Abstract

This study uses directors’ and officers’ (D&O) insurance data to examine the relation between tax aggressiveness and tax litigation risk. D&O insurance covers litigation costs for tax-related cases. Thus D&O insurance premiums provide an independent and direct assessment of the risk in a firm’s tax aggressive strategies, which mitigates some of the challenges in studying tax risk. Based on pricing decisions, D&O insurers appear to view tax aggressiveness, as measured by industry- and size-adjusted cash effective tax rates (a measure where higher rates are associated with more aggressiveness), as increasing tax-related litigation risk. Regarding tax uncertainty, premiums increase (decrease) as unrecognized tax benefits (UTB-related settlements with tax authorities) increase. Finally, D&O insurers focus on firms with outbound tax haven activity when pricing tax aggressiveness. Overall, this suggests D&O insurers include aspects of both low taxes and tax uncertainty when pricing tax litigation risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We focus on tax aggressiveness, as D&O insurers are more likely to price aggressive tax planning, rather than uncontroversial and more benign tax avoidance strategies. Blouin (2014) argues that tax aggressiveness is, by definition, risky. We complement her work by empirically testing whether and which measures of tax aggressiveness are associated with tax litigation risk. In addition, we define tax risk as any uncertainty about tax outcomes from activities the firm has either adopted or has chosen not to pursue (see Neuman et al. 2020).

For example, Shuffle Master Inc. settled a securities class action for $13 million related to tax-driven profit shifting, which equaled 37 (4) percent of the firm’s net income (assets), but it was paid in full by D&O insurers.

Results are robust to only examining tax-related litigation where the allegations relate to tax aggressiveness.

Donelson et al. (2015) estimate defense costs in securities class actions as 35% of settlement amounts.

The exceptions to the clear downward trend are approximately three years, 2002–2004, where revealed tax shelters spike, possibly due to the financial frauds of the early 2000s.

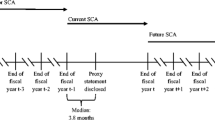

Using case filing data from Advisen and the Stanford Securities Class Action Clearinghouse for 1996–2016, we classify nontax-related litigation as cases (not in the tax-related litigation sample) that are either 1) SEC accounting cases alleging a Rule 10b-5 violation, 2) securities class actions alleging a Rule 10b-5 violation, or 3) derivative cases. We exclude initial public offering (IPO) allocation, mutual fund, and analyst cases (Kim and Skinner 2012).

We find similar results if we omit cases from 1998 and 2001, the two years in our sample with no tax-related litigation (untabulated). Specifically, the annual rate of nontax (tax-related) litigation increases by 30 (107) percent.

For example, widespread leaks about some firms’ use of offshore entities and “sweetheart” tax deals with certain countries (e.g., LuxLeaks and Panama Papers) may expose these firms to an increased risk of non-IRS tax-related litigation about explicit tax issues abroad (Marsh and McLennan 2017). Although the primary allegation(s) of many cases involves misreporting about explicit taxes in the financial statements, classifying these cases solely as tax reporting and disclosure would mischaracterize the underlying tax activity that prompted the case. For example, in 2007, shareholders filed a securities class action against Pall Corporation and certain officers and directors for misrepresenting the firm’s ETR in the financial statements. However, as the complaint reveals, the ETR was incorrect in the financial statements because one of the firm’s intercompany transactions, in which a foreign subsidiary of the firm sold products to a U.S. subsidiary, gave rise to deemed dividend income under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §956. Thus the firm owed the IRS roughly $130 million in unpaid taxes, and, because the underlying tax activity triggering the case dealt specifically with the firm’s explicit tax liability, we classify the case as focused on both explicit taxes and tax financial reporting accordingly. See Appendix A for additional case details.

We classify the tax issues in each case without regard to prominence (e.g., whether the allegation is the primary allegation in the case as shown in Panel B). Thus, although 63% of cases involve explicit tax issues, these issues can be the primary allegation, of equal importance to other (nontax) issues, or a secondary allegation.

Derivative litigation allows investors to sue in the corporation’s name against the firm’s managers. That is, if the corporation will not sue its managers, investors can do so with any proceeds remitted back to the corporation. For example, Wells Fargo investors filed a derivative suit alleging managers used sale in/lease out (SILO) tax shelters and failed to settle with the IRS during an amnesty period. Derivative litigation is often filed when the firm does not experience a steep stock price decline, which is usually necessary for securities class actions (Erickson 2011).

We are only aware of two such cases in our sample.

The SEC or DOJ can also bring litigation over tax issues under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). In these suits, firms are generally accused of bribing foreign government officials to avoid or reduce taxes. This type of litigation is also infrequent, as only 6% (seven cases) of cases in our sample were filed under the FCPA.

See Appendix A for more information on this case.

If a claim is settled out of court without an admission of bad faith (or there is no finding of bad faith if the claim goes to court), managers are assumed to have acted in good faith (Core 2000). There are three types of D&O insurance: side A, side B, and side C. side A reimburses managers when a firm is unwilling or unable to indemnify them. Side B reimburses the firm for costs it incurs in indemnifying managers. Side C covers direct claims against the firm (Chen et al. 2016). D&O insurance is widespread in the United States, as almost all firms have side A and side B coverage and around 75% have side C coverage (Towers Watson 2013).

For example, if a regulator alleges a firm violated environmental law on the disposal of toxic waste, “the investigation may take years to complete and may require thousands of hours worth of attorney fees. A D&O policy may cover the cost of the investigation, as well as any penalty levied by the government” (Business Benefits Group 2019). Similarly, Carter (2012) recommends D&O insurance that covers “not just lawsuits but also investigations, administrative proceedings and arbitrations” and notes this coverage is particularly desirable “since IRS, FTC, EEOC or similar investigations and proceedings can be costly.”

