Abstract

Standard-setters worldwide have passed new audit reporting requirements aimed at making audit reports more informative to investors. In the UK, the new standard expands the audit reporting model by requiring auditors to disclose the risks of material misstatement (RMMs) that had the greatest effect on the financial statement audit. Using short window tests, prior research indicates that these disclosures are not incrementally informative to investors (Gutierrez et al. in Review of Accounting Studies 23:1543–1587, 2018). In this study, we investigate three potential explanations for why investors do not find the additional auditor risk disclosures to be informative. First, using long-window tests, we find no evidence that the insignificant short-window market reactions are due to a delayed investor reaction to RMMs. Second, using value relevance tests, we show that the insignificant market reactions are not due to auditors disclosing irrelevant information. Finally, we provide evidence suggesting that RMMs lack information content because investors were already informed about the financial reporting risks before auditors began disclosing them in expanded audit reports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Financial Reporting Council also requires auditors to disclose materiality thresholds. Our tests focus on the risk disclosures rather than materiality disclosures because the risk disclosures are common to the proposed or effective revisions to audit reporting standards issued by all the relevant standard-setters and regulators (i.e., the PCAOB, IAASB, and European Commission).

The FRC announced the new audit reporting standard in June 2013, less than 4 months before the expanded audit reports were required. The late announcement provided little time for companies or auditors to pre-empt the new standard with additional risk disclosures in the prior fiscal year. Moreover, audit firms and companies were opposed to the expanded model of audit reporting (New York Times 2014), which reduces the likelihood of voluntary early adoption. There is only one observation in our sample where an auditor provides risk disclosures prior to the required implementation date; our results are robust to dropping this company.

Companies House is a central depository where every company incorporated in the UK is required to file its accounts. Premium-listed companies incorporated in Jersey, Guernsey, The Isle of Man, and Ireland are not required to file their accounts at Companies House, so we obtain their annual reports from their websites.

UK companies typically release their annual reports after announcing their earnings. We obtain the annual report release dates from the London Stock Exchange website (www.londonstockexchange.com/prices-and-markets/markets/prices.htm), Morningstar (www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/NSM), ADVFN.com, and companies’ websites. In a few cases, we cannot identify the annual report release date. In these cases, we use the announcement of the Annual General Meeting (AGM) or the date of the actual AGM, because many companies release their annual reports at the same time that they announce or hold their AGMs. We perform sensitivity tests to ensure that our results are robust to excluding the companies with only AGM dates.

To alleviate concerns that the insignificant results may be due to a lack of statistical power, we perform a power analysis to determine how small a market reaction we could detect with our sample. We find we have adequate power to detect a statistically significant coefficient for RMM (when CAR is the dependent variable) that is greater than or equal to 0.00187, implying a market reaction (CAR) to an additional RMM that is greater than or equal to 0.187%. The corresponding statistic when |CAR| is the dependent variable is an effect size that is greater than or equal to 0.136% (both using one-tailed tests and power equal to 0.80). Because the economic magnitude of these effect sizes is so small, we believe we have adequate power to detect an economically meaningful market reaction to RMMs, if one exists.

The significant positive coefficient on RMM reflects that larger companies receive more RMMs (see Table 11 in Appendix C) and larger companies tend to have higher stock prices. However, the main effect in these models captures the effect of RMM when earnings or book value equals zero, which is not meaningful.

We also examine whether RMMs are predictive of future ROA and future CFO. After dropping the interaction terms (ROAit × RMMit and CFOit × RMMit), we find that RMMs are negatively associated with future CFO but not future ROA.

We perform one additional test to further ensure that the market already knew about the RMM information. Specifically, we convert Model 2 into a changes model where change in price from year t-1 to year t is the dependent variable and unexpected earnings (year-over-year change from year t-1 to year t) and unexpected RMMs (RMM_UE) are the independent variables of interest. We do not find significant coefficients on unexpected earnings, unexpected RMMs, or the interaction term, indicating that the market was already aware of the RMM information. We thank the editor for suggesting this additional test.

We obtain all available prior earnings announcements and conference call transcripts from company websites, Datastream, and the Thomson Reuters Eikon database. While not all conference call transcripts were available, we do not expect the missing reports to affect our inferences because most of the “already disclosed” disclosures were identified in prior earnings announcements or prior annual reports rather than in prior conference calls.

