Abstract

Purpose

The Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit for informal carers (ASCOT-Carer) can be used to assess long-term care-related quality of life (LTC-QoL) of adult informal carers of persons using LTC services. The ASCOT-Carer instrument has been translated into several languages, but preference weights reflecting the relative importance of different outcome states are only available for England so far. In this paper, we estimated preference weights for the German version of the ASCOT-Carer for Austria and investigated the value people place on different QoL-outcome states.

Methods

We used data from a best–worst scaling (BWS) experiment and estimated a scale-adjusted multinomial logit (S-MNL) model to elicit preference weights for the ASCOT-Carer domain-levels. Data were collected using an online survey of the Austrian general population (n = 1001).

Results

Top levels in the domains of ‘Space and time to be yourself’, ‘Occupation’ and ‘Control over daily life’ were perceived as providing the highest utility, and states with high needs in the same domains seen as particularly undesirable. ‘Personal safety’ was the only domain where levels were roughly equidistant. In all other domains, the difference between the top two levels (‘ideal state’ and ‘no needs’) was very small.

Conclusion

The paper provides preference weights for the German version of ASCOT-Carer to be used in Austrian populations. Furthermore, the results give insight into which LTC-QoL-outcomes are seen as particularly (un)desirable, and may therefore help to better tailor services directed at informal carers and the persons they care for.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Informal care (care and support provided by relatives or non-kin) is a major resource in enabling people with long-term care (LTC) needs to age in place [1]. Informal care, however, is not available for free; it comes with indirect costs [2], on, for example, informal carers’ health [3], well-being [4] and employment opportunities [5], and direct costs, such as their time and resources spent providing care [6]. In aging societies, limiting direct and indirect costs on family and non-kin carers and improving their health and quality of life (QoL) is key for LTC policy to ensure the long-run availability of informal care. In line with this, European countries, having recognised the role of informal carers and the impact of the caring role on their lives, have started to set up support systems to assist caring of family members and, but less commonly, of non-kin [7].

LTC policies differ in their logic for providing support to informal carers depending on whether providing care for care-dependent adults is considered a public responsibility or mainly delegated to family members, leading to different service types and arrangements [8]. Traditionally, the Austrian LTC system has relied heavily on the availability and provision of informal care. Benefits and services for care-dependent people also aim implicitly to reduce care burden. More recently, efforts have been increased to target support directly at informal carers; however, take-up is generally low [9]. In order to support Austrian informal carers in their caring roles, a more in-depth understanding of both the QoL-impact of publicly supported services and the desirability or preference of certain carer-relevant QoL-outcomes is needed.

A variety of instruments have been developed to measure carers’ living conditions and QoL, such as the Carer Experience Scale (CES) [10], the Adult Carers Quality of Life questionnaire (AC-QoL) [11] and the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) [12]. These instruments have contributed to better understand living conditions of informal carers but they do not directly capture the effects of service provision on informal carers’ QoL, nor do they account for the value of QoL-states. Such preference-weighted measures are mainly found for health-related QoL (e.g. EQ-5D [13] and Health Utility Indexes (HUI 2 and 3) [14]), for more general well-being (Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB) [15]), and for QoL-impact of informal care (CarerQoL-7D [16]). The Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit for informal Carers (ASCOT-Carer), however, directly measures QoL-effects of LTC-related services on informal carers’ QoL, irrespective of whether those services are provided to the person they care for or directly to the informal carer. The measure is preference-weighted, meaning it accounts for people’s value of different QoL-states when caring for a relative or friend. Understanding people’s preferences is particularly useful for economic evaluations aiming to better allocate scarce resources [17] as knowledge about the importance of different health or QoL-states enables the evaluation of trade-offs and improves decision-making [18].

The ASCOT-Carer instrument comprises seven QoL-domains (‘Occupation’, ‘Control over daily life’, ‘Looking after yourself (Self-Care)’, ‘Personal safety’, ‘Social participation and involvement’, ‘Space and time to be yourself’, ‘Feeling supported and encouraged’) with four outcome levels each (‘ideal state’, ‘no needs’, ‘some needs’, and ‘high needs’). Preference weights reflecting the relative importance of different outcomes in each of the domains allow for a more accurate representation of the total score [19].