Whether D&O insurance would also cover defense costs incurred by the corporation in IRS litigation depends on the type of corporation and whether the litigation also targets any directors or officers. For most public companies, D&O insurance is unlikely to cover many of the costs associated with IRS litigation. Separately, “tax insurance” can insure the tax risk associated with the underlying tax liabilities, but this is beyond the scope of our study.

Informal discussions with D&O insurers and industry experts validate that D&O insurers price tax litigation risk, including consideration of whether a firm operates in low tax jurisdictions as well as for explicit tax issues where the insurer typically would not be liable for the unpaid taxes. For example, a D&O insurer noted that the stock options backdating scandal led to large tax bills for firms, which ultimately played a role in the subsequent litigation.

Anecdotal evidence validates that defense costs are significant. For example, after GlaxoSmithKline’s settlement with the IRS in a transfer pricing case, the firm’s CFO stated that the firm was confident it would prevail but settled due to the time and cost of litigation, which was expected to last two to three years (Matthews and Whalen 2006).

In addition, the different legal, tax, financial reporting, and insurance environments in the United States and Canada suggest the findings of Zeng (2017) may not describe how D&O insurers in the United States price firms’ tax information. Specifically, in contrast to Canadian settings, D&O insurance premiums in the United States are more expensive, due to the lack of risk-based pricing (Donelson et al. 2021), and firms’ premium and limit information is not publicly disclosed, which may affect managerial behavior (Chalmers et al. 2002). In addition, differences in the legal environments result in decreased litigation costs and lower litigation risk in Canada, affecting Canadian firms’ demand for D&O insurance. Consistent with differing D&O landscapes, Donelson et al. (2021) find that many inferences for the relation between agency costs and D&O insurance from the Canadian literature do not generalize to U.S. firms. Finally, there are significant differences in the tax environments that may affect both the desire and method for tax planning. For example, in contrast to the U.S. worldwide tax system, Canada’s territorial system only taxes income earned in Canada (Tax Foundation 2014).

As it is difficult to empirically assess the point at which tax planning transitions to tax aggressiveness, studies often use the same measures (e.g., cash ETRs) as encompassing both tax planning and aggressiveness.

Also potentially consistent with different relations between D&O insurance premiums and tax aggressiveness measures over time, several insurance firms acknowledge that their financial acuity and the thoroughness of the application process have grown over time (Baker and Griffith 2010). For example, D&O insurers often now employ forensic accountants to review the financial statements to identify any risks that may result in litigation.

GAAP ETR may not directly capture the construct of tax litigation risk, which is often proxied for using cash tax-based measures (e.g., Guenther et al. 2017), because it captures accruals relating to a firm’s tax positions, such as the assertion for permanently reinvested earnings (PRE), the FIN 48 reserve and adjustments to the valuation allowance for deferred tax assets. However, we include it in our analysis because it is unclear whether tax litigation risk encompasses some financial reporting aspect (Wilde and Wilson 2018).

Other tax-related events may have also contributed to a change in D&O insurers pricing of tax aggressiveness around this period. KPMG settled with the Department of Justice (2005) in the Contested Liability Acceleration Strategy tax shelter fraud and “admitted criminal wrongdoing and agreed to pay $456 million in fines, restitution and penalties as part of an agreement to defer prosecution.” This settlement showed tax issues could result in large settlements and may have attracted attention by plaintiffs’ lawyers and D&O insurers. Similarly, the stock option backdating scandal received significant public scrutiny after the “Perfect Payday” series in The Wall Street Journal in 2006 (Seelye and Barron 2007), which showed that tax-related misconduct (Chyz 2013) could result in successful government enforcement and shareholder litigation. Additionally, the IRS subsequently required the UTB-related disclosures (i.e., Schedule UTP), which could also increase litigation risk (LaCroix 2011).

Specifically, we compute the mean of all variables in equation (1) by year, orthogonalize TA_CASH and TA_GAAP to our control variables, and use Stata’s estab sbsingle to conduct the Supremum Wald test. Following Andrews (1993), we employ a symmetric trimming of 15%, due to an inability to estimate the parameters for possible breaks too near the beginning or end of the sample. We similarly reject the null of no structural break using average Wald and average likelihood ratio tests (p < 0.05, untabulated).

An alternative, nontax explanation for the shift in 2008 is the financial crisis. In particular, if there was a spike in PREM_LIMIT from the financial crisis concurrent with a significant decrease in pre-tax income, due to the recession, which is the scalar for our ETR variables, that could result in a spurious positive and significant association. We ensure the financial crisis is not driving our results in multiple untabulated ways. First, we observe that average PREM_LIMIT decreases throughout most of our post period, but this decrease begins in 2005 after a high in 2004. Thus this concern is unlikely. Second, we omit financial crisis years (2008–2009) and continue to find similar results in our main analyses. Third, we examine whether there is a shift regarding D&O insurers’ pricing of tax havens (see Table 9) from the pre- to post-period, since the financial crisis seems less likely to affect this analysis. We find that D&O insurers only focused on tax havens without economic substance in the pre-period but begin pricing tax havens with economic substance and other proxies for tax aggressiveness in the post-period, consistent with D&O insurers believing that a wider set of tax activities may constitute litigation risk in the post-period, which is consistent with our story but inconsistent with the financial crisis driving our results.

However, UTB and SETTLE are subject to certain limitations. For instance, UTBs may capture managerial discretion (De Simone et al. 2014; Towery 2017) and aspects of tax reporting. In addition, because our measure of settlements with tax authorities is based on the decrease in the UTB account, SETTLE depends on the firm creating a reserve for the tax position in the first place (Ciconte et al. 2016). Nonetheless, UTBs predictfuture tax cash outflows (Ciconte et al. 2016), so they may be useful signals to D&O insurers.