In Table 9, we have sufficient power to detect a significant coefficient for a new RMM in the CAR analysis that is greater than or equal to − 0.003 (i.e., a market reaction of − 0.3%) at conventional levels (alpha equal to 0.05 and power equal to 80%). The corresponding effect size for |CAR| is a market reaction to a new RMM that is greater than or equal to − 0.22%. Due to the small economic magnitude of these effect sizes, we conclude that we have adequate power to detect an economically meaningful market reaction, if one existed.

References

Andreicovici, I., A. Jeny, and D. Lui. (2020). Do firms respond to auditors’ red flags? Evidence from the expanded audit report. Working paper, Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, IESEG, and ESSEC. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3634479. Accessed 7 Oct 2020.

Barth, M. (1991). Relative measurement errors among alternative pension asset and liability measures. The Accounting Review 66 (3): 433–463.

Barth, M., W. Beaver, and W. Landsman. (2001). The relevance of the value relevance literature for financial accounting standard setting: Another view. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31: 77–104.

Boolaky, P.K., and R. Quick. (2016). Bank directors’ perceptions of expanded auditors’ reports. International Journal of Auditing 20: 158–174.

Burke, J., R. Hoitash, U Hoitash, and X. Xiao. (2020). An investigation of U.S. critical audit matter disclosures. Working paper, University of Colorado Denver, Bentley University, and Northeastern University. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3635477. Accessed 7 Jun 2021.

Chen, F., S. Peng, S. Xue, Z. Yang, and F. Ye. (2016). Do audit clients successfully engage in opinion shopping? Partner-Level Evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 54 (1): 79–112.

Chow, C., and S. Rice. (1982). Qualified audit opinions and share prices—An investigation. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 1 (2): 35–53.

Christensen, B., S. Glover, and C. Wolfe. (2014). Do critical audit matter paragraphs in the audit report change nonprofessional investors’ decision to invest? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 33: 71–93.

Church, B., S. Davis, and S. McCracken. (2008). The auditor’s reporting model: A literature overview and research synthesis. Accounting Horizons 22 (1): 69–90.

Czerney, K.J., J.J. Schmidt, and A. Thompson. (2018). Do investors respond to explanatory language included in unqualified audit reports? Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (1): 198–221.

Dodd, P., N. Dopuch, R. Holthausen, and R. Leftwich. (1984). Qualified audit opinions and stock prices. Journal of Accounting and Economics 6 (1): 3–38.

Doyle, J., W. Ge, and S. McVay. (2007). Determinants of weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 44: 193–223.

Drake, K., N. Goldman, S. Lusch, and J. Schmidt. (2020). Have critical audit matter disclosures indirectly benefitted investors by constraining earnings management? Evidence from tax accounts. Working paper, University of Arizona, North Carolina State University, Texas Christian University, and the University of Texas at Austin. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3606701. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

Elliott, J.A. (1982). “Subject to” audit opinions and abnormal security returns—outcomes and ambiguities. Journal of Accounting Research 20 (2): 617–638.

European Commission. (2010). Green Paper. Audit Policy: Lessons from the Crisis (October 2010). http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/auditing/otherdocs/index_en.htm. Accessed 2 Apr 2015.

Feltham, G., and J. Ohlson. (1995). Valuation and clean surplus accounting for operating and financial activities. Contemporary Accounting Research 11 (2): 689–731.

Files, R. and P. Gencer. (2020). Investor response to critical audit matter (CAM) disclosures. Working paper, University of Texas at Dallas. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3532754. Accessed 11 Mar 2020.

Financial Reporting Council (FRC). (2013). Consultation paper: Revision to ISA (UK and Ireland) 700—Requiring the auditor’s report to address risks of material misstatement, materiality, and a summary of the audit scope. London: Financial Reporting Council.

Financial Reporting Council (FRC). (2016). Extended auditors’ reports: A further review of experience. London: Financial Reporting Council.

Gray, G., J. Turner, P. Coram, and T. Mock. (2011). Perceptions and misperceptions regarding the unqualified auditor’s report by financial statement preparers, users, and auditors. Accounting Horizons 25 (4): 659–684.

Gutierrez, E., M. Minutti-Meza, K.W. Tatum, and M. Vulcheva. (2018). Consequences of adopting an expanded auditor’s report in the United Kingdom. Review of Accounting Studies 23: 1543–1587.

Gutierrez, E., M. Minutti-Meza, K.W. Tatum, and M. Vulcheva. (2021). Consequences of the expanded audit report for small and high-risk companies: Evidence from the United Kingdom’s Alternative Investment Market. Working paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3805879. Accessed 7 Jun 2021.