The ASCOT-Carer was originally developed in England and has been translated into several languages, including German. The German version has been validated and shows good measurement properties [20]. So far, preference weights for the ASCOT-Carer instrument have been published only for England [21]. However, preferences may vary across countries due to institutional differences and different LTC systems [22,23,24]. In order for the ASCOT-Carer instrument to be used in evaluations in different target populations, country-specific preference weights are required to adequately reflect the relative importance of QoL-states in these countries.

This paper aims to provide preference weights for the German version of the ASCOT-Carer instrument for use in Austria, generated from a best–worst scaling (BWS) experiment, and to shed light on the relative importance of different ASCOT-Carer QoL-outcome-states. Using preference weights to calculate the ASCOT-Carer score, representing LTC-related QoL (LTC-QoL) for informal carers, enhances the informative content of the measure by better reflecting the actual value of the QoL-state in a domain. Through the elicitation of preference weights, we also identify areas in which unmet needs are seen as particularly bad and highlight QoL-states in areas of carers’ lives that are seen as particularly desirable.

Methods

Data collection using a best–worst experiment design

Methods to measure preferences comprise of rating, ranking and choice-based methods, with choice-based methods given priority [18]. Within choice-based methods, BWS provides a cognitively less challenging alternative to elicit preferences compared to discrete choice experiments (DCEs) [25]. BWS designs allow for the inclusion of a larger number of attributes or domains without creating tasks sets that are highly demanding, or requiring a very large sample size [26]. This makes them more feasible for use with the ASCOT-Carer instrument, which has 28 (7 × 4) domain-levels in total. BWS uses data generated from choice sets asking respondents to choose ‘best’ and ‘worst’ elements out of a list of items. Therefore, they also elicit additional information regarding least preferred options compared to a traditional DCE [27]. We used a ‘profile case’ (type 2) best–worst experiment [28] consisting of choice sets showing the seven attributes (ASCOT-Carer domains) at different levels. The profile case of BWS asks respondents to compare individual attribute-levels (instead of full profiles, as they would in a traditional DCE) [21].

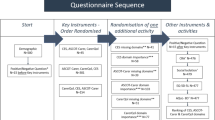

The experimental plan followed the approach employed for eliciting preference weights for the English ASCOT-Carer [21]. We used an orthogonal main effects plan (OMEP) to design the choice sets and a fractional-factorial design to reduce the full factorial (4^8 scenarios) to 32 scenarios. These were grouped into blocks of 8 and each respondent was randomly assigned to one of the blocks. To ensure that the respondents would understand the tasks and explanations in the survey, we performed pre-tests using cognitive interviews (think-aloud method) prior to the data collection.

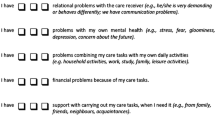

In the BWE experiment, respondents were asked to put themselves in the imaginary situation of being someone’s informal carer and presented with eight consecutive best–worst tasks. Each task was comprised of QoL-statements from the seven ASCOT-Carer domains (Fig. 1). In each task, respondents chose the ‘best’, ‘worst’, ‘second best’ and ‘second worst’ QoL-situations, meaning a total of 32 sequential choices. The positioning of the ASCOT-Carer domain-statements was randomised across individuals in order to prevent positioning effects from distorting preference weights for individual domain levels.

Illustration of a choice task (choice set) using the ASCOT-Carer domains. Note: Levels and ASCOT-Carer domain names were added for illustration and were not displayed in the survey (L1 = ideal state; L2 = no needs; L3 = some needs; L4 = high needs), the experiment used the German version of the ASCOT-Carer instrument; the Figure displays the wording of the original English instrument [29]

The BWS experiment was part of an online survey collecting sociodemographic characteristics, self-perceived health on a five-point scale, experience with care (including help or support provided in the last month), current QoL using the ASCOT-Carer instrument, and data on the understanding of the choice tasks.

