deviation of earnings (EVOL), cash flows (STDCFO), and stock returns (RETVOL) to control for profitability and operating risks (Billings et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2015; Correia et al. 2018).

Finally, we further control for other CEO characteristics and other management attributes as in the baseline model (Table 2, Model (4)). We control for year fixed effects to control for time-invariant factors that could be associated with audit pricing. To avoid industry-specific effects from affecting variations in audit fees, we follow the audit pricing literature and control for industry fixed effects (e.g., Simunic 1980; Chen et al. 2015). We also lag all independent variables by one year, relative to the audit fee measures, to avoid potential reverse causality issues. Table 10 presents the results for the association between lawyer CEOs and audit fees.

We find the coefficient estimates for the LAWYER_CEO variable are negative and significant in both models in Table 10, suggesting that CEOs’ legal expertise reduces audit prices. The magnitude of the effect of CEO legal expertise on audit pricing is economically significant, with firms led by lawyer CEOs, on average, paying about 5% lower fees than firms headed by nonlawyer CEOs. Taken together, the results in Table 10 support our findings from Table 6 that the legal expertise of CEOs can influence their firms’ credit rating assessments by reducing future outcome risk and nurturing corporate information transparency.

7 Conclusion

We find that debt market participants incorporate reductions in future outcome risk and enhancements in corporate information environment associated with executives’ legal expertise into their assessments of a firm’s credit risk. Firms led by lawyer CEOs enjoy higher credit ratings than peers. We further document that executives’ legal expertise has implications for debt market investors and auditors. Firms led by lawyer CEOs, on average, have about 10% (about 19 bps) lower costs of debt than firms headed by nonlawyer CEOs. Auditors also value CEO legal expertise in the pricing of their services.

Notes

Bancel and Mittoo (2004) find a similar result for European chief financial officers (CFOs) and other financial managers. A total of 39% of the investors surveyed by Brown et al. (2019) deemed the credit ratings of the companies in which they invest or are contemplating investing in to be important.

For example, S&P downgraded General Electric’s credit rating from A to BBB+ a day after the company announced the firing of its CEO (https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/02/ge-credit-rating-under-review-for-possible-downgrade moodys.html).

Standard & Poor’s (2004, p. 120) corporate rating criteria also suggest the impact of information risk on corporate default risk: “Qualms about data quality would translate into a lower rating and preclude a rating in the upper part of the rating spectrum.”

We follow Kwak et al. (2012) and consider the following titles on ExecuComp as general counsel: general counsel, chief legal officer, chief legal executive, chief legal counsel, chief counsel, VP counsel, vice president for law and public affairs, vice president for law and government affairs, vice president for law and corporate affairs, vice president for legal affairs, and vice president of corporate affairs.

The sample for model (5) ends in 2018 because of the availability of the managerial ability data. We thank Peter Demerjian, Sarah McVay, and Baruch Lev for generously sharing their managerial ability data.

Our findings also align with those of Hopkins et al. (2015), who find that firms with highly compensated general counsels have lower financial reporting quality and more aggressive accounting practices.

We also perform an unreported test for the annual credit rating changes around the CEO turnover. The results are robust to the change of the event window.

We thank the editor for suggesting this figure.

We estimate this difference as the coefficient on LAWYER_CEO divided by the mean of the sample bond spread (e.g., −0.19/ 1.87 = 10%).

We also attempt to conduct the CEO turnover test for the bond spread sample. Specifically, we follow Bonsall IV et al. (2017) and examine a sample of CEO turnovers with the necessary bond spread data and control variables during our sample period. However, we could only identify five CEO turnovers with the necessary data, which does not allow us to repeat our CEO turnover analysis in the bond spread regressions.

We thank the referee for suggesting this analysis.

We thank the referee for suggesting this test.