Holthausen, R.W., and R.E. Verrecchia. (1988). The effect of sequential information releases on the variance of price changes in an intertemporal multi-asset market. Journal of Accounting Research 26 (1): 82–106.

International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). (2013). IAASB proposes standards to fundamentally transform the auditor's report; focuses on communicative value to users. IAASB Press Release New York, N.Y. (July 25). https://www.ifac.org/news-events/2013-07/iaasbproposes-standards-fundamentally-transform-auditors-report-focuses-communi. Accessed 25 Jul 2013.

International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). (2015). Reporting on Audited Financial Statements: New and Revised Auditor Reporting Standards and Related Conforming Amendments. https://www.iaasb.org/system/files/publications/files/Reporting-on-AFS-New-&-Revised-Stds-Combined_1.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2015.

Kachelmeier, S., D. Rimkus, J. Schmidt, and K. Valentine. (2020). The forewarning effect of critical audit matter disclosures involving measurement uncertainty. Contemporary Accounting Research 37: 2186.

Kausar, A., R. Taffler, and C. Tan. (2009). The going-concern market anomaly. Journal of Accounting Research 47 (1): 213–239.

Klueber, J., A. Gold, and C. Pott. (2018). Do key audit matters impact financial reporting behaviour? Working paper, TU Dortmund University and VU University Amsterdam. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3210475. Accessed 15 Apr 2020.

Kohler, A., N.V.S. Ratzinger-Sakel, and J. Theis. (2020). The effects of key audit matters on the auditor’s report’s communicative value: Experimental evidence from investment professionals and non-professional investors. Accounting in Europe 17: 105.

Landsman, W.R., W.L. Maydew, and J.R. Thornock. (2012). The information content of annual earnings announcements and mandatory adoption of IFRS. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53: 35–54.

Lennox, C. (2000). Do companies successfully engage in opinion-shopping? The UK experience. Journal of Accounting and Economics 29: 321–337.

Lennox, C. (2005). Audit quality and executive officers’ affiliations with CPA firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 201–231.

Liao, L., M. Minutti-Meza, Y. Zhang, and Y. Zou. (2019). Consequences of the adoption of the expanded auditor’s report: Evidence from Hong Kong. Working paper, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, University of Miami, and George Washington University. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3392449. Accessed 16 Jun 2021.

Loughran, T., and B. McDonald. (2011). When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. Journal of Finance 66: 35–65.

Minutti-Meza, M. (2020). The art of conversation: The expanded audit report. Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3709059. Accessed 12 Oct 2020.

New York Times. (2014). Holding auditors accountable on reports. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/09/business/holding-auditors-accountable.html?_r=2. Accessed 8 May 2014.

Newton, N., J. Persellin, D. Wang, and M. Wilkins. (2016). Internal control opinion shopping and audit market competition. The Accounting Review 91 (2): 603–623.

Ohlson, J. (1995). Earnings, book values, and dividends in equity valuation. Contemporary Accounting Research 11 (2): 661–687.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). (2013). Proposed auditing standards—the auditor’s report on an audit of financial statements when the auditor expresses an unqualified opinion; the auditor’s responsibilities regarding other information in certain documents containing audited financial statements and the related auditor’s report; and related amendments to PCAOB standards. PCAOB Release No. 2013–005, August 13, 2013.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). (2017). The auditor’s report on an audit of financial statements when the auditor expresses an unqualified opinion; and related amendments to PCAOB standards. PCAOB Release No. 2017–001, June 1, 2017.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). (2020). Interim analysis report: Evidence on the initial impact of critical audit matter requirements. PCAOB Release No. 2020–002, October 29, 2020.

Reid, C., J. Carcello, C. Li, and T.L. Neal. (2019). Impact of auditor report changes on financial reporting quality and audit costs: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (3): 1501–1539.

Santos, K., R. Guerra, V. Marques, and E. Junior. (2020). Do critical audit matters matter? An analysis of their association with Earnings Management. Journal of Education and Research in Accounting 14 (1): 55–77.

Sirois, L., J. Bédard, and P. Bera. (2020). The informational value of key audit matters in the auditor’s report: Evidence from an eye-tracking study. Accounting Horizons, forthcoming. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2469905. Accessed 25 May 2020.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark DeFond, Jere Francis, Chris Hogan, Bill Kinney, Jeff Pittman, Joe Schroeder (AAA discussant), Theodore Sougiannis, Mike Wilkins, and the workshop participants at Baylor University, the University of California at Riverside, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, the 2016 AAA Auditing Midyear Conference, and the 2016 International Symposium on Audit Research for their helpful comments and suggestions. We are grateful for research funding from the McCombs Research Excellence Grant Program and the McCombs Undergraduate Research Assistant Program. We thank Emily Baker, Sid Chandrashekar, Diana Choi, Jessie Hu, Minjae Kim, John Menefee, Catherine Quintana, Stephen Tran, Jinghua Xing, Tingya Hu, Julia Rossdeutscher, Ting-Ting Wang, Samantha Wendt, and Qiang Wei for their research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

See Table 10

.