A meta-analysis has found no significant differences between patient and general population preferences [30]. As a societal perspective is generally recommended for economic evaluations [31], a general population sample was used. Respondents were recruited via an online panel managed by Research Now (now Dynata). Data were collected in July and August 2016. The target sample size was 1000, with quotas for sex, age group and region (nine Austrian ‘Laender’) set to match national statistics.

Statistical analysis

The statistical model underlying BWS is based on the notion that the relative choice probabilities of items reflect their distance on the latent utility scale, and relative item utility can be inferred from these probabilities [25]. Austrian preference weights for the ASCOT-Carer instrument were obtained by using a scale-adjusted multinomial logit model (S-MNL). We estimated utilities for all domain-levels on a common scale, using the item with the lowest perceived utility as a reference point. We accounted for scale heterogeneity (differences in error variance between respondent groups [32]) as well as positioning effects (heterogeneity in choice probabilities related to the placement of the items in the list [21, 33]). As we did not aim to investigate differences in preferences in sub-groups, taste heterogeneity was not analysed in detail, but was used to correct for lack of sample representativeness. Following the approach by Burge, Potoglou, Kim, and Hess [34] and Huynh, Coast, Rose, Kinghorn, and Flynn [35], group-specific coefficients were weighted by applying the correct population proportions. The estimations were performed in Alogit (2017) and Biogeme [36], using robust sandwich estimators to account for the repeated nature of the tasks. For an in-depth description of the modelling approach and study design, see Batchelder et al. [21] and Hajji et al. [37].

Results

Sample descriptives

The sample comprised 1001 respondents. Persons with unrealistically short completion times for the BWS experiment (less than 4.5 min) were dropped during the data collection period and sampling was continued until the target number of 1000 respondents was reached. Tables 1 and 2 give an overview of the sample. Table 1 shows sample descriptives and corresponding national distributions. Sample characteristics defined by quotas (age, sex and region) mirror the national distributions. Persons with lower education were under-represented in the sample, as were lower income groups (deciles 1–5). Since deviations for both variables were by more than 10 percentage points, we accounted for this in the analysis.

Table 2 provides further details of the sample addressing health and care experiences. Overall, the self-assessed health status of the respondents was fairly good. Most respondents (68%) had a ‘very good’ or ‘good’ self-assessed health, only 1% of respondents listed their health as ‘very bad’. Most of the participants (60%) had had some prior experience with care (personal or through someone in their environment). When it comes to providing informal care, 20% of the respondents had stated they had provided informal help or support to someone in the month prior to the survey.

Results of the S-MNL model for Austria

Table 3 shows estimation results from the S-MNL model accounting for scale heterogeneity and positioning effects. Coefficients for all attribute-levels were estimated in reference to ‘Space and time to be yourself’ at level 4 (‘I don’t have any space or time to be myself’). Coefficients represent the relative values assigned to the QoL-states and decreased monotonically within each domain, with level 1 having the highest value and level 4 the lowest. This was the case for all domains except for ‘Feeling supported and encouraged’, where level 2 (‘I feel I have adequate encouragement and support’) was rated slightly, but not significantly, higher than level 1 (‘I feel I have the encouragement and support I want’), indicating that the two states were valued similarly. In order to account for this and maintain consistency, we estimated a joint coefficient for level 1 and level 2 in this domain.

All coefficients were significantly different from the reference category, indicating that all other ASCOT-Carer states are valued as having a higher utility than ‘Space and time to be yourself’ at level 4 (‘I don’t have any space or time to be myself’). In all domains, except for ‘Safety’, level 1 and 2 coefficients were not significantly different from each other at the 5% level. All other pairwise comparisons (i.e. comparisons between level 2 and 3 as well as between level 3 and 4) showed significant differences between the levels.

Coefficients for positioning effects for best choices were all negative, significantly different from the reference category (position 1, i.e. the uppermost item in the list) and increasing in magnitude. This indicates that the lower an item was in the list, the less likely it was to be picked as the ‘best’ choice compared to the uppermost item. No significant comparable effect was found for ‘worst’ choices, hence positioning coefficients for worst choices were not included in the final model.

