Abstract

Introduction

Self-report is the gold standard for measuring children’s health-related outcomes. Design of such measures is complex and challenging. This review aims to systematically appraise the evidence on recall period, response scale format, mode of administration and approaches needed to enable children and young people < 19 years to participate in valid and reliable self-reporting of their health outcomes.

Method

PsycInfo, Medline, CINAHL and Embase were searched from 1 January 1990 to 15 March 2020, and citation searching undertaken in Scopus. Articles were included if they were primary research or case reports of ≥ 3 participants reporting the following: recall period, response scale selection, administration modality. Quality was assessed using QualSyst, and results synthesised narratively. This review was conducted and reported according to PRISMA guidelines.

Results

81 of 13,215 retrieved articles met the inclusion criteria. Children < 5 years old cannot validly and reliably self-report health outcomes. Face scales demonstrate better psychometric properties than visual analogue or Likert scales. Computerised and paper scales generally show equivalent construct validity. Children prefer computerised measures. Children ≤ 7 years old think dichotomously so need two response options. Those > 8 years old can reliably use a 3-point scale.

Conclusion

The results of this review have both clinical and research implications. They can be used to inform appropriate choice of PROM for use with CYP in the clinical setting. We also give eight recommendations for future development of self-reported outcome measures for children and young people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are validated questionnaires that are completed by patients to ascertain perceptions of their health status and well-being [1, 2]. PROMs range from single-item symptom ratings e.g., pain scales, to complex multidimensional tools measuring health-related quality of life [3]. PROMs are considered to be the gold standard for measuring subjective experiences, because the information comes directly from the patient [4]. When collecting data on the health-related outcomes of children and young people (CYP) it is good practice to enable CYP to self-report whenever possible.

The design and implementation of PROMs for CYP presents methodological complexities, including consideration of response format, recall period and the mode of administration [5, 6]. These considerations should be addressed at the design stage to ensure PROMS are both feasible (ability to complete a measure) and acceptable (willingness to complete a measure) [7]. Acceptable modes of administration are crucial to enable CYP to engage and provide valid and reliable results [8].

Careful consideration of recall period, response scale format and administration modality during all stages of PROM design may increase response and completion rates, whilst maintaining and enhancing validity and reliability. The aim of this review is to systematically appraise the evidence on response scale type, recall period, administration modality and approaches to enable CYP < 19 years to participate in valid and reliable self-reporting of their health outcomes.

Methods

This systematic literature review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [9], and registered on PROSPERO (CRD42019135264).

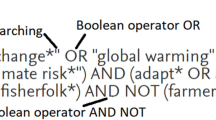

PsycINFO, Medline, CINAHL and Embase were searched from 1st January 1980 (i.e., when outcome measurement in children began to be reported in the scientific literature [10,11,12]) to 15th March 2020. The search combined terms for children used in a previous systematic review [13] with those for different response scale formats, recall periods and methods of administration ( \* MERGEFORMAT Table 1 Search terms). Additional articles were searched using ‘cited by’ (Scopus), forwards and backwards referencing and consulting other experts in the field. The full Medline search strategy is reported in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) study population CYP ≤ 18 years old (studies reporting participants ≥ 19 years old were included if data were presented separately). Our original protocol planned to include those ≤ 17 years old but a large proportion of identified papers included 18 year olds so this was amended; (2) primary research of self-report of health outcomes among CYP; (3) studies evaluating recall period, response format, administration modality or approaches to engage CYP in self-reporting health outcomes in terms of their effect on measurement properties (validity, reliability and responsiveness) [7], acceptability (willingness to use a particular response format, administration mode or recall period), feasibility of use (ability to use a particular response format, administration mode or recall period) or preference for a particular mode, response format or recall period [7]; (4) written in the English language.

Exclusion criteria were case reports of < 3 participants (due to the risk of selection bias), discussion articles, editorials, reports, letters and reviews.

Study selection and data extraction

Citations were imported to EndNote (v9) and de-duplicated. Titles and abstracts of retrieved articles were screened for eligibility by one reviewer (LC). If there was not enough information within the title and abstract to determine eligibility, the full text article was screened. Remaining full text articles were screened by LC. 10% of the full text articles were screened by a 2nd reviewer (JA). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer consulted as necessary (CES or RH).

Data from eligible studies were extracted into a common table: study authors, year of publication, geographic location, objective, study design, sample characteristics (population, size, setting), measure characteristics reported (recall period, response format, administration modality) and main findings.

Quality appraisal and data synthesis

QualSyst was applied rather than the COSMIN checklist in line with the overall aim of this review to examine response format, administration mode and recall period, rather than to appraise specific PROMs [14]. QualSyst assesses study quality with two scoring systems, one for qualitative and one for quantitative research. The qualitative scale consists of ten items with scores from zero to two, yielding a maximum score of 20. The quantitative scale consists of 14 items with scores from zero to two, an option to score an item ‘not applicable’, and maximum total score of 28. Overall scores are reported as percentages. Mixed method studies received two scores—one each for the qualitative and quantitative components [15]. Inter-rater agreement was assessed for 10% of the included articles.

Results were synthesized narratively to appraise the heterogeneity of included studies, and any similarities or differences in findings. The results were used to make recommendations on recall period, response format and administration mode when developing self-reported health outcome measures for CYP.

Results

Study selection

The search identified 13,207 articles after deduplication. A further 8 were identified via reference searching. 187 articles required full text review and 81 met the inclusion criteria. Of the articles included, 45 reported on response format [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60], seven on recall period [61,62,63,64,65,66,67], 24 on administration mode [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91], four on both recall and response format [92,93,94,95] and one on response format and administration mode [96]. The PRISMA flowchart is shown in Fig. 1 [9].