Appendix B

Variable definitions

Dependent variables

CAR = 3-day cumulative abnormal return (− 1, 1) centered on company i’s annual report release date.

|CAR|= 3-day unsigned cumulative abnormal return (− 1, 1) centered on company i’s annual report release date.

VOLATILITY = abnormal 3-day stock return volatility (following Landsman et al. 2012).

VOLUME = abnormal 3-day trading volume (following Landsman et al. 2012).

Pit = company i’s stock price per share, 30 days after company i’s year t annual report release date.

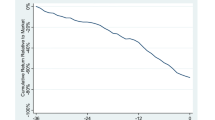

BHAR (1, 3, 6, 12 month) = buy and hold abnormal returns for company i calculated using the FTSEALL index over the window 1, 3, 6, or 12 months among observations with one full year of returns following the annual report release date.

AUD_CHANGEt+1 = one if company i changes auditors between year t and year t + 1, 0 otherwise.

ROAt+1 = return on assets for company i in year t + 1.

CFOt+1 = cash flow from operations scaled by total assets for company i in year t + 1.

Test variables

RMM = the number of risks of material misstatement disclosed in company i’s audit report.

RMM_ACCT = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s expanded audit report that pertain to specific accounts in the financial statements.

RMM_ENTITY = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s expanded audit report that pertain to the entity as a whole.

RMM_COMPANY = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s audit report that appear in fewer than 50% of the audit reports in company i’s industry in year t.

RMM_INDUSTRY = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s audit report that also appear in more than 50% of the audit reports in company i’s industry in year t.

RMM_PRED = the predicted number of RMMs for company i in year t from the model shown in Column 1 of Appendix C.

RMM_UE = the residual from estimating the model shown in Column 1 of Appendix C that predicts the number of RMMs in company i’s audit report in year t.

RMM_TONE = the number of positive words in the RMM section of company i’s audit report less the number of negative words in the RMM section of company i’s audit report, scaled by total words in company i’s RMM section. Positive and negative words follow the 2014 update to the Loughran and McDonald (2011) word lists.

RMM_CHANGE = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s year t audit report minus the number of RMMs reported in company i’s year t-1 audit report.

RMM_PREV = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s year t audit report that were previously reported by the auditor in year t-1. In year 1, RMM_PREV = 0 because year 1 is the first year of RMM disclosure. In year 2, RMM_PREV = RMM_NEW_Y2 because we use the year 1 audit report to identify any new RMMs in the following year.

RMM_NPREV = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s year t audit report that were not previously reported by the auditor in year t-1. In year 1, RMM_NPREV = RMM because year 1 is the first year of RMM disclosure. In year 2, RMM_NPREV = RMM_AD_Y2 because we use the year 1 audit report to identify any new RMMs in the following year.

RMM_NEW_Y1 = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s year 1 audit report where we are unable to find that the company previously disclosed the risk in the prior year.

RMM_AD_Y1 = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s year 1 audit report where we find that the company previously disclosed the risk in the prior year.

RMM_NEW_Y2 = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s year 2 audit report that were not disclosed by the auditor in year 1.

RMM_AD_Y2 = the number of RMMs reported in company i’s year 2 audit report that were already disclosed by the auditor in year 1.

RMM_NEW_Y1&Y2 = RMM_NEW_Y1 in year 1 or RMM_NEW_Y2 in year 2.

RMM_AD_Y1&Y2 = RMM_AD_Y1 in year 1 or RMM_AD_Y2 in year 2.

Control variables

ANALYSTS = the number of analysts following company i in year t.

ACQ = acquisitions amount divided by total assets for company i in year t. Missing values are set equal to zero.

AC_SIZE = audit committee size for company i in the first year of adoption.

BTM = the book to market ratio for company i at the end of year t.

BUSY = one if company i has a December year-end and zero otherwise.

BV = net assets per share for company i at the end of year t.

CATA = current assets divided by total assets for company i in year t.

DEF_TAX = deferred taxes scaled by total assets for company i in year t. Missing deferred tax accruals are set equal to zero.