We used scale heterogeneity analyses to correct for differences in error variance for respondent groups. Scale parameters are inversely related to the error variance and were set to 1 for the reference group in the model. Values higher than 1 indicated smaller error variance than the reference group and vice versa. Persons who had not understood the tasks at all or only understood the tasks sometimes showed higher error variance, as did respondents aged 35 and over and persons with faster completion times (minimum to quartile 1).

Preference weights for the ASCOT-Carer measure for Austria

To obtain the preference weights, coefficients from Table 3 were adjusted based on results from the taste heterogeneity analysis where needed, and rescaled so that the range of possible total ASCOT-Carer scores was between 0 and 1 [21].

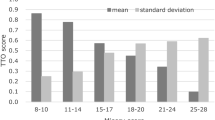

Figure 2 shows the final preference weights for the German ASCOT-Carer to be used in Austria. The highest rated QoL-state was ‘Occupation’ at level 1 (‘I’m able to spend my time as I want, doing things I value or enjoy’), followed by ‘Time and space to be yourself’ at level 1 (‘I have all the space and time I need to be myself’). Experiencing high needs (level 4) in the domain ‘Space and time to be yourself’ (‘I don’t have any space or time to be myself’) was perceived as most undesirable, followed by level 4 states in the domains ‘Occupation’ (‘I don’t do anything I value or enjoy with my time’) and ‘Control over daily life’ (‘I have no control over my daily life’).

Levels 1 (‘ideal state’) and 2 (‘no needs’) did not statistically differ, whereas there is a steep drop in perceived utility between levels 2 (‘no needs’) and 3 (‘some needs’) as well as between levels 3 (‘some needs’) and 4 (‘high needs’) for all domains except for ‘Personal safety’, where levels are roughly equidistant.

Discussion

Supporting informal carers has been recognised as key for sustainable care arrangements [40]. Thus, information on effects of service provision and preferences is relevant for designing carers’ support to positively impact on people’s lives and for comparing policy outcomes across countries.

This paper provided preference weights for the German version of the ASCOT-Carer instrument for use in Austria. The results suggest that increasing informal carers’ ability to have enough time for themselves, pursue meaningful activities and occupation, and have control over their lives should be the focus of interventions that aim to support informal carers of adult persons in Austria. For all seven QoL-domains, the results for Austria indicate that policies for informal carers who already experience high or some needs could make a substantial difference to their lives. Policies would be particularly valued for informal carers who lack sufficient or any opportunity to relax and ‘switch off’ from their caring role and responsibilities (as measured by the domain ‘Space and time to be yourself’). This analysis identified areas of life where unmet needs will be perceived as unacceptable by the Austrian population, as well as areas of life where ideal outcomes are seen as particularly desirable. Understanding people’s preferences thus enables LTC policymakers to better allocate scarce resources to target specific goals (e.g. improving carers’ control over their daily life) or groups of carers (e.g. persons with very little space and time for themselves).

As expected, preference weights decreased monotonically within domains from level 1 (‘ideal state’) to level 4 (‘high needs’), except for ‘Feeling supported and encouraged’, where level 1 and level 2 were estimated jointly. Differences between levels 1 (‘ideal state’) and 2 (‘no needs’) were small and usually not significant, indicating a noticeable drop in perceived utility only incurs past a certain point (differences are large when comparing an ‘OK’ (‘no needs’) state to a state with ‘some needs’, but not when comparing an ‘ideal state’ to an ‘OK’ state). The ‘Personal Safety’ domain was an exception in that all level-differences were significant and comparable in size, indicating that each decrease in LTC-QoL in this domain is noticeable.

In the English analysis of preference weights for the ASCOT-Carer, the highest-rated states were ‘Occupation’ at level 1 (same as Austria) and ‘Control over daily life’ at level 1 (4th highest in Austria). The lowest-rated states were ‘Control over daily life’ at level 4 (3rd lowest in Austria) and ‘Occupation’ at level 4 (same as Austria) [21]. An accurate and detailed country comparison of population-based preferences for QoL-states when caring for an older adult requires pooling of country data and poses an interesting path for future research in this area.