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process [9]

General Information on Included Studies

Tables 2, 3 and 4 summarise included studies and quality scores. Supplements 2 and 3 provide details of quality scores by item. The majority of included studies were conducted in Europe (n = 25/81) [17,18,19,20, 22, 26, 34, 37, 40, 41, 44, 50, 59, 65, 69, 71, 72, 75,76,77,78, 82,83,84, 87], the USA (n = 31/81) [16, 28, 29, 36, 38, 46,47,48, 51, 53, 54, 57, 58, 61,62,63,64, 66,67,68, 70, 74, 79, 80, 85, 86, 89, 90, 92, 95, 96] and Canada (n = 18/81) [21, 23,24,25, 27, 32, 39, 42, 43, 49, 52, 55, 56, 60, 81, 88, 91, 93] with two from Australia [31, 33], and one each from Japan [45], Korea [35], New Zealand [73], Kenya [94] and Jordan [30]. With respect to study design, n = 68/81 used quantitative methodology, n = 11/81 qualitative methodology and n = 2/81 mixed methods. Settings were predominantly home, school/nursery or hospital, and the 33,834 participants ranged from 3 to 18 years and were either healthy children (n = 30) or had one of a wide range of medical conditions (n = 50).

Quality of included studies

Study quality ranged from 38 to 96%, with 10/81 scoring less than the 55% quality inclusion threshold recommended by the QualSyst [15]. The main reasons for poor scoring were small sample size, using parametric statistical tests without stating whether data was normally distributed, treating data from Likert scales as if it was interval, using Pearson’s correlation coefficient instead of intraclass correlation coefficient [97] and not stating randomisation methods. Qualitative papers rarely discussed reflexivity, the role of the researcher in the interview process or the connection to a theoretical framework. These low scoring studies were included in the review as it is often difficult to determine whether quality scoring elements were not reported rather than not taken into consideration.

Response format

50 papers investigated ability to use specific response formats [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60, 92,93,94,95,96] (see Table 2 for details). The majority reported on one or more of the following pictorial scales, (faces pain scale revised (FPS-R) or Wong-Baker faces) (n = 24), visual analogue scales (VAS) (n = 15), and Likert scales (numerical or word descriptor) (n = 14). The methodology for these studies was mainly quantitative, assessing acceptability, feasibility, validity and reliability. Nine qualitative studies used cognitive interviews to assess children’s understanding of response formats.

One study demonstrated that 3-year-olds exhibited a ‘yes’ bias to knowledge and preference-based questions even though they knew the answer should be ‘no’. By the age of 5–6 years this response bias did not exist in preference-based questions and was only weakly associated with knowledge questions regarding familiar objects [45].

Pictorial scales (n = 24 studies)

Most pictorial scales for children are ‘faces’ scales. These are generally used for self-reporting pain and show a series of faces with graded intensity from ‘no pain’ to ‘worst pain possible’ [24]. Children are asked to point to the face that best shows how they are feeling. Most studies in this review have used either the Wong-Baker Faces scale (n = 5) or the FPS-R (n-19). The Wong-Baker scale has six cartoon-like, hand drawn faces ranging from smiling to crying with a score of 0–5 [98]. The FPS-R was adapted from the original FPS which had seven faces [99]. The FPS-R excludes smiles and tears and has six hand-drawn faces rather than seven so that it can be scored from 0 to 5 allowing scoring to be in line with other pain measures [32]. There is also a simplified version of the FPS (S-FPS), designed for children 3–5 years old, which first asks the child if they are in pain and if they respond ‘yes’ then they are shown a three-point faces scale [27].

From the age of seven, the use of six-point faces scales shows construct (convergent and discriminant) validity [16, 41, 49, 56, 96]. Convergent validity was found with numerical/verbal rating scales, VAS and the Poker Chip Tool in children 6–8 years old (r > 0.7 or p < 0.001) [22]). The Poker Chip (known as Pieces of Hurt) tool involves children being asked to pick the number of Poker Chips that represent their level of pain. One chip represents a small amount of pain and four the most amount.

Cognitive interview studies showed that children of 7 and over are generally able to understand and complete faces measures [96]. In younger children, the evidence on ability to use faces scales is mixed. Two studies report that six-point faces scales are valid (convergent validity r > 0.71 with word descriptor scale; discriminant validity p < 0.001 before and after a painful procedure) and reliable (test–retest reliability r = 0.9, p < 0.005) in children as young as three. These studies had relatively low quality scores and data on 3–7-year olds was analysed together [36, 57]. Other studies have shown that not all children under 7 years are able to understand six-point faces scales, and some have difficulty in using the middle of the scale [33, 49, 93, 96]. There is no evidence that ability to use faces scales differs between healthy children and those with underlying conditions.

Although faces scales tended to demonstrate convergent validity with other response formats such as VAS and the Poker Chip tool in children between 4 and 7 years, scores tend to be skewed low, suggesting children are scoring at the extremes and are unable to use the middle response option [31]. Studies of the S-FPS suggest that from 4 years, a three-point faces scale can be used reliably, although 4-year-olds tend to use the scale anchors thus rendering it dichotomous [26, 27].

Scales with smiling anchors lead to reporting of higher pain scores in 5–13-year-olds, compared to those with neutral face anchors, although scores between the two scales correlate [23,24,25]. Children aged 5–12 years expressed a preference for cartoon like faces in one study [24].

Likert scales (n = 14 studies)

These studies were carried out with children 8 years and over, except one which had a lower age limit of 6 years [59]. Most showed that children from 8 years old can understand and use a 4 or 5-point Likert scale [20, 34, 42, 43, 46, 95], with scores correlating strongly with a VAS [59]. Cognitive interview studies (5–18 years) demonstrated that if children struggled with Likert scales, it was usually with the middle points of a scale [34, 42, 92] with the term ‘moderate’ being perceived as confusing [44, 46]. One study found that children 13–18 years old could not use a 4-point Likert scale as they were unable to quantify the differences between response options. Addition of a fifth point created more divergence and was harder to understand [94]. Four studies in children 8–18 years used item response theory to examine scale performance [17, 38, 53, 60]. Three found that using a five-point scale led to disordered thresholds and performance was enhanced by using a three-point scale [17, 38, 60]. One study in 9–10-year-olds showed that a five-point scale was not fully utilised [53]. Negatively formulated questions were shown to have no effect on reliability in one study [20]. As with faces scales, there is no evidence that ability to use a Likert scale differs between healthy and unwell children.