Results are similar if we omit TA_CASH when estimating equation (1) for UTB and SETTLE (untabulated).

Although we control for several factors associated with litigation, such as ex ante securities litigation risk, return volatility, firm losses, and year and industry fixed effects to capture time and industry trends in litigation, the increasing trend in nontax litigation over time may influence our results. In untabulated analysis, we re-perform our analyses after controlling for either 1) the natural logarithm of the three-year average of total settlements or 2) the natural logarithm of the three-year average of the total number of nontax-related litigation cases (as defined in footnote 7), both by the firm’s Fama-French 48 industry, measured at year t-1 and based on the disposition date of the case. Alternatively, we re-perform our analyses after omitting firm years in which a firm was sued for nontax litigation, with and without classifying tax-related litigation where tax allegations are of secondary importance as nontax litigation. In both cases, we find similar results.

As firms often carry multiple D&O policies, we group all firm policies based on the effective date and expiration date (Donelson et al. 2015). To mitigate self-selection concerns, we re-estimate analyses for only firm-years that Advisen collected from insurance brokers and wholesalers. Untabulated results are similar to those reported.

We follow standard practice and remove observations with a Cook’s Distance statistic in the top 4% of the sample (Leone et al. 2019). Alternatively, we find similar inferences if we use robust regression (untabulated).

Because we remove observations based on Cook’s D, the number of observations in regressions differ slightly.

Our analysis is still a subset of all tax litigation, however, because we only have D&O insurance data for some of the sued firms. However, results are similar if we use only cases remaining after all data screens (untabulated).

As noted, in untabulated analysis, we conduct a Supremum Wald test to test for a structural break, and we find a structural break between tax-related litigation and subsequent-year D&O insurance premiums in 2008 (p < 0.01).

We find similar results for both tests using robust regression or using all tax-related litigation cases, regardless of whether they are primarily focused on tax issues (untabulated).

In an untabulated analysis, we examine the standard deviation of cash ETRs (Guenther et al. 2017). We find similar inferences in all analyses if we control for it, and it has no significant relation with D&O insurance premiums.

Consistent with these results, we also find that current-year additions to the UTB account are positively and significantly associated with subsequent-year D&O insurance premiums (untabulated).

Because UTBs are only recently available, some studies use a predicted UTB measure, following Rego and Wilson (2012). In untabulated analysis, we also test the relation between predicted UTBs and D&O insurance for the pre- and post-periods. We fail to find a relation between predicted UTBs and D&O insurance premiums in either period, likely consistent with measurement error in the post-period and insurers not using this information in the pre-period.

Consistent with this, as shown in Panel C of Table 4, TA_FACTOR is positively correlated with TA_CASH, TA_GAAP, and UTB and negatively correlated with SETTLE (p < 0.01).

In untabulated analysis, we also test whether greater subsidiary tax haven intensity, as disclosed on a firm’s Exhibit 21, affects how D&O insurers price tax aggressiveness. Specifically, we create an alternative indicator variable set equal to one if the firm’s tax haven intensity is in the highest tercile of the distribution for that year and zero otherwise, computed similar to Dyreng et al. (2019) using Dyreng and Lindsey’s (2009) Exhibit 21 data and re-estimate the analysis. Disclosure of a tax haven subsidiary on a firm’s Exhibit 21 does not generally appear to affect how D&O insurers price firms’ industry-size adjusted ETRs, UTBs, or settlements. However, firms may strategically disclose tax haven subsidiaries (e.g., Dyreng et al. 2020) but would likely be required to disclose more complete information to their D&O insurers (Baker and Griffith 2010), so these tests may be less powerful.

We find similar inferences if we omit the second main effect (e.g., for tax havens without economic substance, we control only for the main effect of tax havens without economic substance), include firms that use both types of tax havens, or include interactions for both with and without economic substance in the same regression (untabulated).

References

Andrews, D.W.K. (1993). Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point. Econometrica 61 (4): 821–856.

Armstrong, C.S., J.L. Blouin, A.D. Jagolinzer, and D.F. Larcker. (2015). Corporate governance, incentives, and tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 60 (1): 1–17.

Atwood, T.J., and C. Lewellen. (2019). The complementarity between tax avoidance and manager diversion: Evidence from tax haven firms. Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (1): 259–294.

Baker, T., and S.J. Griffith. (2010). Ensuring corporate misconduct: How liability insurance undermines shareholder litigation. University of Chicago Press.

Baker McKenzie. (2020). United States: Securities claims and government investigations relating to COVID-19-D&O coverage considerations. April 23. Available at: https://www.bakermckenzie.com/en/insight/publications/2020/04/securities-claims-and-gov-investigations-covid19.

Balakrishnan, K., J.L. Blouin, and W.R. Guay. (2019). Tax aggressiveness and corporate transparency. The Accounting Review 94 (1): 45–69.

Black, D.E., S.S. Dikolli, and S.D. Dyreng. (2014). CEO pay-for-complexity and the risk of managerial diversion from multinational diversification. Contemporary Accounting Research 31 (1): 103–135.

Blouin, J.L. (2014). Defining and measuring tax planning aggressiveness. National Tax Journal 67 (4): 875–900.

Bozanic, Z., J.L. Hoopes, J.R. Thornock, and B. Williams. (2017). IRS attention. Journal of Accounting Research 55 (1): 79–114.

Business Benefits Group. (2019). Examples of D&O claims. Benefits Consulting. May 13. Available at: https://www.bbgbroker.com/examples-director-officer-claims/.

Carter, E. (2012). What to look for in a directors and officers’ insurance policy. CharityLawyer. June 19. Available at: https://charitylawyerblog.com/2012/06/19/what-to-look-for-in-a-directors-and-officers-insurance-policy/.

Cao, Z., and G.S. Narayanamoorthy. (2014). Accounting and litigation risk: Evidence from directors’ and officers’ insurance pricing. Review of Accounting Studies 19 (1): 1–42.