DISTRESS = one if company i reports a negative value for net income or net assets in year t and zero otherwise.

E = earnings per share for company i in year t.

EXTR_ITEMS = extraordinary items scaled by total assets for company i in year t. Missing values are set equal to 0.

FIXED ASSETS = net fixed assets scaled by total assets for company i in year t.

GC = one if company i’s audit report includes an RMM or report modification indicating substantial doubt about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern and zero otherwise.

GOODWILL = goodwill scaled by total assets for company i in year t.

INVENTORY = inventory scaled by total assets for company i in year t.

LAG_ACQ = acquisitions amount for company i in the prior year scaled by total assets in the prior year.

SIZE = the natural log of the market value of equity for company i at the end of year t.

LN_SUBS = the natural log of (one plus) the total number of subsidiaries for company i in year t.

LOSS = one if company i reported a loss in year t and zero otherwise.

PROBLEM = one if company i had an accounting problem during the two years prior to year t’s audit report and zero otherwise. We identify a company as having had an accounting problem if it announced a restatement to correct a previous error or irregularity or if the company was named by the Financial Reporting Council as having had an accounting problem.

RECEIVABLES = accounts receivable scaled by total assets for company i in year t.

SALESGROWTH = percentage change in revenue for company i from year t-1 to year t.

SEC_REG = one if company i is registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and zero otherwise.

TENURE = the natural log of audit firm tenure for company i in year t.

UNCERTAINTY = the number of uncertainty words divided by total words in the risk of material misstatement section of company i’s audit report in year t. Uncertainty words are available at https://www3.nd.edu/~mcdonald/Word_Lists.html.

Notes: The RMM test variables—PROBLEM, SEC_REG, AC_SIZE, AUD_CHANGE, and AUDITOR_TENURE—are hand collected from companies’ annual reports and other sources. Market variables are constructed from Compustat Global. Other variables are sourced from FAME and Compustat Global, supplemented by hand collection as needed to avoid sample loss.

Appendix C

See Table 11.

Appendix D

5.1 Examples of previously disclosed risks of material misstatement

5.1.1 Example 1: Extract from the audit report issued by PricewaterhouseCoopers to ICAP plc in 2014

“Area of Focus.

Goodwill impairment assessment.

We focused on this area due to the size of the goodwill balance and because the directors’ assessment of the carrying value of the Group’s cash generating units (CGUs) involves judgements about the future results of the business and the discount rate applied to future cash flow forecasts.” (p. 91).

5.2 Extract from the intangible assets footnote in the 2013 annual report of ICAP plc

“This process requires the exercise of significant judgement by management; if the estimates made prove to be incorrect or performance does not meet expectations which affect the amount and timing of future cash flows, goodwill and intangible assets may become impaired in future periods.” (p. 98).

5.2.1 Example 2: Extract from the audit report issued by KPMG to Rathbone Brother plc on April 15, 2014

“The risk: Note 32 refers to two related legal claims that are ongoing. The directors have determined that no provision should be raised in respect of these claims as at 31 December 2013 as they believe that it is more likely than not that any final judgment in relation to these claims will not result in a liability against the group and, on this basis, have disclosed them as a contingent liability. Due to the complexity of the two cases and the risks concerning the sufficiency of the insurance cover, the assessment of whether a liability is probable, possible or remote is considered to be inherently subjective and the amounts involved are potentially material.” (p. 73).

5.3 Extract from the Rathbone Brothers plc earnings announcement issued on February 20, 2014

“Legal proceedings: As reported in the 2012 report and accounts, a claim relating to the management of a Jersey trust has been filed against a former employee (and director) of a former subsidiary and others (and that former subsidiary has recently been joined in as a defendant). In addition, the company issued proceedings against certain of its civil liability (professional indemnity) insurers in respect of the former employee’s potential liabilities arising out of the Jersey claim. In November 2013 the company announced that judgment had been handed down following the trial in the Commercial Court in London in respect of the insurance case. In December, the company and the former employee in question decided to appeal subrogation aspects of the judgment and our insurers also decided to appeal coverage aspects of the judgment. The hearing of those appeals before the Court of Appeal is expected to take place in the second half of 2014. The underlying Jersey claim is now expected to come to trial towards the end of 2015. Further detail on these matters is set out in note 8.”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lennox, C.S., Schmidt, J.J. & Thompson, A.M. Why are expanded audit reports not informative to investors? Evidence from the United Kingdom. Rev Account Stud 28, 497–532 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09650-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09650-4