Visual analogue scales (n = 15 studies)

A visual analogue scale is usually a 100 mm long horizontal line with verbal descriptors at each end expressing extremes of feeling. Respondents mark a point on the line that best corresponds to the severity of their symptom or feeling [100].

At all ages the VAS seems to be less valid and reliable to use than faces or Likert scales, with slight pain on a verbal rating scale corresponding to a wide interval of 7–65 on a VAS scale [18, 57]. In children aged 5–7 years, cognitive ability, chronological age and the ability to conduct a seriation task (arranging circles in order of size) seems to be the best predictor of ability to use a VAS [47, 48]. Cognitive ability was less important after the age of seven [48]. This finding is supported by a study in children 9–12 years with learning impairment who only used the scale anchors, whereas children without learning impairment of the same age were able to use the whole VAS [21]. One study suggests that for those over 8 years old, the addition of pictorial anchors allowed children to make greater use of the full scale [29].

Other scales (n = 6)

The Pain Block Scale is a pictorial ordered block scale with a score between 0 and 10. This demonstrates agreement with the FPS-R and has discriminant validity in children from the age of 4–7 years who can count to five [35].

Two studies in children 3–14 years showed that the Poker Chip tool has convergent validity with faces scales (r = 0.67; p < 0.001) [30, 54] and one in children 4–7 years old showed convergent validity with VAS and VRS (r = 0.7) [31]. One study showed that 65% of 4–7-year olds understood the scale [93].

The coloured analogue scale (CAS) resembles a ruler, with one side showing a wedge-shaped figure filled with colour that progresses from white to red as the figure widens. The other side shows corresponding numerical ratings from 1 to 10 cm. One study demonstrated discriminant and construct validity with the VAS, and children from 5 to 16 years found the CAS easier to use than the VAS [55].

Preference of scale (n = 13)

13 studies asked children 3–18 years their preference of scale [18, 22, 30, 36, 41, 44, 50, 51, 54,55,56, 59]. In all studies using a faces scale this was preferred to VAS and Likert scales [22, 30, 36, 41, 54, 56, 57]. In all but one study, Likert scales were preferred to VAS [36, 50, 51, 59]. Four studies examined preference for the CAS, and in three it was preferred to FPS-R, VAS and Likert scales [22, 51, 55]. The FPS-R was preferred to the CAS in one study [41].

Recall period (n = 11)

11 studies reported on recall period [61,62,63,64,65,66,67, 92,93,94,95] (see Table 3 for details). Of these, 5/9 compared daily diary reports to retrospective questionnaires. Four of these were conducted in children 8 years and over and one in children from 6 years old. They showed that shorter recall periods lead to better correlation with daily diaries, with 7–14 days being optimal [61,62,63,64,65]. The other six studies were cognitive interview studies. These suggest that children under 8 years old cannot understand the concept of a week [92] and some could not understand the term ‘yesterday’ [93]. Those over 8 years could use both 7 day and 4-week recall periods [66, 67, 92, 95]. One study asked children 13–18 years old their recall preference and they suggested that 24 h was preferable but that one month would be easy to remember as they had monthly clinic appointments [94].

Administration mode (n = 24)

24 studies reported on administration mode with children aged 4–18 years [68, 70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91, 96] (see Table 4). The majority compared paper and pencil PROMs with an identical computerised version. Most studies showed moderate to strong correlation between paper and computerised versions [71, 75, 76, 81, 83, 84, 87,88,89, 91]. All studies that asked preference for mode showed preference for computer-based measures [71,72,73, 78, 81, 87, 91]. Sensitive subjects such as stress, coping, alcohol and tobacco use were more likely to be reported using web-based measures in children 8–18 years [70, 74, 78, 79]. One study showed that those under 8 years needed help completing a computerised measure [96]. There was fewer missing data with computerised measures. It was not always clear whether this was due to the inability to move on until a question was completed [75, 82, 85]. Strong factorial invariance was found across telephone, face to face and mail [86], and computer and telephone methods were also shown to be strongly correlated [90].

Discussion

This review provides evidence that CYP over 5 years old can meaningfully report on aspects of their own health, providing consideration is given to age, response format and recall period. CYP as young as 4 years old expressed a preference for completing measures regarding their health via a computerised method.

To self-report health-outcomes, children must have at least a rudimentary self-concept and ability to express this, understand the basic notions of health and illness, be able to pay attention, discriminate between the response options, recall health experiences and write a response [92]. Until 4–5 years old, children’s language and thought processes are limited, so their ability to go through these process is also limited [101]. Children as young as 3 years of age were included in some of the studies in this review but results were presented alongside those of children ranging from 6 to 17 years old. The results of this review suggest that most children over five are able to reliably self-report on their health to some degree, with children younger than this exhibiting a ‘yes’ bias in response to questions [45].

Response format

Up until 6–7 years old, children view themselves in predominantly physical terms and their response to questionnaires is mainly dichotomous [102]. This is demonstrated in studies of 3–7-year-olds using a 3-point faces scale where only the anchors were used [26, 27]. Evidence on the ability of CYP over 7 years old to use 5- or 6-point response formats is mixed. This may be a reflection of variability in children’s development, with chronological age having less of an influence than cognitive ability [5]. Difficulty with the middle of scales was found in cognitive interview studies in those 5–18 years using Likert scales [42, 44, 92, 94]. In contrast, evidence from other cognitive interview and validity and reliability studies showed that those over 8 years old can understand 5-point Likert scales [20, 34, 42, 43, 46, 95] and that children over the age of 7 years can validly and reliably use scales with six faces [16, 33, 49, 93, 96]. However, item response theory studies show that the use of 5-point Likert scales led to disordered thresholds and 3-point scales functioned better in those 8–18 years old [17, 38, 60]. As data for all ages was usually presented together, it is not possible to ascertain whether older children can reliably use a 5-point response format. The VAS was less reliable and valid than Likert or faces across the age span [18, 57] and functions better with pictorial anchors [29]. There was an overwhelming preference at all ages for faces scales, with the VAS being the least preferred, suggesting that children are motivated by visually appealing response formats. It is recommended that when developing PROMS for CYP consideration is given to making them visually appealing to improve acceptability. It is also recommended that a dichotomous response format is used for those aged 5–7 years and a 3-point response format should be considered for those seven and over. Validity of response formats should not be evaluated solely in terms of convergent and discriminant validity of the measure, as this will often be high. Cognitive interview studies should also be undertaken, to give greater insight into how response format is understood. This review found no evidence that children who had underlying health conditions, were able to more reliably use any of the response formats described than their healthy peers.