Cassell, C.A., L.M. Dreher, and L.A. Myers. (2013). Reviewing the SEC’s review process: 10-K comment letters and the cost of remediation. The Accounting Review 88 (6): 1875–1908.

Chalmers, J.M., L.Y. Dann, and J. Harford. (2002). Managerial opportunism? Evidence from directors’ and officers’ insurance purchases. Journal of Finance 57 (2): 609–636.

Chen, S., X. Chen, Q. Cheng, and T. Shevlin. (2010). Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family firms? Journal of Financial Economics 95 (1): 41–61.

Chen, Z., O.Z. Li, and H. Zou. (2016). Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance and the cost of equity. Journal of Accounting and Economics 61 (1): 100–120.

Chyz, J.A. (2013). Personally tax aggressive executives and corporate tax sheltering. Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (2–3): 311–328.

Chyz, J.A., W.S.C. Leung, O.Z. Li, and O.M. Rui. (2013). Labor unions and tax aggressiveness. Journal of Financial Economics 108 (3): 675–698.

Ciconte, W., M. P. Donohoe, P. Lisowsky, and M. Mayberry. (2016). Predictable uncertainty: The relation between unrecognized tax benefits and future income tax cash outflows. Working Paper.

Core, J.E. (2000). The directors' and officers' insurance premium: An outside assessment of the quality of corporate governance. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 16 (2): 449–477.

De Simone, L., J.R. Robinson, and B. Stomberg. (2014). Distilling the reserve for uncertain tax positions: The revealing case of black liquor. Review of Accounting Studies 19 (1): 456–472.

De Simone, L., L.F. Mills, and B. Stomberg. (2019). Using IRS data to identify income shifting to foreign affiliates. Review of Accounting Studies 24 (2): 694–730.

Dechow, P.M., R.G. Sloan, and A.P. Sweeney. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review 70 (2): 193–225.

Dechow, P.M., W. Ge, C.R. Larson, and R.G. Sloan. (2011). Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemporary Accounting Research 28 (1): 17–82.

Department of Justice. (2005). KPMG to pay $456 million for criminal violations in relation to largest-ever tax shelter fraud case. August 29. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2005/August/05_ag_433.html.

Desai, M.A., and D. Dharmapala. (2006). Corporate tax avoidance and high-powered incentives. Journal of Financial Economics 79 (1): 145–179.

Donelson, D.C., and C.G. Yust. (2019). Insurers and lenders as monitors during securities litigation: Evidence from D&O insurance premiums, interest rates, and litigation costs. Journal of Risk and Insurance 86 (3): 663–696.

Donelson, D. C., B. R. Monsen, and C. G. Yust. (2021). U.S. evidence from D&O insurance on agency costs: Implications for country-specific studies. Journal of Financial Reporting, forthcoming.

Donelson, D.C., J.J. Hopkins, and C.G. Yust. (2015). The role of D&O insurance on securities fraud class action settlements. Journal of Law and Economics 58 (4): 747–778.

Donelson, D.C., J.J. Hopkins, and C.G. Yust. (2018). The cost of disclosure regulation: Evidence from D&O insurance and non-meritorious securities litigation. Review of Accounting Studies 23 (2): 528–588.

Dyreng, S.D., and B.P. Lindsey. (2009). Using financial accounting data to examine the effect of foreign operations located in tax havens and other countries on US multinational firms’ tax rates. Journal of Accounting Research 47 (5): 1283–1316.

Dyreng, S.D., and E.L. Maydew. (2018). Virtual issue on tax research published in the Journal of Accounting Research. Journal of Accounting Research 56 (2): 311–311.

Dyreng, S.D., M. Hanlon, and E.L. Maydew. (2008). Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review 83 (1): 61–82.

Dyreng, S.D., M. Hanlon, and E.L. Maydew. (2019). When does tax avoidance result in tax uncertainty? The Accounting Review 94 (2): 179–203.

Dyreng, S.D., J.L. Hoopes, P. Langetieg, and J.H. Wilde. (2020). Strategic subsidiary disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research 58 (3): 643–692.

Dyreng, S.D., J.L. Hoopes, and J.H. Wilde. (2016). Public pressure and corporate tax behavior. Journal of Accounting Research 54 (1): 147–186.

Erickson, J.M. (2011). Overlitigating corporate fraud: An empirical examination. Iowa Law Review 49: 49–100.

Frank, K.A. (2000). Impact of a confounding variable on a regression coefficient. Sociological Methods & Research 29 (2): 147–194.

Gallemore, J., E.L. Maydew, and J.R. Thornock. (2014). The reputational costs of tax avoidance. Contemporary Accounting Research 31 (4): 1103–1133.

Germaine, C. (2016). Weatherford pays $140M SEC fine over false tax accounting. Law360.com. September 27. Available at: https://www.law360.com/articles/845038/weat Herford-pays-140m-sec-fine-over-false-tax-accounting.

Gillan, S., and C. Panasian. (2015). On lawsuits, corporate governance, and directors’ and officers’ liability insurance. The Journal of Risk and Insurance 82 (4): 793–822.

Goh, B.W., J. Lee, C.Y. Lim, and T. Shevlin. (2016). The effect of corporate tax avoidance on the cost of equity. The Accounting Review 91 (6): 1647–1670.

Graham, J.R., and A.L. Tucker. (2006). Tax shelters and corporate debt policy. Journal of Financial Economics 81 (3): 563–594.

Griffith, S.J. (2006). Uncovering a gatekeeper: Why the SEC should mandate disclosure of details concerning directors' and officers' liability insurance policies. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 154 (5): 1147–1208.

Guenther, D.A., S.R. Matsunaga, and B. Williams. (2017). Is tax avoidance associated with firm risk? The Accounting Review 92 (1): 115–136.