The study has some limitations. First, the analysis used an online panel, which by definition will not include groups with less access to the Internet. Second, we used quota sampling and adjusted for deviations in observed characteristics not captured by the quotas by weighting coefficients with the respective population proportions. Although quota sampling is widely used, as a non-probability sampling technique, it does not guarantee representativeness on unobserved characteristics. Since we were interested in correctly estimating the relative relationship between coefficients, we made adjustments where we found these relationships to differ for groups that were under-represented. However, as we cannot correct for unobserved characteristics or characteristics whose distribution in the target population is unknown. Furthermore, there is a debate about whether the S-MNL model is suited to disentangling different sources of heterogeneity in the choice data [41]. As the focus of the paper was not on heterogeneity, which was only controlled for in order to improve model fit and correct for the lack of sample representativeness, this should not impact upon the results. It should, however, be noted that further analyses looking into heterogeneity in more detail might benefit from alternative modelling approaches [42].

The preference weights for the ASCOT-Carer instrument presented here can be useful for studies investigating informal carers’ LTC-QoL and the impact of services on carers’ LTC-QoL in Austria. They allow for a more accurate representation of people’s service-related outcomes, given that outcome states in different QoL-domains are not always valued equally and levels within domains are not necessarily equidistant. The availability of preference weights makes the ASCOT-Carer instrument better suited for use in economic evaluations of service outcomes and helps to understand informal carers’ situations that are seen as particularly (un-)desirable. In addition, future research comparing preference weights obtained for different countries, e.g. preferences for Austria and England, could give insights into country-differences in the relative importance of QoL-states when caring for a family member or non-kin.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings cannot be made publicly available as data sharing is not covered by the informed consent.

References

OECD (2017) Health at a Glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2017-en.

Andersson, A., Levin, L. -Å., & Emtinger, B. G. (2002). The economic burden of informal care. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 18(1), 46–54.

McDaid, D. (2001). Estimating the costs of informal care for people with Alzheimer’s disease: Methodological and practical challenges. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(4), 400–405.

Chen, L., Fan, H., & Chu, L. (2019). The hidden cost of informal care: An empirical study on female caregivers’ subjective well-being. Social Science & Medicine, 224, 85–93.

Schneider, U., Trukeschitz, B., Mühlmann, R., & Ponocny, I. (2012). Do I Stay or Do I Go? Job change and labor market exit intentions of employees providing informal care to older adults. Health Economics, 22(10), 1230–1249. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2880.

Oliva-Moreno, J., Peña-Longobardo, L. M., García-Mochón, L., del Río Lozano, M., Metcalfe, I. M., & del Mar Garcia-Calvente, M. (2019). The economic value of time of informal care and its determinants (The CUIDARSE Study). PLoS ONE, 14(5), e0217016.

Courtin, E., Jemiai, N., & Mossialos, E. (2014). Mapping support policies for informal carers across the European Union. Health Policy, 118, 84–94.

Schneider, U., Sundström, G., Johannson, L., & Tortosa, M. Á. (2016). Policies to support informal care. In C. Gori, J.-L. Fernández, & R. Wittenberg (Eds.), Long-term care reforms in OECD countries: Successes and failures (pp. 219–244). Bristol: Policy Press.

Nagl-Cupal, M., Kolland, F., Zartler, U., Mayer, H., Bittner, M., Koller, M., et al. (2018). Angehörigenpflege in Österreich. Einsicht in die Situation pflegender Angehöriger und in die Entwicklung informeller Pflegenetzwerke. Bundesministerium für Arbeit, Soziales, Gesundheit und Konsumentenschutz: Universität Wien.

Al-Janabi, H., Flynn, T. N., & Coast, J. (2011). Estimation of a preference-based carer experience scale. Medical Decision Making, 31(3), 458–468.

Joseph, S., Becker, S., Elwick, H., & Silburn, R. J. M. H. R. J. (2012). Adult carers quality of life questionnaire (AC-QoL): Development of an evidence-based tool, Mental Health Review Journal, 17(2), 57–69.