Recall period

Evidence on recall period is limited, with only 11 studies reporting on this. These suggest that recall period should be kept to 24–48 h for those under 8 [92, 93]. Those over 8 years old are able to respond reliably to events that occur over the past 7–14 days [66, 67, 92, 95]. It is recommended that when developing PROMs for CYP the recall period is kept to no more than 48 h for those under 8 years. From 8 years old CYP seem to be able to recall the past 14 days, but due to data being presented for wide age ranges is unclear from what age CYP may be able to recall further than this.

Administration mode

Online and paper-and-pencil response formats demonstrated moderate to strong correlation [71, 75, 76, 81, 83, 84, 87,88,89, 91], similar to findings in adults [103] and there was an overwhelming preference for a computerised format [71,72,73, 78, 81, 87, 91]. Sensitive questions are more likely to be answered honestly in a computerised measure, probably as this method of data collection is perceived as more anonymous [70, 74, 78, 79]. There was fewer missing data on computerised versions of measures, possibly because children were not allowed to move to the next question if a response was left unanswered [75, 82, 85]. Those under 8 years old may need help from an adult to complete computerised outcome measures [96]. It is recommended that PROMS developed for CYP of all ages include a computerised version to enhance acceptability.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review provides evidence of children’s ability to self-report on their health outcomes in terms of recall period, response format and administration mode of measures but has some limitations. The inclusion criteria only incorporated articles published in the English language and searches were carried out in health-related databases; further evidence may be found in educational research. There were relatively few studies on recall period (n = 11) and the effects of cognitive ability rather than chronological age (n = 2) which highlight areas for future research. This review identified 13,215 articles for screening, another eight were included as a result of hand-searching and communication with experts. The assessment of recall period, response format and administration mode was a small part of these studies and as such, was not included in the paper keywords. The quality of included studies was poor in some instances which could have affected the reported results. These were included as it is often not possible to assess which aspects were addressed but not reported in the published paper. This is particularly relevant for older studies that were published before current reporting guidance was developed. Sample size was sometimes small, but it is well known that recruiting to paediatric research, particularly when this includes children with an underlying health condition, can be challenging [104]. A large number of studies were researching pain focused measures, rather than having a multi-dimensional focus.

Most included studies did not stratify their results by age, presenting data for wide age ranges. This makes it impossible to distinguish variation in ability by age group. As cognitive ability usually improves with age, it is recommended that when developing PROMs, psychometric testing is stratified by age and/or cognitive ability. PROM developers should also consider having different versions for different age groups or developmental ability to account for this. Future research could also take further steps to appraise the reliability of CYP self-report by using multi-indicator approaches, such as lack of response variability, excessive response variation and extreme, inconsistent or improbable response patterns, to assess invalid responses at the individual level [105].

Implications for developing PROMS for CYP.

From this systematic review we make eight recommendations for developing PROMS for CYP. These are:

-

1.

Proxy measures should be used for those under 5 years old.

-

2.

Measures should be visually appealing, to improve acceptability.

-

3.

PROM studies should be analysed and reported in developmentally appropriate age bands.

-

4.

Developers should consider different versions of a measure for different age groups.

-

5.

Development should include both cognitive interview studies, and psychometric testing to enhance understanding of how children formulate answers.

-

6.

5–7 years olds should be given a dichotomous response format; those 7 years and over should be given a three-point response format.

-

7.

Recall period should be kept short, no more than 48 h for those 5–7 years.

-

8.

PROMS should have a computerised version.

We propose that these recommendations are used alongside the COSMIN and Rothrock [14, 106] guidance on PROM development and validation.

Conclusion

Development of PROMS for CYP is complex and challenging due to diversity in developmental stage and cognitive ability. Children < 5 years old are unable to reliably report on their own health outcomes. Children < 8 years old cannot accurately recall beyond the past 48 h and can only reliably use a dichotomous response format. Children find visually appealing measures, in a computerised format more acceptable to use. Future work should focus on the impact of cognitive ability on self-report in CYP, reporting results of validation studies in smaller age ranges and establishing whether CYP with underlying health conditions are more able to report on their own health outcomes than their healthy peers. The results of this review have both clinical and research implications. They can be used to inform appropriate choice of PROM in the clinical setting. Our eight recommendations for developing PROMS for CYP can be used to further research in PROM development for CYP.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this review are available in the supplementary material.

References

Kingsley, C., & Patel, S. (2017). Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Education, 17(4), 137–144.

Antunes, B., Harding, R., Higginson, I. J., & EUROIMPACT. (2014). Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: A systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliative Medicine, 28(2), 158–175.

Quittner, A. L., Modi, A., & Cruz, I. (2008). Systematic review of health-related quality of life measures for children with respiratory conditions. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 9, 220–232.

Higginson, I. J., & Carr, A. J. (2001). Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ, 322(7297), 1297–1300.

Morris, C., Gibbons, E., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2009). Child and Parent reported outcome measures: A scoping report focusing on feasibility for routine use in the NHS. Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford.