The results from the path analyses in Table 6 suggest that lawyer CEOs have a significant direct effect on their firms’ credit ratings. We attempt to explore how lawyer CEOs can directly influence their firms’ credit risk assessments. A recent study by Pham (2020) suggests that the legal expertise of CEOs can enhance investors’ trust, such that their investment decisions favor firms led by lawyer CEOs. Consistent with this line of argument, we conjecture that the trust-building credibility of lawyer CEOs plays significant roles in shaping the risk profile of the firms they manage. Since trust underlies almost all economic transactions (Arrow 1972, 1974; Williamson 1993) and can influence risk assessment (Guiso et al. 2008; Georgarakos and Pasini 2011), credit rating agencies are likely to consider such soft information in their credit risk assessments. We thank the referee for suggesting this possibility.

Compared to firms led by nonlawyer CEOs, firms with lawyer CEOs have on average 10.80% or 17-bps (= 10.80% × 157 bps) lower CDS spread.

We thank the editor for suggesting this figure.

For each firm-year, earnings transparency is the sum of two R2 values, with the first R2 value constructed from annual returns-earnings relations estimated by industry and the second R2 value constructed from the annual return-earnings relation estimated by portfolio. We then create an indicator, HIGH_TRANS, that equals one if the firm’s transparency measure is above the sample median and zero otherwise

We thank Lalitha Naveen for making the co-opted board data available at https://sites.temple.edu/lnaveen/data.

References

Alissa, W., S.B. Bonsall IV, K. Koharki, and M.W. Penn Jr. 2013. Firms’ use of accounting discretion to influence their credit ratings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 55 (2–3): 129–147.

Armstrong, C.S., W.R. Guay, and J.P. Weber. 2010. The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2–3): 179–234.

Armstrong, C., K. Balakrishnan, and D. Cohen. 2012. Corporate governance and the information environment: Evidence from state antitakeover laws. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53: 185–204.

Arrow, K.J. 1972. Gifts and exchanges. Philosophy and Public Affairs 1 (4): 343–362.

Arrow, K.J. 1974. The limits of organization. W. W. Norton.

Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., D.W. Collins, and R. LaFond. 2006. The effects of corporate governance on firms' credit ratings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42 (1–2): 203–243.

Bamber, L.S., J. Jiang, and I.Y. Wang. 2010. What’s my style? The influence of top managers on voluntary corporate financial disclosure. The Accounting Review 85 (4): 1131–1162.

Bancel, F., and U. Mittoo. 2004. Cross-country determinants of capital structure choice: A survey of European firms. Financial Management 33: 103–132.

Barth, M.E., Y. Konchitchki, and W.R. Landsman. 2013. Cost of capital and earnings transparency. Journal of Accounting and Economics 55 (2–3): 206–224.

Bartov, E., and G.M. Bodnar. 1996. Alternative accounting methods, information asymmetry, and liquidity: Theory and evidence. The Accounting Review 91 (1): 69–98.

Bell, T.B., W.R. Landsman, and D.A. Shackelford. 2001. Auditors’ perceived business risk and audit fees: Analysis and evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 39 (1): 35–43.

Bentley, K.A., T.C. Omer, and N.Y. Sharp. 2013. Business strategy, financial reporting irregularities, and audit effort. Contemporary Accounting Research 30 (2): 780–817.

Bernile, G., V. Bhagwat, and P.R. Rau. 2017. What doesn’t kill you will only make you more risk-loving: Early-life disasters and CEO behavior. The Journal of Finance 72 (1): 167–206.

Bertrand, M., and A. Schoar. 2003. Managing with style: The effect of managers on firm policies. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 1169–1208.

Bharath, S.T., and T. Shumway. 2008. Forecasting default with the Merton distance to default model. Review of Financial Studies 21 (3): 1339–1369.

Bhojraj, S., and P. Sengupta. 2003. Effect of corporate governance on bond ratings and yields: The role of institutional investors and outside directors. Journal of Business 76 (3): 455–475.

Billings, B.A., X. Gao, and Y. Jia. 2014. CEO and CFO equity incentives and the pricing of audit services. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 33 (2): 1–25.