Guenther, D.A., R.J. Wilson, and K. Wu. (2019). Tax uncertainty and incremental tax avoidance. The Accounting Review 94 (2): 229–247.

Gupta, M., and P. Prakash. (2012). Information embedded in directors and officers insurance purchases. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice 37: 429–451.

Hanlon, M., and S. Heitzman. (2010). A review of tax research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2–3): 127–178.

Hanlon, M., E.L. Maydew, and D. Saavedra. (2017). The taxman cometh: Does tax uncertainty affect corporate cash holdings? Review of Accounting Studies 22 (3): 1198–1228.

Hanlon, M., S. Rajgopal, and T. Shevlin. (2003). Are executive stock options associated with future earnings? Journal of Accounting and Economics 36 (1–3): 3–43.

Hasan, I., C.K.S. Hoi, Q. Wu, and H. Zhang. (2014). Beauty is in the eye of the beholder: The effect of corporate tax avoidance on the cost of bank loans. Journal of Financial Economics 113 (1): 109–130.

Heitzman, S.M., and M. Ogneva. (2019). Industry tax planning and stock returns. The Accounting Review 94 (5): 219–246.

Holderness, C.G. (1990). Liability insurers as corporate monitors. International Review of Law and Economics 10 (2): 115–129.

Huskins, P. C. (2019). 6 ways to reduce your D&O insurance premiums. Woodruff Sawyer. April 3. Available at: https://woodruffsawyer.com/do-notebook/6-ways-to-reduce-do-insurance-premiums/.

Hutchens, M., and S. O. Rego. (2015). Does greater tax risk lead to increased firm risk? Working Paper.

Hutchens, M., S. O. Rego, and B. Williams. (2019). Tax avoidance, uncertainty, and firm risk. Working Paper.

Kean, F. (2013). What is a D&O insurers’ appetite for settling unpaid corporate taxes? Willis Towers Watson Wire. October 21. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20140815195744/https://blog.willis.com/2013/10/what-is-a-do-insurers-appetite-for-settling-unpaid-corporate-taxes/.

Kim, I., and D.J. Skinner. (2012). Measuring securities litigation risk. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53 (1): 290–310.

LaCroix, K. M. (2011). Guest post: New IRS form could spawn new waves of shareholder suits. D&O Diary.com. March 22. Available at: https://www.dandodiary.com/2011/03/articles/securities-litigation/guest-post-new-irs-form-could-spawn-new-waves-of-shareholder-suits/.

Larcker, D.F., and T.O. Rusticus. (2010). On the use of instrumental variables in accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 49 (3): 186–205.

Law, K., and L. F. Mills. (2019). Taxes and haven activities: Evidence from linguistic cues. Working Paper.

Lennox, C., P. Lisowsky, and J. Pitman. 2013. Tax aggressiveness and accounting fraud. Journal of Accounting Research 51 (4): 739–778.

Leone, A.J., M. Minutti-Meza, and C.E. Wasley. (2019). Influential observations and inference in accounting research. The Accounting Review 94 (6): 337–364.

Lin, C., M.S. Officer, and H. Zou. (2011). Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance and acquisition outcomes. Journal of Financial Economics 102 (3): 507–525.

Lipman, M. (2017). Tougher tax evasion laws mean more D&O risks for insurers. Law360.com. June 2. Available at: https://www.law360.com/subscribe/email_verification ?article_id=930783§ion=financial-services-Uk.

Lisowsky, P., L. Robinson, and A. Schmidt. (2013). Do publicly disclosed tax reserves tell us about privately disclosed tax shelter activity? Journal of Accounting Research 51 (3): 583–629.

Luo, Y., and V. Krivogorsky. (2017). The materiality of directors’ and officers’ insurance information: Case for disclosure. Research in Accounting Regulation 29: 69–74.

Markle, K.S., and D.A. Shackelford. (2012). Cross-country comparisons of corporate income tax. National Tax Journal 65 (3): 493–528.

Marsh and McLennan. (2017). Evolving directors & officers liability environment: Emerging issues & considerations. August 29. Available at: http://boardleadership.nacdonline.org/rs/815-YTL-682/images/NACD-MMC%20Evolving%20Directors%20%26%20Officers%20Liability%20Environment%208.29.17.pdf.

Matthews, R. G., and J. Whalen. (2006). Glaxo to settle tax dispute with IRS over U.S. unit for $3.4 billion. Wall Street Journal. September 12. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB115798715531459461.

Metzger, C, and B. Mekherjee. (2015). When the government comes knocking: Maximizing insurance coverage for government investigations. December. Available at: https://store.legal.thomsonreuters.com/law-products/news-views/corporate-counsel/when-the-government-comes-knocking-maximizing-insurance-coverage-for-government-investigations.

NERA. (2018). Recent trends in securities class action litigation: 2017 full-year review. NERA Economic Consulting. Available at: http://www.nera.com/content/dam/nera/public ations/2018/PUB_Year_End_Trends_Report_0118_final.Pdf.

Neuman, S.S., T.C. Omer, and A.P. Schmidt. (2020). Assessing tax risk: Practitioner perspectives. Contemporary Accounting Research 37 (3): 1788–1827.

O’Brien, J.M., and M.A. Oates. (2000). Transfer pricing controversies. Global Transfer Pricing 2000 (February/March): 7–9.

O’Connell, P. (2014). D&O market update: Effects from the Halliburton ruling. Advisen. August 7. Available at: https://www.advisenltd.com/2014/08/07/market-update-effects-halliburton-ruling/.

O’Sullivan, N. (1997). Insuring the agents: The role of directors’ and officers’ insurance in corporate governance. Journal of Risk and Insurance 64 (3): 545–556.