Varni, J. W., Limbers, C. A., & Burwinkle, T. M. (2007). How young can children reliably and validly self-report their health-related quality of life? An analysis of 8,591 children across age subgroups with the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 1.

de Vet, H. C. W., Terwee, C. B., Mokkink, L. B., & Knol, D. L. (2011). Measurement in medicine. Cambridge University Press.

Bevans, K. B., Riley, A. W., Moon, J., & Forrest, C. B. (2010). Conceptual and methodological advances in child-reported outcomes measurement. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 10(4), 385–396.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Wille, N., Wetzel, R., Nickel, J., & Bullinger, M. (2006). Generic health related quality of life assessment in children and adolescents. Methodological considerations. PharmacoEconomics, 2006(24), 12.

Solans, M., Pane, S., Estrada, M. D., Serra-Sutton, V., Berra, S., Herdman, M., et al. (2008). Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: A systematic review of generic and disease-specific instruments. Value Health, 11(4), 742–764.

Eiser, C., & Morse, R. (2001). A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 84(3), 205–211.

Coombes, L. H., Wiseman, T., Lucas, G., Sangha, A., & Murtagh, F. E. (2016). Health-related quality-of-life outcome measures in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and feasibility of use. Palliative Medicine, 30(10), 935–949.

Mokkink, L. B., de Vet, H. C. W., Prinsen, C. A. C., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Bouter, L. M., et al. (2018). COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Quality of Life Research, 27(5), 1171–1179.

Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

Baxter, A. L., Watcha, M. F., Baxter, W. V., Leong, T., & Wyatt, M. M. (2011). Development and validation of a pictorial nausea rating scale for children. Pediatrics, 127(6), e1542-1549.

Benson, P. E., Cunningham, S. J., Shah, N., Gilchrist, F., Baker, S. R., Hodges, S. J., et al. (2016). Development of the Malocclusion Impact Questionnaire (MIQ) to measure the oral health-related quality of life of young people with malocclusion: part 2—Cross-sectional validation. Journal of Orthodontics, 43(1), 14–23.

Berntson, L., & Svensson, E. (2001). Pain assessment in children with juvenile chronic arthritis: A matter of scaling and rater. Acta Paediatrica, 90(10), 1131–1136.

Borgers, N., Hox, J., & Sikkel, D. (2003). Response quality in survey research with children and adolescents: The effect of labeled response options and vague quantifiers. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 15(1), 83–94.

Borgers, N., Hox, J., & Sikkel, D. (2004). Response effects in surveys on children and adolescents: The effect of number of response options, negative wording, and neutral mid-point. Quality & Quantity, 38(1), 17–33.

Campbell, W. N., & Skarakis-Doyle, E. (2011). Innovations in measuring peer conflict resolution knowledge in children with LI: Exploring the accessibility of a visual analogue rating scale. Journal of Communication Disorders, 44(2), 207–217.

Castarlenas, E., Miró, J., & Sánchez-Rodríguez, E. (2013). Is the verbal numerical rating scale a valid tool for assessing pain intensity in children below 8 years of age? Journal of Pain, 14(3), 297–304.

Chambers, C. T., & Craig, K. D. (1998). An intrusive impact of anchors in children’s faces pain scales. Pain, 78(1), 27–37.

Chambers, C. T., Giesbrecht, K., Craig, K. D., Bennett, S. M., & Huntsman, E. (1999). A comparison of faces scales for the measurement of pediatric pain: Children’s and parents’ ratings. Pain, 83(1), 25–35.

Chambers, C. T., Hardial, J., Craig, K. D., Court, C., & Montgomery, C. (2005). Faces scales for the measurement of postoperative pain intensity in children following minor surgery. Clinical Journal of Pain, 21(3), 277–285.

Decruynaere, C., Thonnard, J. L., & Plaghki, L. (2009). How many response levels do children distinguish on faces scales for pain assessment? European Journal of Pain, 13(6), 641–648.

Emmott, A. S., West, N., Zhou, G., Dunsmuir, D., Montgomery, C. J., Lauder, G. R., et al. (2017). Validity of simplified versus standard self-report measures of pain intensity in preschool-aged children undergoing venipuncture. Journal of Pain, 18(5), 564–573.

Fanciullo, G. J., Cravero, J. P., Mudge, B. O., McHugo, G. J., & Baird, J. C. (2007). Development of a new computer method to assess children’s pain. Pain Medicine, 8(Suppl 3), S121-128.

Fritz, G., Spirito, A., Yeung, A., Klein, R., & Freedman, E. (1994). A pictorial visual analog scale for rating severity of childhood asthma episodes. Journal of Asthma, 31(6), 473–478.

Gharaibeh, M., & Abu-Saad, H. (2002). Cultural validation of pediatric pain assessment tools: Jordanian perspective. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13(1), 12–18.

Goodenough, B., Addicoat, L., Champion, G. D., McInerney, M., Young, B., Juniper, K., et al. (1997). Pain in 4- to 6-year-old children receiving intramuscular injections: A comparison of the Faces Pain Scale with other self-report and behavioral measures. Clinical Journal of Pain, 13(1), 60–73.

Hicks, C. L., von Baeyer, C. L., Spafford, P. A., van Korlaar, I., & Goodenough, B. (2001). The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain, 93(2), 173–183.

Hunter, M., McDowell, L., Hennessy, R., & Cassey, J. (2000). An evaluation of the Faces Pain Scale with young children. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management, 20(2), 122–129.

Joffer, J., Jerdén, L., Öhman, A., & Flacking, R. (2016). Exploring self-rated health among adolescents: A think-aloud study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–10.

Jung, J. H., Lee, J. H., Kim, D. K., Jung, J. Y., Chang, I., Kwon, H., et al. (2018). Validation of the “Pain Block” concrete ordinal scale for children aged 4 to 7 years. Pain, 159(4), 656–662.

Keck, J. F., Gerkensmeyer, J. E., Joyce, B. A., & Schade, J. G. (1996). Reliability and validity of the Faces and Word Descriptor Scales to measure procedural pain. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 11(6), 368–374.