Blume, M.E., F. Lim, and A.C. MacKinlay. 1998. The declining credit quality of US corporate debt: Myth or reality? The Journal of Finance 53 (4): 1389–1413.

Bonsall, S.B., IV, E.R. Holzman, and B.P. Miller. 2017. Managerial ability and credit risk assessment. Management Science 63 (5): 1425–1449.

Brogaard, J., D. Li, and Y. Xia. 2017. Stock liquidity and default risk. Journal of Financial Economics 124 (3): 486–502.

Brown, S., M. Dutordoir, C. Veld, and Y. Veld-Merkoulova. 2019. What is the role of institutional investors in corporate capital structure decisions? A survey analysis. Journal of Corporate Finance 58: 270–286.

Cain, M.D., S.B. McKeon, and S.D. Solomon. 2017. Do takeover laws matter? Evidence from five decades of hostile takeovers. Journal of Financial Economics 124 (3): 464–485.

Cameron, A.C., J.B. Gelbach, and D.L. Miller. 2011. Robust inference with multiway clustering. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 29 (2): 238–249.

Chen, Y., F.A. Gul, M. Veeraraghavan, and L. Zolotoy. 2015. Executive equity risk-taking incentives and audit pricing. The Accounting Review 90 (6): 2205–2234.

Cheng, M., and K.R. Subramanyam. 2008. Analyst following and credit ratings. Contemporary Accounting Research 25 (4): 1007–1044.

Coles, J.L., N.D. Daniel, and L. Naveen. 2006. Managerial incentives and risk-taking. Journal of Financial Economics 79 (2): 431–468.

Coles, J.L., N.D. Daniel, and L. Naveen. 2014. Co-opted boards. Review of Financial Studies 27 (6): 1751–1796.

Core, J., and W. Guay. 2002. Estimating the value of employee stock option portfolios and their sensitivities to price and volatility. Journal of Accounting Research 40: 613–630.

Cornaggia, J., G.V. Krishnan, and C. Wang. 2017. Managerial ability and credit ratings. Contemporary Accounting Research 34 (4): 2094–2122.

Correia, M., J. Kang, and S. Richardson. 2018. Asset volatility. Review of Accounting Studies 23 (1): 37–94.

Corwin, S.A., and P. Schultz. 2012. A simple way to estimate bid-ask spreads from daily high and low prices. The Journal of Finance 67 (2): 719–760.

Cronqvist, H., and F. Yu. 2017. Shaped by their daughters: Executives, female socialization, and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Financial Economics 126 (3): 543–562.

Dahya, J., O. Dimitrov, and J.J. McConnell. 2008. Dominant shareholders, corporate boards, and corporate value: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Financial Economics 87 (1): 73–100.

Danielsen, B.R., R.A. Van Ness, and R.S. Warr. 2007. Auditor fees, market microstructure, and firm transparency. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 34 (1–2): 202–221.

Dechow, P.M., R.G. Sloan, and A.P. Sweeney. 1995. Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review 70 (2): 193–225.

DeFond, M.L., C.Y. Lim, and Y. Zang. 2016. Client conservatism and auditor-client contracting. The Accounting Review 91 (1): 69–98.

Demerjian, P., B. Lev, and S. McVay. 2012. Quantifying managerial ability: A new measure and validity tests. Management Science 58 (7): 1229–1248.

Diamond, D.W., and R.E. Verrecchia. 1991. Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance 46 (4): 1325–1359.

Dimitrov, V., D. Palia, and L. Tang. 2015. Impact of the Dodd-frank act on credit ratings. Journal of Financial Economics 115 (3): 505–520.

Engel, E., R.M. Hayes, and X. Wang. 2010. Audit committee compensation and the demand for monitoring of the financial reporting process. Journal of Accounting and Economics 49 (1–2): 136–154.

Francis, J., R. LaFond, P. Olsson, and K. Schipper. 2005. The market pricing of accruals quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39 (2): 295–327.