Pickhardt, W. A. (2006). Legal opinions addressing uncertain tax positions may be desirable under new FASB rules. Faegre Baker Daniels. November 26. Available at: https://www.faegrebd.com/legal-opinions-addressing-uncertain-tax-positions-may-be-desirable-under.

Powell, L. (2013). Decline in securities class action filings in 2012: What it doesn’t mean. D&O Disclosure. January 27. Available at: https://www.dandodiscourse.com/2013/01/27 /decline-in-securities-class-action-filings-in-2012-what-it-doesnt-mean-2/.

Rego, S.O., and R.J. Wilson. (2012). Equity risk incentives and corporate tax aggressiveness. Journal of Accounting Research 50 (3): 775–810.

Sadler & Company. (2019). D&O liability insurance claims procedure. Available at: https://www.sadlersports.com/common/claims-do.php.

Seelye, K. Q., and J. Barron. (2007). Wall street journal wins two Pulitzer prizes. New York Times. April 17. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/16/business/media/16cnd-pulitzer.html.

Shackelford, D.A., and T. Shevlin. (2001). Empirical tax research in accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31: 321–387.

Shevlin, T. J., O. Urcan, and F. P. Vasvari. (2013). Corporate tax avoidance and public debt costs. Working Paper.

Tax Foundation. (2014). How much lower are Canada’s business taxes? August 26. Available at: https://taxfoundation.org/how-much-lower-are-canadas-business-taxes/.

Towers Watson. (2013). Directors’ and officers’ liability survey: 2012 summary of results. Towers Watson. Available at: https://www.towerswatson.com/en-US/Insights/IC-Types/Survey-Research-Results/2013/03/Directors-and-Officers-Liability-2012-Survey-of-Insurance-Purchasing-Trends.

Towery, E.M. (2017). Unintended consequences of linking tax return disclosures to financial reporting for income taxes: Evidence from schedule UTP. The Accounting Review 92 (5): 201–226.

Tyukody, D. J., and M. Spindler. (2008). The next wave of securities litigation: FIN 48. Law360.com. November 18. Available at: https://www.law360.com/articles/77352/the-next-wave-of-securities-litigation-fin-48.

Vinson & Elkins. (2018). Current trends in directors and officers liability insurance. December 20. Available at: https://www.velaw.com/insights/current-trends-in-directors-and-officers-liability-insurance/.

Wilde, J.H., and R.J. Wilson. (2018). Perspectives on corporate tax avoidance: Observations from the past decade. Journal of the American Taxation Association 40 (2): 63–81.

Wilson, R.J. (2009). An examination of corporate tax shelter participants. The Accounting Review 84 (3): 969–999.

Zeng, T. (2017). Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance and aggressive tax-reporting activities: Evidence from Canada. Accounting Perspectives 16 (4): 345–369.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Blouin (editor), an anonymous referee, Anwer Ahmed, Mark Anderson, Brad Hepfer, Antonis Kartapanis, Dan Lynch, Sean McGuire, Carl Metzger, Lauren Milbach, Lillian Mills, Stevie Neuman, Adrienne Rhodes, John Robinson, Ed Swanson, David Tabak, Connie Weaver, Brady Williams, Nina Xu, the Texas A&M Tax Readings Group, 2017 AAA annual meeting conference participants, and Texas A&M workshop participants for helpful comments. We thank Michelle Hanlon, Ryan Wilson, John Gallemore, Jake Thornock and Edward Maydew for sharing tax shelter data; Kelvin Law and Lillian Mills for sharing their outbound tax haven data; and Scott Dyreng for sharing his Exhibit 21 data. The paper was previously titled, “Trends in tax-related litigation and D&O insurance pricing: Did increased tax risk affect litigation costs?” and “Is tax planning associated with tax risk? Evidence from D&O insurance.” We gratefully acknowledge research support provided by the Red McCombs School of Business and the Mays Business School. All errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Tax-Related Litigation – Collection Procedure and Case Examples

This appendix provides details of our collection procedure and examples of and excerpts from tax-related derivative, securities class action, and SEC litigation related to explicit taxes, tax reporting, or other issues.

1.1 Collection procedure

To identify tax-related cases, we begin with all litigation in Advisen’s database (see Section 4 for more details on the data source) that includes the word “tax” in the case description. We read each case description (and the case docket where necessary) to ensure all cases contain tax-related allegations. This is critical because cases often mention “tax” when describing firm income or performance but do not actually allege tax-related issues (e.g., one case states, “the Company previously incurred a pretax charge…”, but we exclude this case because it does not involve tax-related allegations). Once we identify our final sample, we read each case docket to identify the allegations in the case. Using the primary allegation(s) in each case, we then classify each case into one of three buckets: 1) where tax is the primary allegation, 2) where the tax allegation is as important as other allegations, or 3) tax is a secondary allegation. We then classify each case based upon whether the underlying tax activity that triggered the case was 1) explicit tax focused, 2) tax reporting focused, 3) both explicit tax and tax-reporting focused, or 4) other (e.g., shareholder objections to proposed merger and acquisitions). Finally, we read the case docket and use Factiva news searches, if needed, to determine the triggering event for each case.

1.2 Explicit tax-related issues

1.2.1

Shuffle Master Inc.

Footnote 43

In securities class action litigation filed in 2007 against Shuffle Master Inc., shareholders alleged that the firm and certain of its officers misrepresented the firm’s financial results by fraudulently booking intercompany transactions stemming from the firm’s tax avoidance strategy. Specifically, the complaint alleges: “The fraudulent booking of intercompany transactions arose out of Shuffle Master’s tax avoidance scheme, whereby the Company transferred profits that were otherwise taxable in the U.S., to foreign countries where such profits would be taxed at a much lower rate, if at all. This transfer was accomplished by Shuffle Master’s parent company in Las Vegas engaging in, inter alia, intercompany “purchases” from an Austrian subsidiary.” In early 2007, the firm issued a press release admitting that it incorrectly accounted for the intercompany transaction and would restate its financial statements. In response to this news, the firm’s stock fell approximately 8%.