Lawford, J., Volavka, N., & Eiser, C. (2001). A generic measure of Quality of Life for children aged 3–8 years: Results of two preliminary studies. Pediatric Rehabilitation, 4(4), 197–207.

Leske, D. A., Holmes, J. M., Melia, B. M., & Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. (2015). Evaluation of the Intermittent Exotropia Questionnaire using Rasch analysis. JAMA Ophthalmology, 133(4), 461–465.

Locker, D., Jokovic, A., & Allison, P. (2007). Direction of wording and responses to items in oral health-related quality of life questionnaires for children and their parents. Community Dentistry & Oral Epidemiology, 35(4), 255–262.

Maïano, C., Bégarie, J., Morin, A. J. S., & Ninot, G. (2009). Assessment of physical self-concept in adolescents with intellectual disability: Content and factor validity of the Very Short Form of the Physical Self-Inventory. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 39(5), 775–787.

Miro, J., & Huguet, A. (2004). Evaluation of reliability, validity, and preference for a pediatric pain intensity scale: The Catalan version of the faces pain scale–revised. Pain, 111(1–2), 59–64.

Morley, T. E., Cataudella, D., Fernandez, C. V., Sung, L., Johnston, D. L., Nesin, A., et al. (2014). Development of the Pediatric Advanced Care Quality of Life Scale (PAC-QoL): Evaluating comprehension of items and response options. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 61(10), 1835–1839.

O’Sullivan, C., Dupuis, L. L., Gibson, P., Johnston, D. L., Baggott, C., Portwine, C., et al. (2014). Refinement of the symptom screening in pediatrics tool (SSPedi). British Journal of Cancer, 111(7), 1262–1268.

Ogden, C. A., Abbott, J., Aggett, P., Derkx, B. H., Maity, S., Thomas, A. G., et al. (2008). Pilot evaluation of an instrument to measure quality of life in British children with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition, 46(1), 117–120.

Okanda, M., & Itakura, S. (2010). When do children exhibit a “yes” bias? Child Development, 81(2), 568–580.

Ortqvist, M., Roos, E. M., Brostrom, E. W., Janarv, P. M., & Iversen, M. D. (2012). Development of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for children (KOOS-Child): Comprehensibility and content validity. Acta Orthopaedica, 83(6), 666–673.

Shields, B. J., Palermo, T. M., Powers, J. D., Grewe, S. D., & Smith, G. A. (2003). Predictors of a child’s ability to use a visual analogue scale. Child: Care, Health & Development, 29(4), 281–290.

Shields, B. J., Palermo, T. M., Powers, J. D., Fernandez, S. A., & Smith, G. A. (2005). The role of developmental and contextual factors in predicting children’s use of a visual analogue scale. Children’s Health Care, 34(4), 273–287.

Stanford, E. A., Chambers, C. T., & Craig, K. D. (2006). The role of developmental factors in predicting young children’s use of a self-report scale for pain. Pain, 120(1–2), 16–23.

Staphorst, M. S., Timman, R., Passchier, J., Busschbach, J. J. V., van Goudoever, J. B., & Hunfeld, J. A. M. (2017). The development of the DISCO-RC for measuring children’s discomfort during research procedures. BMC Pediatrics, 17(1), 199.

Tesler, M. D., Savedra, M. C., Holzemer, W. L., Wilkie, D. J., Ward, J. A., & Paul, S. M. (1991). The word-graphic rating scale as a measure of children’s and adolescents’ pain intensity. Research in Nursing & Health, 14(5), 361–371.

von Baeyer, C. L., Chambers, C. T., Forsyth, S. J., Eisen, S., & Parker, J. A. (2013). Developmental data supporting simplification of self-report pain scales for preschool-age children. Journal of Pain, 14(10), 1116–1121.

Watson, K., Baranowski, T., & Thompson, D. (2006). Item response modeling: An evaluation of the children’s fruit and vegetable self-efficacy questionnaire. Health Education Research, 21(Suppl 1), i47-57.

West, N., Oakes, L., Hinds, P. S., Sanders, L., Holden, R., Williams, S., et al. (1994). Measuring pain in pediatric oncology ICU patients…including commentary by Wong DL. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 11(2), 64–70.

McGrath, P. A., Seifert, C. E., Speechley, K. N., Booth, J. C., Stitt, L., & Gibson, M. C. (1996). A new analogue scale for assessing children’s pain: An initial validation study. Pain, 64(3), 435–443.

Pagé, M. G., Katz, J., Stinson, J., Isaac, L., Martin-Pichora, A. L., & Campbell, F. (2012). Validation of the numerical rating scale for pain intensity and unpleasantness in pediatric acute postoperative pain: Sensitivity to change over time. Journal of Pain, 13(4), 359–369.

Luffy, R., & Grove, S. K. (2003). Examining the validity, reliability, and preference of three pediatric pain measurement tools in African-American children. Pediatric Nursing, 29(1), 54–59.

Gulur, P., Rodi, S. W., Washington, T. A., Cravero, J. P., Fanciullo, G. J., McHugo, G. J., et al. (2009). Computer Face Scale for measuring pediatric pain and mood. Journal of Pain, 10(2), 173–179.

van Laerhoven, H., van der Zaag-Loonen, H. J., & Derkx, B. H. (2004). A comparison of Likert scale and visual analogue scales as response options in children’s questionnaires. Acta Paediatrica, 93(6), 830–835.

Klassen, A., Grant, C., Barr, R., Brill, H., de Camargo, O., Ronen, G., et al. (2015). Development and validation of a generic scale for use in transition programmes to measure self-management skills in adolescents with chronic health conditions: The TRANSITION-Q. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(4), 547–558.

Chogle, A., Sztainberg, M., Bass, L., Youssef, N. N., Miranda, A., Nurko, S., et al. (2012). Accuracy of pain recall in children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition, 55(3), 288–291.

Heyer, G. L., Perkins, S. Q., Rose, S. C., Aylward, S. C., & Lee, J. M. (2014). Comparing patient and parent recall of 90-day and 30-day migraine disability using elements of the PedMIDAS and an Internet headache diary. Cephalalgia, 34(4), 298–306.