Francis, J., D. Nanda, and P. Olsson. 2008. Voluntary disclosure, earnings quality, and cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research 46 (1): 53–99.

Frankel, R., and X. Li. 2004. Characteristics of a firm’s information environment and the information asymmetry between insiders and outsiders. Journal of Accounting and Economics 37 (2): 229–259.

Ge, W., and M. Liu. 2015. Corporate social responsibility and the cost of corporate bonds. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 34 (6): 597–624.

Georgarakos, D., and G. Pasini. 2011. Trust, sociability, and stock market participation. Review of Finance 15: 693–725.

Gompers, P., J. Ishii, and A. Metrick. 2003. Corporate governance and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 107–156.

Gopalan, R., F. Song, and V. Yerramilli. 2014. Debt maturity structure and credit quality. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 49 (4): 817–842.

Gotti, G., S. Han, J.L. Higgs, and T. Kang. 2012. Managerial stock ownership, analyst coverage, and audit fee. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance 27 (3): 412–437.

Gow, I.D., G. Ormazabal, and D.J. Taylor. 2010. Correcting for cross-sectional and time-series dependence in accounting research. The Accounting Review 85 (2): 483–512.

Graham, J.R., and C.R. Harvey. 2001. The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. Journal of Financial Economics 60 (2–3): 187–243.

Guiso, L., P. Sapienza, and L. Zingales. 2008. Trusting the stock market. The Journal of Finance 63 (6): 2557–2600.

Gul, F.A., and J. Goodwin. 2010. Short-term debt maturity structures, credit ratings, and the pricing of audit services. The Accounting Review 85 (3): 877–909.

Ham, C., and K. Koharki. 2016. The association between corporate general counsel and firm credit risk. Journal of Accounting and Economics 61 (2–3): 274–293.

Hazarika, S., J.M. Karpoff, and R. Nahata. 2012. Internal corporate governance, CEO turnover, and earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics 104 (1): 44–69.

Henderson, M. T., Hutton, I., Jiang, D., and Pierson, M. 2018. Lawyer CEOs. Working paper, University of Chicago. Available at SSRN 2923136

Hoberg, G., and G. Phillips. 2010. Product market synergies and competition in mergers and acquisitions: A text-based analysis. Review of Financial Studies 23 (10): 3773–3811.

Hoberg, G., G. Phillips, and N. Prabhala. 2014. Product market threats, payouts, and financial flexibility. The Journal of Finance 69 (1): 293–324.

Hopkins, J.J., E.L. Maydew, and M. Venkatachalam. 2015. Corporate general counsel and financial reporting quality. Management Science 61 (1): 129–145.

Hutton, A.P., A.J. Marcus, and H. Tehranian. 2009. Opaque financial reports, R2, and crash risk. Journal of Financial Economics 94 (1): 67–86.

Jagolinzer, A.D., D.F. Larcker, and D.J. Taylor. 2011. Corporate governance and the information content of insider trades. Journal of Accounting Research 49 (5): 1249–1274.

Jiang, C., M.B. Wintoki, and Y. Xi. 2021. Insider trading and the legal expertise of corporate executives. Journal of Banking and Finance 127: 106–114.

John, K., L. Litov, and B. Yeung. 2008. Corporate governance and risk-taking. The Journal of Finance 63 (4): 1679–1728.

Jones, J.J. 1991. Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (2): 193–228.

Kabir, R., H. Li, and Y. Veld-Merkoulova. 2013. Executive compensation and the cost of debt. Journal of Banking and Finance 37 (8): 2893–2907.

Kaplan, R.S., and G. Urwitz. 1979. Statistical models of bond ratings: A methodological inquiry. Journal of Business 52 (2): 231–261.

Kaplan, S.N., and L. Zingales. 1997. Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financing constraints? Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (1): 169–215.

Kempf, E., and Tsoutsoura, M. 2021. Partisan professionals: Evidence from credit rating analysts. The Journal of Finance, 76(6), 2805–2856.