1.2.2

Wells Fargo & Co.

Footnote 44

In January 2010, shareholders and other investors filed a derivative suit against Wells Fargo & Co. and its managers for breach of fiduciary duty, abuse of control, and gross mismanagement relating to the firm’s use of “sale-in/lease-out” (SILO) tax shelters. According to the claim, Wells Fargo “purchased” rail cars or buses from public transit agencies and leased the assets back to the agencies, subsequently claiming deductions for the rail cars or buses on its corporate franchise returns. However, the transactions lacked economic substance and were solely for tax benefits, as no property physically changed hands. Plaintiffs claimed that the firm’s managers breached their fiduciary duties to shareholders by authorizing the firm’s use of the SILO shelters and failing to settle with the IRS during an amnesty period. Specifically, the claim asserted that “defendants knew or should have known since at least 1996, that the IRS considered the types of leveraged lease transactions at issue here to be dubious tax shelters … Defendants should have known that the SILO Transactions and Wells Fargo’s attempt to file tax deductions for them were violations of IRS regulations, but took no steps in a good faith effort to prevent or remedy the situation. Instead, Defendants approved or ratified conduct by Wells Fargo which was not in the best interest of the Company or shareholders …” This included investing $1.6 billion in SILO-related assets despite IRS audits that disallowed $162 million in deductions and assessed the firm a $8 million fine.

1.3 Tax reporting issues

1.3.1 Weatherford International Ltd.

SEC Litigation.Footnote 45

In September 2016, oil and gas services company Weatherford International paid the SEC $140 million to settle charges that it had inflated its earnings by over $900 million by fraudulently manipulating its income tax accounting. Specifically, the SEC alleged that between 2007 and 2010, James Hudgins, Weatherford’s vice president of tax and later an officer of the firm, and Darryl Kitay, a tax manager and later a senior tax manager who worked under Hudgins, “…made numerous post-closing adjustments or ‘plugs’ to fill gaps to meet ETRs that Weatherford previously disclosed to analysts and the public.” This accounting scheme materially understated Weatherford’s ETR and tax expense, thereby materially inflating the firm’s earnings. According to the SEC, over the course of this fraud, “Weatherford regularly touted its favorable ETR to analysts and investors as one of its key competitive advantages, which it attributed to a superior international tax avoidance structure ...” In addition, the SEC found that Weatherford did not have sufficient internal accounting controls to identify and properly account for its accounting of income taxes throughout this period. Consequently, Weatherford restated its financial statements three times over the course of 18 months.

Securities Class Action Litigation.Footnote 46

In 2012, shareholders of Weatherford brought a securities class action lawsuit against the firm and certain of its directors and officers for issuing several materially false and misleading statements, thereby violating Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5. According to the claim, in March 2011, Weatherford announced a restatement of $500 million stemming from an accounting for income tax fraud occurring at the firm between 2007 and 2010. Shortly after this announcement, Weatherford responded to an SEC inquiry about the restatement by writing that “we believe that our public disclosures have been corrected for the relevant full-year periods.” However, in February and July 2012, Weatherford announced its second and third restatements, this time for $256 million and $186 million, respectively. The claim alleges that the firm and its officers and directors knew or recklessly failed to inform investors that its first restatement was incorrect and hastily filed this restatement to “give the market the impression that it remedied its material weakness in internal controls over financial reporting of income taxes.” Shareholders suffered a loss in value as a result of these announcements, as the value of the firm’s stock declined approximately 34% over this period. The claim was settled in 2015 for $120 million.

1.4 Both explicit tax-related and tax reporting issues

1.4.1

Pall Corporation.

Footnote 47

In 2007, shareholders of Pall Corporation brought a securities class action lawsuit against the firm and certain of its officers and directors for violating securities laws by misrepresenting the firm’s ETR in the financial statements. The claim alleges that throughout the class period, “the Company’s press releases and quarterly and annual reports filed with the SEC were each materially false and misleading because Pall was overstating its reported financial results by materially understating its income tax liability.” Specifically, the firm’s ETR reported in its financial statements and press releases was incorrect because it was based on a cash ETR figure that failed to take into account that one of the firm’s intercompany transactions gave rise to deemed dividend income under Internal Revenue Code §956. As a result, the firm owed the IRS in excess of $130 million in unpaid taxes, exclusive of interest and penalties. In issuing a press release announcing the error and need to restate its financial statements, the firm explained said the following.

The amount of the understatement has not yet been finally determined, but is material and relates to the taxation of certain intercompany payable balances that mainly resulted from sales of products by a foreign subsidiary of the Company to a U.S. subsidiary of the Company. Under the Internal Revenue Code, these unpaid balances may have given rise to deemed dividend income to the Company that was not properly taken into account in the Company’s U.S. income tax return and provision for income taxes…The Company’s tax liability will include the amount of taxes that would have been payable with respect to any deemed dividend income in the affected periods, as well as interest on overdue amounts of taxes payable and penalties that may be assessed by the Internal Revenue Service on the eventual resolution of this matter.

1.5 Other issues

1.5.1

Johnson Controls Inc.