Okupa, A. Y., Sorkness, C. A., Mauger, D. T., Jackson, D. J., Lemanske, R. F., & Lemanske, R. F., Jr. (2013). Daily diaries vs retrospective questionnaires to assess asthma control and therapeutic responses in asthma clinical trials: Is participant burden worth the effort? Chest, 143(4), 993–999.

Self, M. M., Williams, A. E., Czyzewski, D. I., Weidler, E. M., & Shulman, R. J. (2015). Agreement between prospective diary data and retrospective questionnaire report of abdominal pain and stooling symptoms in children with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 27(8), 1110–1119.

van den Brink, M., Bandell-Hoekstra, E. N., & Abu-Saad, H. H. (2001). The occurrence of recall bias in pediatric headache: A comparison of questionnaire and diary data. Headache, 41(1), 11–20.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Devine, J., Bevans, K., Riley, A. W., Moon, J., Salsman, J. M., et al. (2014). Subjective well-being measures for children were developed within the PROMIS project: Presentation of first results. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(2), 207–218.

Jacobson, C. J., Jr., Kashikar-Zuck, S., Farrell, J., Barnett, K., Goldschneider, K., Dampier, C., et al. (2015). Qualitative evaluation of pediatric pain behavior, quality, and intensity item candidates and the PROMIS pain domain framework in children with chronic pain. The Journal of Pain, 16(12), 1243–1255.

Bender, B. G., Bartlett, S. J., Rand, C. S., Turner, C., Wamboldt, F. S., & Zhang, L. (2007). Impact of interview mode on accuracy of child and parent report of adherence with asthma-controller medication. Pediatrics, 120(3), e471-477.

Castarlenas, E., Sanchez-Rodriguez, E., de la Vega, R., Roset, R., & Miro, J. (2015). Agreement between verbal and electronic versions of the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS-11) when used to assess pain intensity in adolescents. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 31(3), 229–234.

Fouladi, R. T., Rew, L., & Horner, S. D. (2006). Comparison of three modes of measuring stress, coping, and humor in school-age children. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 14(2), 79–98.

Geerdink, L. M., Prince, F. H., Looman, C. W., & van Suijlekom-Smit, L. W. (2009). Development of a digital Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire for systematic monitoring of disease activity in daily practice. Rheumatology (Oxford), 48(8), 958–963.

Jensen, H. I., Ammentorp, J., Kofoed, P. E., Jensen, H. I., Ammentorp, J., & Kofoed, P.-E. (2010). Assessment of health care by children and adolescents depends on when they respond to the questionnaire. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 22(4), 259–265.

Jones, L. M., & Buchanan, H. (2010). Assessing children’s dental anxiety in New Zealand. New Zealand Dental Journal, 106(4), 132–136.

Knight, J. R., Harris, S. K., Sherritt, L., Van Hook, S., Lawrence, N., Brooks, T., et al. (2007). Adolescents’ preference for substance abuse screening in primary care practice. Substance Abuse, 28(4), 107–117.

Lloyd, K. (2011). Kids’ Life and Times: Using an Internet survey to measure children’s health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 20(1), 37–44.

Mangunkusumo, R. T., Moorman, P. W., Van Den Berg-de Ruiter, A. E., Van Der Lei, J., De Koning, H. J., & Raat, H. (2005). Internet-administered adolescent health questionnaires compared with a paper version in a randomized study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36(1), 70.e71-76.

Mangunkusumo, R. T., Duisterhout, J. S., de Graaff, N., Maarsingh, E. J., de Koning, H. J., & Raat, H. (2006). Internet versus paper mode of health and health behavior questionnaires in elementary schools: Asthma and fruit as examples. Journal of School Health, 76(2), 80–86.

Mauz, E., Hoffmann, R., Houben, R., Krause, L., Kamtsiuris, P., & Goswald, A. (2018). Mode equivalence of health indicators between data collection modes and mixed-mode survey designs in population-based health interview surveys for children and adolescents: Methodological study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(3), e64.

McCabe, S. E., Boyd, C. J., Young, A., Crawford, S., & Pope, D. (2005). Mode effects for collecting alcohol and tobacco data among 3rd and 4th grade students: A randomized pilot study of Web-form versus paper-form surveys. Addictive Behaviors, 30(4), 663–671.

Moskowitz, J. M. (2004). Assessment of cigarette smoking and smoking susceptibility among youth: Telephone computer-assisted self-interviews versus computer-assisted telephone interviews. Public Opinion Quarterly, 68(4), 565–587.

Nitikman, M., Mulpuri, K., & Reilly, C. W. (2017). Internet-administered health-related quality of life questionnaires compared with pen and paper in an adolescent scoliosis population: A randomized crossover study. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics, 37(2), e75–e79.

Raat, H., Mangunkusumo, R. T., Landgraf, J. M., Kloek, G., & Brug, J. (2007). Feasibility, reliability, and validity of adolescent health status measurement by the Child Health Questionnaire Child Form (CHQ-CF): Internet administration compared with the standard paper version. Quality of Life Research, 16(4), 675–685.

Raat, H., Mangunkusumo, R. T., Mohangoo, A. D., Juniper, E. F., & Van Der Lei, J. (2007). Internet and written respiratory questionnaires yield equivalent results for adolescents. Pediatric Pulmonology, 42(4), 357–361.

Robles, N., Rajmil, L., Rodriguez-Arjona, D., Azuara, M., Codina, F., Raat, H., et al. (2015). Development of the web-based Spanish and Catalan versions of the Euroqol 5D-Y (EQ-5D-Y) and comparison of results with the paper version. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes, 13, 72.

Trapl, E. S., Taylor, H. G., Colabianchi, N., Litaker, D., & Borawski, E. A. (2013). Value of audio-enhanced handheld computers over paper surveys with adolescents. American Journal of Health Behavior, 37(1), 62–69.