Kim, J.B., and L. Zhang. 2016. Accounting conservatism and stock price crash risk: Firm-level evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research 33 (1): 412–441.

Kim, S., P. Kraft, and S.G. Ryan. 2013. Financial statement comparability and credit risk. Review of Accounting Studies 18 (3): 783–823.

Kisgen, D.J. 2007. The influence of credit ratings on corporate capital structure decisions. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 19 (3): 65–73.

Klock, M.S., S.A. Mansi, and W.F. Maxwell. 2005. Does corporate governance matter to bondholders? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 40 (4): 693–719.

Krishnan, J., Y. Wen, and W. Zhao. 2011. Legal expertise on corporate audit committees and financial reporting quality. The Accounting Review 86 (6): 2099–2130.

Kuang, Y.F., and B. Qin. 2013. Credit ratings and CEO risk-taking incentives. Contemporary Accounting Research 30 (4): 1524–1559.

Kwak, B., B.T. Ro, and I. Suk. 2012. The composition of top management with general counsel and voluntary information disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics 54 (1): 19–41.

Lamont, O., C. Polk, and J. Saaá-Requejo. 2001. Financial constraints and stock returns. Review of Financial Studies 14 (2): 529–554.

Landsman, W.R., E.L. Maydew, and J.R. Thornock. 2012. The information content of annual earnings announcements and mandatory adoption of IFRS. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53 (1–2): 34–54.

Lang, M., K.V. Lins, and M. Maffett. 2012. Transparency, liquidity, and valuation: International evidence on when transparency matters most. Journal of Accounting Research 50 (3): 729–774.

Leuz, C., and R.E. Verrecchia. 2000. The economic consequences of increased disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research 38: 91–124.

Malmendier, U., and G. Tate. 2005. CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The Journal of Finance 60 (6): 2661–2700.

Malmendier, U., G. Tate, and J. Yan. 2011. Overconfidence and early-life experiences: The effect of managerial traits on corporate financial policies. The Journal of Finance 66 (5): 1687–1733.

Merton, R.C. 1974. On the pricing of corporate debt: The risk structure of interest rates. The Journal of Finance 29 (2): 449–470.

Micu, M., Remolona, E., and Wooldridge, P. 2006. The price impact of rating announcements: Which announcements matter? Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Working Paper (No. 207).

Morgan, J., and P. Stocken. 1998. The effects of business risk on audit pricing. Review of Accounting Studies 3 (4): 365–385.

Morse, A., W. Wang, and S. Wu. 2016. Executive lawyers: Gatekeepers or strategic officers? Journal of Law and Economics 59 (4): 847–888.

Oikonomou, I., C. Brooks, and S. Pavelin. 2014. The effects of corporate social performance on the cost of corporate debt and credit ratings. Financial Review 49 (1): 49–75.

Petersen, M.A. 2009. Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies 22 (1): 435–480.

Pham, H. 2020. In law we trust: Lawyer CEOs and stock liquidity. Journal of Financial Markets 50: 100548.

Simunic, D.A. 1980. The pricing of audit services: Theory and evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 18(1): 161–190.

Sloan, R.G. 1996. Do stock prices fully reflect information in accruals and cash flows about future earnings? The Accounting Review: 289–315.

Sobel, M.E. 1982. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology 13: 290–312.

Standard & Poor’s. 2002. Understanding credit ratings. January 1–4.

Standard & Poor’s. 2004. Standard & Poor’s corporate governance scores: Criteria, methodology and definitions. McGraw-Hill.

Thompson, S.B. 2011. Simple formulas for standard errors that cluster by both firm and time. Journal of Financial Economics 99 (1): 1–10.

Williamson, O.E. 1993. Calculativeness, trust, and economic organization. Journal of Law and Economics 36 (1, part 2): 453–486.

Zhang, B.Y., H. Zhou, and H. Zhu. 2009. Explaining credit default swap spreads with the equity volatility and jump risks of individual firms. Review of Financial Studies 22 (12): 5099–5131.