Zarit, S. H., & Zarit, J. M. (1987). Instructions for the burden interview. University Park: Pennsylvania State University.

EuroQol Group. (1990). EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy, 16(3), 199–208.

Horsman, J., Furlong, W., Feeny, D., & Torrance, G. (2003). The Health Utilities Index (HUI): Concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1(54), 1–13.

Kaplan, R. M., Anderson, J. P., Wu, A. W., Mathews, W. C., Kozin, F., & Orenstein, D. (1989). The Quality of Well-being Scale: Applications in AIDS, cystic fibrosis, and arthritis. Medical Care, 27, S27–S43.

Hoefman, R., Exel, J., & Brouwer, W. (2013). Measuring the impact of caregiving on informal carers: A construct validation study of the CarerQol instrument. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11, 173.

Dolan, P., Olsen, J. A., Menzel, P., & Richardson, J. (2003). An inquiry into the different perspectives that can be used when eliciting preferences in health. Health Economics, 12(7), 545–551.

Mühlbacher, A. C., Kaczynski, A., Zweifel, P., & Johnson, F. R. (2016). Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best-worst scaling: An overview. Health Economics Review, 6(1), 2.

Lamu, A. N., Gamst-Klaussen, T., & Olsen, J. A. (2017). Preference weighting of health state values: What difference does it make, and why? Value in Health, 20(3), 451–457.

Trukeschitz, B., Hajji, A., Litschauer, J., Malley, J., Schoch, A., Rand, S., et al. (2020). Translation, cultural adaptation and construct validity of the German version of the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit for informal Carers (German ASCOT-Carer). Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02682-4.

Batchelder, L., Malley, J., Burge, P., Lu, H., Saloniki, E.-C., Linnosmaa, I., et al. (2019). Carer social care-related quality of life outcomes: Estimating English preference weights for the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit for Carers. Value in Health, 22(12), 1427–1440.

Badia, X., Roset, M., Herdman, M., & Kind, P. (2001). A comparison of United Kingdom and Spanish general population time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states. Medical Decision Making, 21(1), 7–16.

Heijink, R., Reitmeir, P., & Leidl, R. (2017). International comparison of experience-based health state values at the population level. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 138.

Janssen, M., Szende, A., Cabases, J., Ramos-Goñi, J. M., Vilagut, G., & König, H.-H. (2019). Population norms for the EQ-5D-3L: A cross-country analysis of population surveys for 20 countries. The European Journal of Health Economics, 20(2), 205–216.

Flynn, T. N., Louviere, J. J., Peters, T. J., & Coast, J. (2007). Best–worst scaling: What it can do for health care research and how to do it. Journal of Health Economics, 26(1), 171–189.

Witt, J., Scott, A., & Osborne, R. H. (2009). Designing choice experiments with many attributes. An application to setting priorities for orthopaedic waiting lists. Health Economics, 18(6), 681–696.

Cheung, K. L., Wijnen, B. F., Hollin, I. L., Janssen, E. M., Bridges, J. F., Evers, S. M., et al. (2016). Using best–worst scaling to investigate preferences in health care. Pharmacoeconomics, 34(12), 1195–1209.

Louviere, J. J., Flynn, T. N., & Marley, A. A. J. (2015). Best-worst scaling: Theory, methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rand, S. E., Malley, J. N., Netten, A. P., & Forder, J. E. (2015). Factor structure and construct validity of the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit for Carers (ASCOT-Carer). Quality of Life Research, 24(11), 2601–2614.

Dolders, M. G. T., Zeegers, M. P. A., Groot, W., & Ament, A. (2006). A meta-analysis demonstrates no significant differences between patient and population preferences. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 59(7), 653–664.

Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Torrance, G. W., O’Brien, B. J., & Stoddart, G. L. (2005). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davis, K. J., Burton, M., & Kragt, M. E. (2016). Discrete choice models: scale heterogeneity and why it matters (Working Paper 1602): School of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia.