Varni, J. W., Limbers, C. A., & Newman, D. A. (2009). Using factor analysis to confirm the validity of children’s self-reported health-related quality of life across different modes of administration. Clinical Trials, 6(2), 185–195.

Wood, C., von Baeyer, C. L., Falinower, S., Moyse, D., Annequin, D., & Legout, V. (2011). Electronic and paper versions of a faces pain intensity scale: Concordance and preference in hospitalized children. BMC Pediatrics, 11, 87.

Young, N. L., Varni, J. W., Snider, L., McCormick, A., Sawatzky, B., Scott, M., et al. (2009). The Internet is valid and reliable for child-report: An example using the Activities Scale for Kids (ASK) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(3), 314–320.

Eaton, D. K., Brener, N. D., Kann, L., Denniston, M. M., McManus, T., Kyle, T. M., et al. (2010). Comparison of paper-and-pencil versus Web administration of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS): Risk behavior prevalence estimates. Evaluation Review, 34(2), 137–153.

Magnus, B., Liu, Y., He, J., Quinn, H., Thissen, D., Gross, H., et al. (2016). Mode effects between computer self-administration and telephone interviewer-administration of the PROMIS® pediatric measures, self- and proxy report. Quality of Life Research, 25(7), 1655–1665.

Sun, T., West, N., Ansermino, J. M., Montgomery, C. J., Myers, D., Dunsmuir, D., et al. (2015). A smartphone version of the Faces Pain Scale-Revised and the Color Analog Scale for postoperative pain assessment in children. Pediatric Anesthesia, 25(12), 1264–1273.

Rebok, G., Riley, A., Forrest, C., Starfield, B., Green, B., Robertson, J., et al. (2001). Elementary school-aged children’s reports of their health: A cognitive interviewing study. Quality of Life Research, 10(1), 59–70.

Tomlinson, D., Hyslop, S., Stein, E., Spiegler, B., Vettese, E., Kuczynski, S., et al. (2019). Development of mini-SSPedi for children 4–7 years of age receiving cancer treatments. BMC Cancer, 19(1), 1–9.

Vreeman, R. C., Nyandiko, W. M., Ayaya, S. O., Walumbe, E. G., & Inui, T. S. (2014). Cognitive interviewing for cross-cultural adaptation of pediatric antiretroviral therapy adherence measurement items. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(1), 186–196.

Irwin, D. E., Varni, J. W., Yeatts, K., & DeWalt, D. A. (2009). Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: A patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) study. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes, 7, 3.

Gupta, N., Naegeli, A. N., Turner-Bowker, D. M., Flood, E. M., Heath, L. E., Mays, S. M., et al. (2016). Cognitive testing of an electronic version of the faces pain scale-revised with pediatric and adolescent sickle cell patients. The Patient: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, 9(5), 433–443.

Streiner, D. L., Norman, G. R., & Cairney, J. (2015). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford University Press.

Wong, D. L., & Baker, C. M. (1988). Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales. Pediatric Nursing, 14(1), 9–17.

Bieri, D., Reeve, R. A., Champion, G. D., Addicoat, L., & Ziegler, J. B. (1990). The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: Development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain, 41(2), 139–150.

Medical Research Council. (2009). Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): Identifying UK research priorites. Medical Research Council.

Borgers, N., De Leeuw, E. D., & Hox, J. (2000). Children as respondents in survey research: Cognitive development and response quality. Bulletin de Methodologie Sociologique, 66, 60–75.

De Civita, M., Regier, D., Alamgir, A. H., Anis, A. H., Fitzgerald, M. J., & Marra, C. A. (2005). Evaluating health-related quality-of-life studies in paediatric populations: Some conceptual, methodological and developmental considerations and recent applications. PharmacoEconomics, 23(7), 659–685.

Duracinsky, M., Lalanne, C., Goujard, C., Herrmann, S., Cheung-Lung, C., Brosseau, J. P., et al. (2014). Electronic versus paper-based assessment of health-related quality of life specific to HIV disease: Reliability study of the PROQOL-HIV questionnaire. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(4), e115.

Hudson, B. F., Oostendorp, L. J., Candy, B., Vickerstaff, V., Jones, L., Lakhanpaul, M., et al. (2017). The under reporting of recruitment strategies in research with children with life-threatening illnesses: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 31(5), 419–436.

Bevans, K. B., Ahuvia, I. L., Hallock, T. M., Mendonca, R., Roth, S., Forrest, C. B., et al. (2020). Investigating child self-report capacity: A systematic review and utility analysis. Quality of Life Research, 29(5), 1147–1158.

Rothrock, N. E., Kaiser, K. A., & Cella, D. (2011). Developing a valid patient-reported outcome measure. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 90(5), 737–742.

Acknowledgements

We thank the European Research Council for the financial support needed to undertake this study. The Children’s Palliative care Outcome Scale (CPOS) Study Steering Group members are: Anna-Karenia Anderson, Lydia Bates, Debbie Braybrook, Rachel Burman, Alan Craft, Finella Craig, Julia Downing, Sara Fovargue, Bobbie Farsides, Lorna Fraser, Ann Goldman, Jane Green, Ping Guo, Richard Harding, Irene Higginson, Michelle Hills, Gill Hughes, Joanna Laddie, Angela Logun, Steve Marshall, Linda Maynard, Renee McCulloch, Eve Namisango, Susan Picton, Anna Roach, Gao Wei.

Funding

CPOS was funded by the European Research Council’s Horizon 2020 programme [Grant ID: 772635] with the overall aim to develop and validate a person-centered outcome measure for children, young people and their families affected by life-limiting & life-threatening condition. Principal Investigator: Richard Harding. This article reflects only the author’s views and the European Research Council is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Coombes, L., Bristowe, K., Ellis-Smith, C. et al. Enhancing validity, reliability and participation in self-reported health outcome measurement for children and young people: a systematic review of recall period, response scale format, and administration modality. Qual Life Res 30, 1803–1832 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02814-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02814-4