Footnote 48

In 2016, shareholders and employees of Johnson Controls Inc. filed a securities class action complaint against the firm and certain of its senior executive officers and directors for breaching their fiduciary duties by structuring a tax inversion transaction such that capital gains taxes unjustly fell on the shareholders. The complaint alleges that the firm entered into a tax inversion agreement with Tyco, an Irish-domiciled company, and structured the inversion to help the firm obtain favorable tax treatment by avoiding U.S. income taxes. In a tax inversion, a U.S. domiciled target corporation becomes a subsidiary of a foreign domiciled parent corporation. As a result, shareholders of the U.S. corporation essentially exchange their stock for stock in the foreign parent, thereby becoming shareholders of the foreign corporation. The plaintiffs argue that, to avoid the anti-inversion provisions of Internal Revenue Code, §4985 and §7874 (e.g., a 15% excise tax levied on directors’ and senior executives’ stock compensation), the defendants strategically conditioned the inversion on Johnson Control shareholders owning less than 60% of the combined entity. This, in turn, resulted in the shareholders of Johnson Control owing capital gains taxes under Internal Revenue Code §367(a).

Appendix 2 Variable Definitions

Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

BOARDSIZE | The total number of directors on the board of directors, as reported by Boardex. |

CAPINT | Capital intensity, measured as net property, plant, and equipment (PPENT) divided by lagged total assets (AT). |

DACC | Absolute value of discretionary accruals calculated following the modified-Jones discretionary accruals model (Dechow et al. 1995). |

DELTA | Dollar change of the CEO’s portfolio value for a 1% change in firm stock price (in thousands). |

EQINC | Equity income in earnings (ESUB) divided by lagged total assets (AT). |

FI | Foreign income (PIFO) divided by lagged total assets (AT). |

FSCORE | The financial statement manipulation risk score, computed following Dechow et al. (2011). |

GOV_MISSING | Separate indicator variables equal to 1 if any of the following variables are missing: BOARDSIZE, DELTA, PCTIND, and VEGA and zero otherwise. |

HAVENWITH | An indicator equal to one if the firm has outbound payments to a tax haven where the firm mentions physical presence in a given year, as computed by Law and Mills (2019), and zero otherwise. |

HAVENWITHOUT | An indicator equal to one if the firm has outbound payments to a tax haven where the firm mentions no physical presence in a given year, as computed by Law and Mills (2019), and zero otherwise. |

INTANG | Intangible assets (INTAN) divided by lagged total assets (AT). |

LEV | Long-term debt (DLTT) divided by lagged total assets (AT). |

LITRISK | Litigation risk, calculated using coefficients in model 3 of Table 7 of Kim and Skinner (2012). |

M&A | An indicator variable equal to one if the firm has nonzero acquisitions or mergers (AQP) in a given year and zero otherwise. |

MTB | Market-to-book ratio at the beginning of the year, defined as market value of equity (CSHO * PRCC_F) divided by book value of equity (CEQ). |

NOL | An indicator variable set equal to one if a firm has a positive loss carry forward (TLCF) at the beginning of the year and zero otherwise. |

ΔNOL | The change in the loss carry forward (TLCF) divided by lagged total assets (AT). |

NONTAXSETTLE | The natural logarithm of one plus total settlements (in millions) of nontax litigation cases paid in the current year. Nontax litigation is all litigation (not in the tax-related litigation sample) that are either 1) SEC accounting cases alleging a Rule 10b-5 violation, 2) securities class actions alleging a Rule 10b-5 violation, or 3) derivative cases. We exclude initial public offering (IPO) allocation, mutual fund, and analyst cases (Kim and Skinner 2012). |

PCTIND | Percentage of independent directors on the board of directors, as reported in Boardex. If a firm is missing this data, we set it equal to zero and set GOV_MISSING equal to one. |

PREM_LIMIT | The natural logarithm of one plus the total D&O insurance premium paid scaled by the total D&O coverage limit for all of the firm’s D&O policies during the fiscal year. |

RD | Research and development expenses (XRD) scaled by lagged total assets (AT). |

RESTATE | An indicator variable equal to one if the firm announces a restatement via a Form 8-K Item 4.02 nonreliance restatement or in a correction in the next required filing in accordance with SAB Topic 108 and zero otherwise. |

RET | The excess of the buy-and-hold stock return for the fiscal year over the market return for the same period. |

RETVOL | The standard deviation of the firm’s monthly returns over the 12-month period ending with the firm’s fiscal year-end. |

ROA | Return on assets, defined as pretax income (PI) divided by lagged total assets (AT). |

SETTLE | The decrease in UTBs due to settlements with the IRS, calculated as UTB settlements (TXTUBSETTLE), scaled by the ending balance of UTBs (TXTUBEND). |

SGA | Selling, general, and administrative expenses (XSGA) scaled by lagged total assets (AT). |

SIZE | The natural logarithm of assets in millions (AT) at the end of the fiscal year. |

TA_CASH | Industry-size-adjusted cash ETR, computed as the firm’s mean industry-size-cash ETR less the firm’s cash ETR. Cash ETR is computed as the sum of cash taxes paid (TXPD) for years t, t-1, and t-2 divided by the sum of pre-tax income (PI) for years t, t-1, and t-2. Rankings of size are done independently of industry classification. |

TA_FACTOR | The first factor obtained using principal components analysis on TA_CASH, TA_GAAP, UTB, and SETTLE. |

TA_GAAP | Industry-size-adjusted GAAP ETR, computed as the firm’s mean industry-size-GAAP ETR less the firm’s GAAP ETR. GAAP ETR is calculated as the sum of current tax expense (TXT) for years t, t-1, and t-2, divided by the sum of pre-tax income (PI) for years t, t-1, and t-2. Rankings of size are done independently of industry classification. |

TAX | Measures of tax aggressiveness used in our analyses, including TA_CASH, TA_GAAP, UTB, and SETTLE. |

UTB | Unrecognized tax benefits, measured as TXTUBEND at the end of the year scaled by lagged total assets (AT). |

VEGA | Dollar change of the CEO’s portfolio value for a 1% change in return volatility (in thousands). |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Donelson, D.C., Glenn, J.L. & Yust, C.G. Is tax aggressiveness associated with tax litigation risk? Evidence from D&O Insurance. Rev Account Stud 27, 519–569 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09612-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09612-w