Campbell, D., & Erdem, S. (2015). Position bias in best-worst scaling surveys: A case study on trust in institutions. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 97(2), 526–545.

Burge, P., Potoglou, D., Kim, W. C., & Hess, S. (2010). How do the public value different outcomes of social care?: RAND Europe Working Paper prepared for PSSRU and Office for National Statistics.

Huynh, E., Coast, J., Rose, J., Kinghorn, P., & Flynn, T. (2017). Values for the ICECAP-Supportive Care Measure (ICECAP-SCM) for use in economic evaluation at end of life. Social Science & Medicine, 189, 114–128.

Bierlaire, M. (2003). BIOGEME: A free package for the estimation of discrete choice models, TRANSP-OR-CONF-2006-048. URL: http://transp-or.epfl.ch/documents/proceedings/Bier03.pdf, http://www.strc.ch/Paper/bierlaire.pdf. Record created on 2008-02-15, modified on 2017-12-15.

Hajji, A., Trukeschitz, B., Malley, J., Batchelder, L., Saloniki, E., & Linnosmaa, I., et al. (2020). Population-based preference weights for the adult social outcomes toolkit (ASCOT) for service users for Austria: Findings from a best-worst experiment. Social Science and Medicine; 250, 112792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112792.112792.

Statistik Austria. (2016). Population by demographic characteristics from http://statistik.at/web_en/statistics/PeopleSociety/population/population_censuses_register_based_census_register_based_labour_market_statistics/population_by_demographic_characteristics/index.html.

Statistics Austria. (2014). Disposable household income in Austria using EU-SILC 2014, provided upon request by Statistics Austria.

Colombo, F., Llena-Nozal, A., Mercier, J., & Tjadens, F. (2011). Help wanted? Providing and paying for long-term care. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Hess, S., & Rose, J. M. (2012). Can scale and coefficient heterogeneity be separated in random coefficients models? Transportation, 39(6), 1225–1239.

Louviere, J. J. (2001). What if consumer experiments impact variances as well as means? Response variability as a behavioral phenomenon. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(3), 506–511.

Acknowledgements

We particularly thank Julien Forder (University of Kent, UK) for the acquisition of funding and general oversight of the EXCELC project and Peter Burge and Hui Lu (Rand Europe, UK) for their valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of the best–worst experiment. The authors would like to thank all participants for taking part in the current study, as well as Research Now (now Dynata), the organisation responsible for data collection.

Disclaimer

The data were collected using the German version of the ASCOT-Carer instrument. In this paper, the original English ASCOT-Carer measure is disclosed in full but ordinarily should not be used for any purposes without the appropriate permissions of the ASCOT team and the copyright holder—the University of Kent. Please visit www.pssru.ac.uk/ascot or email ascot@kent.ac.uk to enquire about permissions.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU). This publication reports on results of the EXCELC (Exploring Comparative Effectiveness and Efficiency of Long-term Care) project, which was funded by the NORFACE Welfare State Futures programme (Grant Number 462-14-160). In addition, the Austrian contribution to this project was co-funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (Project Number I 2252-G16) and the Vienna Social Fund (FSW - Fonds Soziales Wien). The views expressed are not necessarily those of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BT, AH, IL and JM contributed to the design of the data collection. BT conceived the paper and supervised translation of the experiment. AH and BT translated parts of the online experiment into German. BT, JM and IL supervised the data collection and analysis and were involved in acquired funding. AH and BT, interpreted the data with support of LB and JM. BT and AH drafted parts of the paper, revised the paper critically for important intellectual content at all stages. AH analysed the data with support of LB. LB and ES contributed to model creation and programming and revised the paper critically for important intellectual content. JM, LB, ES and IL revised the paper for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The responsible university office at the WU Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU Vice-Rector for Research) has determined that no ethics clearance is needed under university regulations.

Informed consent

All participants have provided written consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trukeschitz, B., Hajji, A., Batchelder, L. et al. What’s important when caring for a loved one? Population-based preference weights for the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit for informal carers (ASCOT-Carer) for Austria. Qual Life Res 30, 1975–1984 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02775-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02775-8